Полная версия

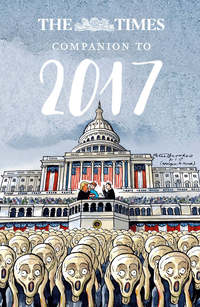

The Times Companion to 2017: The best writing from The Times

In the documentary, Beard, the director, says to Ash: “Some people change their minds …”

“Some people. Not me,” she responds. Do you think you’ll be a girl for ever, he asks. “Yes,” she replies. And turns a cartwheel.

A BARE-KNUCKLE FIGHTER IN THE BLOODIEST CONTEST EVER

Rhys Blakely

NOVEMBER 8 2016

IT BEGAN WITH a ride down a golden escalator in the marble atrium of a New York skyscraper. It was June 16, last year, and Donald Trump was announcing a run for the White House. America had no idea what was about to hit it.

Some of the crowd had been paid $50 apiece to turn up at that first campaign event and Mr Trump made headlines with a 40-minute speech in which he praised his golf courses, promised to build a “great wall” along the southern border and called Mexican immigrants rapists. The most wildly unpredictable US election in living memory had begun.

In the months to come, Mr Trump would feud with the family of a fallen Muslim soldier, a Hispanic beauty queen, the leadership of his party, and the Pope. Defying the pundits, this former reality TV star, whose divorces and sex life had kept New York’s tabloids entranced for decades, would become the first presidential nominee of a major US party to have no experience in office since Eisenhower and the very first to have boasted about the size of his manhood in a presidential primary debate.

On the Democratic side, Hillary Clinton would face another populist. The former secretary of state announced her candidacy in April last year. She set off on an image-softening road trip to Iowa. The path ahead was rockier than she imagined. The rivals she feared most — Joe Biden, the vice-president, and Elizabeth Warren, the Massachusetts senator — stayed out of the race. But Bernie Sanders, a septuagenarian socialist senator from Vermont, would electrify Democrats suspicious of Mrs Clinton’s ethics, her ties to big business and her support for free trade.

She endured a bruising primary while the FBI investigated a secret email system she used while leading the State Department. In February Mr Sanders effectively battled her to a tie in the Iowa caucus, the first primary contest, and then trounced her in New Hampshire. Mrs Clinton was running to be the first woman president, but young women shunned her candidacy.

As the primary race headed to the South, black voters saved her campaign. But questions lingered over whether she could animate Obama voters. She emerged as the second most unpopular nominee of a major US party since polling began. The silver lining? She was running against the first.

It was often predicted that Mr Trump’s candidacy would fade. Seventeen Republicans had thrown their hat into the ring: it was a good year to run as a member of the Grand Old Party. A Democrat had occupied the White House for two terms, and rarely has a party kept it for three. Most voters thought the country was on the wrong track. There were six past and current Republican governors and five senators in the race.

Few thought that a brash, twice-divorced celebrity could make a mark. Early on, though, Mr Trump displayed two skills. The first was for attracting media coverage. His mastery of Twitter and of insults bamboozled his rivals. It was estimated that he garnered “free” media coverage worth $2 billion.

The second skill was reaching voters who felt overlooked and left behind, especially white men without a college education. His candidacy coincided with a new scepticism about what he called “the siren song of globalisation”.

Mr Trump’s diatribes against political correctness, free trade and illegal immigration electrified a section of the right. Supporters quickly forged a consensus on what made him special: his outspokenness, his business acumen, wealth that made him immune to cronyism and his outsider status.

At his first “town hall” event, in the critical early voting state of New Hampshire, Jim Donahue, 65, a maths teacher, thought that Mr Trump could be “America’s Vladimir Putin — a nationalist to make the people think that the country could be great again”.

It was not until the first Republican primary debate, on August 7 last year, that his rivals realised that Mr Trump was a threat. He was leading the polls and placed at the centre of the stage. His demeanour was glowering, his tan a striking shade of orange. In the opening seconds, the moderators asked the ten men who had qualified to participate if any would refuse to rule out running as an independent in the election.

A theatrical pause — then one hand crept up: Mr Trump’s, of course. The crowd booed this challenge to Ronald Reagan’s 11th commandment: thou shalt not turn on a fellow Republican. The atmosphere was somewhere between game show and a bare-knuckle boxing match. It was riveting television. The audience broke records.

That evening, aides of Marco Rubio, the Florida senator whom the Clinton campaign feared the most, realised something: untethered to an ideology, unburdened by a respect for facts, and willing to say things no other candidate would dare, Mr Trump was unmanageable.

But that first debate also highlighted his flaws. Megyn Kelly, a star presenter, confronted him on how he had called women “fat pigs, dogs, slobs and disgusting animals”. Later that evening he was swarmed by a mob of reporters. Amid the mêlée, Mr Trump fumed. “I think Megyn behaved very nasty to me,” he said. That night he retweeted a message that called her a “bimbo”. He later suggested that she had asked him unfair questions because she had been menstruating.

That pattern would recur: Mr Trump could not let slights slide. Fourteen months later, when they met for three presidential debates, Mrs Clinton, apparently on the advice of psychologists, baited him. In Las Vegas she said he would be a “puppet” of Vladimir Putin. Mr Trump could barely contain his fury. “No puppet. No puppet,” he spluttered. “You’re the puppet.”

Voters were already worried about his temperament. In the final days of the campaign his aides had blocked him from Twitter, to stop the acts of self-sabotage that frequently cost him support. His treatment of women would come back to haunt him, too.

The summer of last year, however, became known as the “summer of Trump”. While the Clinton campaign churned out thousands of words of policy proposals and dodged press conferences, Mr Trump did things no candidate had ever done. At a fair in Iowa he gave children rides on his helicopter. He spent more money on “Make America Great Again” baseball hats than on polling. He demurred when he was asked to denounce a leader of the KKK. He did not release his taxes. He had fun: “We will have so much winning if I get elected that you may get bored with winning,” he said.

Last February a second place in the Iowa caucuses for Mr Trump was followed by a victory in the New Hampshire primary. As the primaries headed first to the conservative Deep South and then north to the rust-belt states of the upper Midwest and the industrial Northeast, Mr Trump kept on winning. May 4 marked the Indiana primary. Mr Trump started his day by alleging without a shred of evidence that the father of Mr Cruz, one of only two rivals still standing, had helped to assassinate President Kennedy. By the end of the day the contest was over: Mr Trump was the Republicans’ presumptive presidential nominee.

Mrs Clinton, meanwhile, was making campaigning look like solemn work. In July the FBI said it would not recommend charges after investigating whether she had broken the law by using a private email server. The revival of that investigation ten days before the election would send Democrats reeling, and the unflattering inner workings of Mrs Clinton’s campaign were revealed when private emails were hacked, probably by Russia.

Time and again, though, Mr Trump defied the laws of political gravity. He won the votes of evangelical Christians despite saying: “I’m not sure I have ever asked God’s forgiveness.” He said: “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters.”

He called the voters of Iowa “stupid”. He said that women who had abortions should be punished. The leaders of his own party denounced his attacks on a Hispanic judge as racist. He made remarks some interpreted as promoting violence against Mrs Clinton. He was forced to fire his second campaign manager over alleged links to Kremlin-sponsored strongmen, praised Mr Putin and asked Moscow to hack Mrs Clinton. In the final presidential debate, he suggested he might keep the country “in suspense” and not accept the results of the election.

America has seen populists before. None, though, rose as far or as fast. US politics will never be the same.

LEONARD COHEN

Obituary

NOVEMBER 11 2016

FOR SOMEONE WHOSE songs earned him the epithet “the godfather of gloom”, Leonard Cohen had a highly developed and mischievous sense of humour. “I don’t consider myself a pessimist,” he noted. “I think of a pessimist as someone who is waiting for it to rain — and I feel soaked to the skin.”

The subject of his songs over a career that spanned half a century was the human condition, which inevitably led him into some dark places. He suffered bouts of depression and his mournful voice and the fatalism of his lyrics led his songs to be adopted by the anguished, lovelorn and angst-ridden as a personal liturgy.

However, there were also what Cohen called “the cracks where the light gets in”. Despite his image as a purveyor of gloom and doom, the inherent melancholia of his songs was nuanced not only by deep romanticism but by black humour.

A published poet and novelist who was in his thirties before he turned to music, Cohen was the most literate singer-songwriter of his age. With Bob Dylan, he occupied the penthouse suite of what he called “the tower of song”. Together Cohen and Dylan not only transformed the disposable, sentimental métier of popular music into something more poetic and profound but, for better or worse, made the pop lyric perhaps the defining form of latter 20th-century expression. In an era in which anyone who warbled about “the unicorns of my mind” was liable to be hailed as a poet, Cohen was the genuine article.

Many of his best-known songs — Suzanne, So Long, Marianne and Sisters of Mercy — were romantically inspired by the women in his life. In Chelsea Hotel #2, the theme of longing, love and loss turned to pure lust as he described a liaison with the singer Janis Joplin as she gave him “head on the unmade bed/ While the limousines wait in the street”.

Story of Isaac and The Butcher touched on religious themes, and war and death loomed large, particularly after his experiences during the 1973 Arab-Israeli war when he offered to fight for Israel and ended up performing for Jewish troops in a tank division that was under fire in the Sinai desert.

Depression and suicide also informed several songs, including Seems So Long Ago, Nancy and Dress Rehearsal Rag. This tendency to lapse into morbidity led one critic to wail, “Where does he get the neck to stand before an audience and groan out those monstrous anthems of amorous self-commiseration?” Yet if his writing had a philosophical stock-in-trade, it was more stoical perseverance than the abandonment of hope.

Many of his compositions shared a search for self and meaning and were driven by a restless quest for personal freedom, nowhere more so than on Bird On The Wire, which opened with probably his most quoted lines “Like a bird on the wire/ Like a drunk in a midnight choir/ I have tried in my way to be free”.

The song was covered by dozens of artists, including Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Judy Collins and Joe Cocker, and was once memorably described as a bohemian version of My Way, sans the braggadocio.

Even at his darkest, the prospect of redemption and perhaps even a glimmer of salvation was evident. He described Hallelujah, perhaps his best-known composition — and certainly his most covered, with some 300 versions performed or recorded by other artists — as an affirmation of his “faith in life, not in some formal religious way but with enthusiasm, with emotion”.

The song took him years to write as he pared back 80 draft verses until each line felt right, as with the second verse: “Your faith was strong but you needed proof/ You saw her bathing on the roof/ Her beauty and the moonlight overthrew you/ She tied you to a kitchen chair/ She broke your throne, and she cut your hair/ And from your lips she drew the hallelujah.”

It was characteristic of the meticulous way he worked to make every word count and led to a well-documented exchange with Bob Dylan, who expressed his admiration for the song: “He asked me how long it took to write, and I lied and said three or four years when actually it took five. Then we were talking about one of his songs, and he said it took him 15 minutes.”

Unfailingly courteous and possessed of an unfashionably old-world charm, Cohen’s intellectual coming of age predated the advent of rock’n’roll. His early cultural heroes were not Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry but the beat writer Jack Kerouac and the poet Lorca, after whom Cohen named his daughter. His artistic leanings were liberal and bohemian, but he was never a hippy. Dressed in dark, tailored suits and smart fedoras, he had an elegance that was perhaps the legacy of his Jewish father, who owned a clothing shop. Sylvie Simmons, his biographer, reckoned he looked “like a Rat Pack rabbi, God’s chosen mobster”.

He spoke in a sonorous voice that was full of a reassuring calm and yet animated at the same time. If it was a great speaking voice, it was perhaps not a natural vehicle for a singer, although he developed his own idiosyncratic style to overcome its limitations, one which was compared by the critic Maurice Rosenbaum to a strangely appealing buzz-saw: “I knew I was no great shakes as a singer,” Cohen said, “but I always thought I could tell the truth about a song. I liked those singers who would just lay out their predicament and tell their story, and I thought I could be one of those guys.”

He was handsome in a rugged and swarthy way, and women found the combination of his physical attraction and the sensitivity of his poetic mind to be irresistible. In turn he described love as “the most challenging activity humans get into” and took up the gauntlet with prolific enthusiasm. “I don’t think anyone masters the heart. It continues to cook like a shish kebab, bubbling and sizzling in everyone’s breast,” he said.

Yet whether love ever bought him true happiness is debatable, and in his 2006 poetry collection, Book of Longing, he mocked his reputation as a ladies’ man as an ill-fitting joke that “caused me to laugh bitterly through the ten thousand nights I spent alone”.

He never married but perhaps came closest to contentment with Marianne Ihlen, the inspiration behind several of his early songs and with whom he lived on the Greek island of Hydra in the 1960s. Their relationship lasted a decade through numerous infidelities. He also had a long relationship with the artist and photographer Suzanne Elrod, with whom he had two children. His son, Adam Cohen, is a singer-songwriter who produced his father’s 2016 album You Want It Darker. His daughter, Lorca, is a photographer, who gave birth to a surrogate daughter for the singer Rufus Wainwright and Jörn Weisbrodt, his partner.

For all his protests to the contrary, his love life was complicated, almost Byronic in its profligacy. As well as his assignations with Janis Joplin and Joni Mitchell, for example, he rested his head on the perfumed pillows of the fashion photographer Dominique Issermann, the actress Rebecca De Mornay and the songwriter Anjani Thomas. Mitchell, who once said the only men to whom she was a groupie were Picasso and Cohen, celebrated their year-long relationship in several songs, including A Case of You, in which her lover declares himself to be as “constant as a northern star”. He certainly was not, and yet she sang that he remains in her blood “like holy wine”.

Summing up Cohen’s lifelong serial inconstancy, his biographer, Simmons, wrote that his “romantic relationships tended to get in the way of the isolation and space, the distance and longing, that his writing required”.

Yet he was as fixated on metaphysical matters as he was on carnal pleasures, and many of his best lyrics fused the erotic and the spiritual. In the 1990s his search for enlightenment resulted in him disappearing from public view to live an ascetic life in a Zen Buddhist monastery on the snow-capped Mount Baldy in California. Although he remained a practising Jew, he was ordained as a Buddhist monk in 1996.

He came down from the mountain three years later and returned to civilian life, only to find that while he was sequestered he had been robbed by his longtime manager (and, perhaps inevitably, former lover), Kelley Lynch. He issued legal proceedings against her for misappropriating millions from his retirement fund and swindling him out of his publishing rights. Left with a huge tax bill and a relatively modest $150,000, he remortgaged his home. He was awarded $9 million by a Los Angeles court in 2006.

When Lynch — who was later jailed after violating a court order to keep away from Cohen — was unable to pay, he undertook his first concert tour in 15 years to replenish his funds. It was estimated by Billboard magazine that he earned almost $10 million from the 2009 leg of the tour alone.

A golden period of late creativity followed. After releasing a parsimonious 11 studio albums in 45 years, he released three in four years between 2012 and 2016, including Old Ideas, which became the highest-charting album of his career, when he was 76.

Leonard Norman Cohen was born in Montreal in 1934 into a prosperous and middle-class Jewish family. His father was already approaching 50 when his son was born, and died when Cohen was nine years old, leaving him with a small trust fund income. His mother, Masha, was the daughter of a rabbi and brought him up steeped in Talmudic lore and the stories of the Old Testament. He later recalled a “Messianic” childhood.

In an era before rock’n’roll he was drawn to the folk and country music he heard on the radio. He learnt to play the guitar as a teenager “to impress girls” and formed a group called the Buckskin Boys. Women also loomed large in his adolescent life. After reading a book about hypnosis, he tried out the technique and persuaded the family’s maid to disrobe. He was 13 at the time.

At the age of 15 he stumbled on a volume by the Spanish poet Federico García Lorca in a second-hand bookshop in Montreal. Inspired by Lorca’s erotic themes, he decided to become a writer and adopted his lifelong credo that his creative muse was best served via the entanglement of heart and limbs.

At McGill University he chaired the debating society and won a prize for creative writing. His first book of verse, Let Us Compare Mythologies, appeared in 1956. A second volume, The Spice-Box of Earth, was published five years later and put him on the literary map. By then wanderlust had set in and he travelled widely, spending time in Castro’s Cuba before buying a small house without electricity or running water on the Greek island of Hydra. There he wrote further books of verse and the novels The Favourite Game and Beautiful Losers, as well as conducting a decade-long romantic relationship with Ihlen.

His books were critically acclaimed and one enthusiastic reviewer gushingly likened Beautiful Losers to James Joyce. But good reviews don’t put food on even Greek tables and his books initially sold fewer than 3,000 copies. In need of cash, he returned to north America in 1966, planning to try his luck as a singer and songwriter in Nashville.

“In retrospect, writing books seems the height of folly, but I liked the life,” he recalled. “It’s good to hit that desk every day. There’s a lot of order to it that is very different from the life of a rock’n’roller. I turned to professional singing as a remedy for an economic collapse.”

He never got as far as Nashville. After landing in New York, he was “ambushed” by the new music he heard all around him. “In Greece I’d been listening to Armed Forces Radio, which was mostly country music,” he said. “But then I heard Dylan and Baez and Judy Collins, and I thought something was opening up, so I borrowed some money and moved into the Chelsea Hotel.”

Collins became the first to record one of his songs and invited him to sing with her on stage. His first live performance caused him to flee with stage fright, but his shyness appealed to the audience who encouraged him back and set him on his new career as a troubadour. Already in his thirties, he was described by one critic as having “the stoop of an aged crop-picker and the face of a curious little boy”.

His singing, too, provoked mixed reactions but John Hammond, the legendary Columbia A&R man who had already signed Bob Dylan to the label, was not one to be put off by an unconventional voice. “He took me to lunch and then we went back to the Chelsea,” Cohen remembered. “I played a few songs and he gave me a contract.”

He spent two years living in the Chelsea Hotel, fell in with Andy Warhol’s set, became infatuated with the Velvet Underground’s German chanteuse Nico and released his debut album. Sales in America were initially modest but the record found a cult following in Europe and Britain, where he was dubbed “the bard of the bedsits”.

Among his most memorable concerts from this time was his appearance at the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970. Unpromisingly he had to go on after an electrifying performance by Jimi Hendrix, yet instead of bringing down the mood he managed to win over the pumped-up, 600,000-strong crowd by telling them gentle self-deprecating anecdotes in a hushed voice, in between his equally low-key numbers.

Although his early records sounded austere, centred around little more than his voice and a softly strummed guitar, in later years he expanded his musical palette, adding a full band and chorus of backing singers. Initially he appeared to be a literary aesthete, aloof from the hurly-burly of rock’n’roll, but by the mid-1970s his life was unravelling in a midlife crisis in which LSD experimentation featured. “I got into drugs and drinking and women and travel and feeling that I was part of a motorcycle gang or something,” he admitted 20 years later.

His confusion led him to record with Phil Spector, whose production banished the simplicity of his earlier recordings in favour of melodramatic rock arrangements. One grotesque track, Don’t Go Home With Your Hard On, featured a drunken chorus of Cohen, Dylan and Allen Ginsberg repeating the title line over and over again.

Working with the volatile Spector was a fraught process. “I was flipped out at the time and he certainly was flipped out,” Cohen recalled. “For me, the expression was withdrawal and melancholy, and for him, megalomania and insanity and a devotion to armaments that was really intolerable.”

At one point during the sessions, Spector locked Cohen out of the studio, put an armed guard on the door and would not let him listen to the mixes. When Cohen protested, Spector threatened him with a gun and a cross-bow.

The resulting album, Death of a Ladies’ Man in 1977, was a career nadir that horrified his fan base, and he swiftly returned to something closer to his old style. When five years passed between the release of albums it appeared that his inspiration had dried up, a blockage that he later attributed to having become addicted to amphetamines. Various Positions in 1984 was a triumph and included Hallelujah. It sparked a revival both creatively and commercially as Cohen adopted the mode of a fashionable boulevardier.

With an increasingly sardonic humour he surveyed the wreckage of the modern world in songs such as First We Take Manhattan, Democracy and Everybody Knows and painted an apocalyptic picture of the world. It was a vision that struck a hellish chord with the film director Oliver Stone who included three of Cohen’s songs from the period in his horrifyingly violent, dystopian movie Natural Born Killers. Shortly after the film’s release, Cohen retreated to his Zen Buddhist monastery.