Полная версия

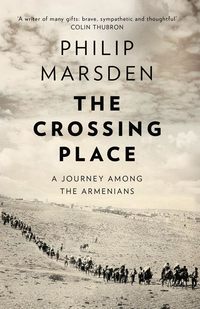

The Crossing Place: A Journey among the Armenians

PHILIP MARSDEN

The Crossing Place

A Journey among the Armenians

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2015

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers in 1993

Copyright © Philip Marsden 1993

Preface and postscript copyright © Philip Marsden 2015

Philip Marsden asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

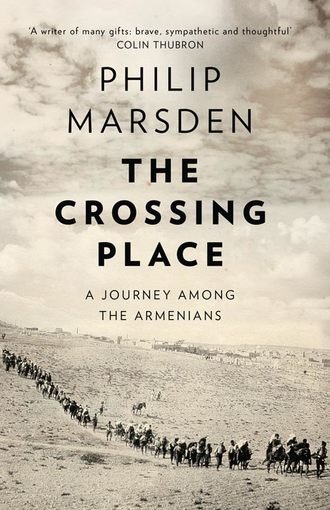

Cover photograph: Turkey / Armenia: Armenian refugees fleeing

Turkish massacres, Anatolia, 1915 © Bridgeman Art Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008127435

Ebook Edition © April 2015 ISBN: 9780007397778

Version: 2015-03-17

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

EPIGRAPH

The wind is singing, the leaves of the mulberry-tree are shuffling.

Eternal song; eternal life; eternal death; eternal sorrow; and eternal joy…

Vahan Totovents, Scenes from an Armenian Childhood,

(Trans. Mischa Kudian)

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Epigraph

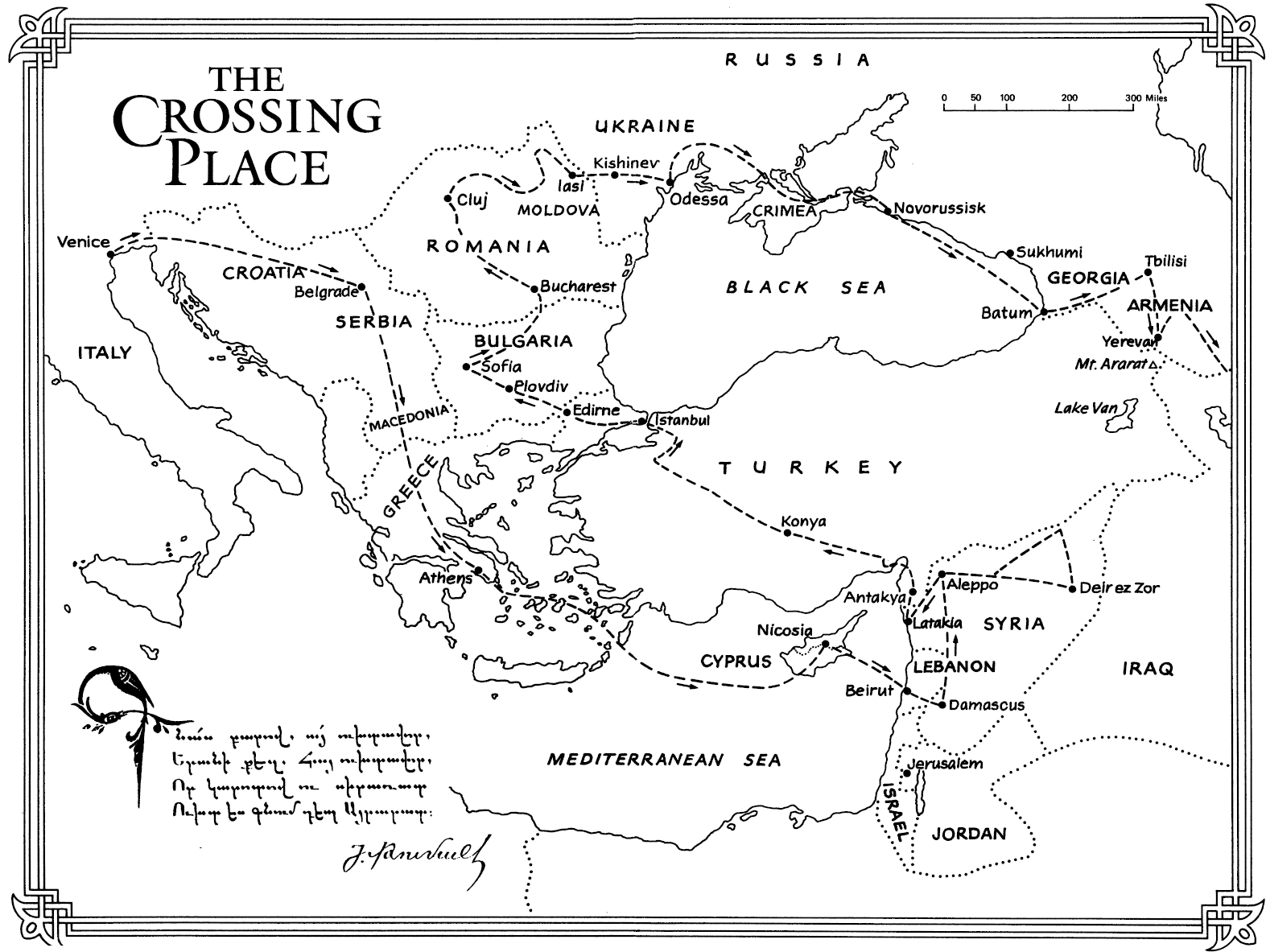

Map

Preface to the 2015 Edition

Prelude

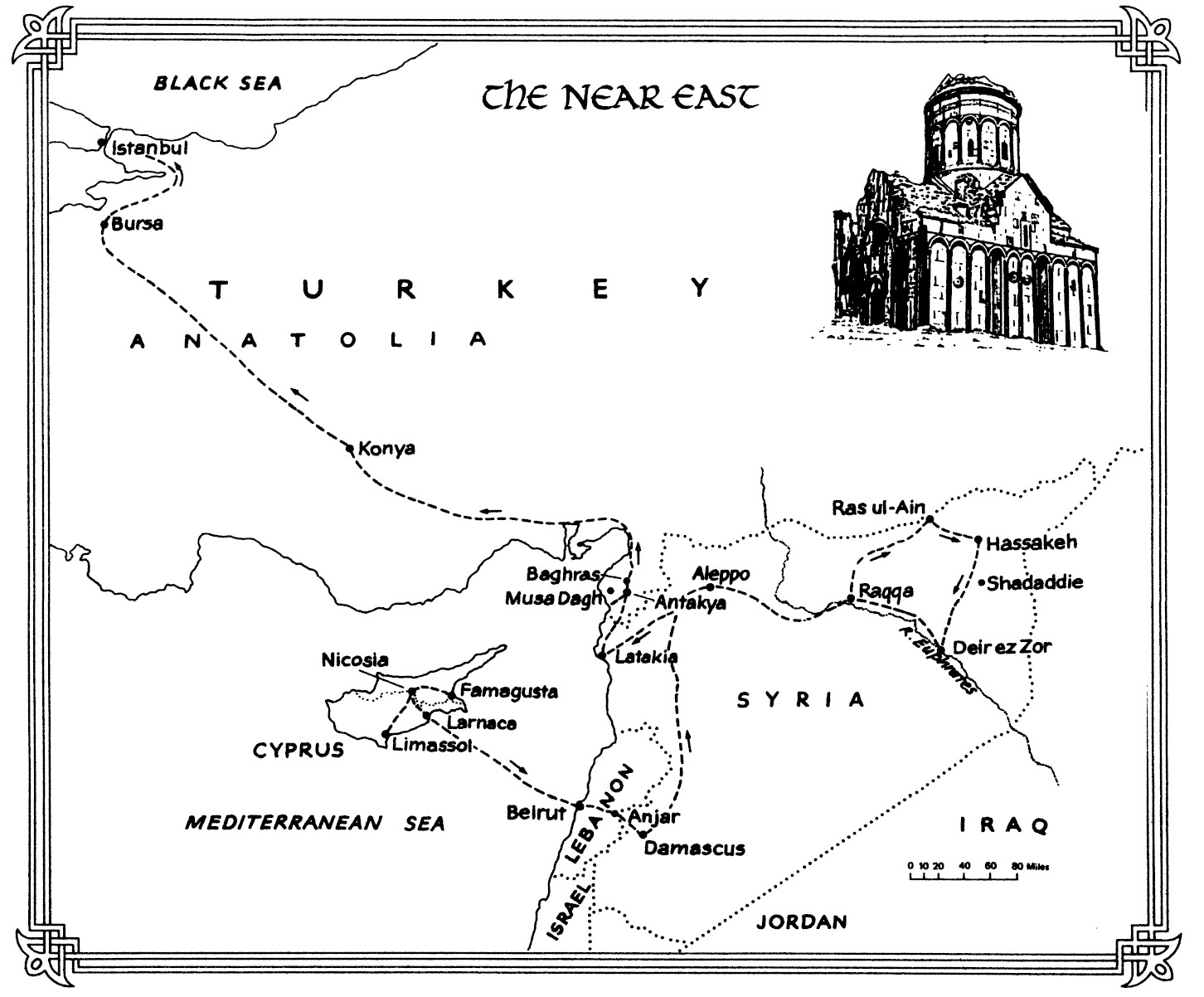

Part I The Near East

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

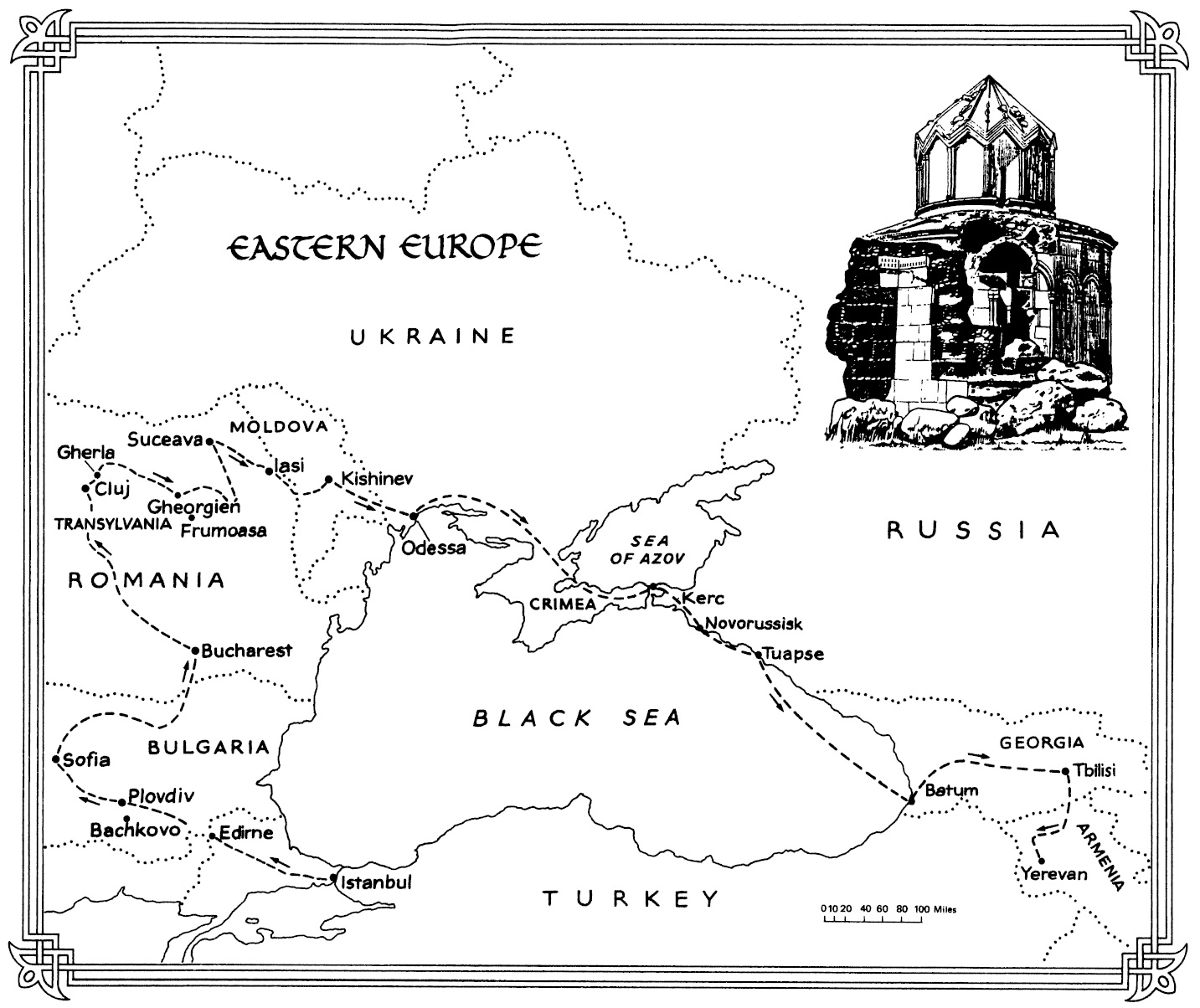

Part II Eastern Europe

9

10

11

12

13

14

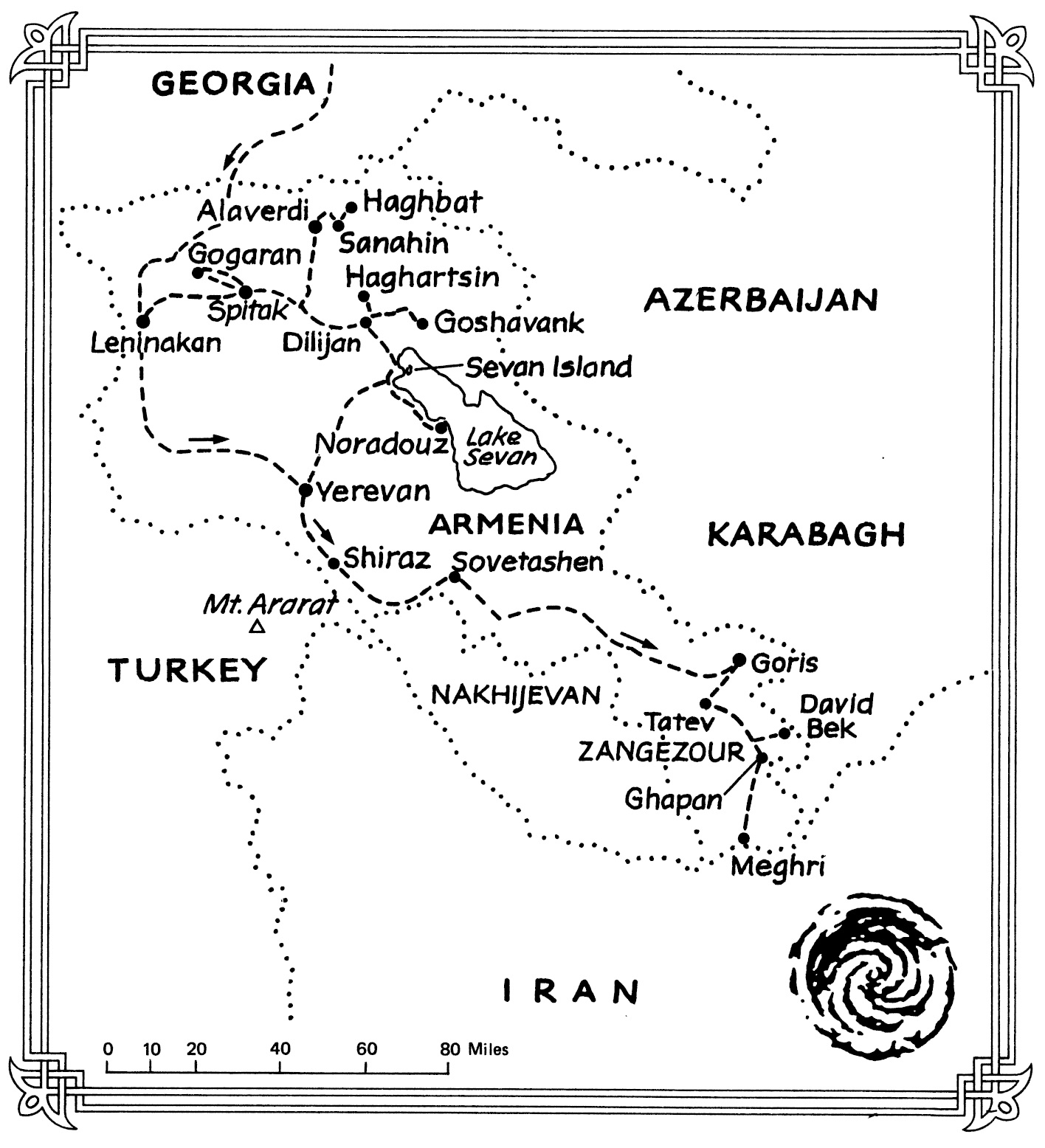

Part III Armenia

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Postscript

Keep Reading

References

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

MAP

PREFACE TO 2015 EDITION

On a cold grey morning in January 1991 I stood beneath the departures board at London’s Victoria Station, waiting to catch the boat-train to Paris. A rucksack leaned against my shins and a crowd of commuters – blank-faced and winter-wrapped – flowed past me. I was in my late twenties, and I was going to Armenia.

In my pocket I had a black oilskin notebook with a list of Armenian sites and contacts in places from Venice to Nicosia, Damascus to Sofia, Aleppo to Cluj, Istanbul to Bucharest. I had arranged them by country, and the last page was headed USSR – still in existence, just, with names in Odessa, Tbilisi and Yerevan. I was wearing new boots and a new coat. In my rucksack was a change of clothes, a towel, books, two maps (one ‘Turkey and Western Asia’, the other ‘Osteuropa’), a short-wave radio, a Nikon F3 camera, a lot of transparency film, a letter of introduction from the Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem and $2,000 in cash. I also had two passports, one with Israeli stamps and one without. In neither of the passports was a single visa.

I felt neither prepared nor unprepared; the uncertainty of the journey was too great to be nervous. I had developed an idea of the traditional Armenian diaspora as a powerful and secretive network of communities spread across the Middle East and Eastern Europe. If I locked into that network, and was accepted, all would be fine. Visas would appear, borders would open before me. At least that was what I hoped: proving it was part of the point of the journey. My two main fears were being kidnapped in the Levant and being turned back, anywhere. I was determined not to fly.

From Paris my plan was to carry on by train to Venice, then to Athens, and by ferry to Cyprus. That was the easy part. From then on, I would need visas and luck and the help of my contacts. The first decision would be whether or not to go to Lebanon. The bombing phase of the First Gulf War was already underway; Western hostages were still being held in Beirut and the Bekaa Valley.

For months before, I’d been living in a single-room flat in the Armenian quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City. I took daily lessons in Armenian with the charming Father Anooshavan, who was alleged to speak thirty-six languages. I spent a great deal of time with the poet and historian George Hintlian, who acted as mentor to my planned odyssey. I talked to monks, scholars and seminarians. I met recent refugees from Karabagh, second-generation refugees from Iran, and third-generation refugees from Turkey. In 1915 the entire Armenian population had been driven from Anatolia; many were massacred there, on the edge of dusty towns; many more were driven down into the Syrian desert. Over a million died. In Jerusalem, there were a few very old survivors who, in darkened rooms, laid their stories before me.

At that time the Old City was more than usually tense. On to the first Palestinian Intifada were heaped the war-fears that had followed Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait. I recall the cheek-sting of tear gas, the fear of walking in the alleys at night, of a stone to the head or a street stabbing. I recall the Al-Aqsa massacre of 8 October and watching an Israeli settler standing in the Ghawanima minaret, shooting down at Palestinians in the concourse of the mosque.

That morning at Victoria station, I carried a couple of other things with me, things I’d picked up in Jerusalem. One was a particular strain of anger that is unavoidable if you spend any time in the Middle East. I had arrived in Jerusalem with an outsider’s view of the Palestinian conflict. But as the months passed and I saw the reality of day-today life, I found myself with a visceral reaction to the Israeli occupation. A similar indignation, overlaying any attempt at neutrality, had grown to colour my Armenian studies. In 1915, under threat from enemies on all sides, the Turkish authorities had every right to be nervous of Armenian loyalties. But what they did to the Armenians overshadows any political context. This book is not an attempt to explain the events of 1915; it is the record of my own experience of travelling among the Armenians, at a particular moment in world history, at a particular moment in my own life. Re-reading it now, more than two decades on, I can see how partisan I’d become, and remember how natural that position felt.

The other piece of baggage was something that would grow sharper over the coming months, that would stay with me for years afterwards. It was the idea that violence and disorder were the way of the world, and that at that time in the early 1990s, with the Middle East in chaos and the Soviet Union fracturing, they were both on the rise. I was, I recall now, in that state of mind that sees everywhere the signs of imminent catastrophe.

Two months later I reached the Syrian town of Deir ez Zor. After days in the desert, visiting the massacre sites, I crossed the Euphrates on a bus. It was late afternoon and a dusty light hung heavy over the town, as if the sun had lost its vigour. Down a side alley, I knocked on a door and an Armenian let me in swiftly and locked it behind him.

I don’t remember much of that evening, except his ninety-year old mother sitting still and silent on a stool. But in the morning he took me to see something remarkable. Amidst the boxy concrete buildings, the overhead tangle of wires, stood the Armenian Martyrs’ Memorial church – only just completed.

It wasn’t only a church but an entire complex of buildings – a museum, an archive, community rooms. The sunlight glowed on walls of fresh-cut, butter-yellow limestone. Into the stone were carved khachkars, those crazily intricate Armenian crosses that mark places of note. Down in the crypt of the church was a gallery of black-and-white photos of the massacres – beheaded men and naked starving women and, like members of a lost family, the Anatolian towns from which the Armenians had been driven. Full-length silk robes and silverware stood in glass cases. It was all that was left.

In the middle of the room were more glass cases, but these ones were set into the floor. Under the glass lay the pale bones of victims. Some of them had come from the cave at Shadaddie, where several thousand people had been burnt and suffocated. From the middle of the ring, rising from the bones like a tree trunk, was a marble pillar. Its stocky girth pushed up out of the crypt, through a hole in the floor above and into the main space of the church. I leaned in to gaze at its light-tinted top, probing the interior as if it was another world. It was named the Column of Resurrection.

The church was consecrated just a couple of months after I visited. The Armenian Catholicos of Cilicia came up from Beirut to conduct the ceremony. Over the years since, tens of thousands of Armenians have made the journey across the desert to visit the Martyrs’ Memorial church. Until the recent Syrian civil war, a vast gathering took place there each year on the day of commemoration, 24 April. The memorial site is often compared to Auschwitz, built at one of the places where the Armenians were concentrated after their long march, and where they died in such numbers. It is a site that for Armenians offers a hint of solidity amidst the perennial loss – stone buildings to offset the villages and towns that were gone, the centuries-old way of life, the abandoned cemeteries and ancient khachkars, the generations that might have been born.

In the summer of 2014, the town of Deir ez Zor fell into the hands of ISIS. The Armenian priest received a phone call inviting him to accept their authority. He refused. The Armenian Church of the Holy Martyrs was dynamited. Its treasures and mementoes were destroyed, its archive burnt. The charred bones from Shadaddie were buried once again, in tons and tons of rubble.

The story of the Armenian massacres did not begin in 1915, and nor did it end then. Persecutions stretched back through the centuries, flaring into periodic pogroms and forced exile. The Armenian communities set up elsewhere have proved often just as frail, just as vulnerable. When I was in Aleppo in 1991, refugees from the civil war in Beirut had pushed the Armenian population in the city to one hundred thousand; from 2012, the tide turned and the Armenians fled the opposite way.

The collective memory of 1915 has followed its own precarious and unpredictable path. For decades, the Armenians were almost silent, as if a combination of shock and shame prevented them saying anything. Then on the fiftieth anniversary, in 1965, one hundred thousand people gathered in Yerevan to demand restitution of historical lands in Turkey. The effect was extraordinary. Many in the Soviet republic didn’t even know of the catastrophe, while in the diaspora the scattered victims and their descendants suddenly found a voice. Thereafter, the cries for recognition grew louder and the sense of grievance became a powerful political force.

The reaction of the Turkish state has been denial – denial that there was ever a systematic campaign to rid the country of Armenians, denial that Armenian deaths were anything more than incidental damage caused by civil conflict. Armenian anger intensified. In the 1970s, extremists conducted a campaign of terror against Turkish diplomats. Many more have been involved in more restrained lobbying of governments around the world to recognise the genocide – which in turn has provoked further dismissal from the Turkish state.

No-one now has any direct memory of what happened in 1915. The survivors I interviewed are long since dead. Although the dissemination of evidence has grown in the intervening years, the entire episode has been successfully muddied by Turkish denial. The debate has revolved around whether or not there was a ‘genocide’, a concerted attempt to eradicate the Armenians as an ethnic group and whether it is possible to describe it with a word that was only coined in 1948. The polarisation of opinion, the fear of Turkish retribution against parliaments who vote to acknowledge the Armenian genocide, have helped to maintain the opacity of the water.

The terminology doesn’t matter. The events remain, casting their shadow over the entire twentieth century. In 2009, Geoffrey Robertson QC trawled the available material and wrote a report entitled ‘Was there an Armenian Genocide?’ ‘No reputable historian,’ he concluded, ‘could possibly deny the central facts of the deportations and the racial and religious motivations behind the deaths of a significant proportion of the Armenian people.’

I am often asked: what interested you in the Armenians? I used to find the question surprising: who could not be interested in the Armenians once you knew their story? But I now realise that what people really meant was this: why did I immerse myself so completely, cut myself off so entirely, in order to travel through the diaspora and down to the southern Caucasus?

That year was the most extraordinary of my life, yet I still find the question hard to answer. I was motivated by the genocide, yes, the shock of discovering its details and the continuing campaign of denial. But it wasn’t just that, nor even mainly that. Nor was it the extraordinary achievements of the Armenians – the perfect stone churches, those miracles of form in the treeless expanse of eastern Turkey, nor the devotional beauty of the medieval manuscripts. It wasn’t the music, the repertoire of traditional laments and marriage songs, the strains of the kamancha or the duduk, which in a few breathy notes can conjure up a yearning for Armenia and its mountains even for those who’ve never even seen them.

All those things are astonishing but they were not what kept my curiosity alive. It was something about the Armenians themselves, their half-hidden role in history, their Zelig-like presence in the Byzantine Empire, the Mughal Empire, the Ottoman Empire, the Soviet Empire. It was what they knew of the world, of the deep lessons of loss and landlessness, of living among strangers, of how to make light of borders and the obstacles of long journeys. It was the nobility of so many of their lives, the fierce conviction that our mortal endeavours should be pursued always with energy and courage, that to be alive is to be awake, never to be complacent, never to rest, that any sense of belonging on this earth is both fleeting and illusory. Sometimes it seems to me as if long ago, far back in a collective past that pre-dates most of the world’s existing ethnic groups, the Armenians discovered a secret, and swore never to disclose it but hand it down from generation to generation, wherever they happened to be. It’s a secret that’s been so closely guarded for so many centuries, that what remains is less the secret itself than the habit of keeping it.

That would explain their survival, the ceaseless exercise in will and competence that sustains it. It would explain the life of individuals like Joseph Emin, whose roamings took him from the courts of eighteenth-century Europe to the Caucasus to try and liberate his people. It explains too the fedayi I saw that first day in Yerevan, down from the mountains to bury their dead with their black beards and blue-grey eyes, and Janna Galstian, who abandoned a brilliant acting career for war in Karabagh where I met her in 1993 as deputy military commander of the Hadrout region. It explains the life and work of the great musician Gomidas, collector of a thousand Armenian folk songs, who deciphered the medieval notation system but was driven out of his mind by the experience of 1915. It explains the power of the letters of Mesrop Mashtots’s Armenian alphabet and the melismatic chants of the church choirs, and the genius of Armenian masons, photographers and merchants, and of those Armenian priests, stuck in some far-off outpost of the diaspora, in Poland or Transylvania or Iraq who say the liturgy for the last time to an empty church, then lock the door and step outside, into the dangerous world.

Philip Marsden, Ardevora, December 2014

PRELUDE

One summer, walking in the hills of eastern Turkey, I came across a short piece of bone. It was lodged in the rubble of a landslip and had clearly been there for many years. I rubbed its chalky surface and examined the worn bulbs of the joint; I took it to be the limb of some domestic animal and dropped it into my pocket.

Beyond the rubble, the land fell away to a dusty valley which coursed down to the plain of Kharput. The plain was hazy and I could just make out a truck bowling across it, kicking up a screen of pale dust in its wake. I carried on down the valley. It was a strange, still place and rounding a bluff, I stumbled on the ruins of a village. A shepherd was squatting in the shade of a tumbled-down wall, whistling. I showed him the piece of bone and gestured at the ruins around him.

The shepherd nodded, wiping together his palms in an unambiguous gesture. He said simply, ‘Ermeni.’ Then he took the bone and threw it to his dog.

Ermeni: the Armenians. The guide books hardly mentioned the Armenians. No one mentioned the Armenians, yet everywhere I went over the coming weeks, every valley of that treeless Anatolian plateau, was haunted by them. Arriving one morning on the shores of Lake Van, I took a boat to the island of Aghtamar. The island had once been the court of an Armenian king, the centre of a tiny realm squeezed between Persia and Byzantium, but now it was uninhabited.

Continuing north, around the lower slopes of Mount Ararat, I came to the ruins of the Armenian city of Ani. Its extraordinary thousand-year-old cathedral, in no man’s land between the Turkish and Soviet borders, was open to the sky, shelter for three ill-looking sheep. A long way up a gorge near Digor, I found an Armenian church so perfect in its design that at first I did not notice its collapsing roof, nor the gaps in its walls.

I left Anatolia with a clutch of half-answered questions. Who were these people, and what had happened? I knew about as much as most – that the Turks had done something terrible in the First World War, that Armenia was the first Christian nation, that it had hovered for centuries on the fringes of the classical world. But it was not an explanation. Everything that I learnt about the Armenians only served to deepen the mystery, to make them more surprising, more enigmatic.

The following year I was travelling through northern Syria and came across an archaeologist in Aleppo. He knew a good deal about the Armenians and one afternoon took me to meet Torkom, an elderly Armenian lawyer with a bony face and deep-set blue eyes. Torkom lived alone, at the top of a set of winding stairs. His room was dark and musty and filled with books. A few glass-fronted cases had been built into the wall for manuscripts and they glowed with a yellowy light; they looked like preserved organs in laboratory jars.

When he heard I was interested in the Armenians, Torkom peered at me suspiciously.

‘Why?’

I said I’d been to eastern Anatolia.

‘Yes?’ I told him about the cathedral at Ani and the church at Digor. I told him about the bone and the ruined villages and he shrugged as if to say: ‘What do you expect?’

But when I mentioned Lake Van, he said, ‘My family was from Van. You see my eyes? I have Van eyes – deep blue.’

‘Like the lake,’ I said. He smiled and led me into a back room. A photograph of Mount Ararat hung on one wall. Beneath it was a large desk, covered in papers.

‘Do you know anything about the marches?’ he asked.

‘Very little.’

He opened one of the drawers and handed me the xerox copy of a hand-drawn map. Years of interviews had gone into that map, he said. He had collaborated with an Armenian truck driver who knew every town and village of northern Syria, and they had spliced the oral information with the few written records to draw the map. It looked to me somewhat like a tidal chart: a mass of arrows curling and twisting down the page. But the arrows, when I looked closely, were overlaid on a map of the Near East and they all pointed in more or less the same direction, away from Anatolia, south towards the Syrian desert.

I spent the following day in Torkom’s library.

On 24 April 1915 the Turkish authorities arrested Constantinople’s six hundred leading Armenians. They rounded up another five thousand from the city’s Armenian quarters. Few of these people were ever seen again.

In the interior Turkish forces began to deport the Armenians. Torkom showed me the published report of one of the only foreigners who had witnessed what these deportations really meant. Leslie Davis had been the American consul in Kharput. He had watched the Armenian groups come and go, and had listened to the rumours. Since it was wartime his movements were severely restricted and he had been unable to confirm what he heard. But one morning before dawn he managed to slip out of the town. He rode on to the plain of Kharput.

And wherever he rode he saw the Armenians. They were casually buried in the roadside ditches, their limbs half eaten by scavenging dogs; he saw the heaps of charred bones where the remains had been burned; he saw the swollen bodies of the newly dead and in places they lay so thickly in the dirt that his horse had difficulty avoiding them. As the day wore on, Davis rode further into the hills. He reached the shores of Lake Goeljuk. Here, in the valleys leading down to the lake, the scene was the same: corpses scattered amidst the thornscrub, bunched together in their hundreds – at the foot of cliffs, in gorges, in the hidden folds of land.

Those who weren’t killed at once were gathered into convoys and driven south. These were the marches. Davis had managed to compile an account of just one of these dismal convoys; it had left Kharput on 1 July 1915:

Day 1 3000 Armenians leave Kharput. Escort of seventy zaptieh under command of Faiki Bey. Day 2 Faiki Bey levies 400 lira from convoy for its safety. Faiki Bey disappears. Day 3 First women and girls taken by Kurds. Open violation by zaptieh. Day 9 All horses sent back to Kharput. Day 13 200 lira levied by zaptieh. Zaptieh disappear. Day 15 Kurdish ‘guard’ take 150 men and butcher them, then rob convoy. Joined by another convoy from Sivas. Numbers swell to 18000. Days 25–34 Harassed by villagers. Many women taken. Day 40 Eastern Euphrates. Blood-stained clothes on river-bank; 200 bodies in water. Armenians forced to pay to avoid being thrown in river. Day 52 Kurds take everything, including clothes. Day 52–9 Naked, without food or water. Women bent double from shame. Hundreds die beneath hot sun. Forced to pay for water. Money hidden in hair, mouth, genitals. Many throw themselves into the wells. Arab villagers give them pieces of cloth out of pity. Day 60 300 remain from 18000. Day 64 Men and the sick burned to death. Day 70 150 arrive in Aleppo.When I rose after several hours of reading such accounts, I felt dazed and numb. I walked back into the centre of Aleppo, through the high, narrow streets with their 1950s cars and the clattering souks. But I could not erase the images of the massacres. I carried on walking until well after dark and by the time I returned to my hotel had decided to try and find out more. One place in particular had struck me – a certain cave at Shadaddie. I rearranged my plans: I took Torkom’s map and a letter of introduction and left Aleppo for the desert.