Полная версия

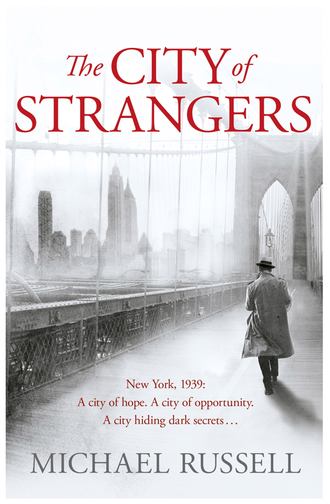

The City of Strangers

‘He’s not an Irishman for nothing,’ smiled Stefan.

‘Isn’t he? I’m not sure what he’s an Irishman for at all!’

Stefan didn’t reply. He could see the tension behind her words.

‘Sometimes I don’t know where he fits. In England he’s Irish and he champions Irish independence so aggressively he offends all his English friends. When he’s at home he defends England and doesn’t understand why all his Irish friends just want him to shut up. I don’t know where he belongs. I’m English. I never wanted to live here at all really, but I know more about Ireland now than he does. The only place he feels at home is with his regiment, whether it’s in England or East Africa or India. He’s spent more time away from us since I came to Whitehall Grove than he has with us.’

‘You know there’s not a farmer who isn’t struggling.’ Stefan said it reassuringly, but he knew the problems at Whitehall Grove were bigger than most farmers faced. He had tried to help with advice, but the place had its own creaking system of management that advice couldn’t change.

‘I wish the IRA hadn’t stopped burning down big houses. That would be the ideal answer. I was thinking of approaching Cumann na mBan directly to see if there was a waiting list I could get Whitehall Grove put on.’

She laughed the kind of careless laugh that she was so good at. Stefan still felt it was less careless than usual. But he didn’t ask her if anything else was wrong. If she wanted to tell him, she would tell him. They ate for several minutes in silence. Stefan was less easy with his life than he had been two days ago. And somehow it seemed the same for her. He felt it as they spoke. Something was changing.

They walked across O’Connell Bridge and turned along the Quays towards the hotel. They were staying at the Four Courts Hotel on Inns Quay, just along from Kingsbridge Station, where Stefan would be getting the train to Foynes the next morning. It was a cold night. Valerie’s arm was through his as it could never have been in Baltinglass. It was such a simple thing; but he missed it; a woman with her arm through his. It wasn’t very often that he allowed himself to look at the empty corners of his life. When he did he dismissed them with a wry grin or a few swear words, and usually it worked; but it was always something small that put the thought in his head, something like Valerie Lessingham’s arm now. They hadn’t spoken for a while. He was easier with silence than she was. But this silence was hers.

‘There will be a war. I really think so, don’t you?’

She spoke quite suddenly. It wasn’t such an odd topic to introduce, but Stefan wasn’t really sure where it had come from. Talk of war was everywhere. Most people had an opinion, even if in Ireland they were quick to shrug the idea off and change the subject; it wasn’t Ireland’s business anyway. What opinions there were, voiced or unvoiced, changed from day to day, with the news from Germany and Britain and Europe.

The belief that once Adolf Hitler’s demands were met, surely not entirely unreasonable demands after all, the dark clouds of conflict would blow away was strong in Ireland. The desire not to take sides, in what was increasingly seen as a confrontation between Britain and Germany, never mind the other countries in Europe threatened by Nazi expansion, had become a statement of nationhood. Independence and neutrality seemed to mean the same thing; too much criticism of Germany was seen as forelock-tugging subservience to Britain.

Stefan Gillespie’s views on Nazi Germany had little to do with forelock tugging. His mother’s family was German; he had been there himself. For him what was wrong in Germany wasn’t about Britain. But his opinions were not very popular; he had got used to not expressing them very loudly.

‘You know I’ve always thought that,’ he said quietly.

‘Simon doesn’t think it’s going to be very long. His last letter –’

‘He’s probably right.’

‘The regiment’s coming back from Kenya. They sail next week.’

‘Is that unexpected?’

‘They were meant to stay in East Africa till November.’

He nodded, but it didn’t feel like this conversation was about the war.

‘He won’t be coming home. I mean I’m sure he’ll come over at some point when he’s back in England, but it feels, well, he says it feels like something’s going to happen soon. We all know, we all damned well know!’

There was a stress in her voice that was unlike her.

They walked on in silence again. She held him tighter.

‘I can’t stay, Stefan. I wanted to tell you –’

He wasn’t sure what she was talking about; it felt like it could have been that night, but even before she spoke again, he knew it wasn’t at all.

‘I think I have to be where he is. I mean, I don’t know where he’ll be, but in England, I think I have to be in England. I’m not sure it’s what I want, for the children, even for me. Whatever’s happened between Simon and me, however far apart we’ve become – we have, I know we have. But I think I have to do what’s right now. He doesn’t agree. He doesn’t want us to leave Ireland at all. Obviously we’d all be safer here, but it matters more that we’re where – I mean I – I’m not putting it very well, am I?’

‘I think you’re putting it very well.’

It was strange, but he felt very close to her now.

‘I’m going to shut up the house and let the land. That way the estate will just about pay for itself. It means letting people go, and I’m not very happy about that. I know the children are going to hate it. My mother has a house in Sussex. It’s not huge, but we’ll all fit, just about. I wanted to tell you. I wanted you to understand. I think he needs us. He’d never say it. Perhaps it’s the first time he really needs us. He says he doesn’t want me to do any of this. But I am going to do it, Stefan. I hope it makes some sense?’

‘You don’t need to explain it all to me, Valerie.’

He knew she did of course; they were friends first.

They stopped. She turned towards him. She wasn’t a woman who cried; he wasn’t sure he had ever seen her cry. She was always bright, always laughing. Yet there were tears in her eyes now. He held her close. It was what she needed him to do. She turned her face up. They kissed, unaware of people around them, of traffic; unaware, it seemed, of the words just spoken. They said nothing as they walked into the Four Courts Hotel.

*

It was one o’clock in the morning when Stefan Gillespie woke up. Someone was hammering on the door of the hotel room. Valerie, in a deeper sleep, stirred next to him, then turned over. The hammering continued, a fist thumping rhythmically. He got out of bed, fumbling for clothes. He didn’t turn the lamp on. The banging stopped and a voice called through the door.

‘Wake the fuck up, Sergeant!’

He didn’t recognise the voice.

The fist started thumping again, slowly and impatiently. He walked to the door, doing up his trousers. The light by the bed suddenly went on.

‘What is it?’

Valerie was sitting up now.

‘God knows.’

He walked to the door and opened it slightly. The round, red face of Superintendent Gregory smiled in at him through the crack, so close that Stefan could taste the breath of whiskey and cigarettes coming off him.

‘I hope I’m not disturbing you, Sergeant.’

Gregory pushed hard against the door, and although Stefan stopped it opening fully, it opened wide enough for the Special Branch superintendent to see past him to the bed. Valerie was surprised, but unflustered. She simply pulled the bedclothes up and smiled pleasantly at the unknown man.

‘I didn’t know you had friends dropping in, darling?’

‘What the hell do you want?’ demanded Stefan.

‘There’s a bit of news, Stevie.’

Stefan stared at him, only now really fully awake.

‘Still, I did knock, that’s something. I’ll be in the bar.’

The smile had gone; the last words were an order.

Superintendent Gregory was sitting in the empty bar of the Four Courts Hotel when Stefan came down. He had a glass of whiskey in front of him. The sour, just woken night porter stood behind the bar next to a bottle.

‘Will you have a drink?’ said Gregory.

‘I won’t,’ was all Stefan replied as he sat down.

The superintendent turned to the night porter.

‘You can piss off now. Leave the bottle.’

The night porter put the bottle of Bushmills down on the table in front of the Special Branch man and walked back to the hotel lobby. The superintendent topped up his glass and then lit a cigarette. He took a few moments to do this. Stefan knew the game well enough; he thought Gregory wasn’t especially good at it.

‘I didn’t think there was a Mrs Gillespie?’

‘I’m flattered I’m worth finding out about, sir.’

‘I wouldn’t be too flattered. I like to know who I’m dealing with, that’s all. Still, it’s a relief to see a Mrs Gillespie of some sort on the hotel register. We’ve all been a bit concerned how friendly you are with your pals at the Gate, Messrs Mac Liammóir and Edwards. And she’s quite a looker.’

The game had to go on, and Stefan Gillespie decided it was better to let it run its course than to tell the Special Branch superintendent to fuck himself. Gregory was enjoying the fact that he had something on him; it was how the detective branch worked; with Special Branch it was almost the only way they did anything. The more you had on people, your colleagues included, the stronger you were. Stefan knew he used the same methods himself, though perhaps he didn’t use them in the same way. Favours and threats, knowing what other people didn’t know, the little nuggets of information you carried in your head until you had reasons to use them – it was part of the armoury, and the higher up you went, the more it mattered. If Terry Gregory didn’t quite know what to make of this country sergeant who didn’t seem to behave like a country sergeant should, it didn’t matter. He had something on him.

‘My father was always suspicious of Wicklow people. He said they’re all in bed with the English too much down there. That was a long time ago, but maybe he was right so. Course, you’re a Protestant yourself, aren’t you? Well, I suppose that makes it all right, you being in bed with the English.’

Gregory laughed, stubbing his cigarette and taking out another. He knew exactly who Valerie Lessingham was. He wanted Stefan to know he knew.

‘Isn’t her husband in the British army?’

‘I’m glad you’ve got time to investigate me, sir, when there’s so much on, but if there’s anything else you want to know, you can ask. It might save you some time. I know you’re busy. What’s happening with the investigation? Is there any news about Mrs Harris’s body yet?’

Superintendent Gregory shook his head.

‘Don’t try to fuck a fucker, son.’

But the game was over.

‘Ned Broy had a telegram from Mr McCauley, New York. It seems our Mr Harris wasn’t as enthusiastic about an invitation to come home for a chat as everyone thought. Not as I’d want to tell Ned I told him so, but I did.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘He’s gone. Not the biggest surprise, and I’m glad to say one that I don’t have any fecking responsibility for at all. I can kick that one upstairs.’

‘What happened?’

‘He walked out of the hotel, that’s all. And why wouldn’t he if he’s worked out what might be waiting for him in Dublin? So now he’s gone, the consul’s had to tell the New York police that we parked an axe-murderer in a hotel room with a bunch of queers to keep an eye on him, and never even mentioned it. And they were all worried about what we’d look like if something got into the American papers! I suppose we should be running the rosary through our fingers and praying Owen doesn’t get hold of an axe.’

He grinned. He was clearly taking some satisfaction in all this.

‘So does that mean I don’t go?’

‘Oh no, Stevie, the plane’s all booked.’

‘But I thought you –’

‘It’s not my mess. The Commissioner seems to think the NYPD will pick him up quick enough, so the job’s still the same. You might want to take a pair of handcuffs with you for the journey back though. Of course the NYPD will be pissed off. We’ve been playing the bollocks on their patch, however much we tell them it was all about Owen Harris doing us all a favour and helping us with our enquiries. They will know better by now.’

‘So what am I supposed to do?’ said Stefan.

‘Turn up and wait till they find him.’

‘And if they don’t?’

‘I’d say they will. No one seems to think he’s much in his head. But the lad might want to go easy over there. They’re as likely to shoot him as look at him, knowing what he’s done.’ Gregory laughed. ‘The place is full of Irish cops who love their mammies after all. They won’t take to him, I’d say. Not that anyone here would be too bothered if he came back in a coffin –’

‘I thought nobody really wanted me to go to New York –’

‘Now everybody wants you to go, me included.’

‘In case it’s a fuck up?’

‘Got it in one. You’re a bright lad, Stevie. But it’s already a fuck up. McCauley’s fuck up in New York, Ned Broy’s here. I don’t intend to make it mine. So the grand thing about you is you’re nobody. You don’t matter.’

‘What about the NYPD?’

‘What do they care? They’ll deliver you a prisoner, or if we’re lucky a box. And you’ve got the trip to look forward to, a hotel in New York. Jesus, you’ll be the toast of the sheep shaggers for miles around when you get back to Baltinglass. And it’s not all bad news, Sergeant. If you could maybe make it a box, you might even be up for promotion. It’d save on the trial and for my money, well, if I had to choose between being shot and being hanged –’

Terry Gregory drained the whiskey in his glass and stood up.

‘It’s an ill wind, eh Sergeant?’

He walked out to the lobby and into the street.

In the room Valerie was sitting up, reading. She laughed as Stefan came in.

‘What was all that about?’

‘The man I’ve got to bring back from New York has disappeared.’

‘So aren’t you going?’

‘They’ll find him. Well, that’s what the superintendent said.’

He shrugged. She said no more. As he sat down on the bed she stretched out her hand to touch his back. He sat there for a moment, not moving, feeling her fingers. He was aware how much he liked her. That was the thought in his head that made him smile. It wasn’t love between them, it never had been, but it wasn’t nothing, for either of them. He turned round and reached across the bed, stroking her hair. As he kissed her she pulled him slowly down on to her. Neither of them needed to speak now to know that this would be the last time they would make love.

6. West Thirty-Sixth Street

New York

Longie Zwillman stood at the counter in the window of Lindy’s diner on Broadway, between 49th and 50th. He kept his hat on and his overcoat done up, though it was warm enough in Lindy’s. He was thirty-five; he didn’t look older but somehow people felt he was older. There was age behind his eyes, and behind the half smile that was almost always on his lips there was nothing that suggested he found very much to laugh at. He was drinking the cup of coffee and eating the cheesecake Clara Lindermann had brought him personally.

It was busy in Lindy’s, but there was space at the window where Zwillman stood looking out, seemingly at nothing in particular. The two big men in homburgs who stood behind him would have made sure there was space, because Longie didn’t like people too close to him; even in a New York diner he expected the courtesy of space. But they didn’t have to make room for him. There was something about the way Longie held himself, and the way he looked at people when they came near him, that ensured he rarely had to ask for anything. He was a courteous man though; he seemed to inspire courtesy in others. Broadway wasn’t his territory; neither was Manhattan. He had come over from New Jersey. But he was respected here as he was respected everywhere. The work he had today crossed no lines. It wasn’t business. It was pest control, and he had an interest in that.

Outside the window, across the sidewalk, a truck stopped. It was a fish truck, one of the hundreds that pulled in and out of Fulton Market every night. The driver looked through the window at the man in the overcoat, eating the last forkful of Lindy’s cheesecake. Zwillman nodded. The truck drove on.

Longie finished his coffee and walked out on to Broadway, followed by the two big men. He sauntered down towards Times Square. He went almost unnoticed in the afternoon crowds bustling up and down around him, but not entirely. Several people recognised him and nodded respectfully. He nodded in return. Several times men walked up to him and spoke, in low tones of respect, asking after his health and the health of his family. They waited for him to stretch out his hand before they attempted to shake his. Two NYPD officers were among those who stopped and received an invitation to shake that hand.

In all the unseeing and indifferent noise of Broadway, Longie Zwillman walked like a secret island of calm and courtesy, or so it seemed. He knew who every one of the people who greeted him was, even out of his own fiefdom; and they were grateful for it. To know him and to be known by him was something. To lose those small favours was something else; after all respect and fear weren’t very different.

There was the beginning of darkness in the grey March sky over Times Square, and the lights all along Broadway were beginning to push the trash and the seedy corners out of sight. Crowds jammed around the 42nd Street subway as the people heading home from work met the people coming out to the theatres and movies, restaurants and clubs, or to do what most people did on Broadway, to be there and to walk about.

Pushing up from the subway, through the hundreds of New Yorkers streaming down, was a group of men, a dozen or so, all beered up for the evening in advance. They were rowdy already, laughing loudly and looking around with a kind of purpose and anticipation they seemed to find funny and exciting all at the same time; they were their own entertainment. But there was an aggression in their laughter that was more than just a bunch of guys with too much beer inside them. Several of them carried bundles of newspapers; one carried a furled flag; another carried billboards. Two of the men wore distinctive silver-grey shirts with a large L on the left side, in scarlet, close to the heart; the uniform of the Silver Legion of America. When they stopped on the corner of Broadway and 43rd they were quieter, gathering around the flags.

The newspapers were handed out, the billboards propped against a store front, the flags unfurled. The flag was the red L on silver; L for the Legion, L for Loyalty, L for Liberation. The placards bore scrawled headlines from the newspapers the men were selling: Social Justice, Liberation, National American. ‘Buy Christian Say No to Jew York!’ ‘Keep Us out of England’s War!’ ‘The Protocols of Zion and the End of America!’ ‘Roosevelt Public Enemy Number One!’ They moved along Broadway in twos and threes, hawking their papers, and shouting the headlines.

They were all New Yorkers, with names like other New Yorkers; mostly they were German and Irish names. But they weren’t only there to sell; they were looking for the enemies of America in the streets of their city; anyone they thought might be a Jew.

Dan Walker was already bored calling the headlines of the papers he never read anyway. He wanted another beer. Van Nosdall was a lot keener, thrusting out blue mimeographed slips as he moved through the crowds. ‘There’s only room for one “ism” in America, Americanism!’ ‘Democracy, Jewocracy!’ ‘Hey, Yid, no one wants you here! We’re coming for you!’ As he screamed ‘Coming for you!’ at an elderly couple, heading to the theatre, he formed his fingers into a pistol and laughed. ‘Pow!’ Dan Walker yawned.

‘Let’s get a beer for Christ’s sake!’

Then he stopped and smiled.

‘See the piece of shit there –’

He was looking at a boy of sixteen or seventeen, with a thin face and large, dark eyes. Anyone would have said he was Jewish. You could always tell a Jew of course, but this one was Jewish Jewish. He was staring at the two men with real anger in his face, and he wasn’t moving; he wasn’t trying to run the way he was supposed to. Dan Walker walked forward, with new enthusiasm for the slogans he had been leaving to Van Nosdall till now. He walked up to the youth, who was standing his ground, quietly unyielding.

‘Read Social Justice and learn how to solve the Jewish question.’

The Jewish youth nodded, unexpectedly.

‘OK, I’ll take one.’

It was an odd response; he should have already been running.

Dan Walker looked round at Van Nosdall.

Nosdall shrugged. He handed over a copy of Social Justice, and the youth handed him some change. As he opened the paper the youth glanced at the contents, with a look of deep seriousness. He turned a page.

‘I’ve been reading Father Coughlin’s articles about the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. It’s certainly some piece of work, some piece of work.’

He folded the newspaper up and put it in his pocket.

‘I’ve never seen shit like it. So this is what I’m going to do – I’m going to take it home and wipe my arse with every last, lying, fucking page.’

With that he ran, out into Broadway, through the traffic.

Dan Walker and Van Nosdall were already running after him. The bundle of papers was dropped. Dan put his fingers in his mouth and whistled shrilly. This was what they were all waiting for, this was real politics. And while a couple of men remained behind to pick up the newspapers the whole gang that had emerged from the subway only ten minutes earlier was racing through the blasting horns in pursuit of the young Jew. They had one now. And as long as they kept him in sight, they would run till they caught him.

He was in west 44th Street now, heading towards the Shubert Theatre. The street was quiet after Broadway and 7th Avenue; the theatres weren’t open yet. He looked round. They weren’t far behind. The other men had almost caught up with the two he had spoken to already. There were at least a dozen of them. He turned right abruptly, into the alley that ran between the Shubert Theatre and the Broadhurst. The gates were open. He stopped for a moment, catching his breath, and walked between the two theatres for a moment.

It was dark here now, and it was a dead end. At the top of the alleyway Dan Walker and Van Nosdall were standing, watching him. The youth turned round, and stood looking up at them. The other men were there now. They grouped together, extracting a variety of batons and coshes and knuckle dusters from their coats, grinning and joshing one another. They produced a wailing wolf-like howl, all together, and started to walk down the alley towards the Jew.

He seemed remarkably, unaccountably unafraid.

Quite suddenly a door out from the back of the Broadhurst Theatre opened. The youth gave a wave to the advancing party and walked into the theatre. The door closed. The men ran forward. It was a fire exit; it was heavy, blank; it had no lock or handle on the outside. Two of the newspaper sellers hammered on the door.

At first only one man turned round and looked back up the alley. A truck had just stopped there and in the light from 44th Street he could see a gang of men getting out of the back. Some of the others were looking round now; then they all were.

The whole street end of the alleyway was blocked by a small crowd; there were a lot of men there, twenty-five, thirty. They carried baseball bats and pickaxe handles. There was complete silence for some seconds. No one was hammering on the Broadhurst fire door now; no one was laughing. The men from the fish truck filled the alleyway. They moved in a line towards the men from the Silver Legion and the Christian Front, looking for healthy political debate.