Полная версия

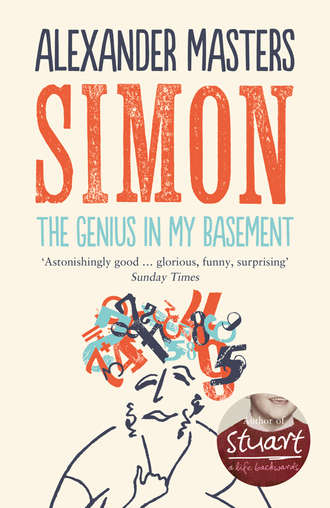

The Genius in my Basement

ALEXANDER MASTERS

The Genius in my Basement

The biography of a happy man

Dedication

For gorgeous Flora

Oh dear, I have a feeling this book

is going to be a disaster for me.

Simon Norton

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

1

2 The reader meets Simon

Minus N

4

5

*6 The Monster

*7

45

9 eSimon

10 Mars

*11

12

*13

14

15

16 Simon Cuttlefish

*17

18

19

20 Eton

*21 3D chess

*22 Breakthrough

23 Breakdown!

24

*25 How to bag a Subgroup

26

*27 Garbage Bag Group

28

29 Great Silence

30

*31 The Monster

32 Atlas

33

34

*35 Moonshine

36 Discovery!

37

38

Acknowledgements

Further Reading

Also by Alexander Masters

Copyright

About the Publisher

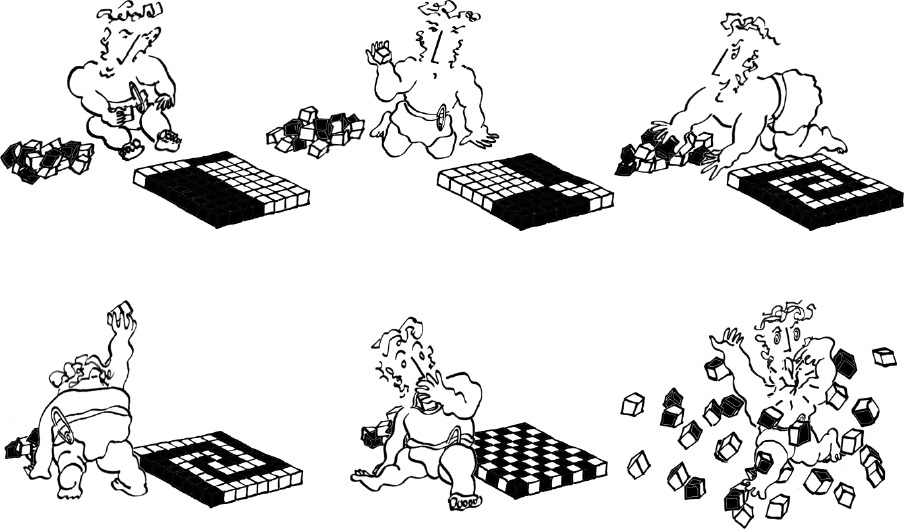

1

Simon was one year old, playing in the dining room, getting under his mother’s stilettos.

He was unusually thoughtful. His brothers at this age pounded the toy blocks on the glass coffee table and jabbed them into the electric sockets.

Simon picked up a pink block from the pile beside his knee and smoothed it against the carpet. Carefully, he positioned a blue brick alongside. He reached across – his mother, on her way to lay the side-plates and forks, had to make a sharp swerve – for two more pink bricks, and slid them against the blue. With precision, he extracted another blue brick.

Shuffling across the room on his bottom, Simon found four more pink bricks, fumbled them back and continued the arrangement.

His mother, halfway through folding napkins into bishops’ mitres, stopped in astonishment. She saw at last what he was doing.

One blue, one pink.

One blue, two pinks.

One blue, three pinks.

One blue, four pinks.

From the disarray of Nature, her baby son was enforcing regularity.

It took our species from the birth of prehistory to the dawn of Babylonian civilisation to learn mathematics.

Simon was bumping about its foothills in just over twelve months.

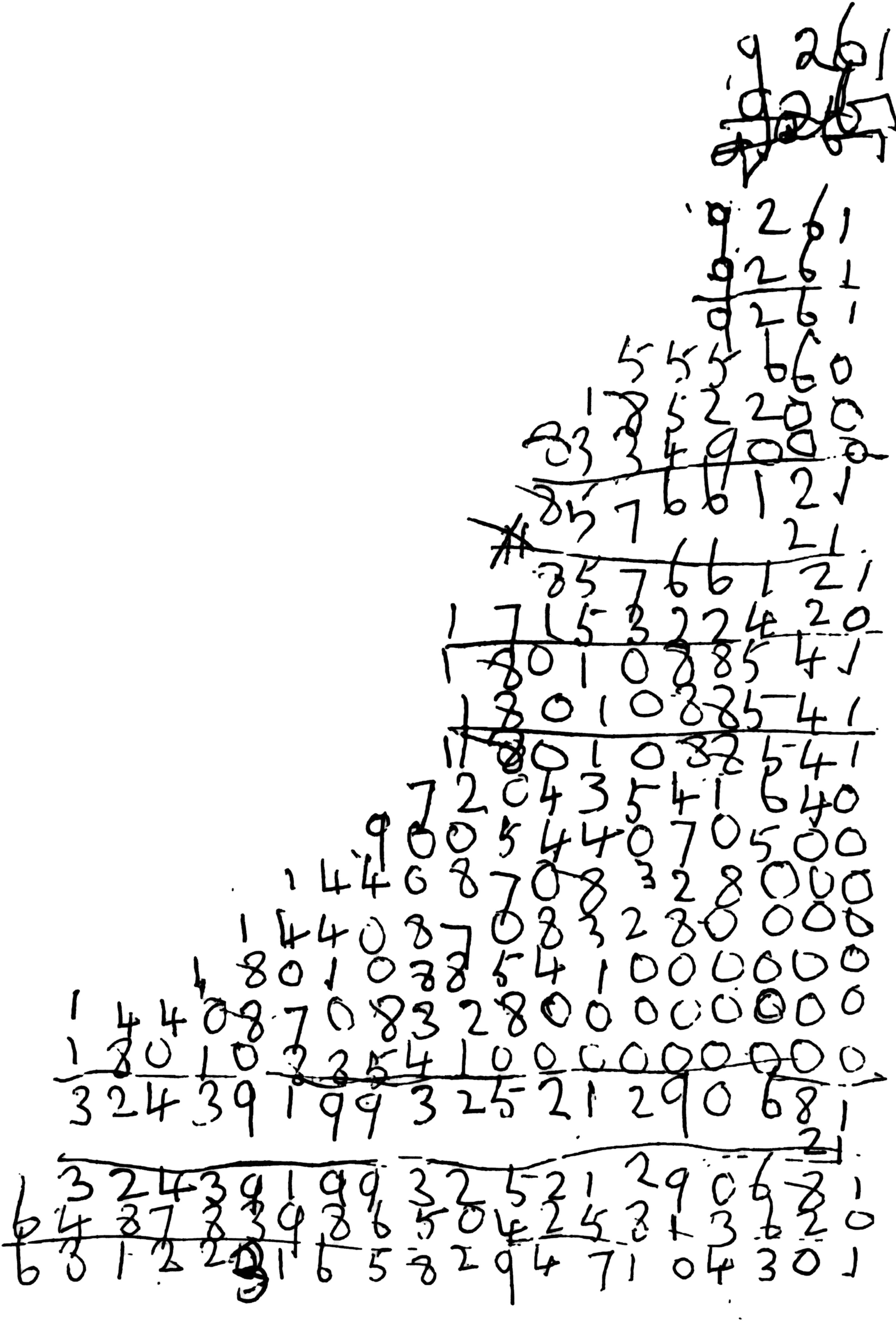

At three years, eleven months and twenty-six days, he toddled into cake-layers of long multiplication:

(January 1956)

Simon’s brother Francis had barely managed to recite the digits from one to ten by the time he was four years old; his brother Michael, a fraction quicker, had understood that if you gave him three banana-flavour milkshakes, and asked him to ‘count’ them, the correct answer was ‘one’ for the first, ‘two’ for the second and ‘three’ for the sticky splosh dribbling down his ear.

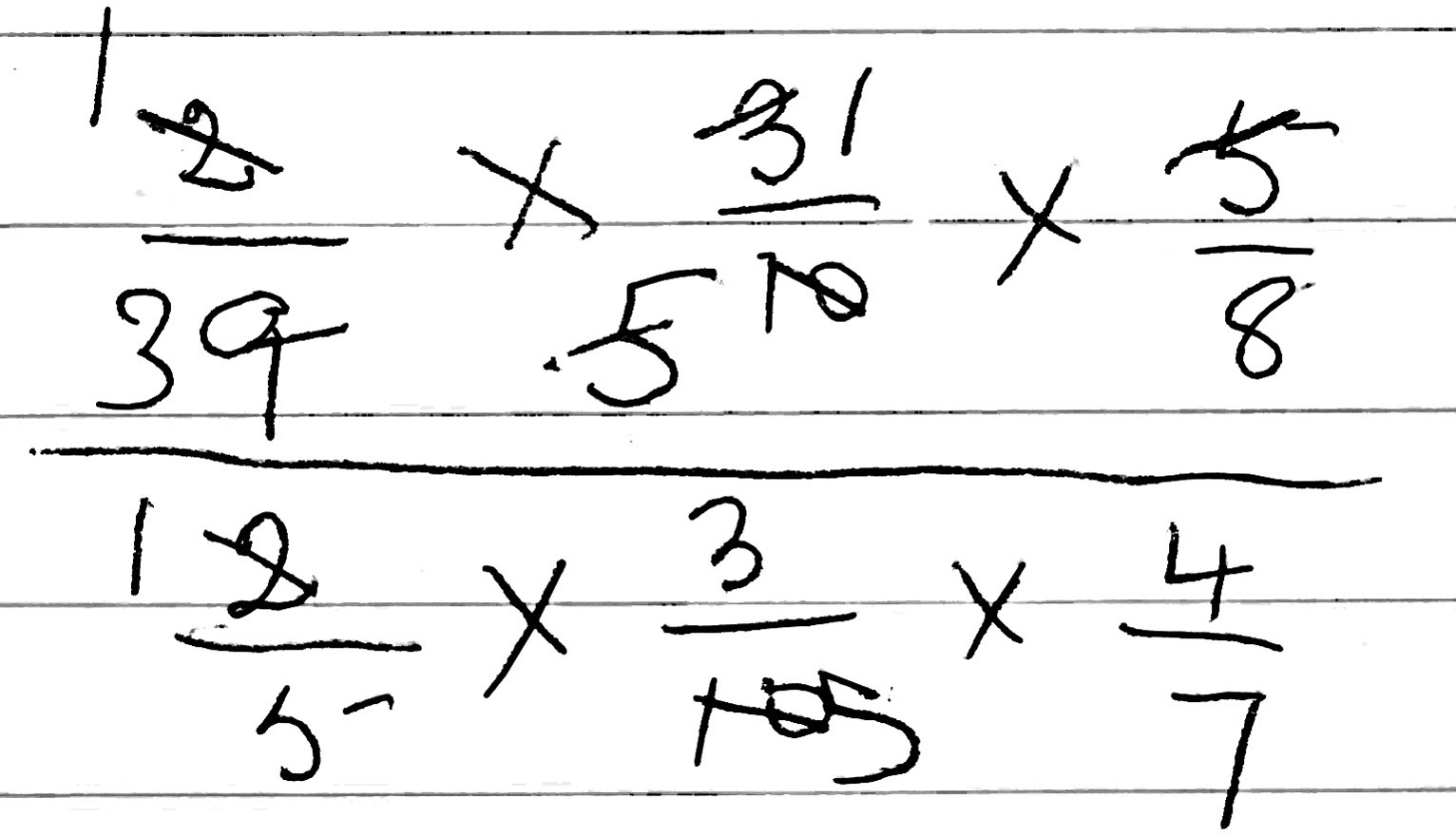

Percentages, square numbers, factors, long division, his 81 and 91 times tables, making numbers dance about to itchy tunes:

Simon mastered these when he was five.

Occasionally, his attention wandered:

2 The reader meets Simon

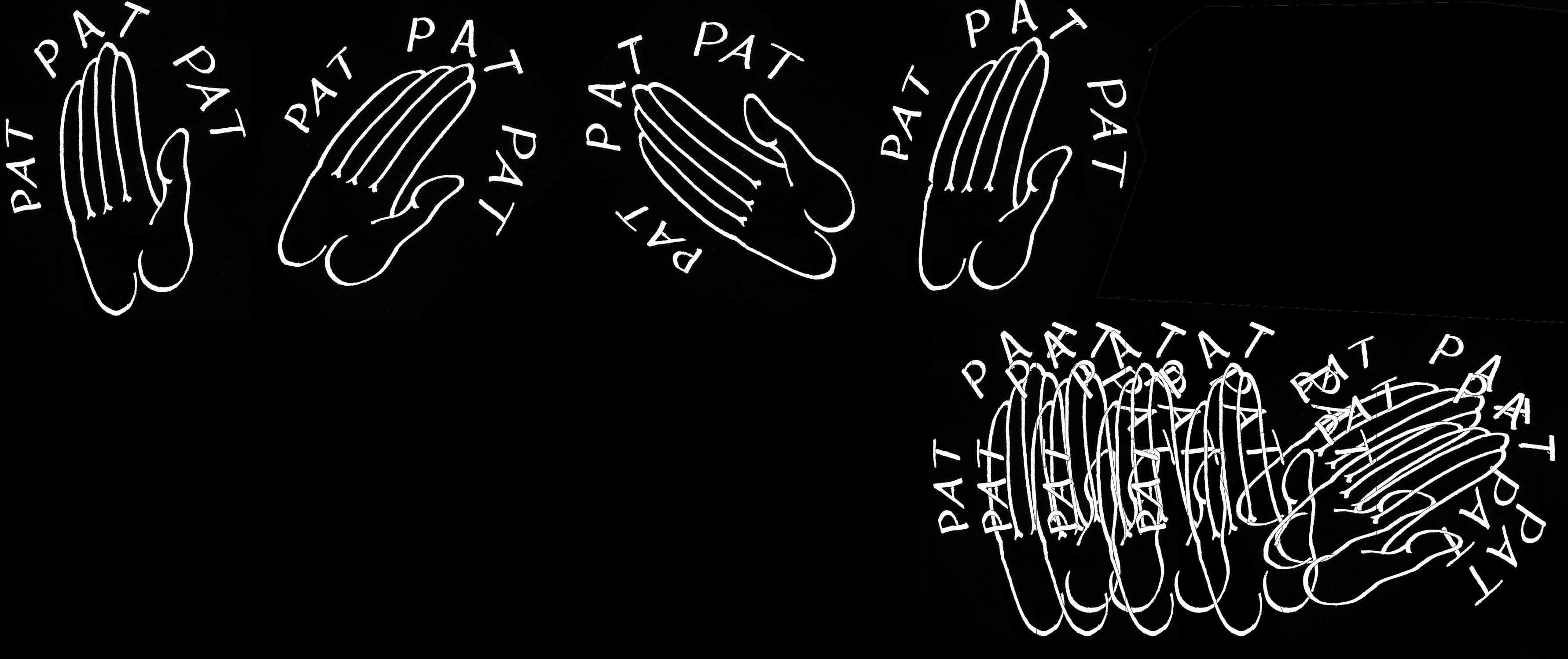

Sschliissh, dhuunk, dhuunk, zwaap, dhuunk, zwaap …

Listen! Can you hear?

… dhuunk, sschliissh, dhuunk, zaap, zwap, dhuunk … Bend down. Put your ear against the carpet: Zwaap, dhuunk, dhuunk, dhuunk,

zwaap, dhuunk, ssschliissh …

It’s fifty years later.

… liissh, dhuunk, dhuunk, dhuunk, zwaap, dhuunk, ssschliissh, dhunnk dhuunk, zwa ap, sclissh dhunnk, du unnk, sw

That’s the sound of a once-in-a-generation genius.

Simon Phillips Norton: Phillips, with an ‘s’, as if one Phillip were not enough to contain his brilliance. He lives under my floorboards.

Dhuunk, dhuunk …

When I first moved here, I had no idea what the noises were. Underground rivers? The next-door neighbours dragging a new pot through to their Tuscan garden? Dhuunk, dhuunk … But after eight years of interpretation I know that it’s the great man’s feet, stomping from one end of his room to the other. Every second stomp is heavier.

‘Sssschlissh’: that’s the swipe of his puffa ski-jacket against the stalagmites of paperbacks he keeps piled on the furniture.

‘Zwaap’: the sound of his holdall, as he rotates at the end of the room. He sometimes flings it wide, hitting papers. Simon carries this bag about with him everywhere he goes, clutched in the crook of his arm, even if it’s just to his front door to let in the gas man.

… dhuunk, dhuunk, dhuunk, zwaap, dhuunk, dhuunk …

Simon’s bed is ten feet directly beneath mine. My study is on top of his living room. His stomping space extends the full depth of the building, under my floor. My balcony is the roof of his basement extension, which has herded all the pretty garden plants into a six-foot square at the back of our house and stamped them under concrete slabs.

The phone rings. A charge from Simon: Dhuunk! Dhuunk! Dhuunk!

Snorting. The receiver – … rrinng, clank, clumpump, ping, ping … – wrenched from its holster. Attempts at speech, grunts, bangs of talk-noise; a strangulated word.

Clunk. Phone back in its holster.

Silence.

Dhuunk, dhuunk, dhuunk …

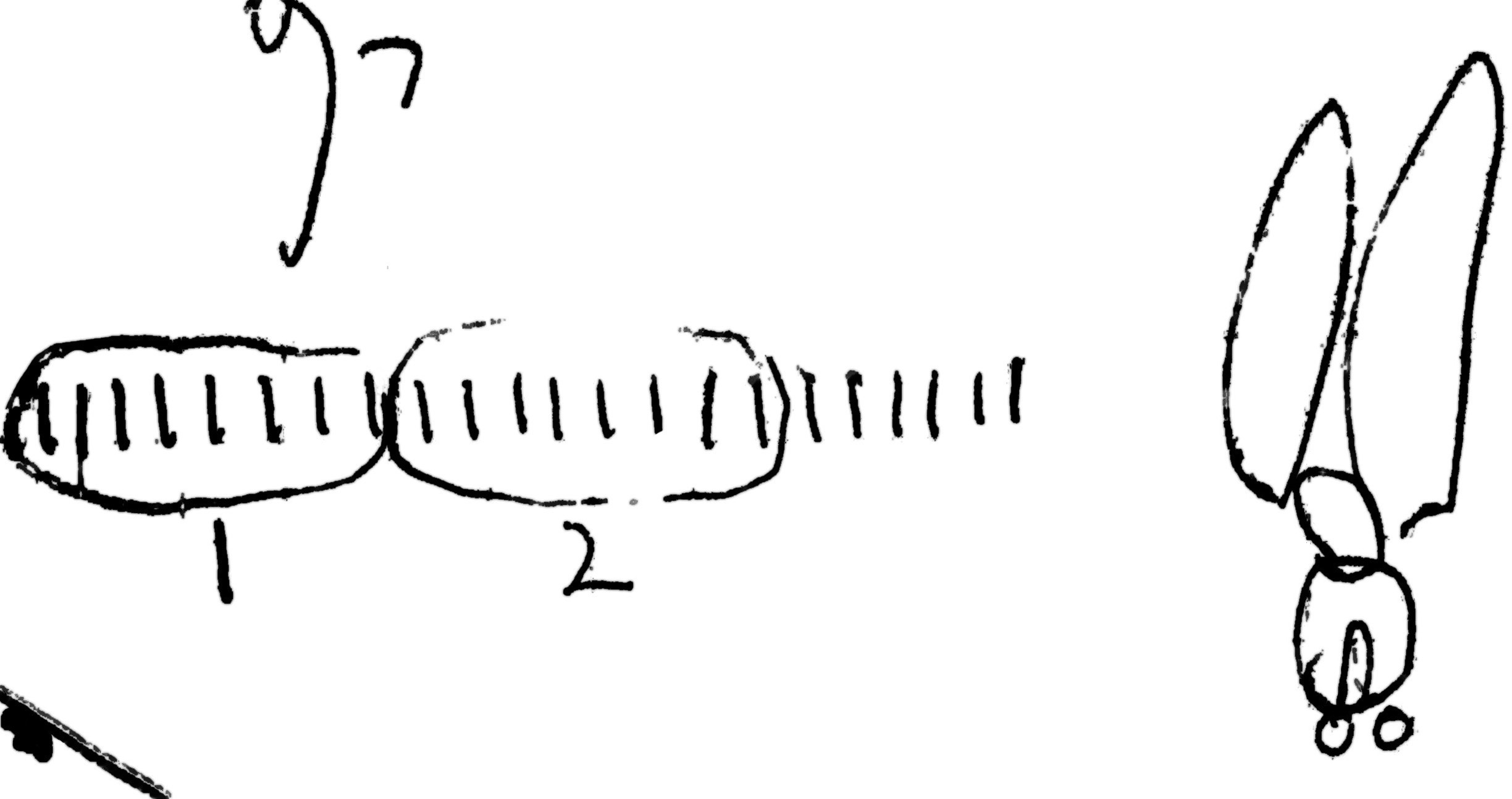

There’s another very important sound, which is too difficult to represent typographically: an intermittent, twisted crackle, sharp but thick, with a strong sense of command, resting on a base of plosive disorder. In an exercise book from when he was five there’s a squiggle that comes close:

It’s the sound of plastic-bag-being-opened-in-a-hurry-andthe-gratification-of-discovering-important-papers-inside. Without understanding this noise, you cannot understand the man.

… ssschliissh, dhuunk, zwaap, zwaap, dhuunk, dhuunk … Simon has been pacing down there for twenty-seven years, three months, five days, thirteen hours and eight minutes.

Ssssh!

Stop breathing!

Did you catch that?

Still another sort of noise?

A sort of sigh?

That was a thought.

Minus N

Your representation of me as interesting is

inaccurate. I feel ashamed by it.

Simon

Damn! He’s gone!

Simon’s refused to enter the book!

He is a Minus Norton. ‘Why now?’ I demanded, jumping up from the carpet when he stomped into my study from the basement. ‘The reader has started the story. He’s spent the money. He feels conned.’

‘How do you know it’s a he who’s reading it? It might be a she, hnnn.’

‘He or she! Who cares?’

‘I presume they do,’ he said cunningly.

Behind him, a bubble of air floated up the stairs and expanded into my rooms of the house, whiffing of damp and sardines.

Then he barged out of the front door, and, the scuff of his sandals becoming rapidly soft and seaside-ish, disappeared towards the Mathematics Faculty.

A book about Simon that doesn’t have Simon in it?

I had thought a life of Simon would be tiptoeing on the edge of the shadow of God. Instead, he crashes about my study as though heel-joints had never been invented; makes women shriek when they turn on the light in the corridor and find him standing there like an Easter Island statue; his holdall twists him into animal shapes; he hides behind envelopes.

He shocks me awake with his snores.

Writing biographies of living people, the subject is an irritant. Why is he needed? All he does is insist that whatever you’ve written is wrong.

In fact, when Simon was part of the book, I had to run away from him.

Wouldn’t all biographies be better if they gave up trying to fix the person they’re writing about, and confined themselves to his glints and reflections – not a biography of Simon, but of the perception of Simon? What is a biography, anyway? A platter of gossip and titbits. It’s up to the readers to mix these components together in whatever way they find most entertaining and instructive. The subject’s out of it. Once word hits page, he’s irrelevant.

I’m glad Simon’s gone. Good riddance!

In mathematics, you jump onto the subject of numbers through your experience of reality – two flies multiplied by four sudden pulls gives eight wings; three toads, two frogs and one bathtub equals six screams of fury from your father; four bags of crisps and five of your mum’s fags make nine orders of stomach ache – that’s how the newcomer gets introduced to the subject, via the positive, whole numbers: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 …

But mathematicians insist that negative numbers are equally real. It’s just a matter of which way you happen to look: going ahead is positive, and going behind is negative.

I’ll go behind Simon. Allow me to introduce Biographical Minus N:

Simon Phillips MINUS Norton.

Now, let’s break into his basement.

4

26th November 1922: Carter pierced a small hole in the wall through which he could look into the Pharaoh’s chamber with a sliver of torch light. Asked if he could see anything he replied, ‘yes, wonderful things!’

Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb

But I can’t find the light switch.

Which is important when you’re standing at the top of Simon’s stairs with nothing but sardine stench and book-writer’s bones to break your fall. Every other house in our terrace has a light switch by the stairwell door – why has Simon wrenched his out?

It makes me tense. My nerves clench into a knot. It feels planned.

There are holes in the stair carpet: lips of fabric at the edge of the treads, cut to flop forward, snatch … tap-tap … your toes …

… and plunge you onto the quarry tiles at the bottom.

These stairs are booby-trapped – against biographers.

Phhuuuuh! What was that? A moth? No. Just a grease dollop drifting by. Unidentified species often float up this stairwell.

It’s safest to take the rest of the steps spreadeagle fashion, one foot slithering against the wall while the other rat-a-tats along the bannister spindles. The palms of my hands catch and release on splodges of stickiness. As I slide down, I pass over two treads that have been blasted away. The wood has been broken in. It’s a sheer drop between the thigh-shredding splinters left behind to the floor below. Craftily, Simon has left the carpet in place over the chasm.

The only person who has been caught by this booby trap is the booby who manufactured it in the first place, Dr Simon MINUS Norton. The other week, I remember, I saw him leaping about the street on one leg, clutching his knee.

At last, here, at the bottom of the steps, we encounter a switch …

The bulb – low-watt, energy-saving – spreads shadow, not light.

It gathers a narrow entrance lobby into view, the floor of which is strewn with woodshavings and brick fragments. Sections of plaster have chipped away from the walls, exposing shoddy Victorian masonry. Along one edge of one side of the carpet is a pile of merry-coloured supermarket bags – perhaps forty in total, traffic-light orange, Pacific blue, lime-green stripes – the plastic straining colonically against the mass of paperwork rammed inside.

If we squeeze over the rubble and past these plastic bags, we can peer through a door frame that appears to have lost its door. Wrinkle your nose. Squint your eyes. This is Simon’s basement: long, low and odoriferous.

There are so many words Simon refuses to let me use:

‘S—’ (seven letters, including a ‘q’.)

‘Too scandalous!’

‘P—’ (six letters, oink, oink.)

‘My poor mother!’

‘C—’ (seven, mild, rhymes with butter.)

‘How shaming!’

‘M—’ (six, obscure, but not to Simon; investigated by archaeologists.)

‘Stop writing immediately!’

Simon’s Banned List is a page and a half long. Our most violent argument was over the four-letter ‘f—’ word.

‘No!’ he strangulated.

I am not to use this ‘f—’

‘No!’ he wriggled.

to describe Simon’s fraction of the house under any circumstance. This word ‘f—’

‘No!’ he sank piteously to his knees.

will get him into trouble with the police.

What am I to say?

‘Rooms,’ was Simon’s genteel proffering.

‘No!’ I started from my writing chair. ‘Too polite. I’m not going to lie to my readers to that extent.’

‘You’ve shown no compunction about much greater lies elsewhere.’

‘But,’ I relaunched the argument for ‘f—’, ‘when the house was being assessed for council tax, at one stage the council maintained that it was a separate “f—”.’

‘And it would have meant a lot extra on my council tax bill. Hnnnh, I don’t want to have to go through that again, hnnh.’

‘How about “apar—”?’

‘No! No! No!’

‘Bedsit?’

‘No!’ we shrieked together, and fell about laughing.

Simon has lived in this … this … this … excavation since 1981. Once your eyes have adjusted to the gloom, you’ll see that it’s made up of two rooms: a main one, which extends the full depth of the house, thirty feet from end to end, and the 1970s school-block type of extension at the back that ends with a set of sliding doors opening onto brambles.

Now, slip on your … no, wait. I must say something first about the ‘Titanic Toilet’.

Underneath the booby-trapped stairs we just slid down to get here is a corpse – a dead and rotting lavatory bowl.

Simon was sitting on this toilet when the floor gave way. He and the crapper fell into the abyss so fast that his teeth bit his nose and he would have vanished altogether had the underside of the bowl not banged to a stop against the waste pipe and balanced there, beached, holed, the Titanic of Toilets, teetering over the centre of the earth. Simon hasn’t been able to go near the place since, except to ‘stand’. Wedging his head against the low, sloped ceiling of the stairs, clutching the washbasin with both hands, he teeters his toes to the edge of the broken woodwork – and waters the blackness.

When Simon wants ‘to sit’ he considers even my bathroom upstairs too close to the scene of trauma; he has to go to the farthest possible alternative accommodation in the house: the toilet on the top floor.

Returning to the Excavation. Now is the correct moment to slip on your steel boots, belt up with climbing robes and G-clips, grab a few plasters and a bottle of antiseptic: we’re about to enter the first cave.

It’s easier in here to describe where the paper, plastic bags and books are not than where they are: they’re not on the ceiling.

I suppose you could say, technically, there are no papers on the top third of the walls.

A lot of it trembles in towers on the arms of chairs, on tables, on cupboards, on top of a dinner lady’s trolley that Simon’s managed to wrench out of some local school and rattle back along the midnight streets.

There are outlines of walls, outcrops suggesting a clothes cupboard, a padded chair, one, two, possibly three chests of drawers; no discernible floor; and – watch out! – an I-beam thrusting across the ceiling, indicating that, at some point in this cave’s history, primitive inhabitants have knocked out a wall, possibly during the Cambridge population explosion of the early 1900s.

Finally, here is floor.

We can rest for a moment now and take our bearings. To the right, the front of the house: a bay window, light cut off by blinds (pattern of blinds: coloured, wave-like stripes, perhaps reminding cave inhabitants of the sea). To the left: dinge.

Patterns made in the shadows by the stalagmites of plastic bags and books include a galloping cow, a beetle trying to hide under what was once the padded armchair, the face of a grotesque man …

Gullies moulded into the floor surface of paper-filled supermarket bags, envelopes, squashed boxes, fallen books, mark the route Simon takes when he stomps from his mattress to the toilet under the stairs; the toilet to the kitchen; kitchen (carrying a plate of sardines) back to mattress; then (plate and cutlery bouncing as he leaps up) mattress to front patio door, where the paper disorder gives way and a solitary rut leads through the leaves and fallen shards of masonry big enough to kill, up to the street outside our house – at which point mechanised sweepers and dustbin men take over and the trail disappears.

Amazingly, there are some good pieces of furniture here. Simon’s bed (again, to the right, beside the seascape window blinds) is a nineteenth-century mahogany antique with a Dutch gable headboard and cusped legs. How did this splendid object get in? A gift from ancient gods? It’s placed so Simon MINUS Norton can hear the postman coming up the steps to the front door of the main floor above, leap out of bed, race up the booby-trap stairs and be trembling there with his hands held in a scoop below the letterbox before the first envelope hits the floor.

An eighteenth-century twizzle-legged side table is at the other end of this first room, by the kitchen, washed up on a patch of carpet: the sort of thing found in Cotswold cottages with an arrangement of desiccated flowers sliding off the edge. This table is at an end point of Simon’s stomping route, and bears the brunt of his swinging bag when he turns. Yet somehow a giraffe-shape of paperbacks with alternating dark and light spines has managed to remain in place.

Dr Simon MINUS Norton likes to read books in a single day – packing in pages on train journeys; during delays at bus stops; between bites of sardines in tomato sauce; while floating in the bath – until he has drained the book of information, after which the broken, dog-eared volume is evicted onto a table, under a cushion, inside a saucepan, and begins a descent, measured in a timescale of years, to the archaeological strata on the floor.

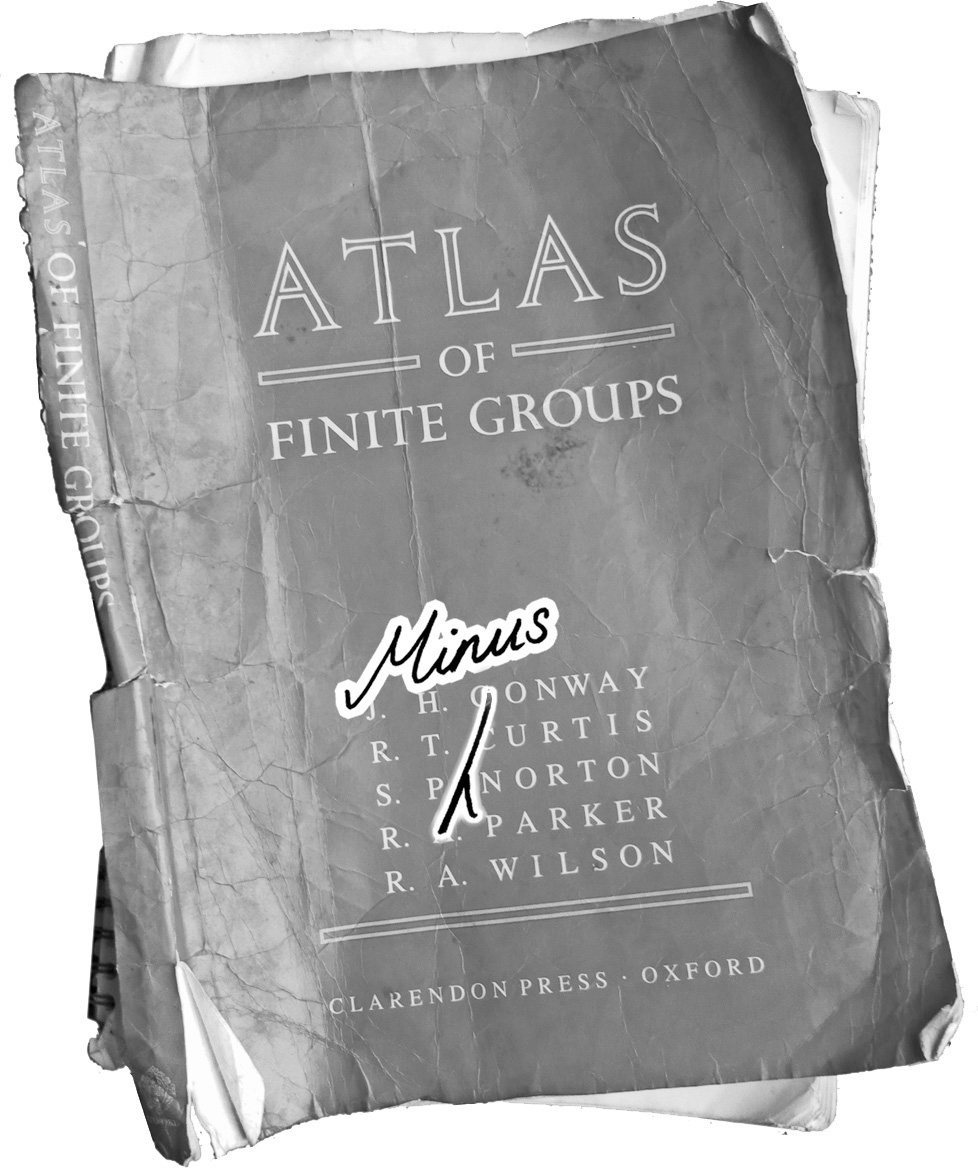

Now that we’re inside this first room or cave, we can take off our climbing gear and start closer investigations. At the bottom of the giraffe pile is a ring-bound book, half an inch thick, pillarbox red, the size of a tea tray: Atlas of Finite Groups, one of the greatest mathematical publications of the second half of the twentieth century. It’s got Simon’s name on it.

Under the bed, if we push aside As the Crow Flies, by Janet Street-Porter, we find a limerick written in a tiny, bumpy hand:

A young girl of Welwyn, named Helen

Was playing near a well, and fell in

She was soaked head to toes

Was (the question arose)

Helen well in the well in Welwyn?

It’s written on exercise stationery, cut with strangling precision around the words and folded so that the creases form a tessellation of diamonds.

Venturing your hand in further under the bed – that’s it, up to the elbow – press your chin hard against that mahogany panel … there! A slipper. Look inside that: another piece of stationery, this time typed, from the Senior Tutor at Trinity College, Cambridge, dated 8 October 1969:

Dear Norton,

The Cambridge Evening News have just been on the line asking whether they could have a few words with you and have a photograph taken. I have told them that you have already been interviewed by the National Press but typically they would want to do it all again …

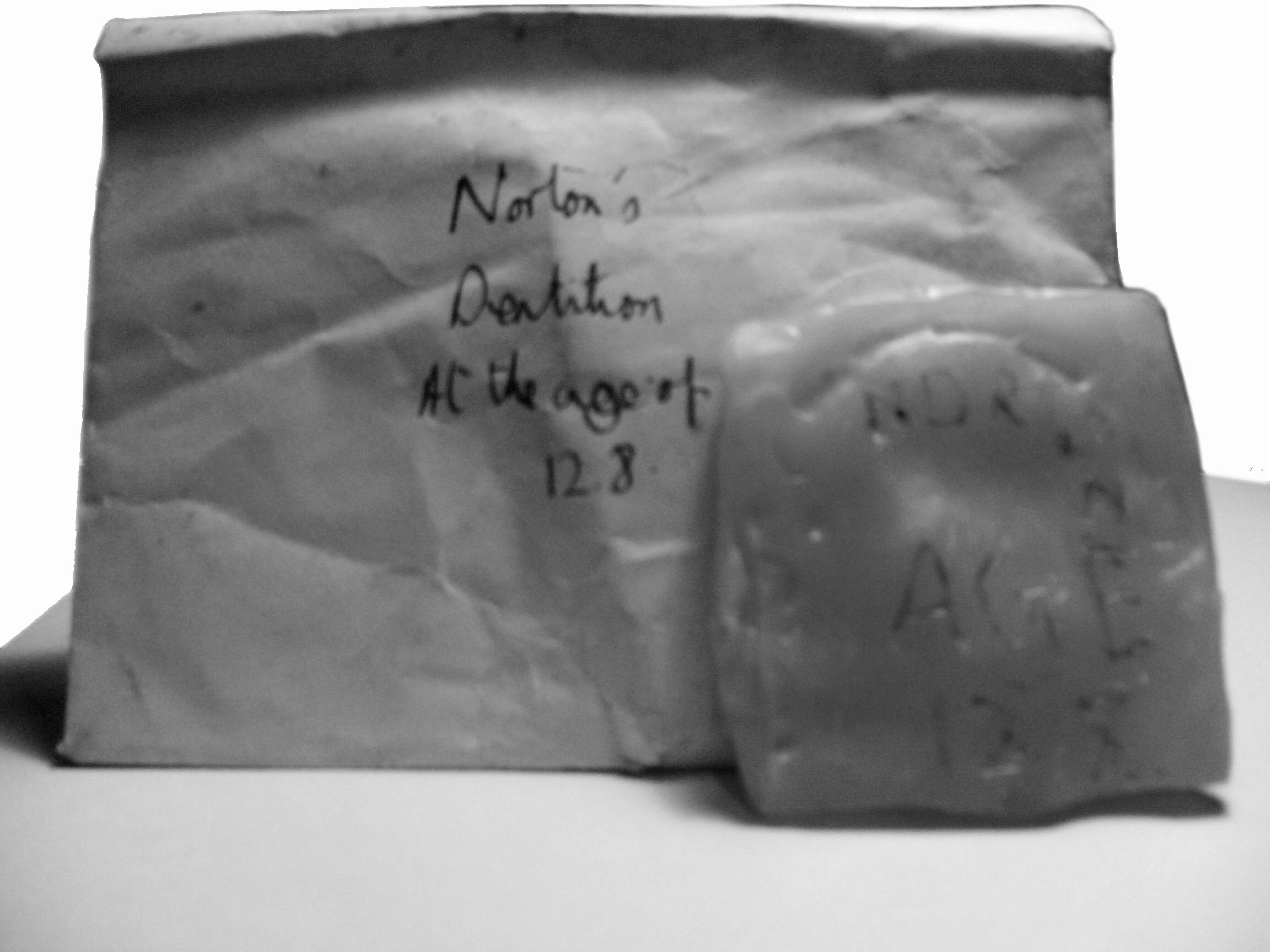

What’s this? The slipper is decorated with a small yellow lozenge at the toe end, showing a smiley cartoon face, the symbol for Ecstasy rave parties in the 1990s. Squashed at the end of the slipper is an envelope, crumpled, containing a thick, pressed chunk, a cake of …

Splendid! A slab of tooth impressions!

Norton’s Dentition At the age of 12.8. Fluorescent pink slab, wax, 3cm x 3cm x 0.5 cm. Excavated and photographed by the author, from a slipper.

Flicking at the plastic bags; clucking to ourselves over the titles of books piled on the armchair; scowling at the three disgraceful jackets coated in mould in the clothes cupboard – we clamber about these rooms feeling annoyance. It’s hard to put a finger on the reason for it.

It’s the vapidity of 99 per cent of this junk. If it was only totally vapid, we could dismiss the man’s life and move on. But over here, if we climb across two cubic cardboard boxes and slide down the other side of a slope of Asda bags next to this chest of drawers containing Simon’s collection of used Tango bottles from the late 1980s, is a second letter. Dated 1971, it’s typed with a heavier hand – a fierce attack on the keyboard. In places the letter ‘o’ has come with the centre shaded and full stops have pierced violently through the paper.

Dear Sir,

As you must be one of the cleverest people alive today, I wonder if you would be interested in assisting me with a project of mine. The idea is to construct an artificial language to exhibit semantic structure in much the same way as a structural chemical formula exhibits the chemical structure of a substance. The project has been examined by Professor Carnap who found it to be ‘ingenious’ …

But then look up: nothing except masses of bags stuffed full of … see! Here, a second letter in a soap-powder box. From the same man, dated eight months later:

Dear Mr Norton,

I am very sorry that you did not reply to my last letter. I suppose I must have offended you that I did not want you to plagiarize my language idea. I should like to make it clear that I did not for a moment think it likely that you would. It was just that I have reached the age of thirty four, and during that time I have been diagnosed as suffering from schizophrenia, a form of insanity …