Полная версия

The Spirit of London

Then I heard that the Live Sites, the special spectator zones we had created in Hyde Park and Victoria Park, were not always full. Where was everybody?

At one point I turned to my Olympic Adviser Neale Coleman, and said, ‘It feels like we are giving the biggest party in the world, and no one is showing up.’

‘Don’t worry,’ he said. ‘All Olympics are like this in the first few days. It will build.’

In an attempt to drum up custom for the Victoria Park live site, I went out there to launch the zipwire. During the preparations for the Games I had insisted that we must have zipwires in the parks, even though Neale said that his experience from the Vancouver Winter Olympics was that they were more trouble than they were worth. I felt honour bound to give it a go.

When we got to Victoria Park I was slightly unnerved to find a Health and Safety Officer from Tower Hamlets was just finishing his checks, and it was proposed that I should be the first to launch myself into space.

‘Are you sure you shouldn’t try it?’ I asked one of the fellows who seemed to be running it.

‘No, no,’ he said modestly. ‘We don’t want to spoil your photo.’

The thing was a lot higher and a lot scarier than I had expected, but there was nothing for it. Waving a couple of plastic Union Jacks I lurched off the tower rather fast, and immediately found myself spinning round so that I couldn’t see where I was going. I shot over knots of people in the park and then came to rest some way short of my destination, and about 30 feet up. A crowd formed beneath me as people twigged that this wasn’t part of the plan. I tried diverting them with rousing remarks about how well our team was going to do against France and Australia. Their enjoyment of my position was growing, however, and there seemed no clear plan for getting me down.

The harness was starting to chafe, especially in the groin area.

‘Has anyone got a ladder?’ I asked.

No one had a ladder. At length I spotted my Special Branch personal protection officer, a nice chap called Carl. He had been seconded from his normal job of guarding Tony Blair, and was supposed – I reasoned – to rescue me from embarrassing predicaments.

‘Carl,’ I said, ‘is there anything you can do?’

Slowly he reached into his breast pocket, took out his mobile phone, aimed carefully, and took a picture of my dangling form … The only positive thing you could say about the episode is that at least we gave that zipwire some publicity.

But the truth is that nothing was really going to give the thing lift-off until we started winning gold medals, and they were nerve-wrackingly slow in coming. The great cyclist Mark Cavendish didn’t win his first road race on the Saturday, even though everyone told us that it was meant to be a cert. Then we didn’t seem to be doing quite as well in the pool as we had hoped, and though Becky Adlington swam heroically, she didn’t take gold, as she had in Beijing.

We seemed to be well behind France and Australia in the medals table. In fact we were languishing at about tenth or even twelfth – and the French president François Hollande came over to say something smug about how decent it was of Britain to roll out the red carpet for French athletes to win on.

And then in the middle of the first week, round about the time Bradley Wiggins won his gold in the cycling time trial, you could feel something shift in the general mood – a stirring in the noosphere.

Everyone was becoming transfixed by the sport – even people who had hitherto had no real interest in sport; and the people who were lucky enough to get into one of the venues were reporting the time of their lives. Seb Coe, Paul Deighton and the rest of Locog deserve credit for many things, but if one thing distinguished London from Beijing, it was the punter’s experience – your experience as a spectator.

A great deal of trouble was taken to manage you, psychologically, and to get you going. As you walked into the Olympic Park and other venues you were hailed cheerily by pink and magenta volunteers, some of them waving giant pink hands. They might chant a jovial slogan, or even sing some ditty they had made up themselves. And when you got to your seat, you didn’t just sit there. You were coaxed to enter into the spirit of the thing by energetic comperes. There was thudding music to go with the sport, and any longueur was accompanied by a Mexican wave – often led by the sporty young Royal Couple Kate and Wills, who seemed to be more or less everywhere. There was rhythmic clapping, to the tune of Queen’s ‘We Will Rock You’, with the entire crowd slapping their knees and then raising their arms like Aztec sun-worshippers.

If that didn’t shatter your inhibitions, you might be asked to mime playing the bongos for the bongo cam, or you might be asked to stand up and dance before a crowd of tens of thousands – or a vast global audience – or you might be asked to kiss your neighbour, male or female, friend or stranger, for the kisscam.

It was a drama in which you became personally involved, and you were allowed to get carried away because of the sense of occasion – that this was a once-in-a-lifetime transformation of the city that might never be repeated. Across London Locog had prepared the most astonishing scenery. Suppose you were in Horse Guards watching the Beach Volleyball. Let’s be honest, most of us had never watched the game before in our lives – I couldn’t have told you the rules, or how many players there are per side. But there we were, surrounded by the old Admiralty, by Downing Street and William Kent’s lovely clutch of eighteenth-century Portland stone buildings – and there in the middle was this thudding sandpit from Copacabana beach, with semi-naked people writhing around.

Each on its own was worth a look, but the sense of specialness was in the combination, the juxtaposition. That struck me as being different from other Olympics – this mixture of old and new that is the genius of London: a city which is never complete but where ancient buildings stealthily acquire gleaming modern neighbours or additions, the interest of each being intensified by proximity to the other.

You went to Greenwich Park and you saw the rear ends of horses bucking high into the sky against a background of Wren’s Hospital, and the towers of Canary Wharf behind Wren’s masterpiece – and the horses jumped to the tune of Van Halen’s ‘Jump’. When the time came at the end of the first week to begin the athletics it was clear that the stadium was a masterpiece of design. Even in the morning sessions it appeared to be (and was) bursting with humanity, and most athletes said they had never heard a noise like it.

With that psychological conditioning, and in that environment, most members of the public were more than ready to enjoy themselves – and then the athletes started winning: the British athletes of whom some of us, in our ignorant pessimism, had begun to despair.

The first golds were taken by the women rowers, Heather Stanning and Helen Glover; then there was Bradley Wiggins; then a farm boy from Dorset defeated the world at shooting – and then it seemed there was nothing Team GB couldn’t win. We weren’t just winning in the kit-intensive sports like cycling, sailing, riding, rowing – all the sports that involve sitting down, as the old joke puts it. British athletes were winning at running and jumping as well – activities which don’t require that much expensive equipment, and where British athletes were taking on the best of the rest of the seven billion people in the world, and doing even better.

There can be no doubt that it was this patriotic feeling – massive group engagement with some individual’s struggle and achievement – that drove the crowd nuts with joy. At the Stadium, the Velodrome, the Aquatics Centre, the vocal support was like a blast wave or sonic shock that seemed to send British athletes faster than the rest. At Eton Dorney the noise from the rowing crowd was like the last trump.

The spectators became deeply engaged in these contests, and often it wasn’t just the athletes who were allowed to shed a tear – win or lose – at the end of their performance. Sometimes even BBC presenters permitted their lower lip to wobble, and sometimes large sections of the audience were in absolute floods. Who says the British are not an emotional people? It became a kind of blubberama.

Soon it became noticeable that the emotional commitment was being extended not just to British athletes, but to all participants. Wild applause greeted any act of sportsmanship, any recovery from a setback. We cheered athletes from France, from Australia, and even Mitt Romney was redeemed (after some incautious remarks about London’s state of readiness) when it was discovered that his wife part-owned a horse in the dressage. A sort of euphoria took hold of the population – as though we had been crop-dusted with endorphins, or Thames Water had added serotonin to the supply. It spread out from the venues via the millions of people watching on TV. In towns and villages across the country pillar boxes were being painted gold in honour of the victorious athletes, and after four years of economic gloom, and exactly a year after riots had swept London and other British cities, a mysterious sense of well-being seemed to descend upon the nation – or at least on the large numbers who got the bug. Sociologists or anthropologists will be able to tell you what was going on, but it struck me as a benign mental contagion, a bit like the sentimental affliction that hit us after the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, except that this time it was positive.

People would start up conversations on the Tube – and no one assumed they were mad. One woman turned to a City Hall official, without knowing who he was, and said: ‘I want to know who I can write to, to thank for it all.’ It became obvious, in short, that we had a monster hit on our hands, far bigger than any of us had expected.

The things that were supposed to go wrong had not gone wrong. The transport systems all worked fine. More people hired Barclays bikes than ever before. The cable car took more than a million on high, to see the sights of East London, including Arnold Schwarzenegger, who pronounced the view of Canning Town ‘very nice’. The Tube carried record numbers of people – about 4.5 million per day – with more or less metronomic efficiency. The Jubilee Line worked so well, in fact, that members of the ‘Olympic Family’ abandoned their claims to the so-called Zil Lanes and took public transport with the rest of us.

Athletes flashed their medals at fellow passengers. The Rwandan team were seen at a bus stop. When David Cameron took the Tube he was thanked (very properly) by a member of the public for his role in helping to make it go faster. The IOC president Jacques Rogge took the Docklands Light Railway and pronounced it excellent. London transport got every single athlete, politician, bureaucrat and journalist to his or her destination on time. More or less.

Having given us all such a fright, the G4S staff started to turn up in droves. The security operation was masterminded by thousands of military personnel and they all – including the police – did such an effective job that I didn’t hear of a single serious delay in getting into the venues.

As for the weather, it performed a complete somersault, and for more than two weeks it remained good to fair: maybe a bit overcast at times, but perfect for a garden fete. It turned out that the tourists had not entirely fled London, and those that came spent more than in previous years. Crime fell by a further five per cent.

And the things that were meant to go right went spectacularly right. It helped that the Team GB athletes were so nice and well-balanced. Many commentators drew the contrast between the modesty and work ethic of these relative unknowns, and the behaviour of professional footballers.

It also helped that the quality of the sport – not just the British contribution – was superb. Good old Usain Bolt. He not only came to London and ran 100m in the second fastest time in history. He ran faster than he had in Beijing. Then he won the 200m as well, becoming – arguably – the greatest athlete in history. Then he and his Jamaican colleagues went on to obliterate the 4 × 100m world record. He fully deserved his night of relaxation, or whatever it was, with those Swedish volleyball players. London set 27 world records across the board, from weightlifting to cycling to the women’s 4 × 100m sprint to David Rudisha’s astounding 1 minute 40 in the 800m; and that was important. This Olympics wasn’t just a big moment for Britain. It was a big event for the world, a moment when humanity collectively pushed out its boundaries.

But elite sport is for the very few. Only a tiny fraction of the top one per cent will have the talent and the application to become Olympic athletes, let alone medallists. The ethic of the Games is stark, Homeric: an all-or-nothing competition that ends in the glory of success or the dejection of defeat. And so for many people the true spirit of the London Games was shown not just by the athletes, but by the volunteers – the 70,000 Locog Gamesmakers, the 8,000 Team London Ambassadors.

They were there to show that everyone could participate, that 2012 belonged to us all. They democratised the Games. They had something of the Butlin’s Redcoats in their chirpiness, and they steadily acquired their own heroic status in the minds of the public, and for many of them – as they repeatedly told me – it was the best and most exciting thing they had done in their lives (and the same is true of many of the rest of us). They may have temporarily mothballed the pink and magenta livery, but many of them will be hoping to do something like it again.

By the end of the Paralympics, it was as if nothing could go wrong; or rather, people no longer seemed to mind it, whatever went wrong. We took the Javelin home after the Paralympic Opening Ceremony. This turned out to be a mistake, since the service was reduced, and we waited for about two and a half hours in a crowd of thousands. Under normal circumstances I reckon I would have been lynched. But no: the mood was so outstandingly charitable that I found myself being thanked.

One day towards the end of the Paralympics I was walking through the Park, and thinking that it was even more packed than it had been during the Olympics. The sun shone on happy crowds as they thronged over the bridges. Families played in flower-filled meadows. It was like some ancient vision of Elysium, and I thought, look at this lot.

Talk about value for money.

By the end of the Games we had paid for major improvements to London transport; we had built thousands of new homes; opened the biggest new green park in Britain for 150 years and were well on the way to regenerating large parts of East London. We had beamed positive images of Britain around the world and filled people with a general sense of togetherness and love-your-neighbour. What else is politics for? If you reckon that the £9.3 billion has been spent over the best part of ten years, it must rate as one of the best investments by any government ever.

We learned all sorts of things about London and Britain, truths that we had half-forgotten. After the shambles of the Dome in 2000, we discovered that we could after all put on a great show, and deliver a big and difficult project – and hosting the Olympics is the single biggest logistical feat you can ask any country to pull off, short of going to war. That is an important lesson for all the cynics who wonder whether we have the capacity to deliver the new infrastructure projects the country so badly needs (a new hub airport springs to mind, or a new generation of nuclear power stations).

We saw the importance of making the public and private sector work together, and the Games were a triumph of collaboration between some very bright officials and some of the cleverest businessmen I have ever met.

We saw how this country and much of the world has changed for the better, in our lifetimes. Saudi Arabia fielded their first female athlete. British women took the centre stage, and in some ways eclipsed the men. ‘Jess Ennis is so cool,’ I heard a thirteen-year-old boy say. He didn’t just mean that he fancied her, though maybe he did. He meant that she was remarkable, admirable, a role model. That is a development.

The Paralympics were by common consent the best and most dramatic ever staged, with their own stars and record-breakers. It would not have been possible, in my childhood forty years ago, to imagine huge crowds of Londoners cheering with passionate sincerity and acclaim at a contest between athletes with prosthetic limbs. That is also a development. Yes, I am sure that Tanni Grey-Thompson would tell me there is still a long way to go, but progress has been made.

In the exuberance and generosity of the reaction, the Games also brought out something of the character of London. It is in many ways an English city. It has quintessentially English pubs and gardens and heavenly parks. It has whistling builders and fatalistic-looking passengers sitting on top of heaving red buses; and suburban shopping arcades with garish vinyl signs advertising curry or fried chicken; and softly swearing taxi drivers; and church bells that still toll on a Sunday morning from 150 beautiful steeples that rise over the familiar granite and yorkstone pavements spangled with rain and vomit from the night before.

London is the capital of England, of Britain, of the United Kingdom. But the Olympics reminded us that it is also a global city.

When those teams of athletes arrived this year, there were 50 nations who had home teams in London of more than 10,000 each. There is no other city like that, save possibly New York. In that sense the Games were a metaphor – or an extension – of the function London has played over the last few centuries: the arena, the stadium, the venue where talented people can come and compete, and make their name.

In the enthusiastic response of that London crowd – the vehement (and amazingly unaggressive) British patriotism that was shown by people from all races and backgrounds, we saw how the city takes people in and makes them its own. This is the sign of a confident urban culture, to take people from all over the world and make them Londoners, in vocabulary, accent, loyalty and even in their sense of humour. That is the spirit of London.

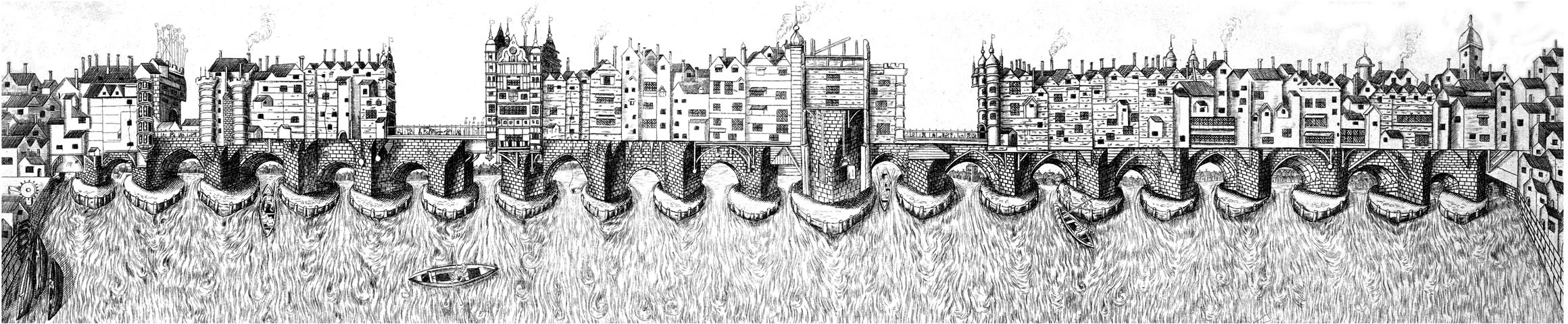

London Bridge

Still they come, surging towards me across the bridge.

On they march in sun, wind, rain, snow and sleet. Almost every morning I cycle past them in rank after heaving rank as they emerge from London Bridge station and tramp tramp tramp up and along the broad 239-metre pavement that leads over the river and towards their places of work.

It feels as if I am reviewing an honourable regiment of yomping commuters, and as I pass them down the bus-rutted tarmac there is the occasional eyes left moment and I will be greeted with a smile or perhaps a cheery four-letter cry.

Sometimes they are on the phone, or talking to their neighbours, or checking their texts. A few of them may glance at the scene, which is certainly worth a glance: on their left the glistening turrets of the City, on the right the white Norman keep, the guns of HMS Belfast and the mad castellations of Tower Bridge, and beneath them the powerful swirling eddies of the river that seems to be green or brown depending on the time of day. Mainly, however, they have their mouths set and eyes with that blank and inward look of people who have done the bus or the Tube or the overground train and are steeling themselves for the day ahead.

This was the sight, you remember, that filled TS Eliot with horror. A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many, reported the sensitive banker-turned-poet. I had not thought death had undone so many, he moaned; and yet ninety years after Eliot freaked out the tide of humanity is fuller than ever. When I pass that pavement at off-peak times I can see that it is pale and worn from the pounding, and that not even the chewing gum can survive the wildebeest tread.

The crowd has changed since Eliot had his moment of apocalypse. There are thousands of women on the march today, wearing trainers and carrying their heels in bags. The men have rucksacks instead of briefcases; no one is wearing a bowler hat and hardly anyone seems to be smoking a cigarette, let alone a pipe. But London’s commuters are still the same in their trudging purpose, and they come in numbers not seen before.

London’s buses are carrying more people than at any time in history. The Tube is travelling more miles than ever, and more people are riding on the trains. It would be nice to reveal that people are ditching their cars in favour of public transport; and yet the paradox is that private motor vehicle transport is also increasing, and cycling has gone up 15 per cent in one year.

As we look back at the last twenty years of the information technology revolution, there is one confident prediction that has not come true.

They said we would all be sitting in our kitchens in Dorking or Dorset and ‘telecottaging’ down the ‘information superhighway’. Video link-ups, we were told, would make meetings unnecessary. What tosh.

Whatever we may think they ‘need’ to do, people want to see other people up close. I leave it to the anthropologists to come up with the detailed analysis, but you only have to try a week of ‘working from home’ to know it is not all it’s cracked up to be.

You soon get gloomy from making cups of coffee and surfing the Internet and going to hack at that piece of cheese in the fridge. And then there are some profounder reasons for this obstinate human desire to be snuffling round each other at the water cooler. As the Harvard economist Edward Glaeser has demonstrated, the move to the city is as rational in the information revolution as it was in the Industrial Revolution.

By the time I get to cycle home, most of the morning crowds have tramped the other way. Like some gigantic undersea coelenterate, London has completed its spectacular daily act of respiration – sucking in millions of commuters from 7 am to 9 am, and then efficiently expelling them back to the suburbs and the Home Counties from 5 pm to 7 pm. But the drift home is more staggered. There are pubs, clubs and bars to be visited and as I watch the crowds of drinkers on the pavements – knots of people dissolving and reforming in a slow minuet – I can see why the city beats the countryside hands down. It’s the sheer range of opportunity.

You can exchange Dante/Beatrice glances on the Tube escalator; you can spill someone else’s latte and offer to buy them another; you can apologise when they tread on your toe, or you can get your dog lead tangled in theirs, or you can just collide with them on the pavement. You can even use the personal dating services in the evening paper or (I imagine this still goes on) you can offer to buy them a drink. These are some of the mating strategies of our species; but they have statistically a far higher likelihood of success in a city, because it is in the city where there are the numbers and the choice of potential mates – and the penalty for failure is much lower.

The metropolis is like a vast multinational reactor where Mr Quark and Miss Neutrino are moving the fastest and bumping into each other with the most exciting results. This is not just a question of romance or reproduction. It is about ideas. It is about the cross-pollination that is more likely to take place with a whole superswarm of bees rather than a few isolated hives.

You would expect me to say this, and I must of course acknowledge that many great cities can make all kinds of claims to primacy, but at a moment when it is perhaps excessively fashionable to be gloomy about Western civilisation I would tentatively suggest that London is just about the most culturally, technologically, politically and linguistically influential city of the last five hundred years. In fact, I don’t think even the Mayors of Paris, New York, Moscow, Berlin, Madrid, Tokyo, Beijing or Amsterdam would quibble when I say that London is – after Athens and Rome – the third most programmatic city in history.