Полная версия

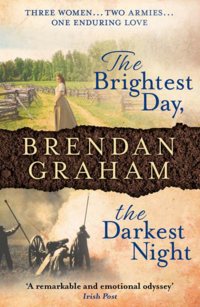

The Brightest Day, The Darkest Night

‘What book?’ Mary asked, shocked by the woman’s action and holding her mother protectively.

‘Some English filth she kept recitatin’ to herself. Ask Blind Mary – stuck sittin’ on that stoop of hers – about it. That and her niggerology! When, if Lincoln will have his way, the blacks’ll be swarmin’ all over us … and them savages no respecters o’ the likes of you neither, Sister!’ Biddy Earley added for good measure.

Mary didn’t know what to make of it all. All of her endless prayers answered and the joy, the unparalleled joy, of finding her mother alive after all these years. But yet, so dishevelled, and living in such a place.

Biddy Earley, settling a streelish curl beneath her headscarf, continued in similar vein. ‘Then looking down on the likes o’ me for going on me back to the sailors. Sure it’s no sin if it’s keeping body and soul together, is it, Sister?’ she asked boldly, uncaring of the reply. ‘No sin if you don’t enjoy it?’ she added, with a rasp of a laugh.

‘Why don’t you come with us?’ Mary asked the woman, thinking of Sister Lazarus’s words. But Biddy Earley, however hardened, was no candidate for ‘melting’ by nuns.

‘I ain’t no sinner, Sister – I don’t need no forgivin’,’ she retorted, unyieldingly. ‘Now sit quiet till t’other one comes back and then clear off out o’ here, the three o’ yis!’

Mary sat silently, offering thanks for the all-seeing hand that led herself and Louisa to this place. With her fingers, she stroked her mother’s hair, recalling the hundred brushstrokes of childhood each Sunday before Mass. As much as the dimness would allow, she studied her mother, hair all tangled and matted, its once rich lustre dulled. The fine face with that mild hauteur of bearing, now pin-tucked with want and neglect. How could her mother so terribly have fallen?

The woman’s term for Ellen – ‘widow-woman’ – what did it mean? And Ellen using her old, first-marriage name of O’Malley, as Mary had also learned from Biddy.

And Lavelle? What of Lavelle – Ellen’s husband now? Had he never found her … that time he had left the note at the convent … gone looking for her in California? The questions came tumbling one after the other through Mary’s mind.

She wished Louisa would hurry. It was all too much.

Then Ellen slept, face turned to Mary’s bosom, like a child. But it was not the secure sleep of childhood. It was fitful, erratic, full of demons. She awoke, frightened, clutching fretfully at Mary’s veil. Then, bolt upright, peered into the near dark.

‘Mary! Mary! Is that you Mary, a stor?’ Ellen said, falling into the old language.

Then, at the comforting answer, fell to weeping.

THREE

It was some hours before Louisa returned.

Ellen, startled by the commotion, awoke and feverishly embraced her. ‘Oh, my child! My dear child!’ Then she clutched the two of them to her so desperately, as though fearing imminent separation from them again.

Along with the clothing, Louisa had brought some bread and some milk. This they fed to her with their fingers, in small soggy lumps as one would an infant.

Ellen alternated between a near ecstatic state and tears, between sense and insensibility, regularly clasping them to herself.

When they had fed their mother, Mary and Louisa prepared to go, bestowing God’s blessing on Biddy for her kindness.

‘I don’t need no nun’s blessing,’ was Biddy’s response. ‘D’you think He ever looks down on me … down here in this hellhole? But the Devil takes care of his own,’ she threw after them, to send them on their way.

Out in the alleyway, they took Ellen, one on each side, arms encircling her. As they passed the old blind woman on the stoop, she called out to them. ‘Is that you, Ellie? And who’s that with you? Did the angels come at last … to stop that blasted singing?’

Ellen made them halt.

‘They did Blind Mary, they did – the angels came,’ she answered lucidly.

‘Bring them here to me till I see ’em!’ the woman ordered, with a cackle of a laugh.

They approached her.

‘Bend down close to me!’ the woman said in the same tone.

Mary first, leaned towards her and the woman felt for her face, her nose, the line of Mary’s lips.

‘She’s the spit of you, Ellie. And the hair …?’

‘What’s this? What’s this?’ the blind woman said, all agitated now as her fingers travelled higher, feeling the protective headdress on Mary’s face.

‘A nun?’ the woman exclaimed.

‘Yes!’ Mary replied. ‘I am Sister Mary.’

‘And the other one? Are you a nun too? Come here to me!’

Louisa approached her. ‘I am called Sister Veronica.’

Again the hands travelled over Louisa’s face, the crinkled fingers transmitting its contents to behind the blindness.

Louisa saw the old woman’s face furrow, felt the fingers retrace, as if the message had been broken.

‘Faith, if she’s one of yours, Ellie, then the Pope’s a nigger,’ Blind Mary declared with her wicked laugh.

Louisa flinched momentarily.

The old woman carried on talking, her head nodding vigorously all the while, but with no particular emphasis. ‘I’m supposin’ too, Ellie – that you never was a widow-woman neither?’

‘No, I wasn’t – and I’m sorry …’ Ellen began.

The woman interrupted her, excitedly shaking her stick. ‘I knew it! I knew it! Too good to be true! Too good to be true! That’s what my Dan said afore he left to jine the cavalry … for the war,’ she explained, still nodding, as if in disagreement with herself … or her Dan. ‘ What was you hiding from, down here, Ellie?’ she then asked.

This time however, Ellen made no answer.

It was a question that resounded time and again in Mary and Louisa’s minds, as they struggled homewards. Out under the arch they went, drawing away from Half Moon Place, the old woman’s cries, like the stench, following them.

‘The Irish is a perishing class that’s what!’ Blind Mary shouted after them. ‘A perishing class … and my poor Dan gone to fight for Lincoln and his niggerology. This war’ll be the death of us all.’

FOUR

By the time they had reached the door of the convent, Louisa and Mary were in a perfect quandary.

They could not reveal Ellen’s true identity, lest they all be banished. Acceptance into the convent as a novice implied a background and family beyond blemish. There could be no whiff of scandal attached to those who were to be Brides of Christ.

It would be held that they had known all along of their mother’s fallen state and engaged in the concealment of it.

‘It was not a deceit then but it is a deceit now,’ Mary said to Louisa, ‘to continue not to reveal her identity … whatever the consequence.’

‘It is a greater good not to reveal her,’ Louisa argued. ‘Mother is in dire need of corporeal salvation, if not indeed of spiritual salvation!’

‘That is the end justifying wrongful means,’ Mary argued back, torn between her natural instinct to follow Louisa’s reasoning, and the more empirical precepts of religious life.

‘We have been led to her for a purpose,’ Louisa countered. ‘It would not be natural justice to have her now thrown back on the streets. Natural justice supersedes the laws of the Church.’

Mary prayed for guidance. ‘Lord not my will, but Thine be done.’ Having passed the question of justice to that of a higher jurisdiction, Mary was somewhat more at ease with Louisa’s plan.

‘I don’t think “Rise-from-the-Dead” will recognise the likeness between you and Mother.’ Louisa gave voice to Mary’s own fear.

Mary looked at her mother’s sunken state. Sister Lazarus would have seen her only the once … and that many years ago. Still, little passed unnoticed with ‘Rise-from-the-Dead’.

They both impressed upon Ellen the importance of not revealing herself. She was a Penitent, rescued from the streets. Nothing more.

‘That I am,’ she echoed.

Sister Lazarus received them full of concern.

‘Oh, the poor wretch! Divine Providence! Divine Providence that you rescued her, from God knows what fate!’

Mary’s heart beat the easier as the older nun bustled them in without any hint of recognition.

‘A nice hot tub, then put her to bed in the Penitents’ Infirmary,’ Sister Lazarus directed. ‘You, Sisters, take turn to sit with her, lest she take fright at her unfamiliar surroundings.’

They stripped her then, Louisa supporting her in the tub, while Mary sponged from her mother’s body the caked history of Half Moon Place, both of them joyful beyond words at having been her salvation. She, who through famine and pestilence, had long been theirs.

When Louisa spoke, Ellen would turn to look at her, face spread wide in amazement. ‘I know, Mother,’ Louisa said. ‘I was “the silent girl”. All those years when you tried to get me to speak, I would not. Like your story, it is for another day.’

Ellen then turned her head from one to the other of her children, eyes brimming with delight, as if the angels of the Lord had come down from on high and tended her.

Shakily then, she pressed the thumb and forefinger of her right hand to her lips and leaned, first to Mary’s forehead, then to Louisa’s, crossing them in blessing, as she had done, down all the day-long years of childhood.

FIVE

Ellen slept in the Penitents’ Dormitory. About her were raised the fitful cries of other Penitents rescued from the jaws of death or, as the Sisters saw it, from a fate far worse – the jaws of Hell. For here were common nightwalkers, bedizened with sin; others sorely under the influence of the bewitching cup. Still others snatched from grace by the manifold snares of the world, the flesh and the devil. These, if truly penitent, the Sisters sought to reclaim to a life of devotion. But for now these tortured souls struggled. Redemption was not for everyone.

Penitents, those who desired it, could be regenerated. Eventually, shed of all worldly folly, their former names would be replaced by those of the saints. These restored Penitents would then be released back to secular society.

Some Penitents, drawn either by love of God, or fear of the Devil, remained, took vows, becoming Contemplatives. Continuing to lead lives of prayer and penance within the community of the Sisters.

Her own sleep no less turbulent than those around her, Ellen’s mind roved without bent or boundary. Before her, on a pale and dappled horse, paraded Lavelle. Loyal, handsome Lavelle, all gallant and smiling.

Smiling, as on the day she, with Patrick, Louisa and Mary in tow, had docked at the Long Wharf of Boston. Lavelle, with his golden hair, waiting in the sun, waving to them amid the baubled and bustling hordes on the shore. Patrick, curious about this stranger who would replace his father. Their mother’s ‘fancy man’ in America, as Patrick called Lavelle.

In the dream she saw herself laughing, this time at her doorway, talking with Lavelle. He asking a question, she saying ‘yes’ and then him high-kicking it, whistling through that first Christmas snow, down the street merrily. Then springtime … the wedding … she, taking ‘Lavelle’ for a name, relinquishing her dead husband’s name of O’Malley.

Out of the past then a nemesis – Stephen Joyce – who had delivered her first husband Michael to that early death.

Her dream changed colours then. Gone was the brightness of sun and snow … of music on merry streets. Now appeared a purpled bed. On it Stephen Joyce, book in hand reading to her. She, naked at the window, her body turned away from him. Singing to the darkly-plummed world outside … the night pulping against the window, its purple fruit oozing through the windowpane, over her body … staining her. Abruptly again, her dream had changed course. Now Stephen – dark, dangerous Stephen – he, too astride a horse, a coal-black horse, sword in hand and beckoning her. And Patrick – her dear child, Patrick – what was Patrick doing here? Giving her something … but beyond her reach. Mary and Louisa, white-winged, holding her back from going to him. Lavelle again, this time madly galloping towards them on the pale horse. Them cowering from its flashing hooves.

Frightened, she bolted upright in the bed, Louisa at her side restraining her, soothing her anxiety.

‘There, Mother, there – it’s just a bad dream, I’m with you now,’ Louisa said tenderly.

Fearfully, Ellen embraced her, afraid her adopted daughter might disappear back into the frightening dreamworld.

Louisa held her mother, until sleep finally took Ellen.

Through the New England winter began the long, slow restoration. First the temporal needs of the body. Not a surfeit of food but ‘little and often’ as Sister Lazarus advised, ‘and a decent dollop of buttermilk daily, combined with fruit – and young carrots’, for the recovery of Ellen’s eyes. ‘Common luxuries, which no doubt have not passed this poor soul’s lips since Our Saviour was a boy,’ Sister Lazarus opined.

Mary trimmed the long mane of Ellen’s hair, removing the frayed ends and straightening the raggle-taggle of knots that had accumulated there. Gradually, the pallor evaporated from Ellen’s face, a hint of rose-pink returning to her lips. Under the Sisters’ care, the physical contours of Ellen’s body began somewhat to re-establish themselves. It was not long before Louisa and Mary could both begin to see their mother re-emerge, as they had once remembered her.

‘It is the buttermilk,’ Lazarus was convinced, thankfully still showing no signs of recognition.

With Mary and Louisa’s help Ellen could now go to the Oratory for prayer and reflection. There they would leave her a while, to ponder alone. Never once did they ask about her missing years. She was grateful for that … was not yet ready to tell them. But that day would come. Perhaps early in the New Year.

Before Christmas, when she was stronger, and at Sister Lazarus’s insistence that ‘God and Reverend Mother will provide,’ Mary and Louisa took Ellen to an oculist. Years of making the Singer machines sing for Boston’s shoe bosses, had taken its toll on their mother’s eyes.

Dr Thackeray, a kindly, intent man – a Quaker, Ellen had decided, without knowing why – held his hand up at a distance from her, asking her to identify how many digits he had raised. Depending on her answer, he moved either further away or closer to her. At the end of it all he disappeared, returning at length with a stout brown bottle which he declared to contain ‘a soothing concoction’.

‘This to be poulticed on both eyes for a month of days; to be changed daily – only in darkness,’ he instructed. ‘Even then both eyes must remain fully shuttered.’ She would, he said, ‘see no human form until mine, when you return.’

He gave no indication of what improvement, if any, he expected after all of this.

During her month of darkness, Ellen’s general state of health continued to incline. She grew steadily stronger, the tone of her skin regained some former suppleness, and from Mary’s constant brushing, the once-fine texture of her hair had at last begun to return.

‘It is as much the nourishing joy at your presence, as anything Sister Lazarus’s buttermilk and young carrots might do,’ she said with delight to Mary and Louisa.

Ellen was thankful of Dr Thackeray’s poultice. That she would not have to fully face them when, at last, she told her daughters the truth; not have to look into their eyes, they into hers.

Blindness she had long been smitten with, before ever she had put first stitch into leather.

Stephen Joyce, who had ignited such debasing passions in her, was not to blame. Nor Lavelle … least of all, her ever-constant Lavelle. The blindness was solely hers – her own corroding influence on herself.

She worried about her dream and its recurrence – that by now she should have exorcised all the old devils about Stephen. Why had he appeared so threatening – sword aloft? Why the black horse and Lavelle the pale one? Good and Evil – and had they at last met? And Patrick – she unable to reach him?

Stephen first had appeared in her life in 1847. There were troubled times in Ireland – blight, starvation, evictions. Like a wraith he had come out of the night to meet with her husband Michael.

She had not interfered as rebellious plots against landlords were hatched but she had sensed tragedy. This dark man who could excite the hearts of other men to follow him, would she knew, one day bring grief under her cabin roof. And so it was. Not a moon had waned before her husband Michael, her beautiful Michael, lay stretched in the receiving clay of Crucán na bPáiste – the burial place high above the Maamtrasna Valley.

Evicted then, during the worst of the famine, and in desperation to save her starving children, she had been forced to enter a devilish pact. Her allegiance to the Big House was bought, her children given shelter. The price – her forced emigration from Ireland – and separation from them. Patrick aged ten years, Mary a mere eight. It was Stephen Joyce, the peasant agitator, scourge of the landlord class, who had come to her to guarantee their safety. Whilst she had blamed him for Michael’s death, she had, for the sake of her children, no choice but to accept his offer. Eventually, she had returned to reclaim them.

Now years later, here in America, her children had reclaimed her.

SIX

‘Sit still, Mother!’ Mary chided, as she unfettered Ellen’s eyes.

‘Mary … I have something …’ Ellen began, wanting at last to tell her.

Mary, remembering the tone her mother adopted when she had something to say to them, knew it was pointless resisting. She put the used poultices on the small table, fixed her attention on Ellen’s closed eyelids … and waited.

‘I … I have … something to confess to you … a grave wrong,’ Ellen began, falteringly.

‘Have you confessed it to God?’ Mary asked, simply.

‘Yes, Mary … many times … but, in His wisdom, He has directed that you and Louisa should find me – so that I should also confess it to you.’

Mary took her mother’s hands, bringing Ellen close to her. ‘If God has forgiven you, Mother, then who am I not to?’

‘I still must tell you, Mary,’ Ellen said, more steadily.

Faces now inclined towards each other, mother and child, priest and penitent, Ellen began. ‘I committed … the sin of Mary Magdalen … with … Stephen Joyce,’ she said quietly, her long hair forward about her face, shrouding their hands.

Mary uttered no word. Remained waiting, still holding her mother’s hands. Ellen, before she continued, opened her eyes and peered into Mary’s. Into her own eyes, it seemed.

‘I betrayed you all: Lavelle, a good man and a good husband; you, my dear child; Patrick … Louisa.’ Then, remembering Mary’s father, Michael: ‘Even those who have gone before!’

Ellen knew how the words now struggling out of her mouth would be at odds with everything for which Mary had held her always in such loving regard. She trembled, awaiting her child’s response.

‘Mother, you must keep your eyes closed … until it is time,’ Mary said, without pause, putting a finger to her mother’s eyes, blessing her darkness, protecting her from the world.

Mary then fell to anointing the fresh coverlets for Ellen’s eyes. She said nothing more while completing the dressing. Then, Mary left the room.

When she returned she pressed a set of rosary beads into Ellen’s hands.

‘One of the Sisters sculpted these from an old white oak,’ Mary explained. ‘Louisa and I were saving them for you until the bandages came off … but …’ She didn’t finish the sentence, starting instead a new one … ‘We’ll offer up the Rosary – the Five Sorrowful Mysteries.’

Ellen, in reply, said nothing until between them then, they exchanged the Five Mysteries of Christ’s Passion and Death.

The Agony in the Garden …

The Scourging at the Pillar …

The Crowning with Thorns …

The Carrying of the Cross …

The Crucifixion.

Passing over and back the Our Fathers …

‘… forgive us our trespasses … as we forgive those who trespass against us.’

And the Hail Marys, ‘… pray for us sinners …’ the words taking on the mantle of a continued conversation.

Like a shielding presence between them, Ellen counted out the freshly-hewn beads, reflecting upon the Fruits of the Mysteries – contrition for sin; mortification of the senses; death to the self.

Afterwards, in unison, they recited the Salve Regina. ‘To thee do we fly poor banished children of Eve, To thee do we send up our sighs, mourning and weeping … and after this, our exile … O clement, O loving, O sweet Virgin Mary! Pray for us … that we may be made worthy …’

When it was done they sat there, unspeaking. Ellen, the great weight partly uplifted from her; Mary, unfaltering in compassion at the enormity of what had passed between them.

‘I will tell Louisa myself, Mary,’ Ellen said. ‘Then I must find Patrick … and Lavelle.’

The younger woman stood up, made to go and stopped. Turning, she embraced the shoulders of the other woman, pulling her mother towards her, the fine head within her arms. Gently, she stroked the renewed folds of Ellen’s hair. As a mother would a damaged child.

SEVEN

The following evening Louisa came.

With mounting trepidation, Ellen heard the flap of Louisa’s habit, the whoosh of air that preceded her adopted daughter. Everything but flesh of flesh, Louisa was to her. How frightened the child must have been all those years to have so stoically maintained her silence. That, if she had spoken, she would again have been shunned. Left to the roads and the hungry grass.

Ellen awaited her moment and when Louisa had removed the poultices, caught her by the wrists.

‘Sit for a moment, Louisa!’

Slowly, agonisingly, Ellen fumbled for the words with which to tell Louisa. Almost as soon as she had begun, Louisa stopped her, putting a hand to Ellen’s lips.

‘Mother, dearest Mother, you needn’t suffer this … I already know,’ she said, causing Ellen to startle. ‘I suppose I’ve always known,’ Louisa continued. ‘You almost told me once … in word and look. That last time I played for you … the Bach … the loss of Heaven in your face …’ She paused. ‘… and then, the book.’

‘Oh, my dear Louisa … you never …’ Ellen began.

‘No, I never said anything.’ Louisa answered the unfinished question. She gave a little laugh. ‘In my silent state I didn’t have to!’

‘You never condemned me?’ Ellen asked.

‘Condemn you, Mother? You who saved me from certain death? Who loved me as her own?’ Louisa held her tightly. ‘Condemn you?’ she repeated. ‘I thank God every waking moment that He at last restored you to us.’

The Vespers bell tolled, calling the Sisters to evening prayer. Still embracing, Ellen and Louisa fell silent, each making her own prayer … for the other.

Ellen explained what she still must do regarding Patrick and Lavelle.

‘You must do as conscience directs,’ Louisa answered.

‘It would be my dearest wish to first remain here a while, with you and Mary,’ Ellen replied.

The prayer bell stopped. Louisa waited a moment for Ellen to continue.

‘What restrains me is that by remaining, it may reveal me and so force you and Mary to finish your work here. So, I have decided to take my leave quietly and avoid that possibility.’

‘How will you live, what will sustain you?’ Louisa worried.

‘The Lord will sustain me – as He has up to now.’

Next afternoon Sister Lazarus came to visit Ellen. She could not see how closely the nun studied her, as she complimented Ellen on her wellbeing. ‘Doing nicely, are we? Doing nicely! Thanks be to God and His Holy Mother.’

The following day Sister Lazarus again visited her, this time with Louisa and Mary in tow.