Полная версия

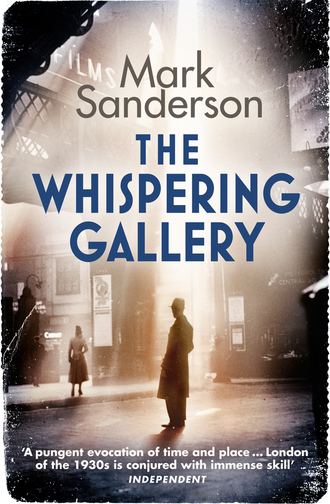

The Whispering Gallery

The Whispering Gallery

MARK SANDERSON

Dedication

To Miriam, without whom . . .

Epigraph

Let us be grateful to the mirror for revealing to us our appearance only.

Erewhon, Samuel Butler

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Foreword

Part One - Wardrobe Place

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Part Two - Dark House Lane

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Part Three - Sans Walk

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Bibliography

About the Author

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Foreword

It made no difference whether or not she opened her eyes. She was smothered in complete darkness. It was impossible to distinguish night from day.

How long had she been here? And where was here? It had to be somewhere underground. Her voice-box had cracked from screaming for the help that refused to come. She longed for the relief that unconsciousness lent her.

The chain attached to the tight spiked collar round her neck – What had he called it? A throat-catcher? – clanked as she tried once again to pull it off the bare brick wall. She was so thirsty she had resorted to licking the damp stone. The tip of her parched tongue was already torn. The collar prevented her getting any closer to the precious moisture.

She had broken all her nails – her lovely, long nails that she manicured daily – scratching in the search for a way out.

Hunger gnawed her insides. She was empty now: the stench of her piss and shit filled her nostrils. She could not stop shivering. The only thing in her favour was that it was July: had it been winter she would have already frozen to death.

She blushed at her nakedness and immediately reproached herself. What did it matter when she was about to die? And she had no doubt that she would soon be dead. He had told her as much on his last visit as he shortened the chain. Tears sprang to her eyes once more. She tried to catch them with her tongue. They felt shockingly hot on her cold, filthy skin.

The silence was shattered by the clang of a metal door. She shrank back into a corner and began to shake uncontrollably. A candle-flame pin-pricked the darkness. He was coming again. So far he had not touched her but he had made it quite plain what he eventually intended to do.

She screwed her eyes shut, terrified at what she might see. He would blindfold her and, to begin with, say nothing at all as he watched her for what seemed like hours. She could feel his eyes creeping over her flesh, lingering between her legs. It was only then that the whispering would begin.

Part One Wardrobe Place

Chapter One

Saturday, 3rd July 1937, 2.30 p.m.

He was going to take the plunge. It had been almost eight months now and he loved her more than any other girl in the world.

Even though the remorseless sun came slanting through the clear glass, it was cool in the vast interior of St Paul’s. Johnny, impatient as ever, strolled down the nave, dodged gawping tourists, and took a seat beneath the magnificent dome which, thanks to the exhibition in St Dunstan’s Chapel, he had already learned was actually three in one: the outer dome of fluted lead and stone that could be seen from all over London; a brick spire that held up the lantern at the very top of the cathedral; and, sixty feet below the outer one, an internal dome decorated with scenes from the life of St Paul in grisaille and gold. Biblical history had never been one of his strong suits – or interests – at school, but Johnny recognised the shipwreck on Malta, the conversion of the gaoler and the Ephesians burning books – just like the Nazis today. Nothing changed.

What little remained of his faith had been buried along with his mother after her early, excruciating, death from cancer. However, he was not in St Paul’s to pray but to propose marriage to Stella, the green-eyed, glossy-haired temptress he had met in The Cock, her father’s pub in Smithfield, back in December. They had been seeing more and more of each other since Christmas – and Johnny had been falling deeper and deeper in love. Although she still sometimes helped out behind the bar, Stella was now a fully qualified secretary who worked at C. Hoare & Co., a private bank in Fleet Street – which just happened to be a minute’s walk away from the Daily News where Johnny was a crime reporter.

Johnny checked that his mother’s engagement ring was still safely tucked in the inside pocket of his jacket – his father had died in the battle of Passchendaele when Johnny was three – and looked up to the Whispering Gallery where he intended to make his proposal. The acoustics were such that words whispered behind a hand travelled round the wall of the dome and into any ear pressed against the stone. There were only four people up there at present. One of them, a beanpole of a man, gaunt and unshaven, stood directly above the keystone of an arch decorated with a cherub behind a pair of crossed swords. He leaned over the ornate railings and watched those milling around a hundred feet below.

Johnny got to his feet. He was beginning to feel really nervous now. Stella wasn’t due for at least another ten minutes and she always made a point of being eight minutes late: “It makes you all the happier to see me.” She didn’t seem to understand that this was impossible.

“She can only say no,” said Matt, his oldest friend, in characteristically blunt fashion when Johnny had told him of his plans over several pints of Truman’s the night before. “But she’d be a fool if she did.”

Blunt, perhaps, but unswervingly loyal. Passing his sergeant’s exams had given Matt more than promotion in the ranks of the City of London Police; it had boosted his self-confidence – not that Johnny thought he needed any help in that department. Self-doubt was his own speciality.

He ambled through the quire – why the earlier spelling of choir was insisted upon was anybody’s guess – gazed at the dazzling blue and gold mosaics above him, passed the organ that would be bellowing out Old Hundredth the following morning, and turned right to face the windows where the unruly sun came streaming in. The funerary effigy of John Donne, the metaphysical poet who became Dean of St Paul’s in 1621, was now on his left. It was supernaturally realistic: every whisker of his beard, every crease of his shroud, stood out.

Johnny preferred prose to verse but he could still recall a few of the lines that Old Moggy had made them study, beating the rhythm with his wooden leg – supposedly made of mahogany, hence the teacher’s nickname. This, for example, from “The Anagram”:

Love built on beauty, soon as beauty, dies.

Stella would always be beautiful to him: even when she was sixty. Every time her almond eyes met his own his heart flipped. It seemed to liquefy and flood his body with euphoria. At such moments he felt he could do anything – and there was certainly nothing he wouldn’t do for her. The attraction wasn’t just physical – although he existed in a state of constant desire for her. He had never before made love to the same woman over such an extended period of time. His past was littered with a succession of brief but intense flings with actresses and dancers who had hoped he could help their careers by persuading colleagues to mention them in print. It still amazed him that sex with Stella got better and better, that the novelty did not wear off. She was his new-found land that he would never tire of exploring.

And yet he was equally happy simply doing nothing. It was enough just to be in her company. When they were together he felt complete. They made a handsome couple. They were the same height – five foot six; Johnny was accustomed to being looked down on – and shared other characteristics besides their startlingly green eyes: both were quick witted, with a fiery temper and a deep sense of fair play. However, Stella would not hesitate to knock him off his high horse when he was raging against social injustice.

It was not that she was in favour of inequality: she just couldn’t stand intellectual soppiness. Johnny had a tendency to get dewy-eyed about the plight of the underdog. Then again, he had seen a lot more than she had: more reality, more poverty and more death. Her protective father, a lumbering bear of a man who had no difficulty handling awkward customers, had done his best to shield her from the worst aspects of life in the capital. His possessiveness had ensured that they had yet to spend a whole night together. Johnny was not looking forward to asking him for permission to marry his daughter – if she said “yes”.

He hoped she wouldn’t make too much of a fuss about the 259 steps up to the gallery: a notice warned those wishing to ascend towards heaven that there were no stopping-off points on the way. It wasn’t as if he had chosen the Stone Gallery (378 steps) or even the Golden Gallery (530 steps).

On their second date they had climbed to the top of the Monument, the tallest isolated stone column in the world. Designed by Christopher Wren to commemor ate the Great Fire of London, which had started in Pudding Lane 202 feet away, it was consequently 202 feet high and contained 311 steps. When they had finally reached the iron cage at the top – built to prevent suicides – Johnny, checking no one was looking, had kissed her full, red lips and murmured, heart still pounding from the ascent: “You take my breath away.” Their laughter had hung between them in the frosty air.

He had felt on top of the world and wanted Stella to feel the same way. Together they had seen the City in a whole new light – a light enhanced and reflected by the flaming golden urn above them.

Johnny had made a point of going to places where neither of them had been before. The relationship was new territory for them both. Finally, in Postman’s Park, with its wall of plaques dedicated to local heroes, including Daniel Pemberton – foreman LSWR, surprised by a train when gauging the line, hurled his mate out of the track, saving his life at the cost of his own, Jan 17 1903 – Stella, fed up with all the talk of death, had said: “Next time, let’s go to the pictures like a normal couple.” The fact that she had referred to them as a “couple” had gone a long way towards mollifying him.

A love of the movies was another interest they shared. The death of Jean Harlow the month before had shocked them both. Hollywood’s first “sex goddess” was only twenty-six: four years younger than they were. Johnny had been mesmerised by her breasts the first time he had seen them burst out of the silver screen. He preferred her as a femme fatale in gangster flicks such as Beast of the City and Public Enemy rather than as a dizzy blonde in comedies like Hold Your Man and Wife versus Secretary. However, his reporter’s instincts were still intrigued by the echoes of Harlow’s personal life in Reckless.

The suicide of her on-screen husband Franchot Tone in the film recalled the death of Harlow’s second real-life husband Paul Bern, who was said to have shot himself in 1932. His apparent suicide note had a claim to being one of the worst ever:

Dearest dear. Unfortunately this is the only way to make good the frightful wrong I have done you and to wipe out my abject humiliation.

Paul.

You understand that last night was only a comedy.

What was more humiliating than being reduced to blowing out your brains? Yet the suicide rate had been climbing on both sides of the Atlantic throughout the decade. On the face of it Bern appeared to have had a lot to live for: he was both rich and respected. Even so the director had chosen to roll the end credits of his life story. Or had he? The men from MGM had been on the scene long before the cops or the coroner. What had the young Harlow seen in the much older, and reputedly impotent, man? She might have shot him herself in frustration. Johnny smelled a cover-up. One day he would write a book about it.

He had arranged to meet Stella in the middle of the sunburst on the floor beneath the centre of the dome. It was a visual representation of heaven on earth, a sign that Wren’s Masonic masterpiece was designed to unite the two. If Stella agreed to be his wife, the two of them would become one, and he would be in paradise. He stood 365 feet – one for each day of the year – beneath the golden cross that topped the dome. It didn’t seem a second since he and Stella had been laughing on top of the Monument – so much had happened since then. He glanced around yet again, hoping to spot her making her way towards him. No: as usual she was making him wait the full eight minutes.

Chapter Two

A woman screamed. A sickening crack echoed off the Portland stone. Tourists scattered across the black-and-white chequered marble. Johnny turned and, instinctively going against the flow of fleeing sightseers, moved closer to the centre of the action.

The jumper had fluked a soft landing but was surely dead. Black blood seeped from his head. Johnny knelt down and, using his fore and middle fingers, felt for a pulse behind the man’s ear. To his amazement, he detected a faint beat. He rolled him off the unfortunate clergyman he had landed on. It was too late: the corpulent priest resembled a beetle crushed by a callous schoolboy. He lay face down, his limbs and neck splayed at crazy angles. There was a hole in the sole of his left shoe.

Johnny, feeling nauseous, took a deep breath and exhaled slowly. If he had stood his ground for just a few seconds more it could have been him lying broken on the floor. Perhaps there was a god after all.

The suicide opened his eyes. The escaping blood had created a sticky halo round his head. His lips moved. Johnny bent down to hear what the beanpole was trying to say.

“I’m sorry. I . . .” His eyelids fluttered.

“What’s your name?” asked Johnny, already thinking of the piece he was going to write. He felt in vain for a pulse. The wretch was wearing a black suit of good quality. It was as if he had dressed up for the occasion. Johnny went through the man’s pockets. That was odd – they were completely empty. There was no wallet or loose change, no keys, not even a handkerchief.

“Can you believe it? He’s robbing the poor guy!” An American, flushed with indignation, pointed a pudgy finger at Johnny. The rubberneckers, reassured that it had not started raining men, had slowly gathered round to get a closer look. The circle tightened round him.

“Don’t be ridiculous. I’m trying to find out who he is. Why don’t you make yourself useful and go and find someone in authority?”

“There’s no need.” A middle-aged man in a dog collar gently cut through the crowd. Beady eyes took in the scene. They showed no sign of shock or grief. Countless funerals – in Britain and in France during the Great War – had inured him to death. “Please stand back.” He was plainly accustomed to being obeyed.

“Is he one of yours?” Johnny nodded at the flattened priest.

“And you are . . .?”

“John Steadman, Daily News.”

“Ah.” The gimlet eyes bore into him. “Mr Yapp was a member of our chapter. I presume he’s beyond our help?”

“Indeed. My deepest condolences.”

The clergyman searched for but could not detect a note of insincerity. “I’m Father Gillespie, Deacon of St Paul’s.”

“How d’you do.” They shook hands. Johnny reached into his pocket and flipped open the notebook with its miniature pencil held in a tiny leather loop. It went everywhere with him. “What were Mr Yapp’s Christian names?”

“Graham and Basil. He was proud to share his initials with Great Britain.”

“Thank you. I don’t suppose you know who the other man is? It seems he jumped from the Whispering Gallery.”

“He wouldn’t be the first to have done so.” The deacon sighed and lowered his voice. “And doubtless won’t be the last.” The eavesdroppers craned their necks. “Ladies and gentlemen, please stand back. This is a house of God, not a freak show.”

“The police will have to be informed.”

“The call is being made as we speak.”

Johnny was impressed. “That was quick.” It wouldn’t take long for the Snow Hill mob to get here. He handed Father Gillespie a business card. “May I telephone you later?”

“Of course. But what’s the hurry? You’re an eyewitness. The police will want to talk to you.”

“Actually, I’m not. I didn’t see the man jump. For all I know, he could have been pushed. However, by all means tell the cops I was here. They know where to find me.”

The ring of spectators that was growing by the minute reluctantly parted to let him through. Forgetting, once again, where they were, they broke into an excited chatter. A look of exasperation flitted across Gillespie’s face. Would he have to close the cathedral?

Johnny, using shorthand, scribbled down a few details while they were still fresh in his memory – the exact location of the bodies, the appearance of the two corpses, their time of death – before hurrying down the north aisle and out of the door by All Souls Chapel.

It was like standing in front of a blast furnace. He squinted in the sunshine, blinded for a moment, then hurried down the steps which in the dazzling light appeared to be nothing more than a series of black-and-white parallel lines. It was so hot even the pigeons had sought the shade.

Should he wait for Stella or run with the story? He only hesitated for a moment. She was not expecting him to propose so would not be particularly disappointed. Besides, it would serve her right for being late yet again. She would guess what had happened when she saw the bloody aftermath where they were supposed to have rendezvoused.

As he made his way down Ludgate Hill, overtaking red-faced shoppers, he slipped off his jacket and slung it over his arm. He took off his hat and loosened his tie. It made little difference. Sweat trickled down his spine, made his shirt stick to the small of his back. He licked his top lip. He was glad the office was only five minutes away. He could see it in the distance, shimmering in the haze.

The newsroom was a sauna even though all the third-floor windows were flung wide open. The roar of traffic competed with the constant trilling of telephones and the machine-gun tat-a-tat of typewriters. Fans whirred uselessly on every desk. Any unanchored piece of paper would be sent waltzing to the floor. The sweet smell of ink from the presses on the ground floor and dozens of lit cigarettes failed to mask the odour of unwashed armpits.

Johnny checked his pigeonhole for any post, memos or telephone messages. There were several slips from the Hello Girls on the ground floor and two envelopes. Before he could open either of them, Gustav Patsel, the news editor, came waddling up to him.

“It is your day off, no? What are you doing here?”

Rumours that Patsel was going to jump ship – go to another newspaper, or goose-step back to his Fatherland – had so far proved annoyingly untrue. He made no secret of the fact that he disapproved of Johnny’s recent promotion from junior to fully fledged reporter, but hadn’t had the guts to say anything to the editor, Victor Stone. Like most bullies he had a yellow belly. Johnny’s previous position remained unfilled. The management, trying to slow the soaring overheads, had ordered a temporary freeze on recruitment.

“Pencil” – as Patsel was mockingly known – considered Johnny disrespectful. He could never tell when he was being serious or insubordinately facetious. However, Steadman was too good a journalist to sack. His exposé of corruption within the City of London Police the previous Christmas was still talked about. Patsel couldn’t afford to lose any more staff from the crime desk – Bill Fox had retired in March – and furthermore he didn’t want Johnny working for the competition.

“I’ve got a story and I guarantee you no one else has got it – yet. A man’s just committed suicide in St Paul’s.”

“So what? Cowards kill themselves every day.”

“Only someone who doesn’t understand depression and despair would say that,” said Johnny, bristling. He held up his hand to stop the inevitable torrent of spluttering denial. “There’s more: he took someone with him. When he jumped from the Whispering Gallery he landed on a priest.”

“Ha!” The single syllable expressed both laughter and relief. Patsel’s eyes glittered behind the round, wire-rimmed glasses. “So much for the power of the Saviour. Has he been identified?”

“I know who the priest was, but the jumper didn’t have anything on him except his clothes. No money, no note, no photograph.”

“How do you know this?”

“I was there. I went through his pockets.”

Patsel was impressed – but he wasn’t about to show it.

“What?” Johnny could tell his boss was itching to say something.

“It is not important. Okay. Give me three hundred words – and try to get a name for the suicide.”

Johnny nodded. He had an hour and a half to develop the lead into a proper story. The copy deadline for the final edition was 5 p.m. There was a sports extra on a Saturday so that most of the match results could be included. He flopped down into Bill’s old chair and tipped back as far as he could go, just as his mentor had. Fox had taught him a great deal – in and out of the office. Although Johnny had no intention of following in the footsteps of the venal but essentially good-hearted hack, he had taken his desk when he left. It was by a window – not that it offered much of a view beyond the rain-streaked sooty tiles and rusting drainpipes in the light well at the core of the building.

“Stood you up, did she?” Louis Dimeo, the paper’s sports reporter, had slipped into the vacant seat at the desk opposite, which used to be Johnny’s. A grin lit up his dark, Italian features. Johnny was handsome enough but Louis, who spent most of his spare time kicking a ball or kissing girls, was in a different league – as he never stopped reminding him.

“Who?”

“Seeing more than one woman, are we? Surely you haven’t taken a leaf out of my book? Stella, of course.” They sometimes had a drink together after work – always with other colleagues, never alone – but Louis was too concerned about his physique to sink more than a couple of pints.

“An exclusive fell into my lap. Well, almost.” His telephone started ringing. “Haven’t you got anything better to do?”

“It’s all under control. The stringers will soon be calling the copytakers.”

“Why aren’t you at a match?”