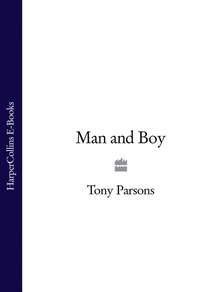

Полная версия

The Complete Man and Boy Trilogy: Man and Boy, Man and Wife, Men From the Boys

‘I can’t explain it. Not even to myself.’

‘You should try. Because if you don’t understand what happened to us, you’re never going to be happy with anyone.’

‘You explain it to me.’

She sighed. You could hear her sighing all the way from Tokyo.

‘We had a marriage that I thought was working, but you thought was becoming routine. You’re a typical romantic, Harry. A relationship doesn’t measure up to your pathetic and unrealistic fantasy so you smash it up. You ruin everything. And then you’ve got the nerve to act like the injured party.’

‘Who’s providing the armchair psychology? Your Yank boyfriend?’

‘I’ve discussed what happened with Richard.’

‘Richard? Is that his name? Richard. Hah! Jesus Christ.’

‘Richard is a perfectly ordinary name. It’s certainly no stranger than Harry.’

‘Richard. Rich. Dicky. Dick. Old Richard Dicky-dickhead.’

‘Sometimes I look at you and Pat, and I honestly can’t tell which one is the four-year-old.’

‘It’s easy. I’m the one who can pee without getting anything on the floor.’

‘Blame yourself for all this,’ she said, just before she hung up. ‘It happened because you didn’t appreciate what you had.’

That wasn’t true. I was smart enough to know what I had. But too dumb to know how to keep it.

Like any couple living under the same roof, we soon developed our daily rituals.

Just after daybreak, Pat would stagger bleary-eyed into my bedroom, asking me if it was time to get up. I would tell him that it was still the middle of the bloody night and he would climb into bed with me, immediately falling asleep in the spot where Gina used to sleep, throwing his arms and legs about in his wild, childish dreams until eventually I would give up trying to get any more rest and get up.

I would be reading the papers in the kitchen when Pat dragged himself out of bed, and I would immediately hear him sneak into the living room and turn on the video.

Now that Pat was out of nursery and I was out of a job, we could take our time getting ready. But I was still reluctant to let him do exactly what he wanted to do, and what he wanted to do was watch videos all day long. So I would go and turn the video off and escort him to the kitchen, where he would toy with a bowl of Coco Pops until I gave him his freedom.

After we were washed and dressed, I would take him over the park on his bike. It was called Bluebell, and it still had the stabilisers on. Pat and I sometimes discussed removing the stabilisers and trying to ride it with just two wheels. But it seemed like an impossible leap forward to both of us. Knowing when the time was right to remove a bike’s stabilisers was the kind of thing that Gina was good at.

In the afternoons my mother would usually collect Pat and this would give me a chance to do some shopping, clean up the house, worry about money, pace the floor and imagine Gina moaning with pleasure in the bed of another man.

But in the morning, we went to the park.

Sixteen

Pat liked to ride his bike by this open-air swimming pool at the edge of the park.

The little pool was kept empty all year round apart from a few weeks early in the summer when the council grudgingly filled it with heavily chlorinated water which made the local children smell as though they had been dipped in industrial waste.

Long before the summer was over, the water would be drained from the pool and the odd supermarket trolley fished from the bottom. We were only in the middle of August, but the little pool had already been abandoned for another year by everyone apart from Pat and his Bluebell.

There was something depressing about the almost permanently empty pool. It was in a desolate part of the park, nowhere near the adventure playground where children screamed with delight, or the little café where mums and dads – but they were mostly mums – drank endless cups of tea.

But the little asphalt strip that surrounded the pool was somewhere for Pat to ride his bike without having to plough through the discarded kebabs, used condoms and dog shit that littered most of the park. And to tell you the truth, it suited me to be away from all those mums.

I could see what they were thinking when we entered the park every morning.

Where’s the mother?

Why isn’t he at work?

Is that really his kid?

And of course I could understand their concern, most of the perverts in this world being the proud owner of a penis. But I was tired of feeling that I should apologise for taking my son to the park. I was tired of feeling like a freak. The empty swimming pool suited me fine.

‘Daddy! Look at me!’

Pat was on the far side of the pool, breathing hard as he paused by the stubby little diving board that poked out over the empty deep end.

I smiled from the bench where I sat with my paper, and as soon as he saw that he had my attention he shot off again – eyes shining, hair flying, his little legs pumping furiously as he tore around the pool on Bluebell.

‘Stay right away from the edge!’

‘I will! I do!’

For the fifth time in five minutes, I read the opening sentence of an article about the collapse of the Japanese economy.

It was a subject that had come to interest me greatly. I felt sorry for the Japanese people because they seemed to be living in a system which had failed them. But mixed with the human sympathy was a kind of relish. I wanted to read about banks closing down, disgraced CEOs bowing and weeping at press conferences, freshly unemployed expatriates heading for Narita airport and the next flight back home. Especially that. But I couldn’t concentrate.

All I could see was Gina and Richard, although I couldn’t see them very well. Gina was starting to slip out of focus. She wasn’t my Gina any more. I couldn’t imagine the place where she lived, the office where she worked, the little noodle joint where she had her lunch every day. I couldn’t picture any of it. And it wasn’t just her new life that was difficult for me to see. I could hardly see her face in my mind any more. But if Gina was a blur, then Richard was a complete blind spot.

Was he younger than me? Richer than me? Better in bed than me? I would have liked to think that Gina was stepping out with an impotent bankrupt on the verge of senility. But I could see that was probably just wishful thinking on my part.

All I knew was that he was married. Yet even that was suspect – what the fuck did semi-separated mean? Was he still living with his wife? Was she American or Japanese? Did they still sleep together? Did they have kids? Was he serious about Gina or just stringing her along? And would I like it more if he saw her as a casual fling or as the love of his life? Which one would hurt me the most?

‘Look at me now!’

The sight made me freeze.

Pat had very carefully edged his bike out on to the diving board. He was balanced above a ten-foot drop to the pockmarked concrete at the bottom of the pool. Either side of Bluebell, his legs were at full stretch as he steadied himself with the toes of his dirty trainers. I hadn’t seen him looking so happy for weeks.

‘Stay right there,’ I called. ‘Don’t move.’

His smile faded when he saw me start running towards him. I should have gone slower. I should have pretended that nothing was wrong. Because when he saw the look on my face, he started trying to back off the diving board. But it was easier to get on than off and the world seemed to slip into slow motion as I saw one of Bluebell’s stabilisers slide off the side of the diving board, spin in the air for a moment, and then Pat’s little feet inside the dirty trainers were off balance and scrambling for something that wasn’t there, and I was watching my boy and his bike falling headfirst into that empty swimming pool.

He was lying under the diving board, the bike on top of him, the blood starting to spread around his mop of yellow hair.

I waited for him to start screaming – just as he had screamed the year before when he was using our bed for a trampoline, bounced right off and smashed his head against the chest of drawers, and just as he had screamed the year before that, when he had overturned his pushchair by standing up in it and trying to turn around to smile at me and Gina, and just as he had screamed on all the other occasions when he had banged his head or fallen flat on his face or grazed his knees.

I wanted to hear him crying out because then I would know that this was just like all the other scrapes of childhood. But Pat was totally silent, and that silence gripped my heart.

His eyes were closed and his pale, pinched face made him look like he was lost in some bad dream. The dark halo of blood around his head kept growing.

‘Oh Pat,’ I said, pulling the bike off him and holding him far more tightly than I should have. ‘Oh God,’ I said, taking my mobile phone out of my jacket with fingers which were sticky from his blood, frantically tapping in the PIN number and hearing the beep-beep-beep sound of a flat battery.

I picked up my son.

I started to run.

Seventeen

You can’t run far with a four-year-old child in your arms. They are already too big, too heavy, too awkward to carry with any speed.

I wanted to get Pat home to the car, but I staggered out of the park knowing that wasn’t going to be quick enough.

I burst into the café where we had eaten green spaghetti, Pat still pale and silent and bleeding in my arms. It was lunch time, and the place was full of office workers in suits stuffing their faces. They stared at us open-mouthed, forks twirled with carbonara suspended in mid-air.

‘Get an ambulance!’

Nobody moved.

Then the kitchen doors flew open and Cyd came through them, a tray piled with food in one hand and her order pad in the other. She looked at us for a moment, flinching at the sight of Pat’s lifeless body, the blood all over my hands and shirt, the blind panic on my face.

Then she expertly slid the tray on to the nearest table and came towards us.

‘It’s my son! Get an ambulance!’

‘It will be quicker if I drive you,’ she said.

There were white lines on the hospital floor that directed you to the casualty department, but before we got anywhere near it we were surrounded by nurses and porters who took Pat from my arms and laid him on a trolley. It was a trolley for an adult, and he looked tiny on it. Just so tiny.

Tears came to my eyes for the first time, and I blinked them away. I couldn’t look at him. I couldn’t stop looking at him. Your child in a hospital. It’s the worst thing in the world.

They wheeled him deeper into the building, under the sick yellow strip lights of crowded, noisy corridors, asking me questions about his birthday, his medical history, the cause of his head wound.

I tried to tell them about the bike on the diving board above the empty swimming pool, but I don’t know if it made much sense to them. It didn’t make much sense to me.

‘We’ll take care of him,’ a nurse said, and the trolley banged through green swing doors.

I tried to follow them and caught a glimpse of men and women in green smocks with masks on their faces, the polished chrome of medical equipment, and a kind of padded slab where they laid him down, that slab as thin and ominous as a diving board.

Cyd gently took my arm.

‘You have to let him go,’ she said, and led me to a bleak little waiting area where she bought us coffee in polystyrene cups from a vending machine. She filled mine with sugar without asking if that’s how I liked it.

‘Are you okay?’ she said.

I shook my head. ‘I’m so stupid.’

‘These things happen. Do you know what happened to me when I was about that age?’

She waited for my reply. I looked up at her wide-set brown eyes.

‘What?’

‘I was watching some kids playing baseball and I went up and stood right behind the batter. Right behind him.’ She smiled at me. ‘And when he swung back to hit the ball, he almost took my head off. That bat was only made of some kind of plastic, but it knocked me out cold. I actually saw stars. Look.’

She pushed the black veil of hair off her forehead. Just above her eyebrow there was a thin white scar about as long as a thumbnail.

‘I know you feel terrible now,’ she said. ‘But kids are tough. They get through these things.’

‘It was so high,’ I said. ‘And he fell so hard. The blood – it was everywhere.’

But I was grateful for Cyd’s thin white scar. I appreciated the fact that she had been knocked unconscious as a child. It was good of her.

A young woman doctor came and found us. She was about twenty-five years old, and looked as though she hadn’t had a good night’s sleep since medical school. She was vaguely sympathetic, but brisk, businesslike, as honest as a car wreck.

‘Patrick is in a stable condition, but with such a severe blow to the head we have to take X-rays and a brain scan. What I’m worried about is the possibility of a depressed fracture to the skull – that’s when the skull is cracked and bony fragments are driven inward, causing pressure on the brain. I’m not saying that’s happened. I’m saying it’s a possibility.’

‘Jesus Christ.’

Cyd took my hand and squeezed it.

‘This is going to take a while,’ the doctor said. ‘If you and your wife would like to stay with your son tonight, there’s time to go home and get some things.’

‘Oh,’ Cyd said. ‘We’re not married.’

The doctor looked at me and studied her chart.

‘You’re Patrick’s father, Mr Silver?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’m just a friend,’ Cyd said. ‘I should go,’ she told me, standing up. I could tell that she thought she was getting in the way. But she wasn’t at all. She was the only thing keeping me from falling apart.

‘And the child’s mother?’ the doctor asked.

‘She’s out of the country,’ I said. ‘Temporarily out of the country.’

‘You might want to call her,’ the doctor said.

My mother had been crying, but she wasn’t going to do it in public. She always saved her tears for behind closed doors, for the eyes of the family.

At the hospital she was all gritty optimism and common sense. She asked practical questions of the nurses. What was the risk of permanent damage? How long before we would know? Was it okay for grandparents to stay the night? It made me feel better having her around. My dad was a bit different.

The old soldier looked lost in the hospital cafeteria. He wasn’t used to sitting and waiting. He wasn’t used to situations that were beyond his control. His thick tattooed arms, the broad shoulders, his fearless old heart – they were all quite useless in here.

I knew that he would have done anything for Pat, that he loved him with the unconditional love you can probably only feel for a child, a love that’s far more difficult to feel when your perfect child has grown into one more fallible adult. He loved Pat in a way that he had once loved me. Pat was me before I had a chance to screw everything up. It gnawed at my father inside that all he could do was sit and wait.

‘Does anyone want any more tea?’ he said, desperate to do something, anything to make our miserable lot a little better.

‘We’ll have tea coming out of our ears,’ my mum said. ‘Just sit down and relax.’

‘Relax?’ he snorted, glaring at her, and then deciding to leave it.

He flopped into a cracked plastic chair and stared at the wall. There were bags under his eyes the colour of bruised fruit. Then after five minutes he went to get us some more tea. And as he waited for news of his grandson and sipped tea that he didn’t really want, my father seemed suddenly old.

‘Why don’t you try Gina again?’ my mother asked me.

I don’t know what she was expecting. Possibly that Gina would get on the next plane home and soon our little family would be united once more and forever. And maybe I hoped for that, too.

But it was no good. I went out to the reception area and called Gina’s number, but all I got was the strange purring sound of a Japanese telephone that nobody answers.

It was midnight in London, which made it eight in the morning in Tokyo. She should have been there. Unless she had already left for work. Unless she hadn’t come home last night. Her phone just kept on purring.

This was how it was going to be from now on. If I had spoken to Gina, I know that her strength and common sense would have got the better of any fear or panic. She would have been more like my mum than my dad. Or me. She would have asked what had happened, what were the dangers and when would we know. She would have found out the time of the next flight home and she would have been on it. But I just couldn’t reach her.

I hung up the phone, knowing that the rest of our lives were going to be like this, knowing that things had gone too wrong to ever be the way they were, knowing that we were too far away from each other to ever find our way back.

Eighteen

The doctor came looking for me at five in the morning. I was in the empty cafeteria, nursing a cup of tea that had gone cold hours ago. I stood up as she came towards me, waiting for her to speak.

‘Congratulations,’ she said. ‘Your son has a very hard head.’

‘He’s going to be okay?’

‘There’s no fracture and the scan is clear. We’re going to keep him in for observation for a few days, but that’s standard procedure when we’ve put twelve stitches in a four-year-old’s head wound.’

I wanted that doctor to be my best friend. I wanted us to meet up for dinner once a week so she could pour out all her frustrations with the NHS. I would listen and I would care. She had saved my son. She was beautiful.

‘He’s really all right?’

‘He’ll have a sore head for a few weeks, and a scar for life. But, yes, he’s going to be okay.’

‘No side effects?’

‘Well, it will probably help him get girls in fifteen years’ time. Scars are quite attractive on a man, aren’t they?’

I took her hands and held them a bit too long.

‘Thank you.’

‘That’s why we’re here,’ she smiled. I could see that I was embarrassing her, but I couldn’t help it. Finally I let go. ‘Can I see him?’

He was at the far end of a ward full of children. Next to Pat there was a pretty little five-year-old in Girl Power pyjamas with her hair all gone from what I guessed was chemotherapy. Her parents were by her side, her father asleep in a chair, and her mother at the foot of the bed, staring at her daughter’s face. I walked quietly past them to my son’s bed, knowing that I had been wrong to wallow in self-pity for so long. We were lucky.

Pat was on a saline drip, his face as white as his pillow, his head swathed in bandages. I sat on his bed, stroking his free arm, and his eyes flickered open.

‘You angry with me?’ he asked, and I shook my head, afraid to speak.

He closed his eyes, and suddenly I knew that I could do this thing.

I could see that my performance so far had been pretty poor. I didn’t have enough patience. I spent too much time thinking about Gina and even Cyd. I hadn’t been watching Pat closely enough in the park. All that was undeniable. But I could do this thing.

Maybe it would never be perfect. Maybe I would make a mess of being a parent just as I had made a mess of being a husband.

But for the first time I saw that being a man would have nothing to do with it.

All families have their own legends and lore. In our little family, the first story that I featured in was when I was five years old and a dog knocked out all my front teeth.

I was playing with a neighbour’s Alsatian behind the row of shops where we had our flat. The dog was licking my face and I was loving it until he put his front paws on my chest to steady himself and tipped me over. I landed flat on my mouth, blood and teeth everywhere, my mother screaming.

I can just about remember the rush to hospital and being held over a basin as they fished out bits of broken teeth, my blood dripping all over the white enamel sink. But most of all I remember my old man insisting that he was staying with me as they put me out with the gas.

When the story was retold in our family, the punch line was what I did when I came home from the hospital with my broken mouth – namely stuff it with a bag of salt and vinegar crisps.

That ending appealed to my old man, the idea that his son came back from the hospital with eight bloody stumps where his front teeth used to be and was so tough that he immediately opened a packet of crisps. But in reality I wasn’t tough at all. I just liked salt and vinegar crisps. Even if I had to suck them.

I knew now that my dad wasn’t quite as tough as he would have liked to have been. Because nobody feels tough when they take their child to a hospital. The real punch line to that story was that my father had refused to leave my side.

Now I could understand how he must have felt watching his five-year-old son being put out with gas so that the doctors could remove bits of broken teeth from his gums and tongue.

He would have had that feeling of helpless terror that only the parent of a sick or injured child can understand. I knew exactly how he must have felt – like life was holding him hostage. Was it really possible that I was starting to see the world with his eyes?

He was standing outside the main entrance to the hospital, smoking one of his roll-up cigarettes. He must have been the only surviving Rizla customer in the world who didn’t smoke dope.

He looked up at me, holding his breath.

‘He’s going to be fine,’ I said.

He released a cloud of cigarette smoke.

‘It’s not – what did they call it? – a compressed fracture?’

‘It’s not fractured. They’ve given him twelve stitches and he’ll have a scar, but that’s all.’

‘That’s all?’

‘That’s all.’

‘Thank Christ for that,’ he said. He took a tug on his roll-up. ‘And how about you?’

‘Me? I’m fine, Dad.’

‘Do you need anything?’

‘A good night’s kip would be nice.’

When I was with my father, I sometimes found myself talking his language. He was the only person in the country who still referred to sleep as kip.

‘I mean, are you all right for money? Your mum told me you’re not going to take this job.’

‘I can’t. The hours are too long. I’d never be home.’ I looked across the almost empty carpark to where the night sky was streaked with light. Somewhere birds were singing. It wasn’t late any more. It was early. ‘But something will turn up.’

He took out his wallet, peeled off a few notes and handed them to me.

‘What’s this for?’ I asked.

‘Until something turns up.’

‘That’s okay. I appreciate the offer, Dad, but something really will turn up.’

‘I know it will. People always want to watch television, don’t they? I’m sure you’ll get something soon. This is for you and Pat until then.’

My dad, the media expert. All he knew about television was that these days they didn’t put on anything as funny as Fawlty Towers or Benny Hill or Morecambe and Wise. Still, I took the notes he offered me.

There was a time when taking money from him would have made me angry – angry at myself for still needing him and his help at my age, and even angrier at him for always relishing his role as my saviour.

Now I could see that he was just sort of trying to show me that he was on my side.

‘I’ll pay this back,’ I said.

‘No rush,’ said my father.

Gina wanted to get on the next plane home, but I talked her out of it. Because by the time I finally reached her late the following day, getting on the next plane home didn’t matter quite so much.

She had missed those awful minutes rushing Pat to the emergency room. She had missed the endless hours drinking tea we didn’t want while waiting to learn if his tests were clear. And she had missed the day when he sat up with his head covered in bandages, clutching his light sabre, in a bed next to the little girl who had lost all her hair because of the treatment she was receiving.