Полная версия

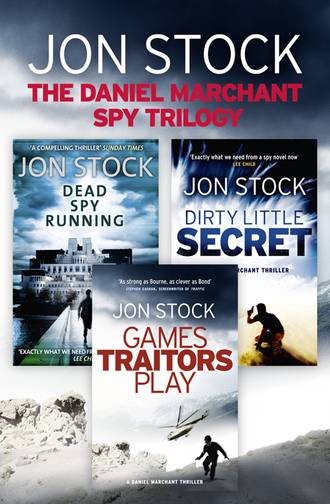

The Daniel Marchant Spy Trilogy: Dead Spy Running, Games Traitors Play, Dirty Little Secret

‘I’m offering you a deal,’ Chadwick said, swirling his Talisker around the glass. He was one of the safest pairs of hands in Whitehall, brought in at the end of a successful but unstartling career to steady the intelligence ship after the fiasco of Marchant’s departure. Evidence, Fielding concluded, that mediocrity can take you surprisingly far in big organisations like the Civil Service.

‘The Americans have agreed to drop their investigation of any meeting between Dhar and Stephen, providing they can have access to Daniel Marchant and we leave Dhar to them.’

‘Access?’

‘They want to sweat him.’

‘Why?’

‘Come on, Marcus. I know he was one of your best, but it’s bloody odd he was there at the marathon. They think he might be able to tell them something about Dhar. And, to be honest, the idea of someone taking Marchant off our hands is quite appealing. We all know he’s been drinking too much. The last thing the PM needs right now is another renegade spy on the loose.’

Fielding thought about defending Daniel Marchant again. Perhaps it was the effect of his gin and lime, but he was no longer as troubled by Chadwick’s proposal as he might have been. A part of him resented having to protect Marchant any longer, given the headache his suspension had caused. Chadwick was right: Marchant had been the most promising case officer of his generation, just the sort of young blood the Service was trying to attract. But Fielding knew, too, that his suspension was entirely because of the accusations swirling around his father. And he needed those accusations to go away: they were continuing to cause too much damage to the Service. The sooner the Americans forgot about any meeting between the former Chief and Dhar, the better for everyone.

There was only one concern, and that was the ‘enhanced’ interrogation techniques favoured by the CIA. The new President might have banned torture, but old habits die hard in Langley. Despite everything, Marchant was still one of his own, and right now he was fragile.

‘He mustn’t leave the country,’ Fielding said, finishing his gin. ‘And I want him back alive.’

10

Leila headed back to London that night, leaving Marchant to dwell on Fielding’s visit over a bottle of malt she had smuggled in with her. He knew he was drinking too much. The training runs with Leila, the impulsive decision to run the marathon, had been an attempt to impose some routine on his life, which had lost all shape since his father’s death. He had never been fitter than when he was working for MI6. The drinking dulled the pain of loss, but it also dragged him back to another life, to dissolute, carefree days at the Nairobi Press Club.

The first weeks of his suspension had been the toughest. In his sober hours, Marchant had thought only of the mole who had supposedly penetrated MI6. It was his way of grieving, channelling his anger. Rising at dawn, head bursting, he had paced the empty streets of Pimlico, holding the rumours about his father up to the early-morning light, looking at them from every possible angle. He would stand on Vauxhall Bridge, watching the barges pass below before turning to look up at Legoland and the buttressed windows of the Chief’s office. Had the whole thing been cooked up as a Machiavellian way of removing his father, or was there a genuine possibility that Al Qaeda had infiltrated MI6?

The terms of his suspension meant that he wasn’t allowed to step inside Legoland, or to talk with colleagues about work, or to travel overseas. All his cover passports had been seized. His mornings had been spent in internet cafés around Victoria station (he didn’t trust the computer at his flat on Denbigh Street), going over each of the attacks again and again, looking for something that might link a cell based in South India to anyone in MI6, a Legoland colleague with connections to the subcontinent.

Now, at last, he had that link, but it was between his own father and Salim Dhar. Never once had it crossed Marchant’s mind that his father had brought suspicion upon himself. Fielding was right: meeting Dhar privately was an irregular thing to have done. And Marchant knew, as Leila’s whisky burnt his throat, that he too would have to meet him, wherever he was. It was the only way to clear his father’s name. He needed to ask Dhar why the Chief of MI6 had run the risk of meeting with him. The consequences of such an encounter could prove equally disastrous for him, but the reality was that he didn’t have much to lose.

As he gazed out across the Wiltshire countryside towards the woods beyond the canal, a grey heron lifted itself heavily from the water and rose into the air. His father used to say that they were like B-52s, but then he had always had a thing about bombers. During the Cuban Missile Crisis he had driven down to Fairford and watched them standing on the end of the runway, engines running, waiting for the order.

Marchant remembered the morning his father had called him with the news that he was to step down as Chief. The power and authority had gone from his voice, as if he had been using a megaphone all his life and someone had suddenly switched it off. Marchant had taken the call at Heathrow airport, on his way back from Mogadishu to London for Christmas.

‘Have you cleared immigration?’ his father had asked, almost absent-mindedly.

‘I’m waiting for a taxi. Why? Is everything all right, Dad?’

‘Take the Underground as far as Hammersmith, then a minicab from that place on Fulham Palace Road we used to use. Ask for Tarlton. They’ll know.’

‘Dad, what is this? Is everything OK?’

‘I’ve been put out to pasture. Watch yourself.’

Marchant had immediately gone on his guard again, as if in a foreign airport. He moved swiftly down to the Underground, trying to work out the implications of their conversation, for his father, for him. He knew pressure had been building in recent weeks. There had been questions in the House about the incompetence of Britain’s intelligence services, aggressive newspaper leaders about the wave of attacks and what more should have been done to prevent them.

His father paid off the minicab in cash, and insisted on taking his son’s two bags. It was a cold December day, and the apple and cherry trees at the front of the house were laced with frozen cobwebs. A thin twist of smoke rose from the chimney. The house was in effect two Cotswold cottages knocked together, surrounded by lawns and a meandering drystone wall. It was a private location, half a mile out of Tarlton, a small hamlet near Cirencester. Marchant always felt strange when he was here. The house had been the only constant in his shifting childhood, a place where they came for brief respites from foreign postings, a home he had once shared with his brother. Its Englishness was overwhelming, not just because of its Cotswold prettiness, but because it had come to represent all that he missed about home: new-mown grass, autumn bonfires, orchards. And, of course, it had always disappointed, unable to live up to childhood dreams of Albion.

‘Good of you to come,’ his father said, walking through the back door in front of Marchant. ‘Mind if we go for a drive?’

Ten minutes later, they were speeding through the cold open countryside in his 1931 Lagonda, barely able to hear each other above the roar of the two-litre engine. Frost had sharpened the hedgerows, and the road was black with hidden ice. But Stephen Marchant didn’t seem to mind, wrapped up in a thick woollen scarf and gloves. Daniel sat next to him. He had forgotten how cold a car could feel.

‘Can’t trust the house,’ his father said, changing down the gears as they approached a junction. Home, Marchant knew, had been wired to a level of protection befitting the Chief’s weekend retreat. Now that security was working against him.

‘MI5?’ Marchant asked, the smell of musty canvas and hot oil taking him back to another distant part of his childhood. He and his father had always been close, both of them at ease in each other’s company, seldom needing to explain or open up. Even when Marchant had been expelled from school, his father hadn’t been angry, just annoyed that he had been caught.

‘I’m becoming a threat to national security,’ he shouted, releasing the brake lever on the side of the car and accelerating away towards Avening. Marchant hoped he would age as well as his father, whose silver hair was blowing about in the strong breeze. He had thick, fair eyebrows and a compact, square face, like a barn owl, Marchant always thought. And then there were those famous family ears, which had only got longer, more distinguished, with age. Tribal lobes, his father had once called them.

After twenty minutes, Stephen Marchant pulled the Lagonda up in a lay-by at the top of Minchinhampton Common, on the brow of a hill looking west towards Bristol. He switched off the engine and they sat there for a few minutes in silence, absorbing the timeless landscape as steam rose off the bonnet. Below them the Cotswolds stretched out in a necklace of icy hamlets, threaded with quiet country lanes, each with its handsome manor house, enduring church, frosted green. Thin drifts of snow covered the shaded corners of fields.

‘I look at this and wonder out of which pore of our beautiful country it’s seeping from,’ Stephen Marchant began. A bead of moisture had gathered on the end of his cold nose. ‘Do you know what they said?’

‘Tell me,’ Marchant replied, noticing the emotion that had slipped into his father’s voice.

‘That they can no longer be sure my interests coincide with the country’s.’ He paused, struggling to keep control. ‘Thirty years’ service and I have to listen to a group of jumped-up pricks in shorts telling me that.’

‘And it’s all coming from the DG?’ Daniel asked.

‘Of course. Apparently I’m obsessed with the enemy within, and have taken my eye off the greater threat.’

‘Dinner at the Travellers didn’t do the trick, then.’

‘God, no. Total disaster. She’s not like the women you and I know, Daniel. This one’s got balls, and I’ve been shafted, well and truly. They don’t want me back in the office after Christmas. I’m afraid they’re also talking about suspending you. Sins of the father. I’m so sorry.’ Marchant turned away, his mind racing instinctively to calculate the threat, assess the damage. He hadn’t expected it to affect him. Then he stopped, guilty that he had thought of himself rather than his father, whose career was in tatters after half a lifetime of service.

‘Don’t worry about me. You know I’ve never asked for help. I can look after myself.’

‘The Service can’t. If MI5 gets its way, Legoland will be sold off to the Japanese tomorrow and turned into a Thameside hotel. Come on, the idiots have arrived.’

Marchant looked behind them, and saw a white saloon car driving slowly up the hill.

‘Do you know the best way to shake off a tail?’ his father asked, firing up the Lagonda again in a plume of blue smoke. ‘Better than anything they might have taught you at the Fort?’

‘What?’ Marchant said, watching the car in the mirror as it slowed to a crawl four hundred yards behind them, its exhaust loitering in the cold air.

‘Drive faster than them.’

11

The gang of Year Five boys in the corner of the playing field knew all of the helicopters that flew through the Wiltshire airspace above their primary school: Chinooks were their favourite, flying low down the route of the canal, the sound of their twin blades reverberating like thunder in their tender eardrums. They knew their Merlins from their Sikorski Pumas, and barely commented these days on the black-and-yellow Wiltshire Police helicopter, which flew in every Friday for low-level practice over Bedwyn Brail. So when the boys saw the MD Explorer coming in towards the village from Hungerford, it was such a familiar sight that nobody noticed that it was a Thursday, not a Friday.

Half a mile south-west of the school, Daniel Marchant crossed over the two bridges and turned right onto the towpath of the Kennet canal. He smiled to himself as he remembered how his father had dropped down from Minchinhampton at more than 90 mph, the Lagonda’s low chassis threatening to shake itself apart as they raced through the frosty hedgerows without any real brakes, until their pursuers had finally given up.

Marchant wasn’t sure if he could run faster than his minders, but he wanted to find out. The marathon was five days ago, and this was his first run since he had arrived at the safe house. He knew he couldn’t keep going like this: the drinking followed by the guilt-runs. One of them had to prevail. The babysitters from MI6 had been replaced the previous evening by heavier-built types from MI5. Relations chilled accordingly, and conversation had all but dried up.

Marchant wasn’t unduly worried by the change of guard. At worst, he assumed that he might be subjected to Wylie again, the man who had interviewed him at Thames House. More worrying was the silence from Leila. He had no means of contacting anyone in the outside world. There was no phone at the house, no computer or internet connection, and the babysitters kept their mobiles strapped to their expansive waistlines.

His plan this morning, as he gradually increased his stride, was to stretch the two from MI5, see how long they could cope with a six-minute-mile pace. They hadn’t been keen on the idea of a run, but relented when Marchant agreed to show them on a map his exact route to the nearby village of Wilton and back. They preferred a shorter loop, along the canal towpath, up through the woodland known as Bedwyn Brail, and then back along the lanes into the village. Marchant agreed, tickled by the idea of pushing these two to their limits. The fitness levels in MI6 had always been greater than those of MI5, whose gym was no match for the one that glistened in the basement of Legoland, out of sight of Whitehall’s bean counters.

But it was not proving nearly as entertaining as Marchant had hoped. His whole body hurt like hell. And both men from MI5 responded with unnerving ease to his initial kick, and he soon found them on his shoulder.

‘Don’t be a muppet, marathon man,’ one of them said, barely out of breath.

Without answering, Marchant kicked again, turning off the towpath, as agreed, and carving out a diagonal route up the hillside towards the Brail. Near the top of the hill, he glanced over his shoulder and saw the lead minder floundering at the bottom of the slope. It looked as if he had slipped. Exhilarated to be alone for the first time since Sunday, Marchant upped his pace again.

It was as he crested the hill that he became aware of the black MD Explorer hovering in the field behind him, to his left. He slowed a little, taking in the scene, assessing the situation. His first thought, as he read the yellow police lettering on the side of the helicopter, was that he had stumbled on an incident of some kind. But seconds later, as his two minders drew level, the helicopter was no longer hovering, but tracking him across the field.

Marchant looked out across the stretch of farmland in front of him. It was at least two hundred yards to the woods on the far side, but he thought he could make it to the safety of the trees if he ran hard. He glanced above him and saw the face of the pilot in his helmet and visor, looking down at him with wasp-eyed indifference. At the same moment, he felt a minder on his shoulder and shrugged him off. The man fell away, swearing as he stumbled, but before Marchant could accelerate, the other minder was on his back, dragging him down.

They seemed to slow as they fell, Marchant rolling the man over so that they hit the ground with him on top. All around them, the flattened grass danced in the helicopter’s downdraft. He grabbed the man by his hair and pushed his face hard into a flintstone lying in the earth. For a moment there was stillness. Marchant stood up and started to run, aware of the first man coming up behind him, the helicopter above. The woods suddenly seemed a mile away.

Twenty yards from the trees, Marchant began to believe that he could make it. Once he was inside the Brail, the helicopter would be useless, providing he kept to the cover of the trees. But he still had the man on his right. Five yards short of the trees, he saw a branch on the ground, heavy with the rain of winter. He veered off his path and picked it up, arcing the sodden log behind him in the same movement. As it collided with the side of the man’s face, knocking him backwards, the blades above him seemed to grow louder, roaring their disapproval. Marchant sprinted into the dark woods, sidestepping through the trees like a street thief eluding his pursuers.

He had run barely thirty yards when the woods opened up into a small clearing. The helicopter swooped low overhead, touching down on the patch of grass in front of him long enough for two more men to jump out. Tired now, Marchant turned and headed back into the woods, but he was soon being dragged towards the helicopter, the smell of aviation fuel filling the air.

Marchant calculated that he had been in the air for fifteen minutes before the helicopter touched down, which made Fairford the most likely airfield. It was run by the Americans, who had spent $90 million extending the main runway for its B-2 Spirit Stealth bombers and the Space Shuttle. He suspected he would be travelling in something smaller. He couldn’t confirm which airfield it was for himself because of the hood over his head, and he couldn’t hear any cockpit talk because a pair of headphones had been slipped over the hood. His hands had been tied tightly behind his back, and his feet were bound together too. But he wasn’t in any real discomfort, not yet.

Mentally, he was as together as anyone could be who knew he was in the process of being extraordinarily renditioned by the CIA. It was the only logical reading of the situation he found himself in, given that it was unlikely MI5 or even MI6 would use such extreme methods on one of their own. During his short flight he had concluded that Fielding, for reasons as yet unclear, must have agreed to hand over the keys of the Wiltshire safe house to MI5, who had duly allowed the Americans to remove him for their own questioning. What made his stomach tighten now, as he lay on the cold metal floor of the stationary helicopter, was the thought of the physical and mental pain that lay ahead.

12

The undisputed waterboarding world champion was Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. Marchant knew this thanks to a flippant email that had leaked its way from Langley to Legoland. The architect of 9/11, the Bali nightclub bombings and a thwarted attack on Canary Wharf, ‘KSM’ (as the CIA called him) deserved some silverware for his efforts, but instead Al Qaeda’s number three had to make do with grudging respect from his interrogators. Two minutes thirty seconds–there were no officials, but that was the time clocked when he was waterboarded in early March 2003. At two minutes thirty-one seconds he broke, finally believing that he was about to drown. He screamed like a baby and filled his diaper. As the email concluded: the smell of victory is the whiff of excrement.

Marchant knew everything there was to know about waterboarding, a method of interrogation that had been favoured by the Gestapo and, thanks to the CIA, had been enjoying a revival in recent years, until the new President put a stop to it. The sensation of water being poured onto his mouth and nose convinced the victim that he was about to drown, triggering an immediate, involuntary gagging response. Because the feet were raised higher than the head, however, water did not flood the lungs, thereby avoiding death and allowing governments to categorise it as an enhanced interrogation technique rather than torture.

Marchant knew all about the three different levels, the same unrelenting message that each sends to the brain, the convenient absence of physical marks, the acute mental trauma that can be triggered for years afterwards: by taking a shower, washing up, watering the windowbox.

What his interrogators didn’t know was that Marchant had broken KSM’s record during his survival training course at the Fort. It wasn’t official, because Marchant had been aware, at least before the water started flowing, that it was an exercise. KSM had thought he was about die. But two minutes fifty seconds was still a record of sorts, good enough to make him the toast of the Fort. As Marchant was told afterwards, no CIA agent who had tested the technique on himself had lasted more than fourteen seconds.

Marchant liked to joke that his ability to endure waterboarding was honed at birth–he was born underwater. His mother had told him that he came out with his eyes open, looking around like a startled carp. Others, like Leila, said it was his Indian childhood: a case of Yogic mind over matter. As he lay in the dark now, his tightly bound feet raised above his hooded head on a cold metal table, he tried to recall the banter in the Portsmouth pub afterwards: his voice sounding funny because of the water still blocking his nose; Leila’s tenderness beneath the bravura; her wet-mouthed kiss that he thought would asphyxiate him.

He suspected he was in Poland, or maybe Romania. The CIA had been ordered to shut down its network of black sites, but Langley was in no rush. It knew the bureaucrats would struggle to verify the closure of facilities that had never officially existed. After the helicopter had touched down, he had been escorted, still blindfolded, across the tarmac to another plane, a Gulfstream V, he guessed. Dubbed the Guantanamo Bay Express by enemy combatants, his flight had lasted two hours, although for Marchant, travelling in detainee class (complimentary boilersuit and adult nappies), it had felt like a lifetime.

He heard the two men enter his cell, closing the door behind them. Waterboarding was just a trick of the mind, he told himself, involuntarily flexing his fingers. They said nothing as they checked his wrists, bound tightly in shackles by his side, and pulled the cotton hood further down over his head. In a moment they would pour water continually over his porous hood.

When the water came, sooner than he expected, Marchant instinctively tried to turn his head away, but the man on his left held his jaw firmly while the other poured water onto his face, and then over his chest and legs, soaking his boilersuit. He could feel the panic rising. There was his twin brother, lying at the bottom of the pool in Delhi, staring up at him through the clear water. He screamed for the ayah, jumped in and tried to grab his brother’s arm. Sebastian, barely six years old, stared back at him, his hair floating like a rockpool anemone, unaware that he was about to drown.

The flow of water was constant, Marchant told himself, struggling to control his breathing. That suggested that they were using a hose rather than a watering can, the preferred method at the Fort. He screamed again, at his interrogators, at his mother, who had come running out from the house, but his cries were muffled by the damp cotton hood pressing down against his face. He could feel the water starting to seep through, running up his nose and into his mouth. It was warm, just as the training manual stipulated. This was an exercise, he told himself: they weren’t going to kill him. The new President wouldn’t allow it.

‘Where’s Salim Dhar?’ one of the Americans shouted, twisting Marchant’s jaw violently towards him. Marchant was shocked by how young the voice–Midwest–sounded. ‘Tell us where he is and your brother will live.’

Marchant said nothing, waiting for Sebastian to start breathing, watching his mother bent over the tiny body. ‘Is he OK?’ he begged her. ‘Is Sebbie going to be OK?’

His interrogator held the hose closer to his mouth. ‘Where’s Salim Dhar?’ he repeated.

Why were they asking him? He wasn’t his father. The water started to pour in through the cotton hood. Marchant kept his lips pressed tightly together, breathing in slowly through his nose, but that was what he was meant to do: the water flooded up both nostrils. His lungs were bursting, desperate now for air. He tried twisting his head away, then he saw Sebastian spluttering back to life, vomiting the pool water, his tiny chest convulsing, coughing into his mother’s perfumed embrace.