Полная версия

The Strategist: Be the Leader Your Business Needs

Five years ago, when I first started teaching in EOP, I heard the program described as challenging and transformative. At the time, “challenging” struck me as right, but “transformative” seemed closer to hype. Having seen it happen again and again, I now share the optimism.

As our orientation session draws to a close, I join the executives and fellow faculty as we head en masse to Kresge Hall for cocktails and dinner. Our work is about to begin in earnest.

In all my classes, I pose one fundamental question: “Are you a strategist?” Sometimes it’s spoken, often it’s only implicit, but it’s always there. We talk about the questions strategists ask, about how strategists think, about what strategists do. My intent is not to coach these executives in strategy in the way they might learn finance or marketing. As business heads, they aren’t going to be functional specialists. But they do need to be strategists.

Are you a strategist?

It’s a question all business leaders must answer because strategy is so bedrock crucial to every company. No matter how hard you and your people work, no matter how wonderful your culture, no matter how good your products, or how noble your motives, if you don’t get strategy right, everything else you do is at risk.

My goal in this book is to help you develop the skills and sensibilities this role demands, and to encourage you to answer the question for yourself. It’s a difficult role and it may be tempting to try to sidestep it. It requires a level of courage and openness to ask the fundamental questions about your company and to live with those questions day after day. But little you do as a leader is likely to matter more.

2

ARE YOU A STRATEGIST?

HERE’S A TEST of your strategic thinking. It’s the same one I give my EOPers right at the beginning of the course.

Step into the shoes of Richard Manoogian, CEO of Masco Corporation, a highly successful company on the verge of a momentous decision.1 You’ve got a big pile of money and must decide whether to invest it in a far-reaching new business venture. The stakes are high, and it’s not an easy or obvious decision. If you don’t go ahead, you could be passing up an opportunity for growth in a new direction and hundreds of millions of dollars in future profits. If you take the plunge and turn out to be wrong, you may have wasted $1–2 billion. Either way, you will have to live with the results for many years.

To make the decision, you’ll first need to know something about Masco and its marketplace. The story begins more than two decades ago, but its lessons are timeless, and the intervening years allow us to take a long view on the company and the industry.

FIRST, CONSIDER THE COMPANY

It’s 1986. Masco is a successful $1.15 billion company that has just recorded its twenty-ninth consecutive year of earnings growth. Its ability to wring outsized profits out of industries that are neither high tech nor glamorous has won it the monicker of “Master of the Mundane” on Wall Street. Its portfolio includes faucets, kitchen and bathroom cabinets, locks and building hardware, and a variety of other household products.2 Masco expects the businesses to generate $2 billion in free cash flow over the next few years.

What would you do with all that money? Masco’s leaders want to tackle other mundane businesses where their prowess can “change the game.” They envision becoming the “Procter & Gamble of consumer durables.” In their immediate sights is the U.S. household furniture business, where they see another opportunity to seize profitable dominance of a sleepy industry.

Is Manoogian’s idea a promising one? If so, is Masco the company to lead the charge?

When I raise these questions the first morning in class, the executives don’t immediately jump up. Like you, they enjoy being the decision maker; it’s the role they play in their real-life jobs, but they’re reluctant to put themselves on the line with a group they’ve just met. With some coaxing, though, we’re soon deep into Masco’s situation and the issues Manoogian faces.

The case for Manoogian’s strategy looks compelling. Through a long record of triumphs in durable goods industries, Masco distinguished itself through efficient manufacturing, good management, and innovation. Its biggest success to date was reinventing the faucet business. Prior to Masco’s entry, the industry was highly fragmented and had a general lack of brand recognition, minimal advertising, and a low level of salesperson training. Leveraging the company’s deep metalworking expertise, garnered in its early years as a supplier to the automotive industry, Masco’s founder, Richard’s father Alex, solved an engineering problem that made one-handle faucets workable. When he couldn’t interest faucet companies in his patented innovation, Masco began making and selling the faucets itself.

Homeowners loved them, finding them a big improvement over traditional faucets that forced users to fiddle with hot and cold water separately. This extra functionality was particularly valued in kitchens where utility and maintenance-free operation were important. Not neglecting two-handle faucets, the company introduced a model with a new type of valve. This design, also patented, eliminated rubber washers, the major cause of faucet failure.

Masco went on to innovate in many other aspects of these new products, from basic manufacturing to distribution and marketing. It was the first to create brand recognition for a faucet with its Delta and Peerless brands. It was the first to introduce see-through packaging, to market faucets direct to the consumer through the do-it-yourself channel, and to advertise faucets on TV during the Olympics. In refashioning an industry of “me-too” products and boldly setting itself apart from others, Masco demonstrated that it was creative, able to apply traditional capabilities in new ways, and willing to take risks and make them pay off—abilities Richard Manoogian hoped would enable him to transform the furniture business.

NOW CONSIDER THE INDUSTRY

At the time Manoogian was weighing this decision, household furniture was a $14 billion business in the United States that didn’t make much money. With high transportation costs, low productivity, and eroding prices, it had about 2 percent annual growth, and return on sales, on average, was about 4 percent. There were more than 2,500 manufacturers, but 80 percent of sales came from only four hundred. Not all players were small, but most were, and many were family firms that had stuck it out through thick and thin, reluctant to leave the only livelihood their families had known for generations. Making matters worse, both sales and profits were cyclical and tied to broad economic factors such as new home starts and sales of existing homes.

Management in the industry was generally regarded as unsophisticated, and hadn’t made many significant changes in the previous fifty years. Wesley Collins, a furniture executive and trenchant observer of industry conditions, summed it up dramatically:

When everything else in our lives was changing, furniture stood its ground. While we put a man on the moon … furniture put another steak on the backyard grill and muttered, “My god, the price of oak went up again.”

When videotape put the home movie camera in the trash can forever, and tape cassettes put the plastic record-maker six feet under, and word processors put typewriters in the closet, and microwave popcorn killed the makers of popcorn makers … the furniture industry said, “Thanks, but we’ll stand pat.”

While we sat on our tuffets, the consumer forgot all about us. Our share of consumer expenditures slipped year after year. We lost over 40 percent of the retail furniture space in America, 25 percent of the retailers shut their doors, and department stores discontinued furniture right and left for products that gave them a better ratio of margin and turns per square foot.3

Collins went on to say that “the average tobacco chewer spends more for Levi Garrett Chewing Tobacco every year than he does for furniture.”

Most furniture purchases were discretionary and highly postponable, and, as Collins noted, there were many substitutes and lots of competition for the customer’s dollar. New innovations and designs were quickly knocked off by competitors, eliminating any advantage the innovators might have momentarily enjoyed.

Equally distressing, in the United States, there was little brand recognition in the industry. Customers didn’t know much about furniture and weren’t motivated enough to find out. There was little advertising and consumer research had shown that many American adults could not name a single furniture brand. Think for a minute: “What brand of sofa do you have in your living room?” When I pick an executive in the class at random and ask this question, the response is usually a startled look, a long moment of silence, and then, something like “Brown leather?” Everyone laughs, but when I open the question to the entire class, only a few hands go up and they’re inevitably executives from Europe. Yet when I ask how many of them know the brand of car their neighbors drive, virtually all hands go up. Yours probably would, too.

On top of its marketing challenges, the industry was riddled with inefficiencies, extreme product variety, and long lead times that frustrated customers. Buyers often received partial shipments; for example, a dining table might arrive weeks or months before the chairs that went with it.

The real issue, though, is not whether there are problems in the industry but what they mean. Are all these problems an opportunity for a courageous company with the right skills? Or are they red flags warning outsiders to stay away?

When I ask my executives whether they would take the plunge, most respond with a resounding “Yes!” They’re energized, not intimidated, by the challenges. Most say, in effect, “Where there’s challenge, there’s opportunity.” If it were an easy business, they say, some company would already have seized the opportunity: It would be much tougher to dislodge a strong leader than to gain ground in an industry like this where there are no big players, no Microsofts already established. “It’s a horse race,” someone once said, “and all the other horses are slow.”

Further, they note, the furniture industry is much like the faucet industry before Masco entered. The opportunity is a great fit with Masco’s manufacturing skills, its marketing savvy, and its strong management capabilities. It’s another chance for Masco to bring money, sophistication, and discipline to a fragmented, unsophisticated, and chaotic industry.

Opponents can’t get past how awful the furniture business is. They can’t imagine any company overcoming such huge hurdles. So the arguments go back and forth. Enthusiasm and a gung-ho spirit on one side struggle against caution and concern on the other. In one discussion, an exasperated proponent blurted out, “Look, this isn’t about being passive investors in some yet-to-be-invented furniture industry index fund. We’re going to be players in this game. We can make things happen. If Starbucks or Under Armour had listened to you naysayers, they wouldn’t have done anything!”

What’s your inclination at this point?

Usually when the time comes for a decision in my classes, “Do it” wins definitively, by at least a 2-to-1 margin.

So what, in fact, happened?

Masco did enter and in a bold way. Over two years, it bought Henredon (high-end furniture) for $300 million, Drexel Heritage (mid-price) for $275 million, and Lexington Furniture (low–middle) for $250 million. Combined, the revenues from the three made Masco the second-largest player in the U.S. furniture industry. It followed up by spending $500 million for Universal Furniture Limited (low end), which had manufacturing operations in ten countries on three continents and followed a ready-to-assemble concept—component parts were manufactured in low-cost countries and shipped in containers to five U.S. locations for assembly. Now Masco was both the largest furniture company in the world and one of the only firms with products spanning nearly every price point, a strategy that had worked well for the firm in faucets.

In total, Masco spent $1.5 billion acquiring ten companies and another $250 million upgrading their manufacturing facilities and investing in new marketing programs.

Presenting Manoogian with its Gold Award in the Building Materials Industry, the Wall Street Transcript cited his

imagination, foresight and strategic sense…. Manoogian has acquired low growth, mature products and become the dominant player in those product categories…. [H]is most recent set of acquisitions has been in the furniture industry. His strategy is to do to the furniture industry what he did to the faucet and kitchen cabinet industry….4

With this historical update, the classroom crackles with energy. Executives who had advocated for bold action nod their heads to one another or give each other high-fives and thumbs-up, pleased that they’ve nailed their first Harvard case. I hear little “told-you-so” comments directed at the naysayers, who sit in grim silence. Someone once even called across the room: “Don’t worry, Bob. One bad decision won’t ruin your reputation. We won’t hold it against you the rest of the program.”

But it doesn’t take long for those who opposed entry to speak up.

“But how did Masco do?”

“They bought great brand names,” says someone.

“But how did they do?”

“They’re number one in market share. What more do you want?”

“But did they make money?”

There, as it’s said, is the rub.

When I post Masco’s financial results, silence falls as people absorb the numbers. In a few seconds, there are whispered expletives around the room.

After thirty-two years of consecutive earnings growth, Masco’s net income fell 30 percent. Two years later, operating earnings from furniture came to $80 million on sales of $1.4 billion, an operating margin of 6 percent, versus 14 percent for the rest of the company. After many years of struggle, Masco announced its intentions to sell its furniture businesses, leading one analyst to comment:

In the spring, management will go on the road with restated financials illustrating their “core” earnings growth as if they never entered the furniture business. They hope to rebuild investor confidence in the old [pre-furniture] Masco … as a growth company by showing their track record and prospects in the building materials arena. Given the $2 billion furniture “mistake,” this won’t be easy.

In a sad postscript, Masco discovered that exiting the furniture business was much harder than entering it. After a number of deals fell through, it eventually succeeded in selling its furniture firms, at a loss of some $650 million.5 When it was all over, CEO Manoogian admitted, “The decision to go into the home furnishings business was probably one of the worst decisions I’ve made in 35 years.”6

It’s a sobering moment in the classroom. The executives there didn’t intend to open their careers at the Harvard Business School by losing hundreds of millions of dollars their first morning.

So, let me ask you again, as I do the managers in my class: “Are you the strategist your business needs?”

3

THE MYTH OF THE SUPER-MANAGER

AS A STRATEGIST, what can you learn from Masco’s foray into furniture and the support most executives give that ill-fated decision?

Even if you were undecided or skeptical about the furniture industry, I’m willing to bet that some part of you supported Masco’s move. No one respects timid, passive managers. Bold, visionary leaders who have the confidence to take their firms in exciting new directions are widely admired. Isn’t that a key part of strategy and leadership?

In truth, it is. But the confidence every good strategist needs can readily balloon into overconfidence. A belief that is unspoken but implied in much management thinking and writing today is that a highly competent manager can produce success in virtually any situation. One writer calls this “the sense of omnipotence that plagues American management, the belief that no event or situation is too complex or too unpredictable to be brought under management control.”1

I call this belief, when taken to its extreme, the myth of the super-manager. It seems to come naturally to many successful entrepreneurs and senior managers who see themselves as action-oriented problem solvers, confident doers for whom difficulties are daunting but solvable challenges. I see it behind Masco’s leap into furniture manufacturing and behind executives’ choice of the same path every time I teach the case. Confidence matters. But there’s much more to strategy and leadership than a steadfast belief that a daring vision backed by good management can overcome virtually all obstacles. Without the rest of it, “bold” too often becomes “reckless.”

Look at what such thinking did to Masco. Operating profitability dropped to half its historical average, and the firm’s stock price was lower when it left the furniture industry than when it entered ten years earlier. And money was only part of the cost. Where Wall Street had spoken of Masco as a “Master of the Mundane,” it began to speak of the company’s “past glory” and “bitter shareholders.”2 The company lost momentum as its leaders spent years distracted by a massive venture that ultimately failed.

For Masco, its move into furniture was a defining moment, but not a positive one. A legacy built over decades was shattered, an affirmation of a well-known Warren Buffett maxim: “It takes twenty years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it.” All because the strategist got this one choice wrong.

What happened?

Your instinct, like most managers’, is probably to seek the answer by looking at Masco itself and its leaders. Surely, the ultimate fault lies there. But to get the full picture, you must look as much outside as inside the firm.

Here is a first clue.

As our faculty team was preparing to teach the case for the first time, a colleague, the most senior in the room, said, “Wait a minute. This story sounds very familiar.” He left the meeting and went back to his office files. There he found “Mengel Company (A),” a case so old it was typed on onionskin paper.

Set in 1946, the Mengel case describes the firm’s plans to revolutionize the highly fragmented furniture industry. Mengel’s bold idea? Build scale, gain efficiencies by leveraging its manufacturing skills, and establish brand identity. To do this, it would buck industry practice and spend $500,000 on national advertising to “make the average consumer style-conscious” and build its “Permanized” brand name.3 I had never heard of Mengel, but with an eerie sense of déjà vu, I wondered if Masco’s leaders had known about them.

My own research in the industry led to the following list. What do you think these seemingly disparate companies have in common?

Consolidated Foods

Champion International

Mead

General Housewares

Ludlow

Intermark

Georgia Pacific

Beatrice Foods

Scott Paper

Burlington Industries

Gulf + Western

Like Mengel and Masco, these are all companies that tried and failed to find fortune in furniture manufacturing.

Most were regarded as well-run companies. Like Masco, they considered a fragmented, chaotic industry to be an opportunity for good managers to apply their skills. With great expectations and high hopes of success, they all jumped in with the intention of reshaping the industry through the infusion of “professional management.” Years later, they all left.

UNDERSTANDING THE FORCES

Most executives find this list both revealing and disconcerting. These were companies with considerable track records, yet they all failed in the same endeavor. Was there something problematic about the endeavor itself? Was something at work in the furniture industry that was outside the control of these companies and their leaders?

Here’s another clue.

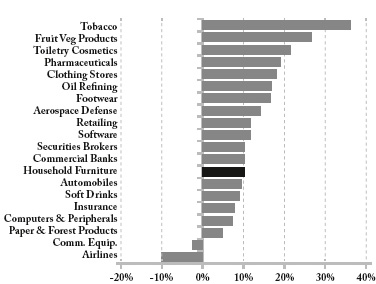

Look at the chart on Relative Industry Profitability. It shows the average return on equity for twenty industries over the twenty-year period from 1990 to 2010. The chart was compiled from Standard & Poor’s and Compustat databases that include data on all companies that traded on U.S. stock exchanges.

Relative Industry Profitability: 1990–2010 Return on Equity

Are you surprised by how much profitability varies by industry? Compare Tobacco companies at 36.1 percent average annual return on equity—which means leading firms in the industry do even better—with Airlines at -10 percent or Commercial Equipment at -2 percent.

In my experience, most executives understand that average profitability will differ from industry to industry, but the scale of variation often comes as a surprise. Annual average returns in the most profitable industries are well more than double those in median industries, and more than four or five times those at the bottom of the distribution. Researchers have found similar differences in other countries, in both advanced and emerging economies.4

Are these vast differences from industry to industry caused by random variation? It’s not likely—they’re too large and too consistent. Do some types of businesses attract great managers while others attract only poor ones? Sometimes, but not enough to account for the differences.

In fact, these variations are caused by economic forces that shape each industry’s competitive landscape differently.5 As Michael Porter has shown, some of these relate to the nature of rivalry within the industry itself; others have to do with the balance of power between the industry and its suppliers and customers, substitute products, and potential new entrants. Sometimes the forces are fierce and lead to low levels of industry profitability; other times they’re relatively benign and set the scene for much more profitable outcomes.

The collective impact of these forces on the profitability of individual firms, and, in turn, on industries in which they operate, is called the industry effect. You may be surprised to learn that some and perhaps much of your company’s performance is determined by such forces.6

These competitive forces are beyond the control of most individual companies and their managers. They’re what you inherit, a reality that you have to deal with. It’s not that a firm can never change them, but in most cases it’s very difficult to do. The strategist’s first job is to understand them and how they affect the playing field where competition takes place.

MAKING THE DISTINCTIONS

As suggested by the above chart, industries can be arrayed along a continuum extending from “Unattractive” to “Attractive,” where attractiveness refers to the degree to which industry competitive forces restrict, allow, or even foster firm profitability. The table below identifies the most important of these economic forces and characterizes what they probably would be like in industries at the bounds of such a continuum.7

Unattractive………………to AttractiveHigh. Many homogeneous competitors and homogeneous products. Innovations quickly copied. Slow growth. Excess capacity. Price competition.Rivalry among firmsLow. One or a few dominant, differentiated players. Unique products. Strong brand identities. Rapid industry growth. Shortage of capacity.High. Industry is dependent on a few, concentrated suppliers producing unique products, and Industry is not important source of profitability to suppliers.Power of suppliersLow. Many suppliers producing homogeneous products. Price competition and plentiful supply make it easy to procure supplies at reasonable cost.High. Customers have lots of choice among similar products. Low levels of brand awareness. Low switching costs. Low levels of emotional involvement with purchase.Power of customersLow. Products are scarce, highly differentiated, and important to customers’ well-being. Customers have limited choice. Brands are strong.Low. Industry is easy to enter and sometimes difficult to exit, creating excess capacity. Strategies of existing competitors can be easily replicated or surpassed. Entry requires low levels of capital, modest scale, and no scarce or specialized resources.Barriers to entry and exitHigh. It is difficult or not economical for new firms to enter your industry. Entry requires economies of scale, product differentiation, high capital investment, regulatory approval, or accumulation of special expertise or experience.High. Wide variety of compelling substitute products are available that meet customers’ needs at attractive relative prices.Availability of substitute productsLow. Customers have few or no choices of alternative products that could meet their needs at comparable prices.