Полная версия

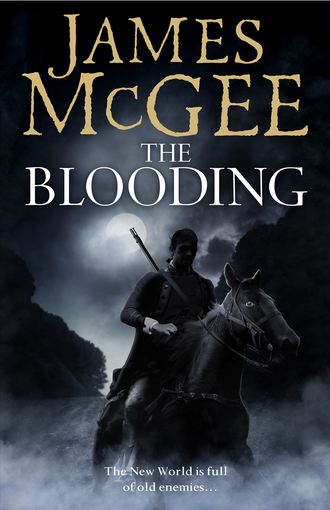

The Blooding

The strike had been taught to him by Chen, an exiled Shaolin priest Hawkwood had met in London. They sparred together in a cellar beneath the Rope and Anchor public house. Chen had cautioned that, if delivered too robustly, there was a danger such a blow could kill. He had then proceeded to demonstrate the precise speed at which the strike had to be delivered in order to subdue rather than maim or kill, by using the technique against Hawkwood. After being laid out half a dozen times, Hawkwood had got the idea. As the unfortunate Captain Curtiss had discovered to his cost, Chen’s former pupil had learned his lesson well.

Suitably attired, Hawkwood was on the ferry by the time the captain stumbled out of the alleyway. The three hundred yard crossing proved uneventful, though the numbing wind that eddied downriver from the northern reaches offered a prophecy of wintry conditions ahead. In the darkness it was difficult to make out the far bank; the high bluffs that dominated the eastern shore cast dark shadows over the Greenbush waterfront. All that could be seen were the lights from the rag-tag collection of houses huddled behind the landing stage, which seemed to be drawing the ferry like a moth to a candle flame.

The vessel – if the flat-bottomed, punt-shaped barge could be called such a thing – was not overladen. There were only half a dozen passengers, all male. Three were in uniform, presumably heading back to barracks after a night out. The others could have been military men in civilian dress or Greenbush residents; Hawkwood had no way of knowing. One of the uniformed men had been drinking heavily, or at least beyond his capacity. He spent the short voyage voiding over the ferry’s gunwale, his retching almost matching in volume the wash of water against the hull and the rasp of the ropes as they were hauled through the pulley rings.

Hawkwood was glad of the distraction this provided, for he’d no wish to engage his fellow passengers in conversation. Even the most cursory enquiries would inevitably reveal his ignorance of both his regiment and the cantonment to which he was heading. And the less opportunity anyone had to study and memorize his features, the better. He had, therefore, affected a show of distaste for the vomiting and removed himself from his fellow passengers, gazing out over the rail while immersing himself in the darkness of the night and thoughts of what his next move might be.

It was a fact of war that even the best-laid plans had a tendency to fall apart upon first contact with the enemy. On hostile ground, with limited access to resources, Hawkwood had no alternative but to improvise. And time was running out.

The cantonment lay at the end of a well-trodden dirt road that rose in a steady incline stretching a mile and a half from the landing stage. Hawkwood knew the way. He’d made a dry run that afternoon. Had he not had the benefit of studying the lie of the land in daylight he would have found it impossible to find his way now, with the trees creating deep dense shadows across the path.

Hoisting his knapsack on to his shoulder, he increased his stride and forged up the trail. He kept up the pace for several minutes before halting. His long coat rendering him almost invisible in the blackness, he listened for the other ferry passengers; long seconds passed before his ears picked up the sounds of slow stumbling progress further down the hill. No threat there; he moved on.

Soon the ground began to level off and the trees started to give way. Lights that had hitherto been the size of fireflies grew into patches of candle-glow spilling from windows and from lanterns as the cantonment appeared before him.

The camp was large, probably close to two hundred acres. Even in daylight it had been difficult to determine the exact boundaries, for there were no perimeter walls or fences separating the place from the outside world. Hawkwood could not determine whether this was a monumental dereliction of security or because the army deemed it impractical or unnecessary.

From what he’d seen during his afternoon sortie, the buildings were in good condition. Quade had told him that work on the site had only commenced in March, with the last of the barracks erected in September. Hawkwood doubted the paintwork would look so pristine after the winter snows and the spring thaw had wreaked their havoc.

Courtesy of Major Quade, he also knew that the cantonment could accommodate four to five thousand troops, close to three-quarters of the total complement of the American regular army. As a divisional headquarters, it boasted impressive facilities: living quarters for soldiers and officers of field rank and below: stables; a smithy; a powder magazine, armoury and arsenal; a multitude of storage areas and essential workshops; a guardhouse; and a hospital. The dominant feature, however, was the parade ground. It straddled the centre of the camp and was bordered by soldiers’ barracks – four blocks on either side – and by officers’ quarters at either end. The accommodation wings had been easy to identify by the manner in which the soldiers entered and exited the buildings. Not that there appeared to be that many personnel about, which confirmed Quade’s account of General Dearborn having transferred the bulk of his command to Plattsburg. That might also explain why precautions appeared to be so lax.

As part of his reconnaissance, Hawkwood had scanned the approach roads for sentry posts, but like the perimeter safeguards they’d been conspicuous by their absence. Even now, there appeared to be no piquets on duty at the access points. Could the Americans really be that complacent? Were they so confident in their might and their independence that they assumed no one would dare breach their unguarded perimeter? Well, he was about to prove them wrong.

Opening his greatcoat buttons so as to reveal a glimpse of the tunic beneath, he drew himself up, adjusted his hat, and strode confidently into the lions’ den.

It had been a few years since Hawkwood had last set foot in an army compound, but even if he’d been delivered into the cantonment blindfolded and in pitch-dark, he would have found his bearings almost immediately. Military camps the world over had an odour and an atmosphere all of their own. And so it was with Greenbush.

Hawkwood’s objective was the cantonment’s southern corner. He’d already marked the site of the stables but they would have been easy to find by sense of smell alone. The combination of horse piss, shit, leather and straw was unmistakable. The three blocks of stalls formed a U-shape around a yard, with a farrier’s hut positioned in the centre. Illuminated by lanterns hanging alongside the stable doors, the place looked to be deserted. It couldn’t be that easy, surely?

It wasn’t.

Someone laughed, the sound abrasive in the quiet of the evening. Hawkwood paused, looking for the source, and saw a faint beam of light leaking from a door at the end of the left-hand stable block. As he moved towards it, his ears caught the low murmur of voices and another dry, throaty chuckle. The exchange was followed by a rattling sound, as though several small pebbles were being rolled around the inside of a hollow log.

He paused, aware there were two choices now open to him. The first was to continue by stealth alone in the hope that he could achieve his objective without being discovered, which was unrealistic. The second carried an equal amount of risk, but was more overt and would involve a lot more nerve. If he could pull it off, though, he’d undoubtedly save time.

He decided to go with the second option.

Placing his knapsack against the wall, he took a deep breath and pushed open the door.

Three men, coarse-faced and lank-haired, dressed in unbuttoned tunics, were seated at a rough table surrounded by walls festooned with tack. A small pile of coins and a tin mug sat by each man’s elbow. In the centre of the table a half-empty bottle of rye whiskey stood next to a lantern and a wooden platter containing a hunk of bread, some sliced ham and a wedge of pale yellow cheese with a small knife stuck in the centre of it.

One of the men was holding a wooden cup. He gave it a shake as Hawkwood walked in; the resulting rattle was the sound that had been audible from the yard. Not pebbles in a log but wooden dice. The dice man’s hand stilled and three sets of eyes registered their shock and surprise. Clearly, evening inspection by a ranking officer was not a regular occurrence.

“Good evening, gentlemen.”

Hawkwood fixed his attention on the man holding the dice. He waited two seconds, then demanded brusquely: “Your name – remind me.”

The dice man scrambled upright. “Corporal J-Jeffard, sir.” His gaze flickered nervously to the collar and top half of the tunic, made visible by Hawkwood’s unbuttoned greatcoat.

“Ah, yes,” Hawkwood said, injecting sufficient disdain into his voice to inform everyone in the room who was in charge. “Of course. Labouring hard, I see.”

The corporal reddened. His Adam’s apple bobbed. Hawkwood swung towards the other two, both of whom had also risen to their feet. One of them was trying to fasten his collar at the same time. Recognizing a losing battle, he gave up. Whereupon, reasoning that it might be better if he assumed at least some sort of military pose, he dropped his hands to his sides. His companion followed suit. The movement tipped his chair on to its back. All three men flinched at the clatter.

Hawkwood could smell the alcohol on their breath. “And you are …?” he enquired.

“Private Van Bosen, sir.”

“Private Rivers, Captain.”

Hawkwood viewed the bottle and the mugs. “Care to explain, Corporal?”

Jeffard flicked a nervous glance towards his companions.

“Don’t look at them!” Hawkwood snapped. “Look at me!”

The trooper swallowed and found his voice. “Taking a break between duties, Captain. We were about to return to our posts when you arrived.”

“Of course you were,” Hawkwood said witheringly. “Nice try. Shame you’ve been rumbled. If I were you, I’d practise those excuses. You can put down the dice; I’ve a job for you.”

He paused, watching as a chastened Jeffard did as he was told, allowing the silence to stretch to breaking point before adding, “I’m here because I have urgent dispatches for both General Dearborn and Colonel Pike. I need two good mounts, saddled, fully equipped and ready to depart in ten minutes. Manage it quicker than that and you can finish your game.” He turned to the others. “Anyone else on duty here, or is this it?”

A flustered nod from Van Bosen. “No, sir. I mean, yes, sir. Just us, sir.”

Hawkwood vented a silent sigh of relief as he waved his hand dismissively. “Yes, well, whichever it is, I don’t care, frankly. Only, with the three of you, it won’t take long, will it? Ten minutes, gentlemen. I’ll expect those damned animals to be ready or I’ll want to know why. Don’t make me put the three of you on a charge. That happens and you’ll be shovelling shit till doomsday.”

Giving them no chance to respond, Hawkwood turned on his heel and stalked out of the room.

As soon as he was outside and out of sight, he moved swiftly towards the shadows cast by the farrier’s hut. Tucking himself against the wall, he waited. A few seconds later, he watched as the three troopers left the tack room and hurried towards the adjacent stable block. The moment they disappeared inside, Hawkwood, his movement concealed by the intervening hut, crossed to the stable block on the opposite side of the yard. Grabbing a lantern from the wall, he hauled back the door. He was immediately assailed by the pungent aroma of hay, horse sweat and fresh droppings.

The stalls were set out along both sides of a central aisle. Beyond the reach of the lantern glow, dark forms stirred restlessly in the shadows. Straw rustled. A soft whickering sound eddied around the walls as the stable’s occupants caught his scent. He moved down the aisle, treading carefully. He had no desire to panic the animals. At least not yet.

As he looked for an empty stall, he prayed that Jeffard and his cronies were as inefficient as they had appeared to be. With luck, the brew they’d been drinking would slow them down long enough to allow him the valuable seconds he needed.

Two stalls had been left vacant. Hawkwood picked the one furthest from the door and looked for a supply of dry straw. Bales of it were stacked in a storage area at the end of the aisle. Laying aside the lantern and working quickly, he broke open one of the bales, gathered the contents in his arms and piled the bulk of it loosely against the slatted walls of the empty stall, trailing the rest out into the aisle.

Then he set it alight.

He used the lantern. He’d been planning to use the stolen flint and steel to start the fire, but they weren’t needed. The accelerants had been provided for him. He watched anxiously as the first tentative flames scurried along the dry stalks. When he was confident the fire had taken hold, he tossed the lantern to one side and backed away, unlatching the doors to the stalls as he went. By the time he reached the main door, the first of the horses was already stamping the ground and snorting nervously.

Exiting the stable, Hawkwood propped the outer door open as far as it would go and retraced his steps to the farrier’s hut. He made it to the tack room just as Corporal Jeffard led the first of the saddled horses into the yard.

Hawkwood counted to five and strode arrogantly into view. His sudden appearance had the desired effect: the troopers started in surprise. The less time they had to think, the less likely they would be to question his orders or, more inconveniently, his identity. Hawkwood wanted them on tenterhooks as to what this supercilious bastard of an officer would do next. From their expressions, the ruse appeared to be working.

“Well done, Corporal,” Hawkwood drawled. “There’s hope for you yet.”

The corporal drew himself up. “They’re sound, Captain. They ain’t been out for a day or two, so they’ll be glad of the exercise.”

Then they won’t be disappointed, Hawkwood thought, running a critical gaze over the animals. “All right, gentlemen. You’ve redeemed yourselves. You may return to your, ah … duties.”

A grin of relief spread across the corporal’s face. “Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.”

At that moment Private Van Bosen lifted his gaze to a point beyond Hawkwood’s shoulder and gasped hoarsely, “Oh, Christ!”

The exclamation was accompanied by the unmistakable clatter of hooves coming from the other side of the farrier’s hut.

Hawkwood, Corporal Jeffard and Private Rivers spun round in time to see a dark mass of stampeding horses careering noisily towards the open end of the stable yard and the darkness beyond.

“Jesus!” Jeffard stared in horror and disbelief at the vanishing animals.

Hawkwood frowned. “I smell smoke.”

“Bloody stable’s on fire!” Rivers yelped as the realization hit him.

Turning to Jeffard, who was holding the reins of the two saddled horses, Hawkwood barked, “Wait here! Don’t let them go! You two, with me! Move!”

The blaze had spread quicker than he had anticipated. The interior of the stable looked to be well alight, though the fire had yet to reach the roof. From inside, the fizzle of burning straw and the splintering of timber could be plainly heard. It wouldn’t be long before flames were dancing around the open door. Smoke was starting to pour through the gaps in the shingles, further darkening the already overcast night sky.

Hawkwood pushed Van Bosen towards the fire. “Don’t just stand there, man! Get buckets! We can save it! You, too, Rivers! I’ll go for help!”

Leaving them, Hawkwood ran back to where Corporal Jeffard was struggling to hang on to the two mounts. Both were now straining at the reins, having picked up the smell of the fire, and the scent of fear from their fleeing stable mates.

“Give them to me!” Hawkwood stuck out his hand. “Fetch water! I’ll alert the camp! If it spreads to the other blocks, we’re done for! Go!”

Jeffard, mouth agape, passed the reins over.

“Go!” Hawkwood urged. “Go!”

Jeffard turned tail and ran. Pausing only to snatch up his knapsack, Hawkwood climbed on to the first horse. Coiling the reins of the second in his fist, he dug in his heels and spurred the frightened animals out of the yard. As he did so, he saw from the corner of his eye two figures running frantically with buckets towards the smouldering building.

When he was clear, Hawkwood looked back. There were no flames to be seen as yet, but it could only be a matter of time before they became visible. It was doubtful the corporal and his friends would be able to cope on their own. Soon, they’d have to decide whether to carry on trying to save the stable block, or let it burn while they led the remaining horses to safety. From what Quade had told him about the chronic shortage of horseflesh available to the American army, they’d be anxious to preserve at all costs the few they did have.

Either way, they had enough to keep them busy for the moment.

Leaving the scene of impending chaos behind him, he urged the horses up the trail and into the trees. It was darker in among the pines and the last thing he wanted was for the animals to stumble, but he was committed now so he prayed that animals accustomed to carrying dispatches at the gallop would be agile enough not to lose their footing on the uneven slope.

Keeping to the higher ground, he could just make out the rectangular shape of the soldiers’ barracks below him and the latrine blocks attached to each one. Lights showed dimly behind shuttered windows. From what he could see, most of the garrison was slumbering, oblivious to the drama unfolding at the other end of the camp.

A break appeared in the path. Hawkwood paused and took his bearings before dismounting. The last of the barrack blocks was now in sight. At any moment Corporal Jeffard and the two privates would tire of wondering why no help had arrived and decide to sound the alarm for themselves. When that happened, all hell would surely break loose. Tethering the horses to a tree, he made his way down the slope using the woods as cover.

The camp guardhouse lay at the north-eastern corner of the cantonment at the end of a short path linking it to the parade ground. Two-storeys high and built of brick and stone, its entrance was protected by a wooden porch.

And an armed sentry.

Hawkwood waited until the sentry’s back was turned before emerging from the trees at a leisurely pace. He was twenty yards away from the building when the challenge came.

“Halt!” The sentry stepped forward, musket held defensively across his chest. “Who goes there?”

Hawkwood kept walking. “Captain Hooper, with orders from the colonel. Stand down, Private. You’ve done your job.” Hawkwood hardened his gaze, letting it linger on the sentry’s face. “Who’s the duty sergeant?”

Recognizing the uniform and disconcerted by the clipped authority in Hawkwood’s voice, the sentry hesitated then stood to attention. “That’ll be Sergeant Dunbar, sir.”

“And is he awake?” Hawkwood forged a knowing smile to give the impression that he and Dunbar were old comrades.

“Yes, sir.” The sentry relaxed, allowing himself a small curve of the lip.

“Glad to hear it.” Hawkwood raised a dismissive hand. “Don’t worry. I’ll find him. Carry on.”

“Sir.” Flattered at having been invited to share a joke with an officer, the sentry shouldered arms and resumed his stance.

Hawkwood let out his breath.

Not far now.

It didn’t matter which army you fought for, guardhouses were always cold, cheerless places, built for purpose and furnished with only the most basic of amenities. So Hawkwood knew what he was going to see even before he passed through the door. There’d be a duty desk, above which would be affixed a list of regulations and the orders of the day; an arms rack; a table and a couple of benches; probably a trestle bed or two; a stove and, maybe, if the occupants were sensible and self-sufficient enough, a simmering pot of over-brewed coffee and a supply of tin mugs.

He wasn’t disappointed. The only items he hadn’t allowed for were the four leather buckets lined up along the wall just inside the door; fire-fighting for the use of, as the inventory might well have described them.

Four buckets aren’t going to be nearly enough, was Hawkwood’s passing thought as he turned his attention to the man behind the desk, who was already rising to his feet at the unexpected and probably unwelcome arrival of an officer.

“Sergeant Dunbar,” Hawkwood said, making it a statement, not a question. “Just the man.”

Always pander to the sergeants. They’re the ones who run the army. It’s never the bloody officers.

The sergeant frowned. “Captain?” he said guardedly.

Hawkwood didn’t bother to reply, but allowed his gaze to pass arrogantly over the other two men in the room, both of whom were in uniform, muskets slung over their shoulders. Relief sentries, presumably, either just returning from their circuit or about to begin their rounds. They straightened in anticipation of being addressed, but Hawkwood merely viewed them coldly in the time-honoured manner of an officer acknowledging the lower ranks; which is to say that, aside from noting their existence, he paid them no attention whatsoever. Neither man appeared insulted by the slight. If anything, they seemed relieved. Let the sergeant deal with the bastard, in other words.

“Everything in order here?” Hawkwood enquired.

The sergeant continued to look wary. “Yes, sir. All quiet.”

“Good. I’m here on the colonel’s orders: I need information on the prisoners that were transported from Deerfield earlier today.”

Caution flickered in the sergeant’s eyes. “Yes, sir.” Turning to his desk and the ledger that lay open upon it, he rotated the book so that Hawkwood could view the cramped script. “Names entered as soon as they arrived, Captain. Eleven, all told; one officer; ten other ranks.”

“Very good.”

Hawkwood ran his eyes down the list. His heart skipped a beat when he saw the name he was looking for. Keeping his expression neutral, he scanned past the name to the prisoner’s rank and regiment and place of capture: major, 40th Regiment, Oswegatchie.

“Is there a problem, sir?” The sergeant frowned.

Hawkwood recognized the defensive note in Dunbar’s query. Like guardhouses, duty sergeants were the same the world over: convinced that nothing ran smoothly without their say so and that even the smallest hint of criticism was a direct insult to their rank and responsibility. The other truth about sergeants was that every single one of them worth his salt had the knack of injecting precisely the right amount of scepticism into his voice to imply that any officer unwise enough to suggest there might be the cause for concern was talking out of his arse.

“Not at all, Sergeant. Everything’s as I’d expected. Nice to see someone’s keeping a tight rein on things around here.”

Hawkwood allowed the sergeant a moment to preen, then assumed a pensive look. He let his attention drift towards the two privates.

The sergeant waited expectantly.

Hawkwood returned his gaze to the ledger and pursed his lips. “We’ve received intelligence suggesting there may be an attempt to free the prisoners.”

The sergeant’s eyebrows took instant flight. “From what quarter, sir?”

Hawkwood didn’t look up but continued to stare ruminatively at the ledger while running his finger along the list of names.

“That’s the problem: we’re not sure. My guess is it’s some damned Federalist faction that’s refused to lie down. Or the Vermonters. This close to the border, it’s certain they’ve been keeping their eyes open and passing on information to their friends in Quebec.”

Hawkwood was relying on information he’d siphoned from Major Quade; support for the war was far from universal among those who depended for their livelihood on maritime trade and cross-border commerce with the Canadian provinces.