Полная версия

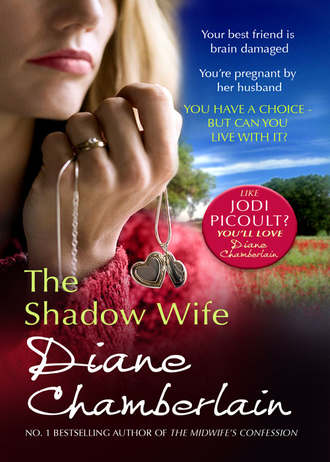

The Shadow Wife

But beneath her worry and fear and uncertainty was a vague, yet alluring, hint of joy.

The maternity unit looked entirely different to Joelle when she stepped inside the Women’s Wing of Silas Memorial Hospital the following day.

As she did every morning, she walked toward the nurses’ station, past the open doors of the patients’ rooms. This morning, though, the sight of the women walking slowly through the corridor as they healed and the cries of babies from the rooms held a different meaning for her. In mere months, she could be one of these women. One of the crying, hungry, beautiful babies could be hers.

She found Serena Marquez at the nurses’ station and held out her arms to the head nurse.

“You’re back!” Joelle said, giving her a hug. “Do you have pictures?”

“Does she have pictures,” one of the other nurses said, wearing a grin. “I think she spent her entire maternity leave with a camera glued to her face. Hope you have all morning, Joelle.”

Joelle leaned on the counter, her hands outstretched. “Let’s see them,” she said to Serena.

“We should talk about your referrals first.” Serena was beaming, clearly anxious to hand pictures of her little boy over to an apt audience, but motioning instead toward the forms in Joelle’s hands.

Joelle took a seat on one of the stools, then read aloud the names on the forms, and Serena pulled the plastic binders containing each patient’s medical record from the turntable on the desk. Joelle studied the referrals: two requests for help at home for a couple of single mothers, one case of questionable bonding between mother and baby, one baby born to a cocaine addict, one father denying paternity, one stillbirth. It was a typical batch of referrals for the maternity unit, including the stillbirth. In Joelle’s line of work, where she was invited to see only the problems and rarely the joy, dealing with the family of a stillborn infant was all in a day’s work. It was never easy, though, and today in particular, when the pink and blue lines were still very much in her mind, she winced as she read through the woman’s chart. This was the woman’s second stillborn baby. She looked at Serena. “How is she doing?” Joelle asked.

“Not too well,” Serena said. “Nice lady. Thirty-five. They lost the first baby and had been trying hard for this one, apparently.”

Thirty-five. If she were to have this baby, she, too, would be thirty-five when it was born.

“Why is she losing them?” Joelle asked.

Serena shook her head. “Unknown cause.”

“Poor thing,” Joelle said. “To go through this twice, with no answers …” She asked Serena a few more questions about the woman and her family, then reached once again for the pictures of the head nurse’s baby. She glanced from the pictures to Serena, as she sorted through them. Serena’s cheeks were pink, and although she had not lost all the weight she’d gained during her pregnancy, there was a radiance about her that Joelle envied. The nurse was twenty-eight, and this had been her first child. Joelle wondered if, while Serena was pregnant, she, too, had experienced the maternity unit in a different way. She didn’t dare ask.

She made the mother of the stillborn infant her first stop, noticing as soon as she walked into the patient’s room that the woman looked a little like her. She had long, thick dark hair with deep bangs and was more cute than pretty. She looked more like thirty than thirty-five. Her husband sat at his wife’s bedside, holding her hand, and her mother sat in a chair at the foot of the bed, her hand resting on her daughter’s leg through the bedclothes. There was love in the room, an almost palpable sense of caring between the husband and his wife. That was the difference between herself and this patient, she thought. This woman was married, with a husband who obviously loved her.

“How could this happen again?” the woman’s mother asked, a question Joelle could not answer. She rarely had answers in these situations. All she had was the training and experience to anticipate what the family was feeling, and the skill to provide comfort or support. She spoke with them for quite a while, letting them talk and cry over their loss, then asked them if they wanted to see their baby.

“No,” the woman said emphatically. “We saw our last baby. We held her and …” She began to cry. “I can’t go through it again. I don’t want to see this one.”

Joelle nodded. Ordinarily, she might try to persuade the parents to see their infant, but in this case, she was willing to accept their decision. They knew what they were turning down. She didn’t blame them, yet she would stop back later, in case they changed their minds.

She left the room after half an hour, knowing that this particular woman, who looked like her and who had tried hard to get pregnant, would stay with her. Two babies, loved and lost. Joelle thought of the tiny life growing inside her and admitted to herself what she had known since seeing the pink line in the middle of the night: she could not abort her baby.

The hospital cafeteria had been remodeled the previous year with mauve walls and huge windows that looked out on Silas Memorial’s parklike courtyard. Joelle stood in the entrance to the dining area, holding her tray, trying to convince herself that the scent of the liver and onions on her plate was tantalizing rather than revolting. She’d selected the liver, along with spinach and a glass of milk, for her lunch. She was eating for her baby, the baby she was going to have, no matter what the cost. Searching the tables for her two fellow social workers, she spotted the men near the windows and walked toward them.

“Hi, guys,” she said, setting her tray on the table and taking a seat adjacent to Paul and across the table from Liam. The three of them ate together nearly every day, whenever their schedules would allow it.

“What’s with the liver?” Paul grimaced in the direction of her tray.

“I don’t know,” she said. “Just felt like a change.” Paul Garland handled the pediatric and AIDS units. He’d only worked at Silas Memorial for a year, but he’d had previous hospital experience and had fit in well. Liam Sommers had been the social worker for the AIDS unit at the time of Paul’s arrival, and Paul had begged to take over that assignment with such fervor that Liam had agreed. Joelle and Liam had speculated that Paul was gay. He was a stunningly handsome man, always neatly tailored, with stylishly short black hair, green eyes and a sexy crooked smile, and everyone knew he had once modeled for a department-store chain. But they soon realized, especially after meeting Paul’s fiancée, that he was quite straight, and that his interest in AIDS patients was born of his compassion for them, nothing more.

Liam, who covered the emergency room, as well as the oncology and cardiac units, was Paul’s opposite, at least physically. His hair was light brown and on the long side. It had a bit of wave to it, and it grazed the top of his ears and the nape of his neck in a way that Joelle found appealing. His eyes were a pale, pale blue. The few times Joelle had seen Liam in a suit, he’d looked almost silly; this was a man cut out for T-shirts, maybe a Hawaiian-print shirt or plaid flannel in cooler weather. He had a warm, white smile that had been all but absent this past year. She missed seeing it across the table from her at lunch.

Since starting to work at Silas Memorial nearly ten years earlier, Joelle’s assignments in the hospital had been the Women’s Wing and general surgery, but she and Paul and Liam covered for one another as needed. When one of them had too much on his or her plate, the other two would pitch in, so they always tried to keep one another abreast of their cases.

“How is your day going?” Liam asked her as she took a bite of liver. It was not too bad with the onions to mask the flavor. “Okay, except for a stillbirth. It’s their second.” “Second child or second stillbirth?” Paul asked. “Second stillbirth. With no apparent cause.” She ran her fork through the dull green, obviously canned, spinach. “It’s gotten to me, for some reason.” She wished she could tell them, but knew it would be a long time before she revealed her pregnancy to anyone. She would hold out as long as she could before letting the rest of the world in on the unplanned, and possibly reckless, choice she had made.

“Why do you think?” Paul asked. She shrugged, cutting another piece of liver. “Because you struggled with fertility yourself,” Liam offered. “Of course it gets to you.”

“That’s probably it,” she said, willing to allow Liam that explanation. “And what are you two dealing with today?”

The men took turns discussing their cases, and Joelle listened as she forced down the liver, bit by bit. The three of them used to be jocular with one another, but a pall had settled over them a little more than a year ago, when Liam’s wife, Mara, suffered an aneurysm while giving birth to their first child. In the days following the birth, Silas Memorial’s nurses and doctors, various technicians and even the custodial staff, would come up to Liam during lunch to ask him how his wife was doing. Gradually, their concerned questions slowed, then stopped, as word got around that Mara would never recover. Only people very close to Liam bothered to ask anymore. Mara had been moved from the hospital to a rehab center, then soon after into a nursing home as it was determined that rehabilitation wouldn’t help her. They had found an excellent nursing home for her; Liam and Joelle and Paul certainly knew which homes were the best in the area. But sometimes Joelle wondered if it mattered. Although Mara seemed strangely content, even joyous at times, a phenomenon that her doctors described as euphoria brought on by brain damage, she didn’t know that the little boy who visited her with Liam was her son. Joelle, herself, stopped by the nursing home at least once a week, and although Mara was full of smiles and looked delighted to see her, she didn’t seem to understand that Joelle had once been her friend. Nor did she recognize her own mother. She welcomed everyone, from her child to the electrician, into her room with equal pleasure.

She knew Liam, though. It was obvious in the way she lit up when he appeared in her doorway at the nursing home, and in the sounds she made, like a puppy whose owner had returned after an absence. Joelle wasn’t certain if Mara’s surprising good cheer made it easier or harder for those who loved her to cope with her condition. Mara had never been the sort of woman one would describe as perpetually cheerful, and her simple happiness made her seem like a stranger. It had been only in the last few months that Joelle could drive away from the nursing home after a visit without crying in her car.

Mara had been Joelle’s closest friend for years. A psychiatrist in private practice, Mara had specialized in psychological problems related to pregnancy and childbirth, and Joelle would bring her in as a consultant from time to time on her hospital cases. She’d been drawn to Mara the instant she met her. Two years older than Joelle, Mara had worn her straight dark hair to her shoulders, and her nearly black eyes were intense against her fair skin. She was a remarkable mixture of qualities and interests: young doctor, novice folk musician, churchgoing Roman Catholic, yoga instructor and avid runner who had participated in three marathons and was fluent in several languages. Although Mara was the consummate professional while at work, once she and Joelle were alone, she slipped easily into girl talk, the sort of sharing of intimacies that created a treasured and unbreakable bond. It was Joelle who had introduced Mara to Liam, after he started working at Silas Memorial, and she couldn’t have been more pleased when those two people she cared about began to love each other.

Lord, she missed Mara! She had no one to turn to with the dilemma she was facing, no one she could safely tell about her pregnancy. Least of all the baby’s father, even though he was sitting right across the table from her.

2

AT FIVE O’CLOCK,LIAM SAID GOOD-NIGHT TO THE STAFF IN THE emergency room and left the hospital. It had been a long day; his pager had gone off so often for the E.R. that he’d had little time for oncology or cardiology, and he would have to spend more time in those units tomorrow. To make matters worse, this week was his turn to be on call, so he wasn’t able to turn off his pager as he walked across the employee parking lot to his car. He alternated nighttime and weekend coverage with Joelle and Paul. The overtime pay was decent, but the “every third week” schedule had just about done him in this year. He’d been trying to persuade management to hire another social worker, someone who would only cover evenings and weekends, but there was no money for that. Joelle had volunteered to do an extra week on call every month to help him out, but he didn’t think that was fair, even though he had a year-old child to take care of and she did not.

On a couple of occasions, he’d called Joelle, either to take a middle-of-the-night case at the hospital for him or to ask if she’d watch Sam while he took the case himself, but he wouldn’t be calling her anymore. As of two months ago, he’d felt unable to ask her for a favor or see her outside of work in any capacity, or—God forbid—be alone with her. It was okay when Paul was with them, but alone, he found himself unable to make eye contact with her, as though he was embarrassed or ashamed. And he was both.

So now, those dreaded middle-of-the-night E.R. calls meant that he had to awaken Sheila, Mara’s mother, and ask her to come over and stay with Sam while he went to the hospital. Sheila was a great sport, though. She lived less than a mile from Liam in a two-story house Mara had always called “the pink house” because of its cotton-candy color. The pink house was just a block from Monterey State Beach, where Sheila often took Sam, bundled up against the cool air, to watch the kites zig and zag through the sky. A widow who had retired several years earlier from the Monterey Institute of International Studies, where she’d taught Russian, Sheila took care of Sam every day while Liam was at work, and she never complained when he had to ask her to come at one or two in the morning, as well. She also, unfortunately, had to help Liam with his mortgage. Monterey housing was horrendously expensive, and without Mara’s handsome income from her psychiatric practice, he couldn’t possibly have kept his three-bedroom, cottage-style home. He was dependent on Sheila in many ways, which was both a blessing and a curse. Liam’s own family—his parents and older sister—lived three thousand miles away in Maryland. Although they kept in frequent touch with him, there was little they could do to help him financially.

He drove straight from Silas Memorial to the nursing home in Pacific Grove, a ten-minute ride in decent traffic. Once in the parking lot, he spotted Sheila and Sam sitting together on the concrete bench outside the entrance. He waved to them as he pulled into a parking space, a smile forming on his lips. He could actually feel the unfamiliar change in his face; his smile muscles were atrophying from disuse.

The grounds of the nursing home were beautifully landscaped and vibrantly green and alive. That was one of the reasons Liam had been drawn to this place, why he had selected it over the others. It was also cleaner and brighter inside, and he and Sheila and Joelle had eaten a meal there and found the food to be both palatable and nicely presented. He remembered those days of searching, of weighing the aesthetics of various homes, and thought of how naive the three of them had been. None of that mattered to Mara. Very little mattered to her anymore.

Liam walked up the pathway from the parking lot to the home, and Sam tottered toward him as he neared the bench. The cutest child on earth, Liam thought, not for the first time. Sam was small for his age, a doll-like fourteen-month-old little boy, with curly blond hair that was certain to darken as time wore on, and Mara’s dark eyes and fair skin, which would always need protection from the sun. Sam wore a constant smile. He had no idea that his birth had brought about such tragedy. Liam hoped that, somehow, he’d be able to protect his son from making that connection, at least until he was much, much older.

When he walked quickly like this, filled with excitement at seeing Liam, Sam looked as though he might topple over at any second. Sometimes he did, but this time he made it all the way to Liam without a hitch. Bending over to pick him up, Liam planted a kiss on his cheek, breathing in his scent—which was all too quickly changing from baby to little boy—before settling him into his arms. He knew Sam would only remain there for a moment. Sam loved his newfound skill of walking, and Liam missed the closeness of holding him for more than a minute at a time. It was going to be hard to let go of his son, bit by bit over the years, as his development demanded. There were days when Liam felt as though Sam was all he had left in the world.

“We had such a wonderful day,” Sheila said, standing up from the bench and brushing a lock of blond hair away from her face. The warm breeze blew it back again, along with a few other wayward strands. In the sunlight, Liam could see the subtle crow’s-feet at the corners of Sheila’s eyes, reminding him that she had turned sixty the week before. She’d had a face-lift at fifty-five, and while she was a stunning woman, her skin smooth and barely lined, there was something in her face that told her age. Only in the last year had he noticed that. Everyone involved in Mara’s care had aged: Sheila, Joelle, Mara, himself. This year had stolen something from each of them.

“Oh, yeah?” Liam sat down on the bench. “What did you do today, Sam?” he asked, and Sam squirmed to get out of his father’s arms and back on the sidewalk without answering. Sam was not very verbal yet, still speaking in one- or two-word sentences, but ever since discovering his legs, he’d been impossible to keep still. Liam didn’t know how Sheila kept up with him all day.

Liam watched his son as he explored one of the light fixtures that lined the sidewalk near the ground. Sam banged it with the flat of his hand, as though trying to make it do something, and Liam turned his attention to his mother-in-law.

“How are you doing, Sheila?” he asked her, and she smiled.

“He’s my world, Liam,” she said, nodding toward Sam. “He’s the joy that helps me deal with the sorrow. I don’t know what I would do without him.”

Liam nodded. He understood completely. Standing up, he held his hand out to Sam. “Let’s go see Mom,” he said, and Sam tottered over to him, slipping his tiny hand into Liam’s.

The foyer was bright from two huge skylights overhead, and the place smelled truly clean without being antiseptic. It was actually Joelle who had first recommended this nursing home to him. He remembered her sitting at the desk in her tiny office, tears running down her cheeks, as she called around looking for the best place for Mara. It had been a terrible day, a giving-up day. After four months in the intensive-care unit of the hospital, a short coma, two surgeries and a fruitless stint in rehab, Mara’s doctors had said they should begin looking for a home. He’d felt paralyzed at first, and Joelle had taken over. There was rarely a day that he walked into this building without thinking of her with silent gratitude.

Mara’s room was at the end of the hallway, where he had insisted she be placed because the room possessed two huge windows, one of which overlooked the beautiful green courtyard with its white gazebo. He had visited Mara every single day since she’d been moved here nine months earlier—except for the day after he and Joelle had slept together. He couldn’t bring himself to visit Mara that day, to see the innocent wonder in her face and experience her joy at seeing him. He’d been filled with guilt and anguish that he and Joelle had crossed that line. He was disgusted with himself for wanting it to happen, for allowing his heart and body to overrule his mind.

Mara began to make her “happy sounds,” which Joelle affectionately called her puppy squeals, as soon as the three of them stepped into her room, and Liam immediately broke into the upbeat voice he had mastered for these visits.

“Hi, Mara!” he said as he walked toward her bed. He bent over to kiss her on the lips, then lifted Sam and put him on the edge of the bed.

“We should get her up in the chair,” Sheila said, but an aide passing by in the corridor must have overheard her, because she peeked around the doorway.

“She was up for a while this afternoon,” she said. “It’s better if she stays in bed for your visit today.”

Liam was secretly glad. Getting Mara from the bed to the chair was an ordeal, and he felt certain she didn’t like the manhandling it necessitated, because she would lose her smile during the process. Mara could only control her head and her right arm. She couldn’t speak, and her brilliant mind, or at least most of it, was gone.

“Okay,” Liam said. “We’ll let her rest in bed while we’re here.”

Mara’s smile widened, as though she understood him. He still felt love from her. She couldn’t express it except with her smile and her squeals and the light in her eyes when he walked into her room, but he knew it was there, and he felt both honored and burdened by that fact. Not even Sheila, her own mother, could elicit that demonstration of recognition from her. Nor could Joelle, who Mara had known and adored years longer than she’d known Liam. And certainly not Sam. Oh, Mara now recognized Sam and sometimes even seemed to enjoy his company, despite the fact that she’d never cared much for children, but she hadn’t a clue that the little boy was hers. Sometimes Liam found that unbearably painful. He longed to share Sam, his antics and his development, with Mara. With the Mara of the past. His loving, beautiful, fully functioning wife.

They spent half an hour with Mara, telling her about the day, how Sheila had taken Sam to the beach and allowed him to remove his shoes so the waves could tease him with the frigid water, how Liam had handled a difficult case in the E.R. He never talked down to her, and he always hoped that, if he spoke about a case that had a meaty psychological component, he might tap into the part of Mara’s brain that had once come alive with the challenge of helping a deeply troubled patient. Then they focused on Sam, who often grew impatient with the chatter. The little boy needed action. They played huckle-buckle-beanstalk, “hiding” the small pot of silk daisies that ordinarily rested on Mara’s night table in various places around the room. They made sure the daisies were always in plain sight, but it still took Sam minutes to find them each time, and he would let out a yelp and holler, “huh-buh-besawk!” when he did. It made them laugh, made Mara’s smile grow wider, although Liam doubted she understood the game. After the fourth time they hid the flowers, Liam noticed Mara’s eyelids growing heavy and knew she’d had enough of her visitors for today.

“Let’s go,” he said to Sam, lifting him into his arms.

Sam let out a sound of pure desolation, pointing to the daisies as Sheila placed them back on Mara’s night table. “Huh-buh-besawk,” he said, but it came out as a grief-stricken moan.

Liam grinned and kissed his temple. “Sorry, sweetheart,” he said. “We can play some more when we get home.”

“And someday, maybe Mommy will be able to play it with you, too,” Sheila said, and Liam gritted his teeth. He hated it when she talked like that. Hated her denial of Mara’s condition, although to tell the truth, he had a bit of it himself. When Sam was old enough to understand, he would have to put a stop to Sheila’s verbal wishful thinking.

He leaned over to kiss Mara on the cheek. Her eyes were now closed, and he knew she was no longer aware of his presence.

They walked through the corridor toward the foyer, stopping briefly to speak with one of the nurses about Mara’s medical treatment, and as they were walking out of the building, Joelle was walking in. Thursday night. Joelle always visited Mara on Thursday nights. He’d forgotten and hadn’t been prepared to see her, and now, his defenses down, he felt a rush of love, gratitude and the adrenaline that accompanied desire. Followed quickly by guilt, the impulse to run from her rather than to her.