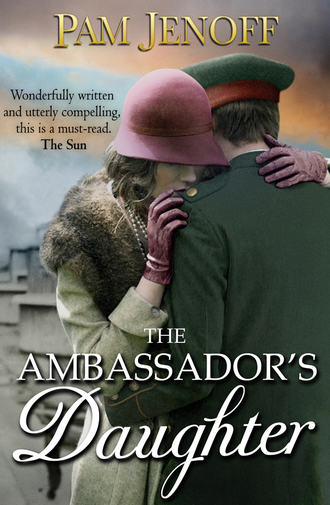

The Ambassador's Daughter

Полная версия

The Ambassador's Daughter

Жанр: исторические любовные романыисторическая литературасовременная зарубежная литературасерьезное чтениеоб истории серьезно

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2018

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу