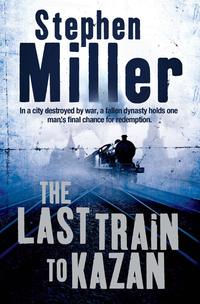

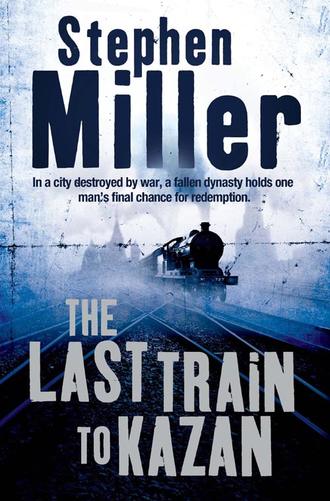

The Last Train to Kazan

Полная версия

The Last Train to Kazan

Жанр: приключениязарубежные приключенияисторическая литературасовременная зарубежная литературакниги о приключенияхсерьезное чтениеоб истории серьезно

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2018

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу