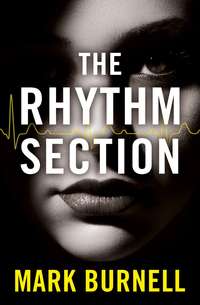

Полная версия

The Rhythm Section

Joan was peeling the wrapper off her third packet of Benson & Hedges of the day. ‘You’re shaking.’

It was true. Stephanie’s hands were trembling. ‘I’m tired, that’s all.’

For Anne’s sake, she hadn’t returned to Chalk Farm, so the next two nights had been spent upon the lumpy sofa currently occupied by Joan’s sprawling bulk. Uncomfortable nights they had been, too; once the heating cut out, it had been freezing, so she’d curled herself into a ball and pulled two coats around her to keep warm. Then she’d sucked at the gin bottle until she’d passed out, managing three hours’ sleep the first night and two the second. Now she was paying the price for it.

Shrouded in smoke, Joan was chewing peanuts while flicking through the TV channels with the remote. On the floor, next to her overflowing ashtray, there were three phones, waiting for business. None of them was ringing. She said, ‘He’s ready when you are.’

‘What’s he like?’

‘Big bloke. I think he’s had a few.’ She glanced at Stephanie through her tinted lenses and shook her head. ‘Better pull yourself together, girl. You don’t look a million dollars.’

Joan looked like a beached whale. In Lycra. Stephanie said, ‘Who among us does?’

She poured herself half a mug of gin, stole one of Joan’s cigarettes, and went to the bathroom. She washed her face, the cold water bringing temporary refreshment, before applying foundation and mascara. When she looked this bad, Stephanie always tried to draw attention to her mouth and to her eyes, which were deep brown beneath long, thick lashes. The lipstick she selected was a bloodier red than usual. No matter how emaciated the rest of her became, her fleshy lips looked as ripe as they ever had.

She changed back into her lacy black underwear and fastened her suspender-belt. There were mauve smudges on her thighs, souvenirs from anonymous fingers that had pressed into her too eagerly. The bruises around her wrists had faded to a band of pale yellow that was barely noticeable.

She drained the gin, took a final drag from the cigarette and rinsed out her mouth with Listerine. Then she took a deep breath and tried to clear her mind. But when she caught her reflection in the mirror, the feeling returned; the fear of the stranger, the fear of fear itself. It was in her stomach, which was cold and cramping, and in her throat, which was arid and tight.

To the cadaverous face in the glass, she whispered a terse instruction. ‘No. Not now.’

‘Hi, I’m Lisa. What’s your name?’

He thought about it, presumably choosing something new. ‘Grant.’

Joan was right about his size. Not only was he tall, but he was massive. An ample gut hung over the top of black trousers that looked painfully tight. Stephanie never knew that Ralph Lauren shirts came in such a gargantuan size. His sleeves were rolled up to the elbow, exposing thick forearms, each of which sported a large tattoo. His hair was buzz-cropped and a band of gold hung from his left ear. But the watch on his wrist was a Rolex. He looked as if he was in another man’s things. He looked like an impostor. Then again, they nearly always did.

‘What are you looking for?’

He shrugged. ‘Dunno.’

Stephanie put her hand on her hip, as she always did at this moment, allowing her gown to fall further open. In the right mood, it felt like a tempting tease. Today, it felt cold and sad. She watched his eyes roll down her body. ‘I start at thirty and go up to eighty. For thirty, you get a massage and hand-relief. For eighty, you get the full personal service.’

‘Sex?’

She wanted to snap but managed to restrain herself, forcing a smile instead. ‘Unless you can think of something more personal.’

Grant frowned. ‘What?’

Stephanie saw the fog of alcohol clouding his eyes. ‘So, what do you want?’

‘The full … thing … service …’

‘That’s eighty.’

‘Okay.’ When he nodded, his entire body swayed.

‘Why don’t we get the money out of the way now?’

‘Later.’

‘I think now would be better.’

‘Half now, half after?’

‘No. Everything now. It’s better this way.’

His mouth flapped open, as though he were about to protest, but no sound emerged. So he stuffed a hand into his pocket and pulled out a fistful of fives and tens. As he came close, she smelt the alcohol on his breath and the body odour that is peculiar to sweat. With fat, pink fingers, he sorted through the grubby notes and handed them to her.

She counted quickly. ‘There’s only seventy here.’

‘It’s all I got.’

‘It’s not enough. Not for sex. Perhaps there’s something else you’d like?’

He grinned stupidly. ‘Come on,’ he slurred. ‘Ten quid. That’s all it is …’

‘Yeah, I know. Ten quid too little.’

‘It’s my birthday on Saturday.’

Stephanie was aware of her irritation rising to the surface, the blood flushing her skin. ‘So come back then. And make sure you bring your wallet.’

Her change in tone seemed to have a sobering effect upon him. He straightened. ‘What do I get for seventy?’

The words seemed to echo in her skull. What do I get for seventy? The question was not new, nor was the contempt in the voice. Yet Stephanie had suspected there might come a moment like this. For several days, she had known something was wrong, but she had refused to accept it. Initially, she’d tried to ignore it, to convince herself she was imagining it. Later, as she felt the cancer of anxiety spreading within her, she had tried to crush it with reason. And when that had failed, she’d tried to blot it out chemically.

It had nothing to do with Grant. It could have been anyone. What do I get for seventy?

‘You don’t.’

Grant looked perplexed. ‘What?’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘You said you went from thirty up to eighty. Now what do I get for seventy?’

‘You don’t understand. I’m not doing anything. Not for seventy, not for eighty, not for one hundred and eighty.’ She thrust his money back at him. ‘Here. Take it.’

He swiped her hand away, the notes fluttering to the floor. ‘I don’t want it. I want –’

‘I know what you want. But you can’t have it.’

He took one step towards her and it was enough. Her right hand had already reached behind her and found what she knew would be there; on the table, by the bowl – an old champagne bottle, half a candle protruding from the top, its neck coated in dribbles of cold wax.

She swung her arm with all the might she could muster, creating a perfect arc. The glass exploded against the side of his face. Splinters showered on to the naked floorboards. Stephanie watched the lights go out in Grant’s eyes. He managed to raise a hand to his lacerated cheek but he was not aware of it. He lurched one way and then the other, before collapsing. The floor shook beneath the impact of his body.

It took Joan ten seconds to waddle through the door. She looked at the body on the floor and then at Stephanie, who was crouched over him, still clutching a fragment of the bottle’s neck in a way that suggested she might yet drive it into him.

Joan put a hand to her mouth. Stephanie turned to look at her, not a trace of an emotion on her face. Through her fingers, Joan muttered, ‘Oh shit, what’ve you done?’

Stephanie walked past her without a word and headed for the room next door. She shrugged off her gown and picked up her coat. Joan followed her into the room. ‘What’re we gonna do with him?’

Stephanie looked for the small rucksack that contained her worldly belongings. She opened it, checked nothing was missing and then fastened the straps. Then she started to put on her coat.

‘West’s gonna go fucking mental,’ Joan said. ‘We’ve got to get this wanker out of here.’

Stephanie looked at her. ‘If I were you, I’d get out of here. Right now. That’s what I’m going to do.’

‘You can’t just walk out. He’s downstairs, for God’s sake. For all we know, he could’ve heard it. He could be on his way up here right now.’

‘Exactly. And when he finds out about this, how do you think he’s going to react? Do you think he’s going to look for an explanation? Or do you think he’s going to look for someone to take it out on?’

Joan’s expression darkened. ‘Well, it won’t be me, love. I ain’t the one that done it.’

‘Fine. That’s your decision. But it’s not mine.’

‘I ain’t going. And you ain’t, neither.’

Joan reached for the phone. Stephanie grabbed her bag and ran.

Whoever answered the phone on the third floor took their time. The door was still shut when Stephanie passed it. The heels on her shoes slowed her on the uneven stairs but she reached the ground floor and was halfway to the front door when she heard the shout from above, followed by the multiple thump of descending boots.

She knew she had to lose them immediately. If her pursuers saw her, they’d catch her. She turned right and then right again, out of Brewer Street and into Wardour Street, before taking the first left into Old Compton Street and another first left into Dean Street. She never dared look back.

It wasn’t yet ten in the evening. The area was busy, which was a blessing. She turned right at Carlisle Street and only stopped running when that led into Soho Square.

The distance covered wasn’t great but her lungs were pleading for mercy. She slowed to an unsteady walk. It was then that she noticed that her coat was still only half-buttoned, which explained some of the astonished looks she’d seen on the faces that had blurred past her. Black underwear and a suspender-belt were all she had on beneath the coat. And given her appearance, she suddenly realized that if her hunters were asking pedestrians for the direction she’d taken, she’d be the freshest thing in the memory of just about everyone she’d passed.

She fastened the remaining buttons to the throat and forced herself into another run. She’d known she was unfit, but she’d never guessed that her physical decline had become so acute. For the moment, fear compensated but she knew it wouldn’t last.

She took Soho Street out of the Square and then crossed Oxford Street before turning round for the first time. There were no obvious signs that she was being followed. She headed up Rathbone Place and turned right into Percy Street. Her mind was starting to function again. The immediate danger appeared to have been averted but there was a more sinister threat ahead. If her pursuers returned to Brewer Street empty-handed, West would use his network to try to locate her. The word would go out and the search would be on. When that happened, anybody she passed on the street would be a potential danger.

She wondered how long she had and where she should go. Chalk Farm was out of the question. In fact, anyone she knew was out of the question; it was too risky to involve them. Which was why she chose Proctor. She felt nothing for him.

At the junction with the Tottenham Court Road, she turned left and headed north. She found a working BT phone-box outside the National Bank of Greece. She dialled and luck was with her.

‘It’s Stephanie Patrick.’

If surprise had a sound, it was to be found in Proctor’s silence.

She said, ‘Can we meet?’

He was trying to gather himself. ‘I guess … sure. Sure. When?’

‘Now.’

‘Now? Er, that’s not very convenient. I’m busy. Working –’

‘I’m in trouble. I need help. And I need it right now.’

4

I am drinking a cup of coffee in the McDonald’s on the corner of Warren Street and the Tottenham Court Road. I keep my head bowed, aware of the strange looks that I am attracting from some of the other patrons. I should be standing in the entrance to the Underground station across the street, but it’s cold outside. I’ll return there when it’s time to be collected.

I am trying not to think about the man I hit or the situation in which I find myself. Instead, I am thinking about the trigger.

I am wondering what it is like to be in a plane crash. To be going down and to be conscious of it. To know that you are doomed. What does that feel like? What does it sound like? These are matters that I’ve considered on too many occasions to count. The images creep up on me in the night. I see Sarah, my sister, her hair on fire. David, my younger brother, looks at the stump on his shoulder from where his arm used to hang. And my parents are ash, instantly incinerated and scattered on the wind.

These are the things that wake me at night. They’re the reason I drink myself to sleep. That’s where they belong – in the sleeping world. But tonight, they crossed over.

I looked at Grant – whoever he really was – and I thought about what we were going to do. For seventy pounds – not even eighty – since I would have discounted myself in the end. Except, it never came to that. Instead, I imagined my parents were in the room too, with David on one side, Sarah on the other, the smell of charred flesh everywhere, the floor slippery with their blood. I saw myself on all fours, Grant drunkenly ploughing into me from behind, my family watching, their total disappointment evident through their hideous wounds.

It has never happened before. I have never seen them when I’ve been selling myself. Some instinct has always blocked them – and anything I have ever cared about – from my mind. But lately, there has been something wrong. I’ve felt it building within me, a pressure in search of release. And now I know the cause.

Proctor. Proctor and his far-fetched conspiracy theories. He has resurrected the ghosts. He is to blame.

Outside, on the Euston Road, running over the underpass, there is a construction of concrete with a metal grille set into it. Perhaps it is some kind of ventilation unit. I don’t know. Anyway, beneath the grille, there is some graffiti which I noticed before coming in here.

It says: NO ONE IS INNOCENT.

Proctor was driving a small, rusting Fiat. Stephanie had imagined he’d be in the latest BMW or Audi, something sleek and German. He leaned over and opened the passenger door. Stephanie stepped out of the entrance to Warren Street Underground station and crossed the pavement.

‘You’re twenty minutes late.’

‘The car wouldn’t start.’

She looked at it disdainfully. ‘You don’t say.’

Proctor’s surprise was self-evident. ‘For someone in trouble, you’ve got a crappy way of saying thank you.’ When she failed to speak, he said, ‘Are you getting in the car, or not?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘You don’t know? I thought you needed a place to stay.’

‘I need a safe place to stay.’

The wind blew newspaper along the pavement. She shivered.

Proctor nodded slowly. ‘I won’t harm you –’ She looked unconvinced. ‘– I promise I won’t.’

‘You can’t have sex with me.’

He found her frankness disarming. ‘What?’

‘You can’t have sex with me.’

Proctor attempted a little levity. ‘That’s a relief. You’re not my type. Now get in.’

But Stephanie looked as serious as before. ‘I mean it.’

‘I don’t believe this. Look, you asked me. Remember? I was the one who was working at home, who pulled on his shoes and drove up here to collect you.’

She clutched her coat at the throat. ‘I won’t let you –’

‘I don’t want to have sex with you. You look like death warmed up. Now are you getting in the bloody car or not? Because I’m not hanging around here all night waiting for the police to arrest me for kerb-crawling.’

Once again, Proctor saw a look that could have been sorrow, hatred or fear. Or all three. After a final suspicious pause, Stephanie got into the car.

Proctor kept both hands on the wheel and looked straight ahead. ‘I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have said that.’

‘Forget about it. You’ve no idea how refreshing the truth can be.’

It takes me time to remember where I am. This sofa is not in Brewer Street. It is in Bell Street, which is between the Edgware Road and Lisson Grove. I am in the living room of Proctor’s flat.

My life is precarious enough without climbing into strangers’ cars. Last night, I needed to get off the street, and to rest, so I was grateful for his intervention. But now that it is morning, I’ve got to think ahead and make plans. I have to keep moving – moving prey is harder to catch – until I can find somewhere secure to lie low. And for that, I’ll need money. The three hundred and fifty-five pounds that I lifted from the businessmen in King’s Cross will fuel me for a while but it does not represent a passport to a new life.

As I rise from the sofa, I become aware of how ill I feel. This doesn’t seem like a regular hangover; I ache all over and I feel sick. I am simultaneously hot and cold. Maybe this is my body protesting yet again at the way I have treated it.

I assume that Proctor is still asleep. I move quietly. When we returned here last night, we didn’t talk much. He showed me where the bathroom was and I changed into the jeans and sweatshirt that I was carrying in my rucksack. Then he sat me on this sofa and poured me one whisky after another. I don’t remember how many it took to eradicate my in-built sense of caution. Exhaustion was to blame, but by the time I was ready to talk, I was ready to sleep. Proctor realized this and fetched me a pillow and some blankets. I suppose he thought we’d talk this morning. He’s going to be disappointed.

He was wearing a worn leather jacket when he picked me up. I cannot see it in this room so I put on my shoes, gather my things, fasten the rucksack and pull on my overcoat. Then I open the door as quietly as I can and I tiptoe past Proctor’s bedroom, which is on the left, and make my way down the hall.

My temples throb. I feel nauseous.

Before I reach the front door, there is a final room on the left. Somebody could have used it as a second bedroom. Proctor uses it as an office. There are two tables in it; on one, there are box-files and correspondence, on the other, a computer. On the back of the chair between the two hangs his leather jacket. I creep into the office and run my hands through the pockets until I find his wallet. I open it up and ignore the cards. I am only interested in cash. He has eighty pounds; three twenties, two tens. I fold them in half.

Which is when I hear him behind me.

‘Are you looking for something of yours?’

Stephanie spun round. Proctor was filling the doorway, blocking her exit.

‘Or just something of mine?’

The wallet was in her hand.

Proctor was wearing track-suit bottoms and the same black shirt he had worn the night before. There had not been time to fasten the buttons. On one side of his head the hair was flat to the skull, on the other it stood out like bristles on a brush.

He looked dejected, not angry. But Stephanie had long since learned to distrust appearances. He said, ‘All you had to do was ask. I would have given you money.’

‘Yeah, right …’

‘It’s true.’

She squinted at him. ‘And why would you do that?’

‘Because I know about you.’

His hand was outstretched, waiting for the return of his wallet. Stephanie stepped forward to give it to him. And then she charged, ramming his chest with her shoulder, knocking him off-balance. Clutching the wallet as tightly as she could, she sped across the hall and reached for the front door. But Proctor’s hand grabbed her shoulder, spinning her round. In an instinctive continuation of the movement, she raised a fist and punched him on the jaw. Proctor recoiled, amazed by her speed and strength.

She tugged at the front door catch repeatedly but couldn’t open it. The knowledge came to her gradually, sapping her strength. She let go of the catch, her hand falling limply to her side. When she looked round, she saw the keys dangling from the key-ring that was hanging on the tip of his forefinger.

His other hand was massaging his jaw. ‘Double-locked, just in case,’ he said.

The front door was at the end of the corridor. Proctor had her penned in; there were no rooms to run to, no surprises left to spring. Stephanie’s reactions were automatic, a by-product of experience. She retreated into the corner and slid to the floor. Mentally, she began to go blank, closing everything down, numbing herself. When Proctor took a step towards her, she wrapped her arms around her head and pulled herself into the smallest human ball possible.

‘What are you doing?’

She braced herself for the first blow.

‘I’m not going to hit you, Stephanie. I don’t want to hurt you.’

Those very words had been the preface to a savage beating more than once. She knew that Dean West always tried a little kindness before administering his punishments. She stayed still, knowing better than to lift her head.

‘I’ll tell you what, I’m going to move back. All right? I’m going to move back to my office doorway and then I’m going to sit down on the floor, like you. And when I have, you can look up. Then we can talk. Is that okay?’

There was no reply.

‘That’s all I want to do. Just talk.’

She sensed his retreat before allowing herself to peep through crossed arms.

‘See? I can’t hurt you from here.’

Stephanie felt dizzy. She swallowed.

‘Where were you going to go?’

No answer.

‘Is there anywhere? Anyone?’

She was trembling.

‘What about last night?’ he asked. ‘Do you want to tell me what that was all about?’

She kept her head protected.

‘Look, I know you don’t trust me – there’s no reason you should – but I really have no interest in you, apart from what you can tell me. I have things to tell you too but if you don’t want to hear them –’

‘I don’t want to hear anything,’ she whispered.

Proctor shook his head. ‘This is your family we’re talking about.’

Stephanie shrugged.

‘How about if I asked you some general questions? Would you answer them?’

‘No.’

‘Why not?’

‘There’s nothing you need to know about me or about my family.’

‘I see. Well maybe you could just sit and listen. I’ll tell you what I’m working on, what I’ve found out, how I’m –’

‘Don’t you get it yet? I don’t care.’

‘No. I don’t get it. I don’t get it at all. If it was my family on that 747, I’d want to know why it went down and who was responsible. I’d want justice. For them and for everyone else on board. And for all their relatives and friends who’ve had to deal with the aftermath. That’s what this is about, you know. That’s what this investigation was when I started. A human interest story. What happens to the families and friends of the dead a couple of years down the line when it’s no longer news? How do they cope in the long term? You may not talk to me but there are others who have. I’ve seen their grief. I’ve felt it. Two years plus hasn’t diminished it. They’ve learned to live with it – some of them, anyway – but the wounds haven’t healed. And they probably never will. Every single one of them has suffered and –’

‘Do you think that I haven’t?’ she snapped. ‘That I still don’t?’

‘Of course not. It’s just that –’

‘Just what? Odd that I don’t like to talk about it to journalists? I bet you think my situation is a consequence of the crash, don’t you? That would be a good story for you if it was true, wouldn’t it?’

He wanted to say yes, but said, ‘I don’t know enough about you yet. I can’t tell.’

‘You see? You’re lying like everyone else. I can see your outline from here: a family in ruins, four dead, two survivors, one who copes and one who can’t. Like you said, a human interest story.’

‘My story is changing.’

‘What makes you think I want to see my life in print?’

‘You wouldn’t necessarily feature.’

‘Not unless I improved the story. Then you’d include me. Right?’