Полная версия

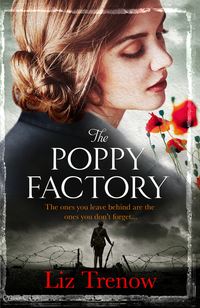

The Poppy Factory

‘Jess. Thank Christ, it’s you,’ he whimpered, through gritted teeth. ‘Just save me feckin’ life, will ya? Get me home for Chrissake. Please.’

‘Don’t you worry, you’re going to make it,’ she said, trying to convince herself as much as him.

Vorny slithered down the slope to join her and they worked together, wrapping the shattered stumps with white dressings, all the while talking to the lad, trying to calm him.

‘Nearly there. MERT’s on its way. We’re going to get you out of here. Hang in there. You’re going to make it.’

Vorny set up a drip into one arm and held the bag high, squeezing it to push the life-saving liquid into Scott’s system, while Jess pulled out a morphine autojet and punched a hefty dose directly into the muscle of the upper arm on the other side. ‘That’s it, Scotty. When you wake up you’ll be in Bastion,’ she said, as the howls tailed off into moans.

By now Captain Jones was on his feet but very pale and holding his hand gingerly, with the other lad, McVeigh, who was shocked and deafened, but otherwise unharmed. They’d identified a landing site just beyond the brown poppy field at the edge of the village. The helicopter was circling, just about to land, and she was heading across the field behind the stretcher team, carrying Scotty’s pack, when the shooting started. There was no cover, and it seemed to be coming from both sides.

She dropped to the ground, cursing the fact that any delay could cost Scotty’s life after all the work they’d done to save him. But as the helicopter turned away without landing, and the firing continued without any apparent response from their own side, she realised it was not only Scott’s life in danger. Bullets could slice through the brittle brown stems of the crop at any moment. The adrenaline rush that had kept her going throughout the time they’d been working on Scotty was dissipating, and she began to panic. It was then that she saw the red poppy.

‘Christ, Jess, what the fuck are you playing at?’

Dave’s shout, close to her ear, brought her instantly back to the High Street in the pouring rain, a scene painted in grey and red, the smell of blood, the young man’s groans, his shattered limb in her arms. She had absolutely no idea how long she’d been kneeling there.

‘Let me take over,’ Dave barked, taking hold of the leg and shoving her aside brusquely. ‘Just give the poor sod some morphine. Get a drip going and pump in some fluids, for Christ’s sake.’

Dragging herself back to the present, she stood and picked up her pack. Through the shattered glass of the shop window she could see an array of meat, liver, sausages, lamb chops, trussed chickens, all glistening with broken glass. The centrepiece was a large whole leg of lamb, the severed end pointing towards her, a neatly trimmed version of this young man’s leg. Like Scotty’s legs after that blast.

She forced her eyes away, searching the pack for a morphine syringe.

‘I’m just going to give you something for the pain,’ she said, squatting down by his head. But when she looked into his face she could see that he had gone, his eyes rolled back, his skin a deadly grey.

She shook his shoulder. ‘Stay with us,’ she shouted, shaking him harder. She pressed her finger to his neck.

‘No pulse, Dave. Christ, he’s got no pulse.’ She ripped open his jacket and shirt, and pressed the pads onto his chest. ‘Flatline.’

‘I’ll secure his airway,’ Dave shouted. ‘Start CPR, now.’

No, no, no, no, she muttered to herself, in rhythm with the pumps on his chest, like a mantra. Not again, not again. It can’t be, can’t be. Now, the rest of the world disappeared and the only thing that mattered was counting out loud the chest compression pumps: one – two – three – four – five – six – seven – eight – nine. Eighty to a hundred pumps a minute for two minutes, a quick check of the pulse and then start again. Dave was squeezing air into his lungs from the bag now, twelve breaths a minute. If we keep doing this he will come back, she said to herself, I’ve seen it happen, just so long as we can keep it up.

Just as the muscles in her arms felt as though they would crumple with exhaustion Emma returned and took over for a while, and they alternated for what seemed like hours, all through loading him onto the ambulance and the crazy race back to the hospital; even as they were wheeling him into A&E.

The doctors declared both casualties dead on arrival. They were the young parents of the baby. The old man who’d lost control of his car and driven onto the pavement at forty miles an hour was completely unharmed.

When they got back to the ambulance station Dave said, ‘Want a coffee?’

She nodded numbly and followed him into the kitchen, barely aware of her surroundings, finding it strange that she could even breathe or put one foot in front of another when she felt so completely shell-shocked. He placed a mug of hot sweet tea onto the table in front of her but when she went to pick it up her hands shook so badly that she slopped it all over her uniform.

He put a gentle hand on her shoulder. ‘It happens to all of us, you know,’ he said, kindly.

She shook her head vehemently. ‘No, it doesn’t happen to all of us, not like that. You saw me, Dave. I lost it again. Some kind of flashback thing. God knows how long it was before you arrived and took over.’

‘Only a few moments, I’m sure. Besides, you’d already controlled his bleeding.’

‘But the delay could have meant the difference …’ The thought was simply too enormous and too terrible to contemplate. She felt overwhelmed and exhausted; barely able to think straight.

After a long pause Dave said: ‘I think you need to take a few days off. Why don’t you ask Frank?’

‘Oh God, I couldn’t face Frank, right now.’

‘Do you want me to ask him for you?’

She nodded.

‘Okay. I think you need to talk to someone, but perhaps not today. The best thing for you now is to go straight home, have something to eat and a couple of glasses of wine. Try to think about something else. I’ll text to let you know what Frank says.’

It was this simple act of kindness and understanding which finally broke the dam, opening the door to all the horror, the guilt and the shame. She began to weep, with long, agonising gasps that seemed to wrench all the air out of her lungs. Dave moved his arm around her and she rested her head on his warm, broad shoulder till the sobs abated.

Chapter Four

She was relieved to see her father in the station car park because he wouldn’t ask too many questions; after a heavy date with a whisky bottle, she was feeling particularly fragile.

When she’d got back to the flat the previous day she’d found it deserted and remembered that Vorny and Hatts were away on exercise for two weeks. She slumped down on the sofa and wept, desolate and desperate for someone to talk to. Why weren’t they here, when she’d needed them most? She considered calling Nate but decided she couldn’t dump her problems on him, not just yet. After a while she dried her eyes and stomped around the flat wondering what to do with herself. Then, reluctantly, she dialled her parents’ number.

‘I’ve got a few days unexpected leave, Mum. Can I come and stay?’

‘Of course, dear. Are you all right?’

‘Ish. Talk tomorrow, okay? I’ll be there on the five o’clock train. Can someone pick me up?’

As they drew up to the house her mother was on the doorstep, with Milly the dog, both regarding her with inquiring eyes. Why the unexpected leave? Why wasn’t she spending it with Nathan? Of course her mother was far too wise to ask directly. Jess would share any problems, in her own time. She always did.

‘How’s things?’

‘Fine, thanks. Glad to be here.’

‘You look pale, love. Are you feeling okay?’

‘Just a bit weary. Heavy week.’

The truth was that she didn’t really feel anything much right now, except numb and confused. All her adult life had been spent working towards, training and then becoming a medic. She’d wanted to make a difference, to save lives and she’d loved it, mostly. Until yesterday she had been determined to spend the rest of her life doing it, couldn’t imagine any other form of career.

But somehow all that certainty had now disappeared, washed away like the poor young man’s blood on that dismal pavement. She had broken her promise to James, her vow to prevent anyone dying through any delay in stemming their loss of blood.

The future felt like a quicksand, untrustworthy and perilous. Last night, during her long commune with the bottle, she’d argued with herself, sometimes out loud, as the logical, calm voice of reason struggled to be heard over what her instincts seemed to be shouting:

You’re a good medic, well-trained, highly experienced. You’ve made a difference, even saved lives.

I’ve failed to save lives. I failed that young man. I punched that idiot in the street.

Just a couple of blips, you’ll get over it.

It’s not that. I can’t trust myself any more: the flashbacks, the anger. I failed my promise to James.

Just two events in four months, Jess.

I’m a danger to patients. My confidence is gone. The thought of going back to work makes me feel panicky and sick.

You could get help, counselling perhaps? That’ll sort it.

Do I want to put myself through all that self-examination crap? Anyway, I don’t know if I really want to go on putting myself on the line every day.

Okay, so give up being a medic. But you need to earn a living somehow. What would you do instead?

Oh Christ, that’s it. What else could I do? There is nothing else.

The argument raged in her head until, finally, she’d passed out, fully dressed, on the sofa.

Jess had envisaged walking with her mother on the beach, perhaps sitting on the dunes, a neutral, impersonal place to talk because you naturally sat looking outwards, your eyes drawn to the sea and the horizon, rather than facing your companion. Quite why this made it so much easier to be honest with yourself she never completely understood, but it always seemed to work.

She recalled days and nights of teenage angst when she would rush to the sea, weeping her eyes out over some spotty, undeserving youth, or spending hours with her best friend in the dunes dissecting every nuance of their latest romances, imagined or real. Alone or in company, self-pity never survived for long out on the beach. The soothing, rhythmical shush of the waves, the wide open skies and grey sea stretching to infinity always helped her to find a sense of proportion, reminding her of how small and insignificant we are in this vast universe, how unimportant our problems in the wider scheme of things.

But this time it didn’t turn out like that.

After breakfast, she’d just made another pot of coffee and was sitting at the kitchen table while her mother fussed around, washing up, putting away. Her father had drifted off to his greenhouse.

‘Look what I got for supper,’ Susan said, pulling something out of the fridge. ‘I went to that lovely butcher’s yesterday. I know it’s your favourite.’ She placed the parcel on the table and unwrapped it, revealing a large leg of lamb, its severed flesh oozing dark red blood onto the worktop.

Jess had time to blurt out, ‘Lovely …’ before the nausea hit her, like an unstoppable wave. She made it to the cloakroom just before she vomited, violently and uncontrollably, into the toilet, groaning with pain as her guts turned themselves inside out. She gagged, again and again, her throat burning with the vicious acid residue of last night’s whisky.

She heard her mother at the door and then by her side, and a soothing hand stroking her shuddering back. When it was all over she allowed herself to be led back to the living room, on trembling legs, gratefully accepting the glass of cool, clear water she was offered.

Her mother sat down on the chair opposite. ‘Are you feeling better now?’

Jess nodded.

‘What was it? Something you ate, do you think?’

Jess took a sip of water, trying to delay answering until she’d put her jumbled emotions into some expressible order. She was about to brush it off with a jokey remark about a dodgy take-away but then, as if the phrase had formed itself independently of any conscious thought, the words came out of her mouth: ‘I’m giving it up, Mum.’

‘Giving what up, love?’

‘Being a paramedic. I’m going to quit. I can’t do it any more.’ Just as soon as she heard herself admit it, an almost overwhelming wave of relief sluiced through her body.

Her mother’s eyes widened, but she managed to keep her voice calm. ‘This is sudden, Jess. I thought you loved the job? Has something bad happened?’

The tears began to flow freely as she found herself describing the events of yesterday. The way she’d lost control, found her mind flashing back to the desert, the shocking outcome.

The discussion that followed went much along the same lines as the internal debate she’d had on the sofa with the whisky bottle last night. Her mother made all the reasonable responses: take your time, seek some help, you’re a great medic, it would be a loss to the service, it’s what you’ve been working for all your life. But the more the conversation continued, the more Jess became convinced that what her inner voice had been telling her head was right. She couldn’t carry the responsibility of saving people’s lives, not any longer.

Eventually her mother stopped offering suggestions. ‘It’s your life, my love. Whatever you decide will be for the best.’ She leaned over and stroked Jess’s hand. ‘But shouldn’t you also get yourself checked over by a doctor to find out what caused you to be so violently sick?’

Jess hesitated, unwilling to inflict another disappointment, but she would have to admit it in the end. ‘I’m sorry, Mum, but it was the leg of lamb. It brought everything back. It’s what that terrible stump yesterday reminded me of, and when I stood up afterwards there was a butcher’s just beside us and the meat was just like that poor young man’s flesh.’ She shuddered involuntarily, remembering the red of the meat and the silvery slivers of shattered glass.

They had fish and chips for supper instead and, much later that evening, after her father had gone to bed, they sat on the patio together watching the stars come out. It was September now, the evenings were drawing in and there was a dampness in the air with that autumnal countryside smell. She always found this time of year melancholy: the swallows gathering for their long migrations, the changing sounds of birdsong, dew on the grass in the morning, the yellowing of the leaves. They all felt like endings. Only this year she was facing a very personal ending, a big, terrifyingly full stop to what had been driving her, her reason for living, her passion for the past ten years.

After a while it grew cold and they went inside. ‘Whatever am I going to do with myself now, Mum?’ Jess said, cuddling up on the sofa with Milly, who wasn’t usually allowed to sit there.

‘Have you got any ideas?’

‘Not a clue,’ she admitted.

‘What about something to do with animals?’ Susan said. ‘You’ve always loved them, and when you were a very little girl – before you joined the St John Ambulance – you used to say you wanted to be a vet.’

‘It’s a six year training. Anyway you have to be super-bright. I’d never have got in with my two Bs and a C.’

They chatted for a while and then, out of the blue, her mother said, ‘You know what you told me about the leg of lamb today?’

‘Uh huh.’

‘It reminded me of something I’d read somewhere and it was really annoying me because I couldn’t remember where.’

‘And have you remembered now?’

‘I have. Something rather like that happened to your great-grandfather Alfred, too.’

‘Like what?’

‘He was in the First World War and came back injured – lost a leg. Afterwards he tried working as a butcher, but he couldn’t take it because the raw flesh reminded him of something he’d experienced in the war.’

‘That’s strange. How do you know all this, anyway?’

Her mother disappeared upstairs and returned a few minutes later with a small cardboard box. ‘It’s all in here,’ she said. ‘Your great-grandmother’s diaries.’

As Jess opened the box, a comforting, musty smell of old paper wafted out into the room. Inside were stacked six dog-eared notebooks, the old-fashioned kind once issued by schools, yellowing pages of cheap lined paper stapled between soft buff-coloured covers. On the front of each one was written, in a neat rounded hand in fading blue ink, ‘Rose Barker. PRIVATE’.

‘Oh my goodness, look at this. They were written by your grandmother? My great-grandmother?’

Susan nodded. ‘Everyone knew her as Rose but her full name was Jessica Rose. You are named after her. She died when I was only five so I barely knew her, but she was a tough cookie by all accounts.’

‘This is amazing. Why haven’t I seen these before?’

‘We only discovered them after granny died last year.’ Jess had been given leave to return home for the funeral but had to fly back immediately afterwards. She’d been sad not to be able to stay longer, to help her mother with the gloomy task of sorting out her grandmother’s belongings.

‘Have you read them yet?’ Jess said, starting to rifle through the notebooks.

‘Not completely. I got up to the bit about poor old Alfie but then I got too busy to carry on.’

‘Did you know about them before?’

‘Mum never mentioned them, but then her memory was pretty dodgy and I suspect she just forgot they were there, locked way in the attic all those years.’

‘Shall we look at them together, now?’ Jess asked

Susan looked at her watch and yawned. ‘Not tonight, love, it’s gone midnight,’ she said, stroking Jess’s hair. ‘Are you coming up?’

‘In a while,’ Jess said. ‘I’m not sleepy yet. I’m going to have a bit of a read, if you don’t mind. I’m really curious to find out about Alfie.’

‘Are you feeling better?’

Jess nodded. ‘Thanks for being so understanding, Mum.’

‘No drinking now?’ She gave her daughter a stern look.

‘I’ll do my best,’ Jess said. ‘See you in the morning.’

After her mother had gone, Jess made herself a cup of coffee with a whisky chaser, and placed the cardboard box beside her on the sofa. Milly came to join her, snuggling her furry face onto Jess’s knee.

She lifted out the top notebook and flicked through the pages filled with the same careful handwriting, interspersed with stuck-in cuttings and letters. Then she checked the dates on the other notebooks to make sure they were in the right order, and began to read.

BOOK ONE

Rose Barker – PRIVATE

Monday 11 November 1918.

RED LETTER DAY!

Even now I have to pinch myself!

I have sorely neglected my writing since starting at the munitions factory, having felt so exhausted and dispirited each evening, and my entries so dull. I found these notebooks on a charity stall a few weeks ago and they are begging to be filled. And now there is so much to tell I barely know where to begin.

Today started out as another gloomy winter Monday with us all bent over our benches carefully filling shells with ‘devil’s porridge’ and then, at 11 o’clock this morning, the siren wailed. We jumped out of our skins, of course, we always do. Explosion warning? An air raid? Everyone stood stock still, looking at each other over our respirators like yellow-faced frogs. And then we twigged. We’d heard rumours and read plenty of reports in the newspapers, but no-one really believed them. There’ve been so many false promises. Could it really happen this time?

Then the boss came over the tannoy and told us it was official: fighting had been suspended on the Western Front. A moment later all the church bells of East London started clanging with a deafening din – such a surprising sound that we hadn’t heard for four years – and we were cheering and laughing so loud that we couldn’t hear the rest of what he said. But the word got round soon enough: not that we’d have gone on working, in any case, but they were closing the factory for the day.

We threw off our overalls, grabbed our coats and tumbled out into the street like a pack of puppies, where there was already such a great crush of excited people singing and cheering, running and dancing, hugging and kissing, that we could barely make our way through the streets. Being so short, Freda was virtually carried along, and I had to hold her tight so as we wouldn’t get separated. A group of young lads adopted us: ‘Come on canaries,’ they yelled, ‘we’ll look after you, show you a good time.’

On a normal day we wouldn’t have given them a second glance, but the world had suddenly been painted in bright colours and even spotty boys looked handsome. It may have been grey and a bit drizzly, but it felt as though the sun had come out, beaming down on us lot all lit up with happiness.

We had a notion to get ourselves to the West End and somewhere near Buckingham Palace cos word was that the King and Queen were going to come out and wave to us but there wasn’t a cat’s chance of that. The buses were crammed to the nines with people piled high on the top decks and hanging off the rear doorways, but they weren’t going anywhere due to the crowds. It was almost impossible to push your way through even on foot, so we just let ourselves be carried wherever the crowd took us.

We passed by Smithfield where a surge of greasy, blood-stained lads had poured out of the meat market, and on to the edges of the City where a great black wave of clerks and business types had pushed out onto the street. They were throwing their bowlers in the air, hanging out of windows and balconies and climbing lampposts, without a thought for their smart city clothes. No-one cared a jot.

The pubs were opening by now, and tankards being handed out around the crowd, and buntings being hung from upstairs windows so the city looked like a fairground. At one junction they’d set a wind-up gramophone going in an open window, and we started dancing to it. After a while, as we moved slowly forwards, the bands came out: the Sally Army, musicians from the clubs and just about anyone who had an instrument seemed to gather on every street corner and they played together, all the old favourites: Pack up Your Troubles and It’s a Long Way to Tipperary. If they stopped, someone would hand them each a pint and we’d shout for more till they tuned up again.

Freda and me both got horribly drunk and kissed a dozen unsuitable types, which as a married woman I really shouldn’t have, but we were so happy we just didn’t care.

Then there was a great roar from the crowd and people shouted ‘God Save The King’ again and again, and the musicians struck up with the national anthem. We were still in Cheapside and nowhere near The Mall, but word had spread through the crowd that King George and Queen Mary had come out onto the balcony of Buckingham Palace and waved to all those lucky beggars who managed to get within sight of them.

After He’s a Jolly Good Fellow, the crowd started on other songs and I was joining in happily until they struck up with the hymn All People That on Earth Do Dwell, and a sudden wave of sadness hit me. I don’t suppose the beer we’d drunk on empty stomachs helped, but my legs went wobbly and I felt as though I might fall over if I didn’t find somewhere to sit. I pushed my way through the crowd to the side of the road and found an empty doorstep.

Then the tears came, coursing down my face like a waterfall, as I remembered all those poor boys. Those thousands and thousands of boys, even millions, who were never coming back, who would never be able to celebrate the victory they lost their lives for. Not just Ray and Johnnie, but my uncles Fred and Ken and the three Garner brothers, Billy and Stan, Tony and Ernest, Joe, William and Tom Parsons. And those were just the ones in our neighbourhood we knew well.