Полная версия

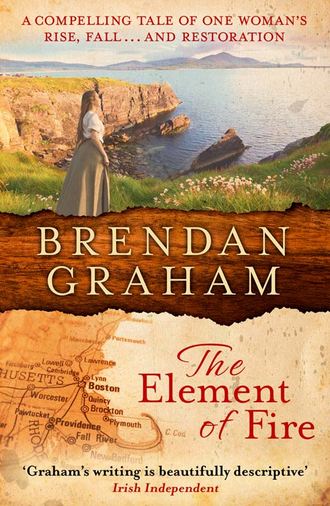

The Element of Fire

It surprised her to hear these talk in their brittle way of ‘the calamity biting deep in Ulster’. She found it hard to reconcile the notion that those who called on the Hand of Providence to strike down the ‘lazy Irish Catholics’, should also be stricken by the same levelling Hand.

‘Planters’, or ‘Scots Irish’, as Lavelle called them; Irish, but not Irish. And they were different. More sober in dress and demeanour than the boisterous middlemen from the southern counties. Two hundred years previously, they had been brought in from the Scottish lowlands, and given Catholic land. In return, they were to ‘reform’ Ireland and the Irish. This zeal had never left them. She had seen them in Boston. Hard work and privilege had kept them where they were – looking down on the ‘other’ Irish, every bit as much as the ‘other’ Irish – her Irish – despised them.

These Scots Irish on board the Jeanie Goodnight already spoke of Boston as if it were theirs, naming out to each other the congregations where they would gather to worship; giving no sense that they were leaving anywhere, only of arriving somewhere else.

Below deck, sober demeanour counted for nothing. Nightly the scratch of fiddles and the thud of reel-sets staccatoed the timbers, as the peasant Irish ceilidhed their way to ‘Amerikay’.

The ‘cleared’, passage-paid by landlords happy to see the back of them, at first rejoiced openly at their leaving. Then, inhabitors of neither shore, they floundered in a mid-ocean of conflicting emotions, fuelled by dangerous grog and the more dangerous fiddle music.

Along with the ‘cleared’ a large body of those below deck were single women from sixteen to thirty years, those Ellen had noticed at the quayside. ‘Erin’s daughters’, fleeing Famine and repression. Most would find their way into the homes of affluent Boston as domestic servants to become ‘Bridgets’. Others would sit behind the wheels of the new-fangled sewing machines in the flourishing clothing and cordwaining shops of the Bay Colony. Others still would become ‘mill girls’, in the Massachusetts mill towns of Lawrence and Lowell. There, their fresh young bodies would make the machines sing and the bosses happy, their spirits thirsting for the fields of home and a cooling valley breeze.

In Boston, the agents of those same factory bosses would be waiting on the piers, to corral the fittest and strongest of these young women, to put shoes on the feet of America, clothes on American backs. She had seen it so many times on the Long Wharf when the ships came in.

And she had seen the jaded ‘Bridgets’ traipse down to Boston Common with their silver-spoon charges, glad of an outing and a few mouthfuls of fresh air. And the threadbare needlewomen, bodies like ‘S’ hooks from fifteen hours a day, every day, shaped over their machines.

America indeed promised much. But it took much in return.

Each evening those below were allowed on deck for an hour to cook what little they had on the open stove before being driven below again. Once uncaged, they tore at their carpetbags like ravenous dogs, until the meagre contents contained within, spilled over the timbers. A few praties, a bag of the hard yellow meal – ‘Peel’s Brimstone’, after the British Prime Minister who sought to feed the starving Irish with it, until it sat like marbles, pyramided in their bellies. Sometimes she saw a side of pig or the hindquarter of an ass, smoked or salted for preservation. Finally, the carpetbags carried a drop of castor oil for the bowels – to clear out Peel’s yellow marbles.

Once, horrified, she watched as a young lad, no older than Patrick, was flung from the carpetbag mêlée by a much older man, his father. The boy careered against the tripod supporting the cooking cauldron. But his screams, as his arms and upper body were scalded, served to distract none but his mother from the frenzy taking place. Ellen ran to summon the ship’s doctor but the boy’s frailty was unable to sustain his sufferings and he expired before relief could be administered.

She noticed, the following evening, that the tragedy stayed no hand from the continuing brawls for carpetbag rations.

Again, Ellen kept the children close to her, having found the silent girl one evening to have disappeared and crept amongst the carpetbaggers, peering into their faces, searching out a spark of recognition between any and herself. Ellen could still get nothing from her, nor did the girl speak to either Mary or Patrick.

At first the strangeness of being on the ship had seemed to frighten the girl – as it did Ellen’s own two children. Then, she became fascinated by it. Looking out on every side, running quickly from windward to leeward, watching the land slide away behind them. Or, facing mizzenward, almost, it seemed to Ellen, listening to the flap of the wind in the masts. Other times she would find the girl staring for hours into the deep, ever-changing waters, finding some kinship there, amidst the white spume, the dark silent depths. What was ever to become of her, Ellen wondered. She would have to give her a name. She couldn’t be just the ‘silent girl’, for ever.

The thirty days at sea, whilst giving Ellen time to regain herself, had done nothing to restore her with regard to Patrick.

He still resented her for deserting them and didn’t seek much to conceal it either. Ellen had decided to let things take their own course between them, not to rush him. But Boston wasn’t far away – and Lavelle. If Patrick didn’t show some sign in the next week or so of coming around, then she would have to sit him down anyway and tell him about Lavelle. Already, when she had returned to Ireland to retrieve the children, her changed appearance and failure to return sooner had caused Patrick to accuse her of having a ‘fancy man’ in America.

6

Three days out of Boston, she spoke to them of Lavelle. ‘I want to tell you about Boston …’ she began. ‘There are a lot of houses. Big, big houses and a lot of streets. Not like our little street in the village, but long, long streets and every one of them crowded with people,’ she explained.

‘Like Westport?’ Mary ventured.

‘Like twenty Westports all pulled together,’ she answered, ‘and the sea on one side of Boston and the rest of America on its other side.’

Mary’s eyes opened wide at the idea. Patrick stayed silent.

‘And Boston Common, itself as big as all Maamtrasna. Where people walk and children play in the Frog Pond and skate in the snow. And,’ she drew in close to them, ‘a giant tree where they used to hang witches! And,’ she moved on, seeing the frightened look on Mary’s face, ‘horses that pull tram carts – you’ll love going in them.’

‘When we get there you’ll be going to school to learn all about Boston and America, and lots of other things besides,’ she went on, wondering what she would do for the silent girl in this regard.

‘Will you not be doing the Lessons with us any more, a –’ Mary started to ask and corrected herself, ‘Mother?’

‘Well, Mary, I think you and Patrick are too grown up for me to be still teaching you at home. The best schools in the whole, wide world are in Boston. It will be very exciting for you both with American children … English and German children … children from everywhere,’ she told them.

‘Will they be like us?’ Patrick spoke for the first time.

Ellen, not sure of what he meant, replied, ‘Yes, of course they will. They’ll all be of an age with yourselves, bright and eager to get on,’ she said, thinking she had answered him.

‘No, but like us – Irish?’ he countered.

She had to think for a minute. ‘Yes, yes, of course there will be children like you, who have come from Ireland. Did I not say that?’

Patrick pressed his point. ‘And what about those?’ he pointed to the deckfloor, ‘those below there?’

‘Well I’m sure they’ll all be wanting education,’ she half-answered. The way Patrick looked at her told her he knew she had tried to skirt his question. She decided to plunge straight on, into the deeper end of things. ‘Now, as well as the schools, you’ll meet some people in Boston … who – who have helped me …’ She slowed, picking out the words. ‘A Mr Peabody, a merchant who owns shops …’

Patrick watched her intently, searching out any flicker or falter that would betray her.

‘Mr Peabody helped me to get started in business and a Mr Lavelle, a friend …’ she could feel Patrick’s eyes burning into her, ‘… who saved my life and helped me escape Australia to get back to you. Mr Lavelle works with me in the business.’

There, she had gotten it all out and in one blurt. It was so silly of her to be nervous of telling them, her own children.

Neither of them had any questions, Mary’s face lighting up at the news that Mr Lavelle had saved her mother’s life.

‘Oh, he must be a good man, this Mr Lavelle, to do that … a good man like Daddy was!’ she added.

‘He is,’ Ellen said, more shaken by the innocence of Mary’s statement than by any hard question Patrick might have asked. It was what she had wanted to avoid at all costs – any notion that Lavelle was stepping into their father’s shoes. He wasn’t. God knows, he wasn’t.

Soon they were within sight of America, evidenced by increased activity in every quarter of the Jeanie Goodnight. Ellen still had not resolved the problem of naming the silent girl. Calling her by no name seemed to be so soulless. How well she had come on since Ellen had first found her. Or rather since the girl had first found them, on the road towards Louisburgh. Now, if only she’d speak – tell them what her name was. Ellen determined to try again with her.

To her horror she found the girl part way up the rigging, seeking a better view of America. Petrified that she’d fall, Ellen anxiously beckoned for her to come down.

The girl jumped on to the deck, smiling at Ellen. Tall and dark-haired, her frame now filled out the skimpy dress that, a month past, had hung so shapelessly on her. Still looked scrawny but at least she was on the way.

‘What’s your name, child, and where did you come from?’ Ellen asked. The girl, eyes still alight with the rigging fun, just looked back at her – happy, forlorn, smiling, such a mixture, Ellen thought. She must have her own pinings and no one to share them with.

The one and only time the girl had spoken, at Katie’s burial, it had been in Irish. She probably had no English. Ellen tried again asking her name, this time in Irish. English or Irish, the silent girl made no response. Ellen was sure the girl heard her, understood her even, but, for whatever reason, could not, or would not, reply.

‘We have to get you a name, child,’ she said, touching the girl’s face. ‘A name to go with those hazel-brown eyes and that pert little nose of yours. A name for America.’

The deck was now getting crowded with sea-weary travellers, jubilant at the sight of land before them. Before she could progress things further with the girl, Mary ran at her all of a tizzy.

‘Is that it, is that Boston?’ she burst out, more like Katie than anything, unable to hold back the excitement the sight before them evoked. Patrick too arrived, his forehead dark and intense with interest, but not wanting them to see it.

Ellen felt her own spirits quicken. Momentarily forgetting her quest for a name, she began pointing out places to them. ‘Look at all the ships! Remember, I told you. And all the islands, let’s see if I still have names for them?’

Mary laughed at the strange-sounding names as Ellen tried to get them right.

‘Noodles Island, Spectacles Island, Apple Island and Pudding Point!’ she rattled off, pleased with herself.

‘No shortage of food here in America then,’ Patrick cut in, trying to deny them the moment.

Ellen ignored him. ‘And that’s Deer Island! We’ll have to stop there for … for the people below, for quarantine … that they have no diseases,’ she hurried to explain.

And their eyes were agape at the size and splendour of America, with its tall spires distantly spiking the heavens.

‘There’s the harbour way ahead,’ she pointed out, trying to distinguish the Long Wharf, ‘where we’ll dock. Beyond that is the State House and Quincy Market.’ They heard the quiver of recognition in her voice as she tumbled out the names, all foreign, all strange to them. ‘Further up is Boston Common – I’ll take you there.’ She hugged the three of them, this time leaving out the witches. ‘On the higher ground at the back – you can’t see it clearly from this far – is Beacon Hill, where once were lit the warning lights for the city if it was going to be attacked.’ She gabbled on, childlike, dispensing all she knew to them. ‘And there’s a place up there called Louisburgh Square – like Louisburgh back home – where we found –’ She stopped, looking at the silent girl in front of her. ‘Louisburgh – that’s it! That’s it!’ She laughed excitedly. ‘We’ll call her after the place where she was found, and the place she is coming to! Louisburgh – we’ll call her “Louisa”.’

Ellen looked from one to the other of them. Mary smiled, nodding her head up and down. Patrick signalled neither assent nor dissent. ‘“Louisa” – it’s a good name, a grand name,’ Ellen went on. How easy it had been in the end – naming the girl. ‘It’ll suit her well! Oh, everything is working out fine! I knew it would once we came to America!’

The silent girl, who had drifted a few paces off from them, sensing the commotion turned from looking at her new home, the place she was now being named for.

‘Louisa!’ Ellen took the girl by the arms, dancing them up and down with delight – like a girl herself. ‘Louisa – welcome to America!’

The girl just looked at her, before turning her attention back to the sight of her adopted home, indifferent in the extreme to her new appellation.

‘It’s not even an Irish name,’ Patrick mumbled, more to himself than anybody.

Ellen, nevertheless, heard him. ‘You’re right, Patrick … it’s not,’ she said sharply, fed up with his surliness.

‘It’s American!’

7

Lavelle was waiting on the Long Wharf for them. As they disembarked he waved, a big smile creasing his weathered face. It was easy to pick him out on the thronged jetty, his well-built frame setting him apart as much as the casual colours he favoured – a russet-coloured jacket; a wheaten homespun shirt – colours of the season. But he wouldn’t have thought of that, she knew, watching the bob of his head – like summer corn in the autumn sun. He never looked Irish, the way Michael did – ‘Black Irish’ with the Spanish blood. Lavelle always looked Australian, reminding her of the bushland, the baked earth, the wide-open spaces. She was pleased to see him, but nervous, none the less, about how the children might regard him. Of her own reaction to him she was clear. He was her business partner, her good companion. She would reinstate that particular relationship from today and that relationship only.

He was restrained when he moved to greet them through the milling crowds, but shook her hand warmly.

‘Ellen, it’s good to see you again! You’re welcome back! And who are these fine young ladies and gentleman?’ he went on, unsure of how to deal with her return.

She saw him stop for a moment as he took in Mary, looked for the missing Katie, then at Louisa, it not making sense to him.

‘This is Patrick,’ she intervened. ‘Patrick, this is Mr Lavelle of whom I spoke … and this is Mary,’ Ellen introduced the nine-year-old image of herself. ‘And this is …’ she paused as Lavelle’s gaze transferred to the silent girl, ‘… this is Louisa, who has come with us to Boston.’ She saw the question still remain in his eyes. ‘We had to leave Katie behind … with Michael.’

He caught her arm, understanding at once. ‘Oh, I’m sorry, Ellen. So sorry – you’ve had so much of trouble … after everything else to …’ he faltered, unable to find the words.

‘Well, we’re here,’ she said simply. ‘At last, we’re here.’

‘And how is it in Ireland?’ Lavelle moved on the conversation.

They would talk later of Katie and this girl Louisa who, when he made to greet her, seemed not to notice. him. She was deficient of hearing, or speech, or both, he thought.

‘Ireland is poorly,’ Ellen answered him, ‘Ireland is lost entirely.’

‘And what of the Insurrection – the Young Irelanders – we read something of it in the Pilot?’ he said, referring to the Archdiocese of Boston’s weekly newspaper.

‘The Insurrection failed – I brought you some newspapers, The Nation,’ she answered. ‘There was much talk of it in Ireland and aboard ship. I have little interest in it. Now we are here and Ireland is …’ she turned her head seawards, ‘… there.’

He heard the weariness in her voice. God only knows what she had gone through to redeem her two remaining children.

‘Mr Peabody enquires after you frequently,’ he said, in an effort to brighten her up, knowing how much she enjoyed her dealings with the Jewish merchant.

‘Oh! And is he well himself, and the business – how is it?’ she asked.

‘Both Mr Peabody and the business continue to thrive,’ he told her with a certain amount of satisfaction, she noticed. Things must have gone better between him and Peabody, in her absence, than she had hoped for.

The children were agog at Boston’s Long Wharf, stretching, as Mary put it, ‘from the middle of the sea, to the middle of the town’.

‘City,’ corrected Patrick, showing he was a man of the world, not like his sister who knew nothing. ‘It’s a city!’

If Westport Quay swirled with all the varied elements of quayside life, then here, in Boston, it was as if the mixed ingredients of the whole world had collided together. Tea-ships, ice-ships, spice-ships. Syphilitic sailors, back from the South Seas, poxed and partially blind, bringing home with them ‘the ladies’ fever’ and the stale stench of flensed whales. In their midst stood sinless and sober-suited Bostonians cut from the finest old Puritan stock; anxious for merchandise, disgusted by this new influx of paupers and the sanitary evils accompanying them.

The hiring agents of the mill bosses sized up this fresh supply of factory fodder. ‘Labour!’ they hollered, to the sea of ‘green hands’. ‘Labour!’ they called, winking and smiling at the wide-eyed Irish girls. Seeking to seduce with smiles, as much as with dollars, those they considered ‘sober of habit, sound of limb and with good strong backs’ – as they had been instructed. One man’s ‘sanitary evil’, it seemed in America, was another’s ‘strong back’.

The children’s heads turned at every step, gawking at this and that, each new sight and sound of Boston a greater wonder to them than the one before. Like the gaudily bedecked sailors of various hue, reeking of spices and perfumes from the far reaches of the Orient, chattering in unintelligible tongues. Or a few freed slaves from the South silently bullocking the heavy cargo. She had to prevent them from staring.

‘But that man … he’s all black, what happened to him?’ Mary couldn’t contain herself.

‘He’s a Negro – from Africa,’ Ellen hushed her.

‘But will it rub off?’ Mary persisted.

‘Only if you shake hands with him, Mary,’ Lavelle cut in solemnly.

Mary’s eyes opened even wider, craning her neck to see this man who would change colour at a touch.

‘Mr Lavelle should have more sense, Mary, ignore him!’ Ellen rejoined. ‘Some people have a different skin to ours, that’s all – and it doesn’t rub off!’ she stated emphatically, more to Lavelle than to Mary. Nothing she had told them about America had ever prepared them for this, for Boston’s Long Wharf.

And the Irish. Everywhere the Irish; shouting, laughing, crying, mobbed by relatives who had crossed the Atlantic before them. Others, solitary young girls clinging to their carpetbags – no one to meet them in this throbbing kaleidoscope, this frightening place. Like motherless calf-whales they were, these daughters of Erin floundering unprotected in the great ocean of America. Easy prey to the welcoming smile, the outstretched hand, the familiar lilt; to their own, the Irish crimpers and ‘harpies’, who would flense them of everything.

‘I can see that Boston is as busy and bustling as ever,’ she said to Lavelle, full of being back in the place.

‘And bursting at the seams – thousands have arrived these past months – mostly Irish,’ he replied. ‘The bosses are happy; “green hands” from Ireland mean cheap labour,’ he continued, ‘but the City Fathers are not, thinking pauperism and Popery both will sink Boston!’

She didn’t care much about either bosses or Brahmins. Boston, bursting or not, was such a far cry from what she had left; the tumbled villages, a famished land; silence – no hope. Here there was hope. To her, the city with its crowded chaos, its cacophonous quay-life, rang out with the very music of hope.

‘Stop, Lavelle! Stop here!’ she called out of a sudden, almost forgetting. ‘I want them to see it!’

Lavelle ‘whoaupped’ the big bay mare he had hired for the day and had scarcely pulled them to a halt, when gathering up her skirts she leapt from the trap-cart.

‘Come on, come on!’ she beckoned to the children, shepherding them across the mouth of the busy wharf.

Lavelle stayed where he was. She was as impetuous as ever, he thought, watching the long straight back of her weave through the crowds. He smiled to himself – the factory bosses would be glad of a back like that! Three months since she had left and he had thought about her every day, wondering what awaited her in Ireland. Wondering when, if ever, she would return. Then, these past few weeks, scouring the pages of the Pilot for shipping intelligence and hoping for a fair wind to bring her back.

She looked a bit racked, he thought. Her face, the way she didn’t smile as big as he remembered. The furrow above her lips – the one he could never help watching, fascinated at how its fine fold rose and fell with the cadence of her speech. It didn’t fall and rise so much now, as if she was holding it back, keeping it in check. Still, it was a wonder at all that she looked as well as she did. She must have been too late to save them both, whatever had happened. That must have near killed her, would eat away at her for ever, he knew. This one, Mary, with the dos of wild red hair on her – how like Ellen she looked. Going to be tall like her too. He could see it now, as together they rounded the corner of the building away from him. The girl was quieter, less impetuous, more of a thinker. But maybe that was down to the foreignness of the place and him being present. And all that had happened.

The boy had made strange with him. With his unruly black head and sallow skin, he looked more like he’d come off a ship from the Spanish Americas, than Ireland. He was unlike her in every feature. Lavelle wondered about the boy’s father, her husband. It was her strong attachment to his memory that was holding back her affections. He had been hoping that when she stepped down from the ship, she would be wearing the scarf he had given her. But she wasn’t. He wondered what she had told the children. Or, if she’d thought much on him at all these past three months?

And the girl – the one who said nothing, only taking you in with those big brown eyes. Where had she appeared from? Maybe she was a neighbour’s child, orphaned by famine. Nearly more orphanages than groggeries in Boston too, so fast were they springing up. She’d probably put the girl into one of those – run by the Sisters. He ‘gee’d’ the horse, threading it gingerly after them, glad that he’d painted the sign. It would be a surprise for her. She was standing in front of it, her finger outstretched, reading aloud the strange-sounding words to the children. She turned, hearing the clip-clop of the horse.

‘Mr Lavelle’s been busy painting, I can see,’ she said to them. But it was meant for him, he knew. ‘“The New England Wine Company”,’ she read out the larger letters again, then the smaller ones underneath, ‘“Importers of fine wines, ports and liqueurs”. That’s us!’ she said to them with a little laugh. Even Patrick seemed impressed, looking at her, then at the sign over the warehouse, then back at Lavelle, trying to piece it all together.