Полная версия

The Essential Jung: Selected Writings

Then, to my intense confusion, it occurred to me that I was actually two different persons. One of them was the schoolboy who could not grasp algebra and was far from sure of himself; the other was important, a high authority, a man not to be trifled with, as powerful and influential as this manufacturer. This “Other” was an old man who lived in the eighteenth century, wore buckled shoes and a white wig and went driving in a fly with high, concave rear wheels between which the box was suspended on springs and leather straps.

This notion sprang from a curious experience I had had. When we were living in Klein-Hüningen an ancient green carriage from the Black Forest drove past our house one day. It was truly an antique, looking exactly as if it had come straight out of the eighteenth century. When I saw it, I felt with great excitement: “That’s it! Sure enough, that comes from my times.” It was as though I had recognized it because it was the same type as the one I had driven in myself. Then came a curious sentiment écoeurant, as though someone had stolen something from me, or as though I had been cheated – cheated out of my beloved past. The carriage was a relic of those times! I cannot describe what was happening in me or what it was that affected me so strongly: a longing, a nostalgia, or a recognition that kept saying “Yes, that’s how it was! Yes, that’s how it was!”

When Jung began work at the Burghölzli mental hospital, word-association tests were used as a means of studying the way in which mental contents are linked together by similarity, contrast or contiguity in space and time. Jung transformed their use into a tool for investigating emotional preoccupations; and his researches led him to formulate the notion of the “complex,” a term which he introduced.

From “Tavistock Lecture II” CW 18, pars. 97–106

First of all I want to say something about word-association tests. To many of you perhaps these seem old-fashioned, but since they are still being used I have to refer to them. I use this test now not with patients but with criminal cases.

The experiment is made – I am repeating well-known things – with a list of say a hundred words. You instruct the test person to react with the first word that comes into his mind as quickly as possible after having heard and understood the stimulus word. When you have made sure that the test person has understood what you mean you start the experiment. You mark the time of each reaction with a stop-watch. When you have finished the hundred words you do another experiment. You repeat the stimulus words and the test person has to reproduce his former answers. In certain places his memory fails and reproduction becomes uncertain or faulty. These mistakes are important.

Originally the experiment was not meant for its present application at all; it was intended to be used for the study of mental association. That was of course a most Utopian idea. One can study nothing of the sort by such primitive means. But you can study something else when the experiment fails, when people make mistakes. You ask a simple word that a child can answer, and a highly intelligent person cannot reply. Why? That word has hit on what I call a complex, a conglomeration of psychic contents characterized by a peculiar or perhaps painful feeling-tone, something that is usually hidden from sight. It is as though a projectile struck through the thick layer of the persona into the dark layer. For instance, somebody with a money complex will be hit when you say: “To buy,” “to pay,” or “money.” That is a disturbance of reaction.

We have about twelve or more categories of disturbance and I will mention a few of them so that you will get an idea of their practical value. The prolongation of the reaction time is of the greatest practical importance. You decide whether the reaction time is too long by taking the average mean of the reaction times of the test person. Other characteristic disturbances are: reaction with more than one word, against the instructions; mistakes in reproduction of the word; reaction expressed by facial expression, laughing, movement of the hands or feet or body, coughing, stammering, and such things; insufficient reactions like “yes” or “no”; not reacting to the real meaning of the stimulus word; habitual use of the same words; use of foreign languages – of which there is not a great danger in England, though with us it is a great nuisance; defective reproduction, when memory begins to fail in the reproduction experiment; total lack of reaction.

All these reactions are beyond the control of the will. If you submit to the experiment you are done for, and if you do not submit to it you are done for too, because one knows why you are unwilling to do so. If you put it to a criminal he can refuse, and that is fatal because one knows why he refuses. If he gives in he hangs himself. In Zurich I am called in by the Court when they have a difficult case; I am the last straw.

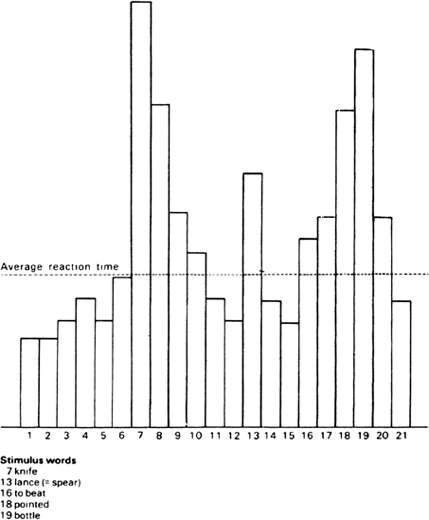

The results of the association test can be illustrated very neatly by a diagram (Figure 5). The height of the columns represents the actual reaction time of the test person. The dotted horizontal line represents the average mean of reaction times. The unshaded columns are those reactions which show no signs of disturbance. The shaded columns show disturbed reactions. In reactions 7, 8, 9, 10, you observe for instance a whole series of disturbances: the stimulus word at 7 was a critical one, and without the test person noticing it at all three subsequent reaction times are overlong on account of the perseveration of the reaction to the stimulus word. The test person was quite unconscious of the fact that he had an emotion. Reaction 13 shows an isolated disturbance, and in 16–20 the result is again a whole series of disturbances. The strongest disturbances are in reactions 18 and 19. In this particular case we have to do with a so-called intensification of sensitiveness through the sensitizing effect of an unconscious emotion: when a critical stimulus word has aroused a perseverating emotional reaction, and when the next critical stimulus word happens to occur within the range of that perseveration, then it is apt to produce a greater effect than it would have been expected to produce if it had occurred in a series of indifferent associations. This is called the sensitizing effect of a perseverating emotion.

Figure 5. Association Test

In dealing with criminal cases we can make use of the sensitizing effect, and then we arrange the critical stimulus words in such a way that they occur more or less within the presumable range of perseveration. This can be done in order to increase the effect of critical stimulus words. With a suspected culprit as a test person, the critical stimulus words are words which have a direct bearing upon the crime.

The test person for Figure 5 was a man about 35, a decent individual, one of my normal test persons. I had of course to experiment with a great number of normal people before I could draw conclusions from pathological material. If you want to know what it was that disturbed this man, you simply have to read the words that caused the disturbances and fit them together. Then you get a nice story. I will tell you exactly what it was.

To begin with, it was the word knife that caused four disturbed reactions. The next disturbance was lance (or spear) and then to beat, then the word pointed and then bottle. That was in a short series of fifty stimulus words, which was enough for me to tell the man point-blank what the matter was. So I said: “I did not know you had had such a disagreeable experience.” He stared at me and said: “I do not know what you are talking about.” I said: “You know you were drunk and had a disagreeable affair with sticking your knife into somebody.” He said: “How do you know?” Then he confessed the whole thing. He came of a respectable family, simple but quite nice people. He had been abroad and one day got into a drunken quarrel, drew a knife and stuck it into somebody, and got a year in prison. That is a great secret which he does not mention because it would cast a shadow on his life. Nobody in his town or surroundings knows anything about it and I am the only one who by chance stumbled upon it. In my seminar in Zurich I also make these experiments. Those who want to confess are of course welcome to. However, I always ask them to bring some material of a person they know and I do not know, and I show them how to read the story of that individual. It is quite interesting work; sometimes one makes remarkable discoveries.

I will give you other instances. Many years ago, when I was quite a young doctor, an old professor of criminology asked me about the experiment and said he did not believe in it. I said: “No, Professor? You can try it whenever you like.” He invited me to his house and I began. After ten words he got tired and said: “What can you make of it? Nothing has come of it.” I told him he could not expect a result with ten or twelve words; he ought to have a hundred and then we could see something. He said: “Can you do something with these words?” I said: “Little enough, but I can tell you something. Quite recently you have had worries about money, you have too little of it. You are afraid of dying of heart disease. You must have studied in France, where you had a love affair, and it has come back to your mind, as often, when one has thoughts of dying, old sweet memories come back from the womb of time.” He said: “How do you know?” Any child could have seen it! He was a man of 72 and he had associated heart with pain – fear that he would die of heart failure. He associated death with to die – a natural reaction – and with money he associated too little, a very usual reaction. Then things became rather startling to me. To pay, after a long reaction time, he said La Semeuse, though our conversation was in German. That is the famous figure on the French coin. Now why on earth should this old man say La Semeuse? When he came to the word kiss there was a long reaction time and there was a light in his eyes and he said: Beautiful. Then of course I had the story. He would never have used French if it had not been associated with a particular feeling, and so we must think why he used it. Had he had losses with the French franc? There was no talk of inflation and devaluation in those days. That could not be the clue. I was in doubt whether it was money or love, but when he came to kiss/beautiful I knew it was love. He was not the kind of man to go to France in later life, but he had been a student in Paris, a lawyer, probably at the Sorbonne. It was relatively simple to stitch together the whole story.

Jung soon began to link the idea of complexes with that of “unconscious personalities.”

From “A Review of the Complex Theory” CW 8, pars. 200–3

So far, I have purposely avoided discussing the nature of complexes, on the tacit assumption that their nature is generally known. The word “complex” in its psychological sense has passed into common speech both in German and in English. Everyone knows nowadays that people “have complexes.” What is not so well known, though far more important theoretically, is that complexes can have us. The existence of complexes throws serious doubt on the naïve assumption of the unity of consciousness, which is equated with “psyche,” and on the supremacy of the will. Every constellation of a complex postulates a disturbed state of consciousness. The unity of consciousness is disrupted and the intentions of the will are impeded or made impossible. Even memory is often noticeably affected, as we have seen. The complex must therefore be a psychic factor which, in terms of energy, possesses a value that sometimes exceeds that of our conscious intentions, otherwise such disruptions of the conscious order would not be possible at all. And in fact, an active complex puts us momentarily under a state of duress, of compulsive thinking and acting, for which under certain conditions the only appropriate term would be the judicial concept of diminished responsibility.

What then, scientifically speaking, is a “feeling toned complex”? It is the image of a certain psychic situation which is strongly accentuated emotionally and is, moreover, incompatible with the habitual attitude of consciousness. This image has a powerful inner coherence, it has its own wholeness and, in addition, a relatively high degree of autonomy, so that it is subject to the control of the conscious mind to only a limited extent, and therefore behaves like an animated foreign body in the sphere of consciousness. The complex can usually be suppressed with an effort of will, but not argued out of existence, and at the first suitable opportunity it reappears in all its original strength. Certain experimental investigations seem to indicate that its intensity or activity curve has a wavelike character, with a “wave-length” of hours, days, or weeks. This very complicated question remains as yet unclarified.

We have to thank the French psychopathologists, Pierre Janet in particular, for our knowledge today of the extreme dissociability of consciousness. Janet and Morton Prince both succeeded in producing four to five splittings of the personality, and it turned out that each fragment of personality had its own peculiar character and its own separate memory. These fragments subsist relatively independently of one another and can take one another’s place at any time, which means that each fragment possesses a high degree of autonomy. My findings in regard to complexes corroborate this somewhat disquieting picture of the possibilities of psychic disintegration, for fundamentally there is no difference in principle between a fragmentary personality and a complex. They have all the essential features in common, until we come to the delicate question of fragmented consciousness. Personality fragments undoubtedly have their own consciousness, but whether such small psychic fragments as complexes are also capable of a consciousness of their own is a still unanswered question. I must confess that this question has often occupied my thoughts, for complexes behave like Descartes’ devils and seem to delight in playing impish tricks. They slip just the wrong word into one’s mouth, they make one forget the name of the person one is about to introduce, they cause a tickle in the throat just when the softest passage is being played on the piano at a concert, they make the tiptoeing latecomer trip over a chair with a resounding crash. They bid us congratulate the mourners at a burial instead of condoling with them, they are the instigators of all those maddening things which F. T. Vischer attributed to the “mischievousness of the object.” They are the actors in our dreams, whom we confront so powerlessly; they are the elfin beings so aptly characterized in Danish folklore by the story of the clergyman who tried to teach the Lord’s prayer to two elves. They took the greatest pains to repeat the words after him correctly, but at the very first sentence they could not avoid saying: “Our Father, who art not in heaven.” As one might expect on theoretical grounds, these impish complexes are unteachable.

I hope that, taking it with a very large grain of salt, no one will mind this metaphorical paraphrase of a scientific problem. But even the soberest formulation of the phenomenology of complexes cannot get round the impressive fact of their autonomy, and the deeper one penetrates into their nature – I might almost say into their biology – the more clearly do they reveal their character as splinter psyches. Dream psychology shows us as plainly as could be wished how complexes appear in personified form when there is no inhibiting consciousness to suppress them, exactly like the hobgoblins of folklore who go crashing round the house at night. We observe the same phenomenon in certain psychoses when the complexes get “loud” and appear as “voices” having a thoroughly personal character.

In 1907, Jung published The Psychology of Dementia Praecox (the current name for what is now called schizophrenia). He sent the book to Freud, and it was this which led to Freud’s invitation to Jung to visit him in Vienna. Jung retained an interest in schizophrenia throughout his life, and wrote a paper on the condition as recently as 1957, only four years before his death.

From “Mental Disease and the Psyche” CW 3, pars. 498–503

In 1907 I came before the scientific public with a book on the psychology of dementia praecox. By and large, I adopted a standpoint affirming the psychogenesis of schizophrenia, and emphasized that the symptoms (delusions and hallucinations) are not just meaningless chance happenings but, as regards their content, are in every respect significant psychic products. This means that schizophrenia has a “psychology,” i.e., a psychic causality and finality, just as normal mental life has, though with this important difference: whereas in the healthy person the ego is the subject of his experience, in the schizophrenic the ego is only one of the experiencing subjects. In other words, in schizophrenia the normal subject has split into a plurality of subjects, or into a plurality of autonomous complexes.

The simplest form of schizophrenia, of the splitting of the personality, is paranoia, the classic persecution-mania of the “persécuteur persécuté.” It consists in a simple doubling of the personality, which in milder cases is still held together by the identity of the two egos. The patient strikes us at first as completely normal; he may hold office, be in a lucrative position, we suspect nothing. We converse normally with him, and at some point we let fall the word “Freemason.” Suddenly the jovial face before us changes, a piercing look full of abysmal mistrust and inhuman fanaticism meets us from his eye. He has become a hunted, dangerous animal, surrounded by invisible enemies: the other ego has risen to the surface.

What has happened? Obviously at some time or other the idea of being a persecuted victim gained the upper hand, became autonomous, and formed a second subject which at times completely replaces the healthy ego. It is characteristic that neither of the two subjects can fully experience the other, although the two personalities are not separated by a belt of unconsciousness as they are in an hysterical dissociation of the personality. They know each other intimately, but they have no valid arguments against one another. The healthy ego cannot counter the affectivity of the other, for at least half its affectivity has gone over into its opposite number. It is, so to speak, paralysed. This is the beginning of that schizophrenic “apathy” which can be observed in paranoid dementia. The patient can assure you with the greatest indifference: “I am the triple owner of the world, the finest Turkey, the Lorelei, Germania and Helvetia of exclusively sweet butter and Naples and I must supply the whole world with macaroni.” All this without a blush, and with no flicker of a smile. Here there are countless subjects and no central ego to experience anything and react emotionally.

Turning back to our case of paranoia, we must ask: Is it psychologically meaningless that the idea of persecution has taken possession of him and usurped a part of his personality? Is it, in other words, simply a product of some chance organic disturbance of the brain? If that were so, the delusion would be “unpsychological”; it would lack psychological causality and finality, and would not be psychogenic. But should it be found that the pathological idea did not appear just by chance, that it appeared at a particular psychological moment, then we would have to speak of psychogenesis, even if we assumed that there had always been a predisposing factor in the brain which was partly responsible for the disease. The psychological moment must certainly be something out of the ordinary; it must have something about it that would adequately explain why it had such a profound and dangerous effect. If someone is frightened by a mouse and then falls ill with schizophrenia, this is obviously not a psychic causation, which is always intricate and subtle. Thus our paranoiac fell ill long before anyone suspected his illness; and secondly, the pathological idea overwhelmed him at a psychological moment. This happened when his congenitally hypersensitive emotional life became warped, and the spiritual form which his emotions needed in order to live finally broke down. It did not break by itself, it was broken by the patient. It came about in the following way.

When still a sensitive youth, but already equipped with a powerful intellect, he developed a passionate love for his sister-in-law, until finally – and not unnaturally – it displeased her husband, his elder brother. His were boyish feelings, woven mostly out of moonshine, seeking the mother, like all psychic impulses that are immature. But these feelings really do need a mother, they need prolonged incubation in order to grow strong and to withstand the unavoidable clash with reality. In themselves there is nothing reprehensible about them, but to the simple, straightforward mind they arouse suspicion. The harsh interpretation which his brother put upon them had a devastating effect, because the patient’s own mind admitted that it was right. His dream was destroyed, but this in itself would not have been harmful had it not also killed his feelings. For his intellect then took over the role of the brother and, with inquisitorial sternness, destroyed every trace of feeling, holdings before him the ideal of cold-blooded heartlessness. A less passionate nature can put up with this for a time, but a highly-strung, sensitive nature in need of affection will be broken. Gradually it seemed to him that he had attained his ideal, when suddenly he discovered that waiters and suchlike people took a curious interest in him, smiling at one another understandingly, and one day he made the startling discovery that they took him for a homosexual. The paranoid idea had now become autonomous. It is easy to see the deeper connection between the pitilessness of his intellect, which cold-bloodedly destroyed every feeling, and his unshakable paranoid conviction. That is psychic causality, psychogenesis.

In some such way – naturally with endless variations – not only does paranoia arise, but also the paranoid form of schizophrenia characterized by delusions and hallucinations, and indeed all other forms of schizophrenia. (I would not class among the group of schizophrenias those schizophrenic syndromes, such as catatonias with a rapidly lethal outcome, which seem from the beginning to have an organic basis.) The microscopic lesions of the brain often found in schizophrenia I would, for the time being, regard as secondary symptoms of degeneration, like the atrophy of the muscles in hysterical paralyses. The psychogenesis of schizophrenia would explain why certain milder cases, which do not get as far as the mental hospital but only appear in the neurologist’s consulting-room, can be cured by psychotherapeutic means. With regard to the possibility of cure, however, one should not be too optimistic. Such cases are rare. The very nature of the disease, involving as it does the disintegration of the personality, rules out the possibility of psychic influence, which is the essential agent in therapy. Schizophrenia shares this peculiarity with obsessional neurosis, its nearest relative in the realm of the neuroses.

From “On the Psychogenesis of Schizophrenia” CW 3, pars. 539–40

Two facts have impressed themselves on me during my career as a psychiatrist and psychotherapist. One is the enormous change that the average mental hospital has undergone in my lifetime. That whole desperate crowd of utterly degenerate catatonics has practically disappeared, simply because they have been given something to do. The other fact that impressed me is the discovery I made when I began my psychotherapeutic practice: I was amazed at the number of schizophrenics whom we almost never see in psychiatric hospitals. These cases are partially camouflaged as obsessional neuroses, compulsions, phobias, and hysterias, and they are very careful never to go near an asylum. These patients insist upon treatment, and I found myself, Bleuler’s loyal disciple, trying my hand on cases we never would have dreamed of touching if we had had them in the clinic, cases unmistakably schizophrenic even before treatment – I felt hopelessly unscientific in treating them at all – and after the treatment I was told that they could never have been schizophrenic in the first place. There are numbers of latent psychoses – and quite a few that are not so latent – which, under favourable conditions, can be subjected to psychological analysis, sometimes with quite decent results. Even if I am not very hopeful about a patient, I try to give him as much psychology as he can stand, because I have seen plenty of cases where the later attacks were less severe, and the prognosis was better, as a result of increased psychological understanding. At least so it seemed to me. You know how difficult it is to judge these things correctly. In such doubtful matters, where you have to work as a pioneer, you must be able to put some trust in your intuition and to follow your feeling even at the risk of going wrong. To make a correct diagnosis, and to nod your head gravely at a bad prognosis, is the less important aspect of the medical art. It can even cripple your enthusiasm, and in psychotherapy enthusiasm is the secret of success.