Полная версия

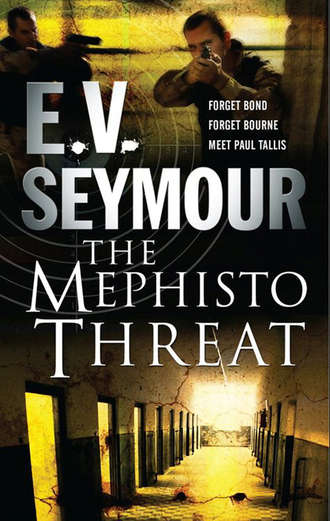

The Mephisto Threat

‘What you need is an Apple Mac, a proper computer, not some crappy old PC,’ he told Tallis.

Whenever people offered that type of advice, Tallis knew it meant only one thing: forking out. ‘It’ll cost a bit,’ Jimmy said, shrewdly reading his expression, ‘but worth it. And you get ever such good back-up if things go wrong.’

‘You on commission, or what?’ Tallis grinned.

‘Nah, just got taste.’ To prove the point, Jimmy invited him round to examine his own machine.

‘Your mum in?’ Tallis said warily. Jimmy’s mum had a bit of thing for him. Well, a bit of thing for any man with a pulse, if he was honest.

‘Nah, gone to the social club.’

Twenty minutes on, Tallis was sold. Two days later, he was the proud owner of a flat-screen seventeen-inch iMac with web cam and full Internet connection.

The bungalow looked the same: elderly. In the carport, his Rover stood mute and accusing. He presumed nobody thought it worth nicking.

Inside there was a musty and neglected smell. After dumping his stuff in the bedroom, he set about opening all the windows and, ignoring the phone winking with messages, stepped out into the garden. Since losing interest in home DIY, he spent more time outdoors. Not that his efforts proved much of an improvement. The grass had grown with a speed that was only rivalled by weeds, his half-hearted attempts to nurture some plants whose names escaped him a resounding failure. Still, there were always the birds. He had a bit of a theory about them. In the criminal sphere, he reckoned the sparrows and robins were bobbies on the beat, wagtails private investigators, rooks and crows hit men, buzzards and sparrow hawks the Mr Bigs. The blackbirds, clever little bastards, were CID on account of setting up their own early warning cat alarm. Every time next door’s moggy appeared in his garden, there would be the most terrific racket, giving him enough time to turn the hose on the feline intruder. He thought the bloody thing would have got the message by now, but it kept coming back, strutting its stuff as only cats could. Maybe they were the real Mr Bigs, he thought idly, his thoughts turning to Garry Morello once more, and the potential people he’d crossed.

Back inside, Tallis made himself a cup of coffee, black, with sugar to make up for not having any milk. Finding a pen and a piece of paper, he steeled himself to play back his messages. Only one message was urgent. It was from his mother. His father had died.

‘Where have you been? We’ve been trying to get hold of you.’ It was Hannah, his sister.

‘I’ve been away.’

‘Well, we know that,’ she said accusingly. ‘Why didn’t you tell anyone?’

‘It was a spur-of-the-moment thing. Look, when did he pass away?’

‘Over a week ago.’

Tallis closed his eyes. Perhaps they’d already buried him. Please.

‘We’ve been waiting for you to get back so we can have the funeral.’

Oh, God. He muttered apologies, his sister admonitions. ‘How’s Mum?’ he said.

At the mention of their mother, some of the heat went out of Hannah’s voice. ‘A little better than she was. Hard to say.’ She paused. ‘Look, I know you and Dad never got on, but now he’s dead, you might feel…’

Nothing, he thought coldly. ‘Hannah, let’s concentrate on Mum, make sure she’s looked after.’

‘Of course, but—’

‘Mum must come first,’ he said firmly. This was not the time for an examination of his feelings towards the man who’d done his best to break him. And yet the man had been his father and, as his son, Tallis felt it wrong to harbour such animosity towards him. He’d often wondered what it would feel like when his dad died. If he was honest, there had been times in his life when he’d wished for it. Now that his father was dead, his emotions were less easy to pin down.

The silence throbbed with hurt and disappointment. Then he heard his mother saying something in the background.

‘Hold on,’ Hannah said, strained. ‘Mum wants to talk to you.’

‘Hello, Paul.’

‘Mum, how are you?’ Stupid bloody question. And then she took him completely by surprise.

‘You of all my children know how I feel.’

It was the first time she’d openly acknowledged his grief for Belle. She must be feeling pretty dreadful, he thought. ‘Mum, what do you want me to do?’

‘Come home.’

‘I’ll be right there.’

She waited a beat. ‘But could you to do something for me first?’

‘Anything.’

‘I want you to get Dan out of Belmarsh.’

Something in his stomach squelched. ‘Mum, I really don’t—’

‘Please. I know what he did, but it was your father’s dying wish for Dan to be at his funeral.’

Always Dan, even to the last, he thought bitterly. The compassionate part of his nature was having a difficult time shining through, yet even he realised that Dan needed to be there as much as his old man had desired it. How the hell he was going to manage it was another story. Dan was in no ordinary prison for any ordinary offence. His only hope was Asim. ‘I’m not making any promises, but I’ll see if I can pull some strings.’

‘Thank you.’

They talked a little more. Now that he was home, they planned to go ahead with the funeral in five days’ time. To his surprise, his father was going to be cremated. Somehow Tallis had envisaged a full Catholic funeral, all bells and whistles. He had to remind himself that his mother was the religious one. His father never had much time for it. So much he hadn’t had time for.

‘You’ll let me know,’ she said, ‘about Dan.’

‘Soon as I can.’

Asim got to him first. Tallis was halfway down a bottle of fine malt whisky, all peat and bog, the taste suiting his mood, when Asim called. ‘The Moroccan was a guy known as Faraj Tardarti,’ Asim told him. ‘He’d trained at camps in Pakistan, was not considered to be a main player, although known to have contacts to those who were.’

‘Looks as though the Americans have a different take on him.’

‘He was on their watch list. Of more interest as far as Morello’s concerned,’ Asim continued, ‘two British men flew out of Heathrow to Istanbul and back again in the very twenty-four-hour period in which Morello was shot. Customs cottoned onto them because they were travelling light, and alerted the embassy.’

That prat Cardew, Tallis thought. Damn him and his blasted procedure. Either he didn’t make the connection or he was bought. ‘Names?’

‘Toby Beaufort and Tennyson Makepeace.’

What sort of names were those? ‘Having a laugh, were they?’

‘They were indeed.’

Forged passports.

‘Looks like they might be good for Morello’s murder,’ Asim said. ‘Must have picked up their gear the Turkish end.’

‘I’d say so. Still think there’s no connection between Morello and our Moroccan?’ Tallis couldn’t disguise the playful note in his voice.

‘Go on,’ Asim said, humouring him.

‘I went to visit Morello’s widow. She told me that Garry was working on a book exploring the link between organised crime and terrorism.’

‘Historically, there’s always been a link. Only have to look at the IRA.’

Asim could be so infuriating. ‘I don’t believe it was in a general sense,’ Tallis persisted. ‘Garry wanted to pick my brains, ask me about my patch, Birmingham, who the movers and shakers were. My take is that he was talking about current events. Gives more credence to what we already suspect.’

‘Birmingham, you say?’

‘Yes.’

Asim remained silent. Tallis assumed this to be a good sign. What he said was being taken seriously. ‘Maybe we should have left you at home.’

‘And deny me my two-night stay in a Turkish gulag?’ Tallis cracked.

‘Still got your contacts within the police?’

‘Some.’

‘Then maybe you should check out those movers and shakers.’

Tallis cut the call. It was only afterwards he remembered that he hadn’t asked Asim about Dan.

10

TALLIS had never been able to lie to his mother. ‘I simply don’t think it’s possible.’

He was back at home in Herefordshire. They’d spent the morning sitting in the little room they called the snug, going through the funeral arrangements. Hannah was forced to return home to Bristol for the kids. Her husband, a nice enough bloke in Tallis’s opinion, wasn’t a very handson dad. She promised to return with the rest of the family for the big send-off.

‘Take care of each other,’ Hannah said, tipping up on her toes to kiss them both. She didn’t really look like either of her parents. Small, with chestnut hair, she resembled more the photographs he’d seen of his grandmother as a young woman. As soon as Hannah left, his mother collared him.

‘Did you try?’ Her blue-grey eyes looked up into his brown.

‘Not yet.’ Shame made his neck flush. She’d been through so much, watching his father’s slow and lingering death. Then there’d been Dan and Belle. He didn’t want to let her down. And what was he really afraid of? That Dan would be allowed to come? That Dan would act in loco parentis? That all the fear and intimidation his father had visited on him would be transmitted through his evil elder brother? Or was he more frightened of his own reaction to seeing Dan again? He patted her hand gently. ‘But I will.’

After they’d eaten, she insisted on washing up the dishes immediately. He offered to help.

‘No need. Won’t take more than a few minutes.’

And so he went out into his mother’s garden, walked along the carefully created paths with the little bridge over the lily pond and, crossing to the far end, took out his mobile phone. As he looked back at the house, he remembered summer evenings watching the bats burst out, as in a hail of machine-gun fire, from underneath the eaves, dozens and dozens of baby horseshoes and pipistrelles.

Asim was sympathetic but not hopeful.

‘I’m not asking for me, but for my mum,’ Tallis pleaded. ‘You’re the only person who can swing it.’

Asim sounded doubtful about that, too. ‘When’s the funeral?’

‘Friday.’

‘I’ll get back to you,’ Asim promised.

Tallis spent the rest of the day with his mum. They talked of old times, laughing a little, avoiding the bad, which was easy. When two people remembered an event they generally viewed it in the context of their own personal narrative and prejudice. Staying the night was more taxing. He slept in the old room he’d shared with his brother, the same room in which he’d received taunts and beatings from his dad.

The next morning his mother announced that she wanted to go into town. Tallis offered to drive but she declined. ‘Time you went home.’

‘But I’ve only just arrived.’

‘Don’t you have work to go to?’ His parents had always had a strong work ethic, something they’d imbued into their kids. Tallis had led her to believe that he was some kind of private investigator, an occupation of which she disapproved. ‘I’ll be fine,’ she insisted.

‘But, Mum…’

She broke into a radiant smile, almost girlish. ‘I’d actually like to be alone.’

Hannah wouldn’t approve, he thought, standing there like a dumb animal.

‘Go,’ she said, giving him a gentle push in the middle of his chest.

Tallis looked into her face and found her impossible to read. He’d always worried that she’d go under when his father died, but he saw something else emergent, something strong. He thought it was hope, and envied her.

After picking up some basic supplies, Tallis got back home around noon. Jimmy next-door was still asleep. Apart from the fact the lad’s bedroom curtains were closed, neither property was being pulverised by sound.

Once inside, he picked up his mail, chucked it on a side table for later, stowed milk in the fridge, bread in the bread bin and made himself a pot of coffee. After that, he called Stu. They’d worked together as part of an elite group of undercover firearms officers. Stu had stayed on with the force after Tallis left, but after hitting the bottle had been returned to basic duties. Last time they’d spoken Stu had been in the process of kicking his addiction. He wasn’t finding it easy.

‘Hi, Stu, how are you doing?’

‘One hundred and twenty-one days and counting,’ Stu said morosely, his Glaswegian accent less pronounced since he’d packed in the booze.

‘That’s terrific.’

‘Fucking boring.’

Tallis let out a laugh. ‘You’ll just have to find some other addiction to float your boat.’

‘Yeah, but will it be legal?’

This was better. Even if everything was tits up, he could always rely on his mates to get him through. A sense of humour was essential to survival—especially in their line of work. ‘So what’s new on the old bush telegraph?’

‘Same old. Why?’

‘Ever have any contacts with the Serious and Organised Crime Agency?’

‘Must be joking. Wouldn’t sully themselves with the likes of us.’

‘So you’ve never come across a guy called Kevin Napier?’

‘Can’t say I have. Is he with SOCA?’

‘Recently promoted.’

‘No, it’s the Organised Crime lot SOCA have most contact with and even that’s carried out in darkened corridors.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘SOCA is extremely secretive. Have to be. They’re working against organised crime at the highest level. Most of us wouldn’t be able to get beyond a phone call to their press office.’

‘But I thought they worked closely with police on intelligence and operations at local level.’

‘They do. Every so often one of their officers swoop on Organised Crime, mix it up a bit then swoop back out again. We call them the free-range chickens of law enforcement agencies.’ Stu gave a low chuckle. ‘As you might imagine, their input isn’t always appreciated.’

An age-old problem, Tallis thought. Oh, he knew how it worked in theory: counter-terrorism was an amalgamation of police and security services, working side by side in a spirit of joint co-operation against a common foe, sharing intelligence, indivisible, one for all and all for one. However, the powers that be took little or no account of the frailty of human nature. When push came to shove, everyone ruthlessly guarded his or her own patch.

Stu was still banging on. ‘SOCA works at national level. They have the big picture. They know best, allegedly, patronising bastards.’

Add to that too many newly formed government agencies, too many new initiatives, way too many analysts, and nobody knowing what the hell they were doing, Tallis thought. More cynically, Tallis suspected the constant round of name changes was entirely deliberate. It was impossible to pinpoint who was running what. ‘So it’s a one-way street. SOCA gives the benefit of their expertise and fuck off. That right?’

Stu let out a raucous laugh. Tallis had no doubt that he’d pass that one on to a receptive ear. ‘I don’t suppose SOCA see it that way,’ Stu said, serious again. ‘I think they genuinely feel they’re doing their bit. In spite of some recent bad press, they are trying to get their act together. Problem was they were disadvantaged from the start.’

‘Because everyone had such high expectations?’ Tallis said.

‘That and because it takes time to build up intelligence. To be fair, they don’t openly trumpet success, but bearing in mind any local Organised Crime division knows its patch, exactly what’s going on, who’s doing what and where, it tends to have a bit of a pissing-off effect when the so-called elite muscle in.’

‘I don’t suppose you’d have a friendly contact whose ear I could bend?’

‘In Organised Crime?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Nick Oxslade,’ Stu said without a moment’s hesitation. ‘Great bloke. Came from the other side of the tracks same as me so I’ve got a lot of time for him. Can I ask why?’

‘You can ask,’ Tallis said enigmatically.

Stu gave another snort of mirth. ‘If they ever give that bloke playing Jason Bourne the chop…’

‘Matt Damon?’

‘That’s the one,’ Stu said. ‘I reckon you’d be a great replacement. After myself, of course.’

Tallis phoned the Proactive Crime Unit via the main number and then asked for an eight-digit extension. It had once been possible to contact an Organised Crime Officer direct via Lloyd House, the West Midlands Police Headquarters, but, since a number had received threatening phone calls from imprisoned villains they’d help put away, certain security measures had been put in place. Organised Crime Officers were no longer based there but at a number of secret addresses. Although Tallis wouldn’t be able to talk to Oxslade directly, he could leave a message for him to call back. On getting through, he was told that the entire department were busy on a major operation. He left a message anyway and then, undeterred, called another number, got straight through.

‘Bloody hell, the walking dead!’ There followed a cloudburst of coughing.

‘Waking dead,’ he corrected her, ‘and isn’t it time you packed in smoking?’ He imagined Crow sneaking out of her office, heading for a secret space not yet commandeered by the fag police. Their paths had crossed in his last investigation. Based in Camden, Detective Inspector Michelle Crow had proved an invaluable if slightly unconventional ally. She was big, butch looking and ballsy. She also had electric thinking.

‘And do what exactly?’ she scoffed, regaining her composure.

‘Breathe more easily?’

‘You sound like an advert for cough sweets. Look, you should be grateful. Once our merry little band have been exterminated, they’ll be turning the full spotlight on booze next…’

‘They already have. Don’t you read the newspapers?’

‘Try not to,’ she fired back, and returned to her main theme. ‘Then they’ll be banning sex.’

Tallis blinked. That D.I. Michelle Crow had sex with anyone had never occurred to him. Time to move on swiftly. ‘Reason I’m calling, Micky…’

‘Is because, unable to resist my womanly charms, you want to ask me out.’

‘I’d love to, darling.’ He cringed. ‘And next time I’m in London I will, but—’

‘You want to use me.’ She dropped her voice to a lascivious growl. Christ, what was she on? Tallis wondered, deeply regretting making the call. ‘Wish I could see your face.’ She burst out laughing. ‘So what can I really do you for?’

Tallis ignored the double entendre and ploughed on. ‘I need to know if two guys have sneaked within your radar. They go by the names of Toby Beaufort and Tennyson Makepeace.’

‘What did they do, steal someone’s poems?’

‘Killed a British journalist in Turkey.’

‘Straight up?’ A wily note had crept into Crow’s voice. Tallis imagined her chair creaking under the weight of her sizable rear.

‘Evidence pointing that way.’

‘Ah-hah,’ Crow said knowingly.

‘Obviously, this is all off the record.’

‘You need absolute discretion.’

‘Absolute.’

‘Strictly entre nous.’

Sod, that playful streak had crept back into her voice. ‘Yes.’

‘It will cost.’

He had been very much afraid of that. ‘I’m sure we can come to some agreement,’ he said neutrally.

‘I still haven’t forgotten being locked in your bloody toilet.’ It had been the only way to prevent her from getting involved in the action, he remembered.

‘I’m sure you haven’t,’ he said, closing his eyes. When he’d finally let her out, she’d charged at him like a wounded rhino.

‘Right, then,’ she said, businesslike. ‘I’ll see what I can turn up.’

The phone call from Oxslade, the Organised Crime Officer for whom he’d left a message, came through shortly before four in the afternoon. Tallis explained his contact with Stu. The mention of his old mate’s name worked like a magic charm. ‘I’m at the Forensic Science Service, waiting for a statement,’ Oxslade said, ‘but I could meet you later.’ He sounded bright and enthusiastic. How refreshing, Tallis thought. Oxslade suggested they meet at the Tarnished Halo on Ludgate Hill. Tallis knew that it was a popular haunt with the Fraud Squad so he proposed the White Swan in Harborne instead. This agreed, they arranged to meet at six that evening.

‘I’ll be wearing a brown leather jacket, jeans,’ Oxslade added, ‘and I’ve got short red hair.’

The rest of the afternoon was spent tackling the savannah outside and cutting it to more manageable proportions. Plants past rescue Tallis dug up and chucked onto an ever-increasing compost heap, the rest he weeded and fed with something out of a bottle that smelt mildly of antiseptic. By five, he was having his second shave of the day followed by a shower.

Instead of taking the car, he walked and caught a bus. It wasn’t far. He was still smarting from the earthquake and, though this minuscule change in lifestyle wouldn’t matter a damn in the great scheme of things, it made him feel more comfortable with himself.

The pub was already buzzing with early diners. Oxslade greeted him with an open expression. He was indeed redhaired and pink-faced and probably older than he looked. Already a third of the way down a pint, he asked Tallis what he was drinking. Tallis viewed the ales on tap and plumped for a pint of Banks. Eventually, they found a corner table far enough away from the clamour to hear but not be overheard. Tallis took a pull of his pint. Oxslade did the same and viewed Tallis with an expression bordering on awe.

‘Stu explained you once worked together.’

Stu would. ‘That’s right.’

Oxlade beamed. ‘I’ve often been asked if I thought my job was dangerous, you know when we take the big guys down? Know what my standard response is?’

Tallis didn’t. He shook his head.

‘I tell them we send the firearms officers in first to do the dirty stuff. We only waltz in once the offenders are trussed up like chickens.’

Tallis smiled, remembering.

‘Anyway,’ Oxslade said, ‘gather you want to talk about SOCA.’

‘Amongst other things.’

Oxslade grinned, leant forward conspiratorially. ‘We think of them as the blokes who write jokes for comedians.’

‘Yeah?’ Tallis grinned back.

‘They never receive the applause or the laughs.’

Different take to Stu, Tallis thought, sharing the joke. If Oxslade was right, he wouldn’t have thought Napier was that well suited to the job.

Oxslade took another drink. ‘Can I ask why the interest?’

‘I want to track someone I fought with during the first Gulf War.’ He asked if Oxslade knew Napier.

‘In passing. Not well.’

‘Was he advising on a particular operation?’

Oxslade smiled an apology.

‘It’s all right. Shouldn’t have asked.’ Tallis smiled back. He looked around the pub. Stylish interior. Good, friendly atmosphere. ‘Look, I’ll be straight with you, Nick.’ Tallis turned to him. ‘Since I left the force, I’ve gone into private investigation.’

Oxslade frowned. Tallis knew how Oxslade felt. PIs aroused the same high level of suspicion as journalists. ‘This connected to the reason you want to trace Napier?’

‘No, that’s entirely personal,’ Tallis lied. ‘My interest lies in the very people you referred to, the people I used to take down.’

‘Not sure I follow.’

Tallis flashed his best smile. Oxslade was privy to the massive database detailing all the active Mr Nastys. Of course he followed. ‘I remember there was this bloke in Wolverhampton. He had four different addresses, four different women, no meaningful employment and a great lifestyle. He was eventually tripped up through extensive examination of his business and financial transactions.’

‘The way we get a lot of these blokes now,’ Oxslade concurred.

‘I appreciate you can’t tell me who’s still in the game, but how about we play I Spy.’

‘You mean you name and I nod yes or no?’

‘Yup.’

Oxslade rolled his eyes. ‘You have to be joking.’

‘It’s not as though you’re telling me anything I don’t already know.’

‘Things have moved on.’ Yeah, Tallis knew. Road-traffic accidents were now referred to as collisions or incidents. Even the word ‘force’ had been substituted for ‘service’. However, some things never changed. ‘It’s much tighter,’ Oxslade said categorically. ‘I can’t tell you stuff like that.’