Полная версия

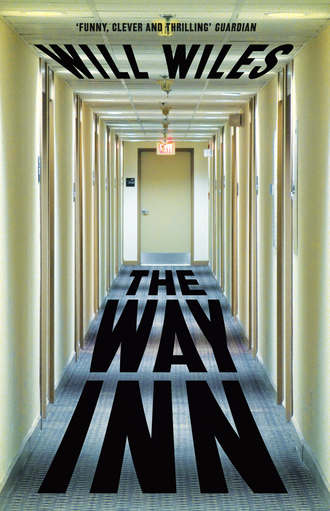

The Way Inn

‘Sure,’ she said. ‘I’d like that.’ Her mobile phone, briefly removed from the social mix, reappeared like a fluttering fan.

Boarding the bus, I felt heartened by the encounter. It wouldn’t be too difficult after all.

The bus filled quickly, but there was a further mysterious delay before it got moving. Still, it was warm and dry, and the throbbing engine was as soothing as the ocean. The air had a chemical bouquet – new, everything was new. I stared at the patterned moquette covering the seat in front of me. Blue and grey squares against another grey. Hidden messages, secret maps? No, just a computer-generated tessellation reiterating to infinity. People milling around outside. New tarmac. A woman sat in the seat next to mine; I appraised her with a half-glance and found little that interested me. She ignored me and thumbed her phone, her only resemblance to Rosa.

Movement. One of the organisers appeared at the front of the bus, craning her neck as if looking for someone among the passengers. The bus doors closed with a sigh; the organiser sat down. The engine changed its pitch and we moved off.

We drove along an access road parallel to the motorway. The motorway itself was hidden from view by a low ridge engineered to deaden the howl of the high-speed traffic. The beneficiaries of this landscaping were a row of chain hotels: the Way Inn behind us, ahead a Novotel, a Park Plaza and a Radisson Blu, all in the later stages of construction, surrounded by hoardings promising completion by the end of the year. Here was the delayed skywalk: an elegant glass-and-steel tube describing most of an arch over the access road, the ridge and the unseen motorway, but missing a central section, the exposed ends sutured with hazard-coloured plastic. On the Way Inn side of the road, the skywalk joined the beginnings of an enclosed pedestrian link between the hotels at the first-floor level. Eventually guests would be able to stroll to the MetaCentre in comfort, protected from the climate and the traffic, but only the Way Inn section was finished. Perhaps all this construction work was evidence of industry, investment, applied effort – but the scene was, as far as I could see, deserted. There were no other vehicles on the road.

Signs warned of an approaching junction and myriad available destinations. The bus circled the intersection, giving us a glimpse down on-ramps of the motorway beneath us, articulated lorries thundering through six lanes of filthy mist, and then of the old road, a petrol station’s bright obelisk, sheds, used cars. We didn’t take either of those routes. Instead the bus turned onto another access road, again parallel to the motorway, but on the opposite side. A vast object coalesced in the drizzle: eight immense white masts in two ranks of four suggesting the boundary of an area the size of a small town, high-tension steel crosshatching the air above. The MetaCentre. My first instinct was to laugh. For all its prodigious size and expense, and the giddying alignment of business and political interests it represented, there was something very basic about it. It was, in essence, a giant rectangular tent, with guy ropes strung from the masts supporting its roof, keeping the rain off the fair inside. Plus roads and parking. So there it was, the ace card for the economic planning of this whole region: a very big dry place that’s easy to get to. And easy to see – the white masts, as well as holding up the immense space-frame roof, were a landmark to be noticed at speed from the motorway; while from a circling plane, the white slab would glare among the dull grey and brown of its hinterland.

The bus was off the access road now, onto the MetaCentre’s own road network: bright yellow signs pointed to freight loading, exhibitors’ entrances, bus and coach drop-off. Flowerbeds planted with immature shrubs were wrapped in shiny black plastic, a fetishist’s garden. There, again, was the ascending loop and expressive steel and glass of the unfinished pedestrian bridge. A handshake the size of a basketball court dominated the white membrane of the façade, overwritten with the words WELCOME MEETEX: TOMORROW’S CONVENTIONS TODAY. This was accompanied by multi-storey exhortations from a telepresence software company: JOIN EVERYONE EVERYWHERE.

A zigzag kerb, coaches nosing up to it diagonally. We dropped out of the front door one by one in the stunned way common to bus passengers, however long their journey. But we recovered quickly – no one lingered in the half-rain – and we scurried towards the endless glass doors of the MetaCentre, past an inflatable credit card that shuddered and jerked against the ropes securing it to the concrete forecourt.

Hot air blasted me from above, a welcoming blessing from the centre’s environmental controls. Thinking about my hair, I ran a hand through it, a wholly involuntary action. Grey carpet flecked with yellow. Behind me, someone said, ‘Next year we’re going to Tenerife, but I don’t want it to be just a box-ticking exercise.’ Queues navigated ribboned routes to registration and information desks. Memory-jogged, I fished my credentials out of my jacket pocket and slipped the vile lanyard over my head. Door staff approved me with a flicker of their eyes.

A broad ramp poured people down into the main hall of the MetaCentre. Gravity-assisted, like components on a production line or animals in a slaughter-house, we descended, enormous numbers of us – a whole landscape shaped to cope with insect quantities of people. Hundreds of miles of vile yellow lanyard had been woven, stitched with METACENTRE METACENTRE METACENTRE thousands of times to be draped around thousands of necks now prickling in the bright light and outside-inside air of the hall. Ahead of us, and already around us, were the exhibitors, in their hundreds, waiting for all those eyes and credentials and job titles to sluice past them. There is the expectant first-day sense that business must be transacted, contacts must be forged, advantages must be gleaned, trends must be identified, value must be added, the whole enterprise must be made worthwhile. Everyone is at the point where investment has ceased and the benefits must accrue. A shared hunger, now within reach of the means of fulfilment. Like religion, but better; provable, practical, purposeful, profitable.

At another fair, in other company, these thoughts might have been mine alone. Not here. All those thousands of conferences, expos and trade fairs around the world, of which I have attended scores if not hundreds – their squadrons of organisers comprise, naturally enough, an industry in itself. And, also naturally enough, this industry revels in get-togethers. It wants, it truly needs, its own conferences, meetings, summits and expos. Its people spend their lives selling face-to-face, handshake, eye contact, touch and feel, up close and personal, in the flesh, meet and greet. They believe their own pitch – of course they do. They actually think they are telling the truth, rather than just hawking a product. (Our pitch is very different.)

A conference of conference organisers. A meeting of the meetings industry. And they all knew the recursive nature of their gathering here – they all joked about it, essentially telling the same joke over and over, draining it of meaning until it is nothing more than a ritualised husk, but they laugh all the same. Just a conference of conference organisers, one among many – Meetex joins EIBTM, IMEX, ICOMEX, EMIF and Confex on the calendar, and all of those will include the same jokes and the same small talk, redundancy piled on redundancy, spread out across the globe. This repetition proliferating year after year was enough to bring on a headache. And indeed a headache had stirred since I left the hotel, accelerated perhaps by the stuffy bus and its throbbing engine, its boomerang route, the swinging 360-degree turn it had made around the motorway junction.

Hosting Meetex was a smart move by the MetaCentre – this space, which could swallow aircraft hangars whole, was in a way the biggest stall at the fair, advertising its services to the people who, captivated by its quality as a venue, would fill it with gatherings of other industries in the coming years. The airport! The motorway! The convenience! The state-of-the-art facilities! The thousands of enclosed square metres! A space without architecture, without nature, where everything outside is held at bay and there is no inside – no edges, the breezeblock walls too distant to see, a blankness above the steel frame supporting scores of lights. But inside this hall was a space with too much design. The fair, the exhibitors, all exhibiting. It was an assault on the eyes, a chaos of detail, several hundred simultaneous demands on your attention. And it was active, it came to you with bleached teeth and a tight T-shirt. Many stands were attended by attractive young women, brightly dressed and full of vim; there must be an inoffensive technical term for them, perhaps along the lines of ‘brand image enhancement agents’, but they are mostly referred to as booth babes. They jump out at you, try to coax you to try a game or join a list, or they hand you a flier or a low-value freebie like a USB stick or a tote bag.

Combined, these multitudinous pleas – each an invitation to enter a different corporate mental universe and devote yourself to it; invitations that are the product of enormous investments of time and money and creativity – formed a barrage of imagery and information and signs and symbols that at first challenged the brain’s ability to process its surroundings, becoming an undifferentiated blaze of visual abundance, overwhelming our monkey apparatus like lens flare. Which was precisely the point – it was in the interest of the organisers and the host to dazzle you, to leave the impression that there’s not just enough on show, there’s more than enough, far more than enough, a stupefying level of surplus. For a fair to imply that it might have limits is anathema – that’s why they rain down the stats and the superlatives, the square metres and the daily footfall, the record numbers of this and that. What other industry stressed that its product was near-impossible to consume? No wonder my services were needed. Adam was a genius.

It wasn’t impossible to see a whole show on this scale, but it was difficult. It took work. You had to be systematic, go aisle by aisle, moving up the hall in a zigzag, giving every stand some time but not so much time that it diminished the time given to others. That used to be my approach, but I found that route planning and time management occupied more of my thoughts than the content of the show itself. I was lost in the game of trying to see every stand, note every new product and expose myself to every scrap of stimuli – the show as a whole left only a shallow track on my memory. And my reports were similarly shallow. They were even-handed but lacked any texture; they were mere aggregations of data. In being systematic, I saw only my own system. Completism was blindness: it yielded only a partial view.

After a year of trudging around fairs in this manner, I realised my reports were formulaic and stale, full of ritual phrases and repeated structures. And the entire point of the endeavour was to spare clients that endless repetition. They employed me because they already knew the routine aspects of these fairs or didn’t care to know them – what they wanted was something else. So I threw away my diligent systems and timetables and started to truly explore. Today was typical of my current method of not having a method – I would strike out into the centre of the hall, ignoring all pleas and distractions, and from there walk without direction. I would try to drift, to allow myself to be carried by the current and eddies of the hall, thinking only in the moment, watching and following the people around me. Beyond that, I tried to think as little as possible about my overall aims and as much as possible about what was in front of me at any given time. I would give myself to the experience, keep my notes sparse, take a few photos. It’s not easy to be purposefully random, but it pays. Once I started taking this approach, my reports became colourful and impressionistic. They were filled with telling details and quirky insights. The imperfection of memory became a strength.

It’s only on the second and subsequent days of a fair that I seek out the specifics that clients have requested and conduct any enquiries they might have asked for. More detail accrues naturally, organically, around these small quests.

Surrounded by conference organisers, I am the only professional conference-goer. It’s what I do; nothing else. And they – the people here, the exhibitors, the venues, the visitors, the whole meetings industry – have no idea.

The stands passed by, hawking bulk nametags, audiovisual equipment, seating systems, serviced office space. Not just office space – all kinds of space are packaged and marketed here, and places too. You can get a good deal, a great deal, on Vietnamese-made wholesale tote bags at Meetex, but what it and its competitors mostly trade in is locations. Excuse me, ‘destinations’. Cities, regions, countries; all were ideal for your event, whether they were Wroclaw, Arizona or Sri Lanka, or Taipei, Oaxaca or Israel. All combined history and modernity. All were the accessible crossroads of their part of the world. All were gateways and hearts. All had state-of-the-art facilities that could be relied upon. All had luxurious yet affordable hotels. Most importantly, all of these hundreds of places across the world were distinctive, unique and outstanding. Consistently, uniformly so.

Those comfortable, cost-effective hotels and state-of-the-art facilities were also present at Meetex. Other conference centres promoted themselves, boasting of the inexhaustible square kilometres they had available on scores of city outskirts. Within a giant space, I was being coaxed to other giant spaces; a fractal shed-world, halls within halls within halls.

Another section was devoted to the chain hotels, and its promises of pampering and revitalisation were hard to bear. Women wrapped in blinding white towels, cucumber slices over eyes. Men, ties AWOL, drinking beer in vibrant bars. Couples clinking capacious wine glasses over gourmet meals. Clean linen, gleaming bathrooms, spectacular views. These were highly seductive images for me. I wanted to be back at the hotel, reclining on the bed, taking a long shower, ordering a room service meal, perhaps with some wine thrown in.

It mattered little that the images were a total fiction – posed by models, supplied by stock photo agencies, the gourmet food made of plastic, the views computer generated, the bar a stage set – the desire they generated was real. Meetex was dominated by these deceitful images, defined by them. The location on sale is immaterial. The picture, the money shot, is nearly identical everywhere: a gender-mixed, multicultural group unites around an arm-outstretched, gap-bridging handshake, glorying in it; gameshow smiles all round, with an ancient monument or expressive work of modern architecture as the backdrop. Business! Being Done! The transcendent, holy moment when The Deal is Struck. Everyone profits! And in unique, iconic, spectacular surroundings, heaving with antiquities and avant-garde structures, the people bland and attractive, their skin tones a tolerant variety but all much alike, looking as if they have just agreed the sale of the world’s funniest and most tasteful joke while standing in the lobby of a Zaha Hadid museum.

If only they looked around. Business was done in places like the Way Inn, or in giant sheds like the MetaCentre. Properly homogenised environments, purged of real character like an operating theatre is rid of germs. Clean, uncorrupt. That’s where deals are struck – in the Grey Labyrinth. And that’s where I headed, because I had business to attend to.

The Grey Labyrinth took up the rear third of the centre’s main hall. This space was set aside for meetings, negotiations and deal-making, subdivided into dozens of small rooms where people could talk in private. It was the opposite of the visual overload of the fair, a complex of grey fabric-covered partitions with no decoration and few signs. All sounds were muffled by the acoustic panels. The little numbered cubicles were the most basic space possible for business – a phone line, a conference table topped with a hard white composite material, some office chairs. Sometimes they included a potted plant, or adverts for the sponsor company that had supplied the furnishings. Mass-produced bubbles of space, available by the half-hour, where visitors video-conferenced with their home office or did handshake deals. They loved to talk about the handshake, about eye contact, about the chairman’s Mont Blanc on a paper contract – these anatomical cues you could only get from meeting face to face. They wanted primal authenticity, something that could be simulated but could never be equalled. But it all took place in a completely synthetic environment – four noise-deadening, view-screening modular panels, a table, some chairs, a phone line. Or, nowadays, a well-filled wifi bath in place of the latter.

I had booked cubicle M-A2-54 for 10.30 a.m. It was empty when I arrived, four unoccupied office chairs around a small round table. A blank whiteboard on a grey board wall. No preparation was needed for the meeting and I sat quietly, drumming my fingers on the hard surface of the table, listening to the muted sounds that carried over the partitions.

The prospect was seven minutes late, but I didn’t let my irritation show when he arrived, and greeted him with the warm smile and firm handshake I know his kind admire.

‘Neil Double. Pleasure to meet you.’ False – I am indifferent about the experience. Foolish to place so much faith in a currency that is so easily counterfeited.

‘Tom Graham. Likewise.’ Graham was an inch or two shorter than me but much more substantial – a man who had been built for rugby but, in his forties, was letting that muscle turn to butter in the rugby club bar. His thick neck was red under the collar of his Thomas Pink shirt. Curly black hair, sprinkled with grey, over the confident features of a moderately successful man. We sat opposite each other.

‘So, Tom, why are you here?’

He jutted his bottom lip out and made a display of considering the question.

‘A friend told me about your service, and I wanted to find out more about it.’

Word of mouth, of course – we don’t advertise.

‘I meant,’ I said, ‘why are you here at the conference? Aren’t there places you would rather be? Back at the office, getting things done? At home with your family?’

‘Aha,’ Tom said. ‘I see where you’re going.’

‘Conferences and trade fairs are hugely costly,’ I said. ‘Tickets can cost more than £200, and on top of that you’ve got travel and hotel expenses, and up to a week of your valuable time. And for what? When businesses have to watch every penny, is that really an appropriate use of your resources?’

‘They can be very useful.’

‘Absolutely. But can you honestly say you enjoy them? The flights, the buses, the queues, the crowds, the bad food, the dull hotels?’

Tom didn’t answer. His expression was curious – not interested so much as appraising. I had an unsettling feeling that I had seen him before.

I continued. ‘What if there was a way of getting the useful parts of a conference – the vitamins, the nutritious tidbits of information that justify the whole experience – and stripping out all the bloat and the boredom?’

‘Is there?’

‘Yes. That’s what my company does.’

I am a conference surrogate. I go to these conferences and trade fairs so you don’t have to. You can stay snug at home or in the office and when the conference is over you’ll get a tailored report from me containing everything of value you might have derived from three days in a hinterland hotel. What these people crave is insight, the fresh or illuminating perspective. Adam’s research had shown that people only needed to gather one original insight per day to feel a conference had been worthwhile. These insights were small beer, such as ‘printer companies make their money selling ink, not printers’ or ‘praise in public, criticise in private’. But if Graham got back from a three-day conference with three or four of those ready to trot out in meetings, he’d feel the time had been well spent. That might sound like a very small return on investment, and it is, but these are the same people who will happily gnaw through cubic metres of airport-bookshop management tome in order to glean the three rules of this and seven secrets of that. Above those eye-catching brain sparkles, a handful of tips, trends and rumours is all that sticks in the memory from these events, and they can get that from my report, plus any specific information they request. Want to know what a particular company is launching this year? Easy. Want a couple of colourful anecdotes that will give others the impression you were at the event? Done. Just want to be reassured that you didn’t miss anything? My speciality.

And if you want to meet people at the conference, be there in person, look people in the eye and press the flesh – well, we can provide that as well. I’ll go in your place. Companies use serviced office space on short lets, the exhibitors here have got models standing in for employees and they use stock photography to illustrate what they do. That pretty girl wearing the headset on the corporate website? Convex can provide the same professional service in personal-presence surrogacy. We can provide a physical, presentable avatar to represent you. Me. And I can represent dozens of clients at once for the price of one ticket and one hotel room, passing on the savings to the client.

Of course I still have to deal with the rigmarole of actual attendance, but the difference is that I love it. Permanent migration from fair to fair, conference to conference: this is the life I sought, the job I realised I had been born to do as soon as Adam explained his idea to me, at a conference, three years ago. It is not that I like conferences and trade fairs in themselves – they can be diverting, but often they are dreary. In their specifics, I can take them or leave them – indeed, I have to, when I am with machine-tools manufacturers one day and grocers the next. But I revel in their generalities – the hotels, the flights, the pervasive anonymity and the licence that comes with that. I love to float in that world, unidentified, working to my own agenda. And out of all those generalities I love hotels the most: their discretion, their solicitude, their sense of insulation and isolation. The global hotel chains are the archipelago I call home. People say that they are lonely places, but for me that simply means that they are places where only my needs are important, and that my comfort is the highest achievement our technological civilisation can aspire to. When surrounded by yammering nonentities, solitude is far from undesirable. Around me, tens of thousands are trooping through the concourses of the MetaCentre, and my cube of private space on the other side of the motorway has an obvious charm.

Tom Graham appeared to be intrigued by conference surrogacy, and asked a few detailed questions about procedures and fees, but it was hard to tell if he would become a client or not. And if he did sign up, I wouldn’t necessarily know. Discretion was fundamental to Adam’s vision for our young profession – clients’ names were strictly controlled even within the company, as a courtesy to any executives who might prefer their colleagues not know that someone was doing their homework for them. Today, for instance, I knew that clients had requested I attend two sessions, one at 11.30 and one at 2.30, but I had no idea who or why. After the second session, my time would be my own – I could slip back to the hotel for a few hours of leisure before the party in the evening.

A few hours of leisure … The thought of my peaceful room, its well-tuned lighting, its television and radio, filled me with a sense of longing, the strength of which surprised me. It was almost a yearning. Right now, I imagined, a chambermaid would be arranging the sheets and replacing the towel and shower gel I had used. Smoothing and wiping. Emptying and refilling. Arranging and removing. Making ready.