Полная версия

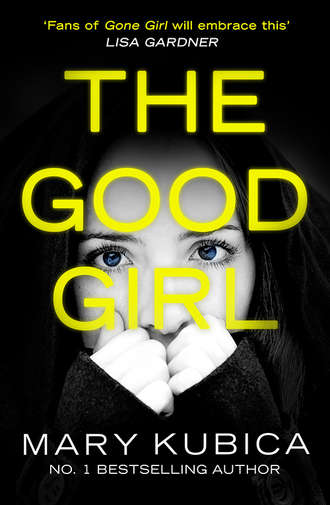

The Good Girl: An addictively suspenseful and gripping thriller

Mia looks up and sees me watching her. “Did you hear me, Mia?” I ask, my voice kind. She shakes her head, and I can all but hear the bothersome thought that runs through her mind: Chloe. My name is Chloe. Her blue eyes are glued to my own, which are red and watery from holding back tears, something that has become commonplace since Mia’s return, though as always James is there, reminding me to keep quiet. I try hard to make sense of it all, affixing a smile to my face, forced and yet entirely honest, and the unspoken words ramble through my mind: I just can’t believe you’re home. I’m careful to give Mia elbow room, not quite certain how much she needs, but absolutely certain I don’t want to overstep. I see her malady in every gesture and expression, in the way she stands, no longer brimming with self-confidence as the Mia I know used to be. I understand that something dreadful has happened to her.

I wonder, though, does she sense that something has happened to me?

Mia looks away. “We go back to see Dr. Rhodes next week,” I say and she nods in response. “Tuesday.”

“What time?” James asks.

“One o’clock.”

He consults his smartphone with a single hand, and then tells me that I will have to take Mia to the appointment alone. He says there is a trial, which he cannot miss. And besides, he says, he’s sure I can handle this alone. I tell him that of course I can handle it, but I lean in and whisper into his ear, “She needs you now. You’re her father.” I remind him that this is something we discussed and agreed to and how he promised. He says that he will see what he can do but the doubt weighs heavily on my mind. I can tell that he believes his unwavering work schedule does not allow time for family crises such as this.

In the backseat, Mia stares out the window watching the world fly by as we soar down I-94 and out of the city. It’s approaching three-thirty on a Friday afternoon, the weekend of the New Year, and so traffic is an ungodly mess. We come to a stop and wait and then inch forward at a snail’s pace, no more than thirty miles per hour on the expressway. James hasn’t the patience for it. He stares into the rearview mirror, waiting for the paparazzi to reappear.

“So, Mia,” James says, trying to pass the time. “That shrink says you have amnesia.”

“Oh, James,” I beg, “please, not now.”

My husband is not willing to wait. He wants to get to the bottom of this. It’s been barely a week since Mia has been home, living with James and me since she’s not fit to be on her own. I think of Christmas day, when the tired maroon car pulled sluggishly into the drive with Mia in tow. I remember the way James, nearly always detached, nearly always blasé, forced himself through the front door and was the first to greet her, to gather the emaciated woman in his arms on our snow-covered drive as if it had been him, rather than me, who spent those long, fearful months in mourning.

But since then, I’ve watched as that momentary relief shriveled away, as Mia, in her oblivion, became tiresome to James, just another one of the cases on his ever growing caseload rather than our daughter.

“Then when?”

“Later, please. And besides, that woman is a professional, James,” I insist. “A psychiatrist. She is not a shrink.”

“Fine then, Mia, that psychiatrist says you have amnesia,” he repeats, but Mia doesn’t respond. He watches her in the rearview mirror, these dark brown eyes that hold her captive. For a fleeting moment, she does her best to stare back, but then her eyes find their way to her hands, where she becomes absorbed in a small scab. “Do you wish to comment?” he asks.

“That’s what she told me, too,” she says, and I remember the doctor’s words as she sat across from James and me in the unhappy office—Mia having been excused and sent to the waiting room to browse through outdated fashion magazines—and gave us, verbatim, the textbook definition of acute stress disorder, and all I could think of were those poor Vietnam veterans.

He sighs. I can tell that James finds this implausible, the fact that her memory could vanish into thin air. “So, how does it work, then? You remember I’m your father and this is your mother, but you think your name is Chloe. You know how old you are and where you live and that you have a sister, but you don’t have a clue about Colin Thatcher? You honestly don’t know where you’ve been for the past three months?”

I jump in, to Mia’s defense, and say, “It’s called selective amnesia, James.”

“You’re telling me she picks and chooses things she wants to remember?”

“Mia doesn’t do it—her subconscious or unconscious or something like that is doing it. Putting painful thoughts where she can’t find them. It’s not something she’s decided to do. It’s her body’s way of helping her cope.”

“Cope with what?”

“The whole thing, James. Everything that happened.”

He wants to know how we fix it. This, I don’t know for certain, but I suggest, “Time, I suppose. Therapy. Drugs. Hypnosis.”

He scoffs at this, finding hypnosis as bona fide as amnesia. “What kind of drugs?”

“Antidepressants, James,” I respond. I turn around and, with a pat on Mia’s hand, say, “Maybe her memory will never come back and that will be okay, too.” I admire her for a moment, a near mirror image of myself, though taller and younger and, unlike me, years and years away from wrinkles and the white locks of hair that are beginning to intrude upon my mass of dirty blond.

“How will antidepressants help her remember?”

“They’ll make her feel better.”

He is always entirely candid. This is one of James’s flaws. “Well hell, Eve, if she can’t remember then what’s there to feel bad about?” he asks and our eyes stray out the windows at the passing traffic, the conversation considered through.

Gabe

Before

The high school where Mia Dennett teaches is located on the northwest side of Chicago in an area known as North Center. It’s a relatively good neighborhood, close to her home, a mostly Caucasian population with an average monthly rent over a thousand dollars. This all bodes well for her. If she was working in Englewood I wouldn’t be so sure. The purpose of the school is to provide an education to high school dropouts. They offer vocational training, computer training, life skills, et cetera, in small settings. Enter Mia Dennett, the art teacher, whose purpose is to add the nontraditional flair that’s been taken out of traditional high schools, those needing more time for math and science and to bore the hell out of sixteen-year-old misfits who couldn’t give a damn.

Ayanna Jackson meets me in the office. I have to wait a good fifteen minutes for her because she’s in the middle of class, and so I squeeze my body onto one of those small emasculating plastic school chairs and wait. This is something that certainly does not come easy to me. I’m far from the six-pack of my former days, though I like to think I wear the extra weight well. The secretary keeps her eyes locked on me the entire time as if I’m a student sent down to have a chat with the principal. This is a scene with which I’m sadly accustomed, many of my high school days spent in this very predicament.

“You’re trying to find Mia,” she says as I introduce myself as Detective Gabe Hoffman. I tell her that I am. It’s been nearly four days since anyone has seen or spoken to the woman and so she’s been officially designated as missing, much to the judge’s chagrin. It’s been in the papers, on the news, and every morning when I roll out of bed I tell myself that today will be the day I find Mia Dennett and become a hero.

“When’s the last time you saw Mia?”

“Tuesday.”

“Where?”

“Here.”

We make our way into the classroom and Ayanna—she begs me not to call her Ms. Jackson—invites me to sit down on one of those plastic chairs attached to the broken, graffiti-covered desk.

“How long have you known Mia?”

She sits at her desk in a comfy leather chair and I feel like a kid, though in reality, I top her by a good foot. She crosses her long legs, the slit of a black skirt falling open and exposing flesh. “Three years. As long as Mia’s been teaching.”

“Does Mia get along with everyone? The students? Staff?”

She’s solemn. “There’s no one Mia doesn’t get along with.”

Ayanna goes on to tell me about Mia. About how, when she first arrived at the alternative school, there was a natural grace about her, about how she empathized with the students and behaved as if she, too, had grown up on the streets of Chicago. About how Mia organized fundraisers for the school to pay for needy students’ supplies. “You never would have known she was a Dennett.”

According to Ms. Jackson, most new teachers don’t last long in this type of educational setting. With the market the way it is these days, sometimes an alternative school is the only place hiring and so college grads accept the position until something else comes along. But not Mia. “This was where she wanted to be.

“Let me show you something,” she says and she pulls a stack of papers from a letter tray on her desk. She walks closer and sits down on one of the student desks beside me. She sets the mound of paper before me and what I see first is a scribble of bad penmanship, worse than my own. “This morning the students worked on their journal entries for the week,” she explains and as my eyes peruse the work, I see the name Ms. Dennett more times than I can count.

“We do journal entries each week. The assignment this week,” she explains, “was to tell me what they wanted to do with themselves after high school.” I mull this over for a minute, seeing the words Ms. Dennett splattered over almost every sheet of paper. “But ninety-nine percent of the students are thinking of nothing but Mia,” she concludes, and I can hear, by the dejection in her voice, that she, too, can think of little but Mia.

“Did Mia have trouble with any of the students?” I ask, just to be sure. But I know what her answer is going to be before she shakes her head.

“What about a boyfriend?” I ask.

“I guess,” she says, “if you could call him that. Jason something-or-other. I don’t know his last name. Nothing serious. They’ve only been dating a few weeks, maybe a month, but no more.” I jot this down. The Dennetts made no reference to a boyfriend. Is it possible they don’t know? Of course it’s possible. With the Dennett family, I’m beginning to learn, anything is possible.

“Do you know how to get in touch with him?”

“He’s an architect,” she says. “Some firm off Wabash. She meets him there most Friday nights for happy hour. Wabash and...I don’t know, maybe Wacker? Somewhere along the river.” Sounds like a wild-goose chase to me, but I’m up for it. I make note of this information in my yellow pad.

The fact that Mia Dennett has an elusive boyfriend is great news for me. In cases like this, it’s always the boyfriend. Find Jason and I’m sure to find Mia as well, or what’s left of her. Considering she’s been gone for four days, I’m starting to think this story might have an unhappy ending. Jason works by the Chicago River: bad news. God knows how many bodies are pulled out of that river every year. He’s an architect, so he’s smart, good at solving problems, like how to discard a hundred-and-twenty-pound body without anyone noticing.

“If Mia and Jason were dating,” I ask, “is it odd that he isn’t trying to find her?”

“You think Jason might be involved?”

I shrug. “I know if I had a girlfriend and I hadn’t spoken to her in four days, I might be a little concerned.”

“I guess,” she agrees. She stands from the desk and begins to erase the chalkboard. It leaves tiny remnants of dust on her black skirt. “He didn’t call the Dennetts?”

“Mr. and Mrs. Dennett have no idea that there’s a boyfriend in the picture. As far as they’re concerned, Mia is single.”

“Mia and her parents aren’t close. They have certain...ideological differences.”

“I gather that.”

“I don’t think it’s the kind of thing she’d tell them.”

The topic is drifting, so I try to reel Ayanna back in. “You and Mia are close, though.” She says that they are. “Would you say that Mia tells you everything?”

“As far as I know.”

“What does she tell you about Jason?”

Ayanna sits back down, this time on the edge of her desk. She peers at a clock on the wall, dusts off her hands. She considers my question. “It wasn’t going to last,” she tells me, trying to find the right words to explain. “Mia doesn’t become involved too often, never anything serious. She doesn’t like to be tied down. Committed. She’s markedly independent, perhaps to a fault.”

“And Jason is...clingy? Needy?”

She shakes her head. “No, it’s not that, it’s just, he’s not the one. She didn’t glow when she spoke of him. She didn’t gossip like girls do when they’ve met the one. I always had to force her to tell me about him and then, it was like listening to a documentary: we went to dinner, we saw a movie.... And I know his hours were bad, which irritated Mia—he was always missing dates or showing up late. Mia hated to be tied down to his schedule. You have that many issues in the first month and it’s never going to last.”

“So it was possible Mia was planning to break up with him?”

“I don’t know.”

“But she wasn’t entirely happy.”

“I wouldn’t say Mia wasn’t happy,” Ayanna responds. “I just don’t think she cared one way or the other.”

“From what you know, did Jason feel the same?” She says that she doesn’t know. Mia was rather aloof when she spoke of Jason. The conversations were nondescript: a checklist of things they had done that day, details of the man’s statistics—height, weight, hair and eye color—though remarkably, no last name. But Mia never mentioned if they kissed and there was no reference to that tingly feeling in the pit of your stomach—Ayanna’s words, not mine—when you’ve met the man of your dreams. She seemed upset when Jason stood her up—which, by Ayanna’s account, happened often—and yet she didn’t seem particularly excited on the nights they planned a late-night rendezvous down by the Chicago River.

“And you’d characterize this as disinterest?” I ask. “In Jason? The relationship? The whole thing?”

“Mia was passing time until something better came along.”

“Did they fight?”

“Not that I know of.”

“But if there was a problem, Mia would have told you,” I suggest.

“I’d like to think she would have,” the woman responds, her dark eyes becoming sad.

A bell rings in the distance, followed by the clatter of footsteps in the hall. Ayanna Jackson rises to her feet, which I take as my cue. I say that I’ll be in touch and leave her with my card, asking that she call if anything comes to mind.

Eve

After

I’m halfway down the stairs when I see them, a news crew on the sidewalk before our home. They stand, shivering, with cameras and microphones; Tammy Palmer from the local news in a tan trench coat and knee-high boots on my front lawn. Her back is toward me, a man counting down on his fingers—three...two...—and as he points at Tammy I all but hear her broadcast begin. I’m standing here at the home of Mia Dennett....

This isn’t the first time they’ve been here. Their numbers have begun to dwindle now, their reporters moving onto other stories: same-sex marriage laws and the dismal state of the economy. But in the days after Mia’s return they were camped outside, desperate for a glimpse of the damaged woman, for any morsel of information to turn into a headline. They followed us around town in their cars until we all but locked Mia inside.

There have been mysterious cars parked outside, photographers for those trashy magazines peering out of car windows with their telephoto lenses, trying to turn Mia into a cash cow. I pull the drapes closed.

I spot Mia sitting at the kitchen table. I descend the stairs in silence, to watch my daughter in her own world before I intrude upon it. She’s dressed in a pair of ripped jeans and a snug navy turtleneck that I bet makes her eyes look just amazing. Her hair is damp from an earlier shower, drying in waves down her back. I’m addled by the thick wool socks that blanket her feet, that and the mug of coffee her hands are united around.

She hears me approach and turns to look. Yes, I think to myself, the turtleneck makes her eyes look amazing.

“You’re drinking coffee,” I say, and it’s the vague expression on her face that makes me certain I’ve said the wrong thing.

“I don’t drink coffee?”

I’ve been treading carefully for over a week now, always trying to say the right thing, going over-the-top—ridiculously so—to make her feel at home. I’ve been on edge to compensate for James’s apathy and Mia’s disarray. And then, when least expected, a seemingly benign conversation, and I slip up.

Mia doesn’t drink coffee. She doesn’t drink much caffeine at all. It makes her nervous. But I watch her sip from the mug, completely stagnant and sluggish, and think—wish—that maybe a little caffeine will do the trick. Who is this limp woman before me, I wonder, recognizing the face but having no knowledge of the body language or tone of voice or the disturbing silence that encompasses her like a bubble.

There are a million things I want to ask her. But I don’t. I’ve vowed to just let her be. James has pried more than enough for the both of us. I’ll leave the questions to the professionals, Dr. Rhodes and Detective Hoffman, and to those who just never know when to quit—James. She’s my daughter, but she’s not my daughter. She’s Mia, but she’s not Mia. She looks like her, but she wears socks and drinks coffee and wakes up sobbing in the middle of the night. She’s quicker to respond if I call her Chloe than when I call her by her given name. She looks empty, appears asleep when she’s awake, lies awake when she should be asleep. She nearly flew three feet from her seat when I turned on the garbage disposal last night and then retreated to her room. We didn’t see her for hours and when I asked how she passed the time all she could say was I don’t know. The Mia I know can’t sit still for that long.

“It looks like a nice day,” I offer but she doesn’t respond. It does look like a nice day; it’s sunny. But the sun in January is deceiving and I’m certain the earth will warm to no more than twenty degrees.

“I want to show you something,” I say and I lead her from the kitchen to the adjoining dining room, where I’ve replaced a limited edition print with one of Mia’s works of art, back in November when I was certain she was dead. Mia’s painting is done in oil pastels, this picturesque Tuscan village she drew from a photograph after we visited the area years ago. She layered the oil pastels, creating a dramatic representation of the village, a moment in time trapped behind this sheet of glass. I watch Mia eye the piece and think to myself: If only everything could be preserved that way. “You made that,” I say.

She knows. This she remembers. She recalls the day she set herself down at the dining room table with the oil pastels and the photograph. She had begged her father to purchase the poster-board for her and he agreed, though he was certain her newfound love of art was only a passing phase. When she was finished we all oohed and ahhed and then it was tucked away somewhere with old Halloween costumes and roller skates only to be stumbled upon later on a scavenger hunt for photographs of Mia that the detective asked us to collect.

“Do you remember our trip to Tuscany?” I ask.

She steps forward to run her lovely fingers over the work of art. She stands inches above me, but in the dining room she is a child—a fledgling not yet sure how to stand on her own two feet.

“It rained,” Mia responds without removing her eyes from the drawing.

I nod. “It did. It rained,” I say, glad that she remembered. But it rained only one day and the rest of the days were a godsend.

I want to tell her that I hung the drawing because I was so worried about her. I was terrified. I lay awake night after night for months on end just wondering, What if? What if she wasn’t okay? What if she was okay but we never found her? What if she was dead and we never knew? What if she was dead and we did know, the detective asking us to identify decaying remains?

I want to tell Mia that I hung her Christmas stocking just in case and that I bought her presents and wrapped them and put them under the tree. I want her to know that I left the porch light on every night and that I must have called her cell phone a thousand times just in case. Just in case one time it didn’t go straight to the voice mail. But I listened to the message over and over again, the same words, the same tone—Hi, this is Mia. Please leave a message—allowing myself to savor the sound of her voice for a while. I wondered: what if those were the last words I ever heard from my daughter? What if?

Her eyes are hollow, her expression vacant. She has the most unflawed peaches-and-cream complexion I believe I’ve ever seen, but the peaches seemed to have disappeared and now she is all cream, white as a ghost. She doesn’t look at me when we speak; she looks past me or through me, but never at me. She looks down much of the time, at her feet, her hands, anything to avoid another’s gaze.

And then, standing there in the dining room, her face drains of every last bit of color. It happens in an instant, the light seeping through the open drapes highlighting that way Mia’s body lurches upright and then sags at the shoulders, her hand falling from the image of Tuscany to her abdomen in one swift movement. Her chin drops to her chest, her breathing becomes hoarse. I lay a hand on her skinny—too skinny, I can feel bones—back and wait. But I don’t wait long; I’m impatient. “Mia, honey,” I say, but she’s already telling me that she’s okay, she’s fine, and I’m certain it’s the coffee.

“What happened?”

She shrugs. Her hand is glued to the abdomen and I know she doesn’t feel well. Her body has begun a retreat from the dining room. “I’m tired, that’s all. I just need to go lie down,” she says and I make a mental note to rid the house of all traces of caffeine before she wakes up from her nap.

Gabe

Before

“You’re not an easy man to find,” I say as he welcomes me into his work space. It’s more of a cubicle than an office, but with higher walls than normal, offering a minimal amount of privacy. There’s only one chair—his—and so I stand at the entrance to the cube, cocked at an angle against the pliable wall.

“I didn’t know someone was trying to find me.”

My first impression is he’s a pompous ass, much like myself years ago, before I realized I was more full of myself than I should be. He’s a big man, husky, though not necessarily tall. I’m certain he works out, drinks protein shakes, maybe uses steroids? I’ll jot this down in my notes, but for now, I’d hate to have him catch me making these assumptions. I might get my ass kicked.

“You know Mia Dennett?” I ask.

“That depends.” He turns around in his swivel chair, finishes typing an email with his back to me.

“On what?”

“On who wants to know.”

I’m not too eager to play this game. “I do,” I say, saving my trump card until later.

“And you are?”

“Looking for Mia Dennett,” I respond.

I can see myself in this guy, though he can barely be twenty-four or twenty-five years old, just out of college, still believing the world rotates around him. “If you say so.” I, however, am on the cusp of fifty, and just this morning noticed the first few strands of gray hair. I’m certain I have Judge Dennett to thank for them.

He continues the email. What the hell, I think. He couldn’t care less that I’m standing here, waiting to talk to him. I peer over his shoulder to have a look. It’s about college football, sent to a recipient by the user name dago82. My mother is Italian—hence the dark hair and eyes I’m certain all women are wooed by—and so I take the derogatory name as an insult against my people, though I’ve never been to Italy and don’t know a single word in Italian. I’m just looking for another reason not to like this guy. “Must be a busy day,” I comment and he seems peeved that I’m reading his email. He minimizes the screen.