Полная версия

Saving Danny

‘I’ll talk to your mother about George when I see her tomorrow at school,’ I said to Danny.

‘Need George,’ Danny said despondently with his head down. I felt so sorry for him.

‘I understand,’ I said. ‘We’ll see what your mother says tomorrow.’

This was the best I could offer and it seemed to reassure Danny a little, for he climbed off the sofa and went over to the games and puzzles that were still laid out on the floor. Kneeling down, he began to play with the Lego. I was pleased; this was a good sign. When a child feels relaxed enough to play it shows they are less anxious and starting to settle in.

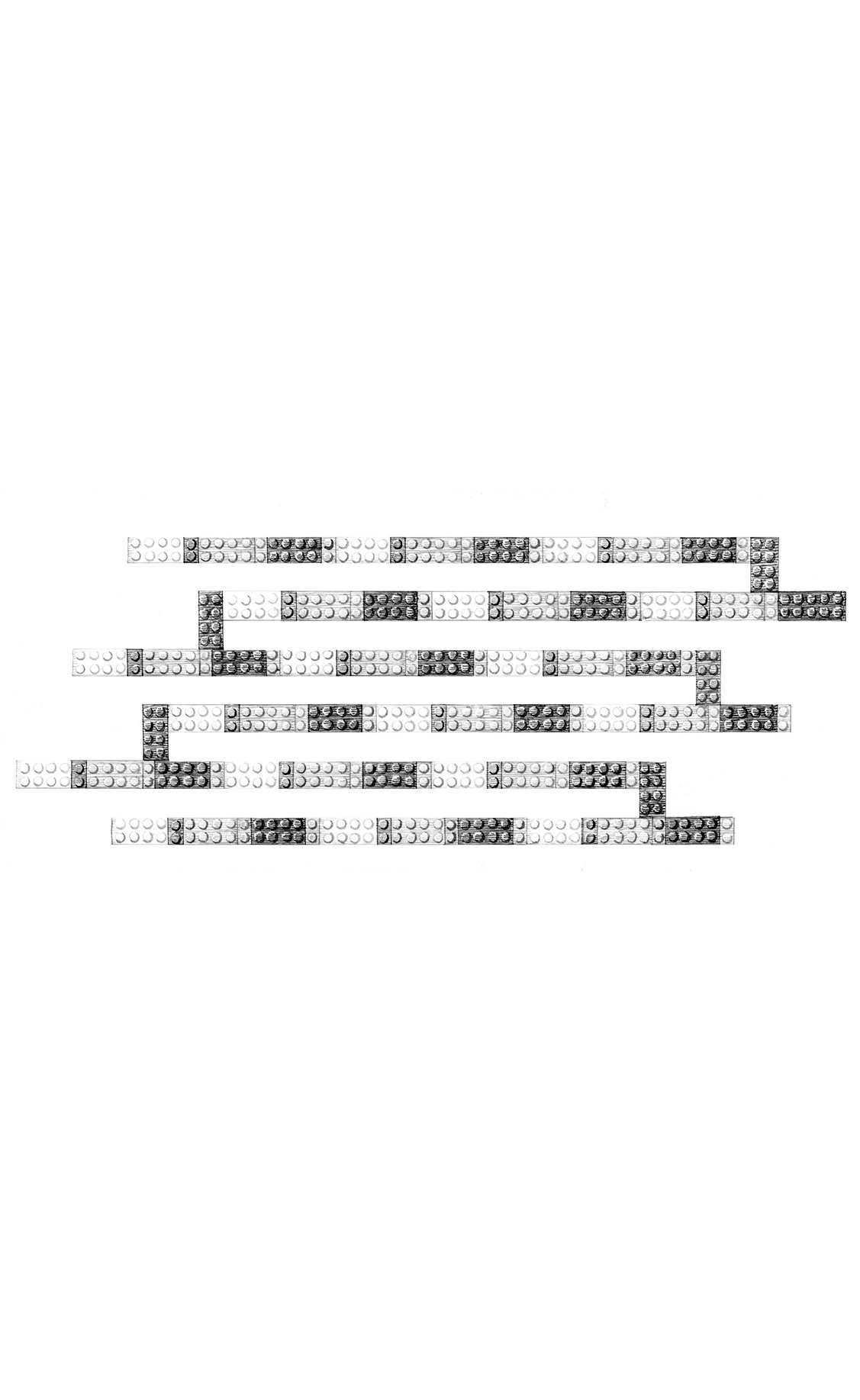

However, as I watched Danny picking the Lego bricks out of the box and laying them on the floor, I saw that he wasn’t using them to build a house or car or any other object; he was arranging them end to end in a line. After a few minutes it was clear he was creating a multicoloured line of bricks, and I saw a pattern emerging from the different brick sizes and colours he was using: large white, small pink, large yellow, small red, blue, green, etc. I watched, impressed, as he concentrated hard and carefully selected each brick from the box and added it to the line. When the pattern had repeated three times he placed a large blue brick at right angles to the previous red brick to turn the corner, then added a green one at right angles to that and started creating a second line running parallel to the first with an identical repeating pattern. I’d never seen a child use Lego like this before, so intricate and precise. Maintaining the pattern he completed a third and then a fourth line, then halfway through the fifth line he ran out of red and blue bricks. He looked at the house Paula had previously built, which was an arbitrary arrangement of red, yellow and blue bricks.

I immediately realized what Danny wanted and called through to Paula, who was still at the dining table talking to Adrian and Lucy. ‘Is it all right if Danny breaks up your Lego house so he can use the bricks?’ I didn’t think she’d mind, but it seemed right to ask her.

‘Sure,’ she called back easily.

‘Go ahead,’ I said to Danny. ‘You can use Paula’s house.’

He picked up the Lego house and carefully dismantled it, then separated the bricks into their different colours. He completed a fifth and sixth line of bricks in the same sequence. There were six bricks left over and he returned those to the box. He then carefully put the lid on the box and pushed it away, out of sight, as though he didn’t want to be reminded of the rogue bricks that hadn’t fitted in. He sat back and contemplated his work. It had taken him about fifteen minutes.

‘Well done,’ I said, going over. ‘That’s a fantastic pattern.’

I called to Adrian, Lucy and Paula to come and see what Danny had made and they dutifully traipsed in. But once they caught sight of his innovative use of Lego their expressions changed to surprise and awe as they admired the impressive six-line sequenced pattern. Here was a child with learning difficulties and very limited language skills producing a complex pattern.

‘That’s better than my house,’ Paula said kindly.

‘It’s the work of a genius!’ Lucy declared.

‘Where did you get that idea from?’ Adrian asked, obviously impressed.

Danny didn’t answer.

I assumed Danny would be pleased with the praise and admiration he was receiving – most children would be – and that he would show it by smiling, but he didn’t. His face remained expressionless, as it often was, and he continued to stare at the Lego pattern.

‘Very good,’ I said again. ‘We’ll leave it there while we have some dessert.’

‘What is for dessert, Mum?’ Adrian asked.

And before I could answer, without looking up, Danny said, ‘Ice cream and chocolate pudding.’

‘That’s right, Danny,’ I said. ‘Well done. We’re having ice cream and chocolate pudding. Let’s go to the table and have some now.’

Although Danny hadn’t acknowledged me when I’d mentioned dessert earlier in the car, he’d clearly taken it in and remembered what I’d said. His words had come out so quickly and on cue it was as though he’d had them ready at the forefront of his mind, for when they might be needed, whereas it seemed that if I said something new to him there was a delay before he responded, as though he needed time to process the information.

Leaving the Lego, Danny stood and we went into the kitchen-cum-dining-room where the children returned to the table and I went to the kitchen. I heated the chocolate pudding and spooned it into the dessert bowls, then added a generous helping of ice cream on top of each pudding. My children and I loved it served this way so that as the ice cream melted it created a delicious combination of taste and texture, hot and cold. I assumed Danny would like it too – all the other children we’d fostered had – but as the rest of us began eating Danny spent some time scraping the ice cream from the top of his pudding before he made a start. Then he ate the ice cream first, followed by the pudding.

‘Do you prefer your ice cream separate?’ I asked him.

He gave a small nod.

‘I’ll remember that for next time,’ I said. ‘If I forget you must tell me.’

It was only a small point but accommodating a child’s preferences, likes and dislikes helps them settle in and feel part of the family. Danny finished all his pudding and scraped his bowl clean. I was pleased he’d eaten a good meal. He was very slim and needed to put on some weight.

It was after seven o’clock now and I thought I should start Danny’s bedtime routine. He was only six years old and he’d had a very traumatic day. I was sure that once he’d slept in his room and enjoyed a good night’s sleep everything wouldn’t seem so strange to him and he’d start to feel better. I explained to him that it was time for bed and that I’d take him upstairs and help him get ready. He didn’t look at me as I spoke – his gaze was down – but he seemed to be concentrating and taking it all in. I asked him if he’d like a bedtime story before we went up, but he shook his head.

‘Would you like to see the other rooms in the house now?’ I asked. He’d only been in the living room and the kitchen-cum-diner.

Danny shook his head again, but then asked, ‘George?’

‘George is in bed,’ I said, hoping this was the right answer. ‘And you’ll see Mummy tomorrow at school,’ I added.

‘Daddy?’ he asked.

‘I expect Daddy’s at your house.’ I didn’t know if this was true, but it seemed a reasonable assumption given that Danny lived with both his parents and it was evening. Danny accepted this.

‘Would you like to say goodnight to Adrian, Paula and Lucy?’ I asked him. He looked away awkwardly and didn’t reply, so they said goodnight to him.

I offered Danny my hand to hold but he didn’t take it, so I led the way into the hall. As we passed the living room he looked in to check on the Lego. ‘We can leave the Lego as it is until tomorrow,’ I said.

He gave a small nod, and then came with me down the hall. Adrian had previously taken Danny’s holdall upstairs and placed it in his bedroom. As we passed the spot in the hall where the holdall had been Danny stopped and pointed.

‘Your bag is in your bedroom,’ I said.

Then he pointed to his coat, now hanging with ours on the coat stand. ‘Your coat is with ours ready for when we go out in the morning,’ I said.

He wasn’t reassured and began waving his arms agitatedly.

‘What’s the matter?’ I asked. ‘Your coat will be safe there.’

He flapped his arms more vigorously and then began rocking back and forth on his heels while making a low humming noise, clearly heading for another tantrum.

‘Enough, Danny,’ I said firmly. ‘I need to know what you want so I can help you.’

He started tugging at his coat, so I assumed he wanted it, but it was too high up for him to unhook.

‘OK. Stop,’ I said. ‘I’ll reach it down for you once you’re calmer,’ and I waited for him to relax. While giving him his coat wasn’t an issue – he could take it upstairs with him if it made him feel more secure – I didn’t want him to think that throwing a tantrum would get him what he wanted. He had some language skills and he needed to use them.

Gradually Danny grew still and became less agitated, so I took his coat from the stand and gave it to him. He didn’t put it on or clutch it protectively to his chest as he had done before; instead, he began reaching up to the coat stand again.

‘Do you want to hang it up yourself?’ I asked, having seen many toddlers do this.

Danny nodded.

‘Would you like me to lift you up so you can reach it?’

He nodded again.

He let me put my hands around his waist, and I lifted him up until he was high enough to hook his coat onto the stand. Then I set him on the floor again.

‘Thank you,’ he said quietly, without looking at me.

‘You’re welcome. It’s always best to try to tell me what you want, then I’ll know and can help you.’

I offered him my hand to hold to go upstairs but again he refused it, using the banister rail for support instead. Upstairs I showed him where the toilet was and asked him if he needed help. He shook his head, so I waited outside. I heard the toilet flush and then the taps run. He came out and I led the way to his bedroom.

‘This is your bedroom,’ I said. ‘I hope you like it. It will be better once you’ve got your things around you.’

Danny didn’t comment, nor did he look around the room, but he went to his holdall and unzipped it. At the top lay a soft-toy rabbit, which he picked up and held lovingly to his cheek.

‘George,’ he said with a small sigh, and for the first time since he’d arrived I saw him smile.

Chapter Four

Precise

I was upstairs for two hours helping Danny get ready for bed. He didn’t have a huge amount in his holdall – there was a couple of changes of clothes, pyjamas, a towel and wash bag – but Danny insisted on unpacking it all himself, and he was very precise. First he spent some time deciding which drawers to put his clothes in, then he spent a long time arranging them and rearranging them until, mindful of the time, I began chivvying him along. Once he was satisfied that his clothes were in the right drawer and positioned correctly he spent more time arranging his soft toy rabbit on the pillow, repositioning it in a number of different places.

‘It won’t ever be quite the same as at your house,’ I said, for clearly Danny couldn’t replicate exactly what he had at home.

But Danny continued until he was satisfied, and then finally changed into his pyjamas, neatly folding the clothes he’d taken off and placing them squarely at the foot of his bed, as I guessed he did at home. Eventually we went round the landing and into the bathroom. I showed him where everything was, and he spent some time arranging his towel and wash things beside ours. He was probably the most precise and self-sufficient six-year-old I’d ever come across, yet at the same time there was a vulnerability about him that was younger than his years.

‘You can have a bath tomorrow evening,’ I told him. ‘There isn’t time tonight. A good wash will be fine for now.’

Danny didn’t object and I placed the childstep in front of the hand basin so that he could comfortably reach into the bowl. He then spent some moments repositioning the step, squaring it, before he was satisfied and finally stood on it. I put the plug into the sink and turned on the taps. Danny turned them off, and then on again, wanting to do it himself.

‘The water is hot,’ I said, turning down the hot tap. ‘I need to help you with this.’ His face set; he didn’t like my interference, but he was six, and in some things he had to accept my help for his own safety. ‘Hot water can burn you,’ I told him.

He didn’t reply but stared blankly at the sink. I ran the water and checked the temperature. ‘That’s fine now,’ I said. ‘Do you want me to wash your face, or can you do it?’

There was pause before he picked up his flannel, folded it in half and half again, carefully submerged it in the water, squeezed it out and began washing his face. ‘Good boy,’ I said.

As Danny washed and dried his face and then cleaned his teeth, I saw there was something measured, almost ritualistic, in the way he performed the tasks. I guessed he carried them out exactly the same way every evening. In cleaning his teeth he carefully unscrewed the cap of his toothpaste, set the cap to one side, squirted a precise amount of paste onto his toothbrush, put down the brush, screwed the cap back on the paste and then began cleaning his teeth. Such exactness was very unusual for a child, and of course it was a slow process. I realized we would have to start the bedtime routine earlier in future. When Danny brushed his teeth the movement was so regular that it created a little rhythm as the brush went back and forth over his upper front teeth, then the left and right, and the same on his lower teeth. But he appeared content, as though he enjoyed the feel of it. I began to think he could continue indefinitely, so eventually I said, ‘You’ve done a good job, Danny. You can rinse out now.’

There was a pause before he did as I’d asked. Then he patted his mouth dry on his towel and returned it to the rail, where he spent some moments squaring it before he was satisfied. I wondered how much of his precise and ritualistic behaviour was because he was anxious and how much was just part of Danny. He was certainly an unusual little fellow, and I clearly had a lot to learn about him.

It was now nearly nine o’clock, and while I’d been upstairs Adrian, Lucy and Paula had come up and were in their rooms getting ready for bed. As Danny and I went round the landing I pointed out everyone’s bedrooms, but he didn’t want to look in.

‘If you need me in the night, call out and I’ll come to you,’ I said. ‘There is a night light on the landing, but I don’t want you wandering around by yourself. So call me if you need me.’ I told all the children this on their first night, although given Danny’s lack of language I doubted he would call me. I was a light sleeper, though, and usually woke if a child was out of bed. We continued into his bedroom. ‘Do you want your curtains open or closed?’ I asked him, as I asked all children when they first arrived.

Danny didn’t reply and looked bewildered. ‘They are closed now,’ I said. ‘Are they all right like that?’

He gave a small shake of the head and then went over to the curtains and parted them slightly.

I smiled. ‘Good boy. I’ll know what you want next time. Do you sleep with your light on or off?’ This was also important for helping a child settle.

Danny didn’t say anything but went to the light switch and dimmed it.

‘That’s fine,’ I said. ‘Is there anything else you need before you get into bed?’

He shook his head and climbed into bed, then snuggled down. He pulled the duvet right up over his head and drew the soft-toy rabbit beneath it.

‘Won’t you be too hot like that?’ I asked him.

There was no reply.

I tried easing the duvet down a little away from his face so he could breathe, but he pulled it up over his head again.

‘All right then, love. I’ll say goodnight.’ It was strange saying goodnight without being able to see his face. Often a child wanted a hug or a goodnight kiss, or, missing home, asked me to sit with them while they went off to sleep. Clearly Danny didn’t want any of these.

‘Night then, love,’ I said to the lump in the duvet that was Danny. Silence. ‘Do you want your door open or closed?’ I asked before I left.

There was no answer, so I left the door slightly ajar and came out. I’d check on him later. Yet as I went round the landing to Paula’s room I heard Danny get out of bed and quietly close his door. He had known what he wanted but hadn’t been able to tell me. Whether this was from poor language skills, shyness or some other reason I couldn’t say.

Once I’d checked that Paula, Lucy and Adrian were OK and getting ready for bed, I went downstairs. I would go up later when they were in bed to say goodnight. I was exhausted, but I knew I should write up my fostering notes before I went to bed while the events of the day were still fresh in my mind. All foster carers in England are asked to keep a daily log in respect of the child or children they are looking after. They record any significant events that have affected the child, the child’s wellbeing and general development, as well as any appointments the child may have. It is a confidential document, and when the child leaves the foster carer it is sent to the social services, where it is held on file.

I sat on the sofa in the living room with a mug of tea within reach and headed the sheet of A4 paper with the date. I then recorded objectively how I’d collected Danny from school and the details of how he was gradually settling in, ending with the time he went to bed and his routine. I placed the sheet in the folder I’d already begun for Danny, and which would eventually contain all the paperwork I had on him. I returned the folder to the lockable draw in the front room and went upstairs to say goodnight to Paula, Lucy and Adrian. Then I checked on Danny. He was still buried beneath the duvet and, concerned he would be too hot and breathing stale air, I crept to the bed and slowly moved the duvet clear of his face. He was in a deep sleep and didn’t stir. His cheeks were flushed pink, and his soft-toy rabbit lay on the pillow beside him. Danny looked like a little angel with his delicate features relaxed in sleep and his mop of light blond hair.

I checked on him again at 11.30 before I went to bed, and then when I woke at 2 a.m. Both times he was fast asleep, flat on his back, with his face above the duvet and soft-toy George beside him. I didn’t sleep well – I never do when a child first arrives. I subconsciously listen out for the child in case they are upset. But as far as I was aware Danny slept soundly, and he was still asleep when my alarm went off at 6 a.m. I checked on him before I showered and dressed, then again before I went downstairs to feed Toscha and make myself a coffee. At 7 a.m., after I’d woken Adrian, Lucy and Paula, I knocked on Danny’s door and went in. He was awake now, still lying on his back but with his arm around the soft toy and staring up at the ceiling.

‘Good morning, love,’ I said, going over to the bed. ‘You slept well. Did you remember where you were when you woke?’

His gaze flickered in my direction, but he didn’t make eye contact. Then he spoke, although it wasn’t to answer my question.

‘For breakfast I have cornflakes, with milk and half a teaspoon of sugar,’ he said.

I smiled. He had clearly prepared this speech, and I wondered at the effort that must have gone into finding the correct words and then keeping them ready for when they were needed.

‘That sounds good to me,’ I said. ‘I want you to wash and dress and then we’ll go down and have breakfast.’

I looked at his little face as he concentrated on what I’d said and tried to work out if a response was needed, and if so, what.

‘So the first thing you need to do is get out of bed,’ I said. I appreciated that Danny needed clear and precise instructions. There was a moment’s pause before Danny pushed back the duvet and got out of bed. ‘Good boy,’ I said. ‘The next thing you need to do is go to the toilet and then the bathroom so you can have a wash.’

Danny turned, not towards the bedroom door but to where his clothes were at the foot of the bed. He stared at them anxiously.

‘Do you usually put your clothes on first?’ I asked him.

He nodded.

‘That’s fine, but you’ll need clean clothes. I’ll wash those.’ I usually replaced the child’s clothes with fresh ones when they took them off at night, but I hadn’t had a chance the previous evening. I went to the chest of drawers where Danny had put his clean clothes and opened the drawer. Danny arrived beside me, wanting to take out what he needed himself.

‘I’ll put your dirty clothes in the laundry basket,’ I said.

He shook his head and, setting down his clean clothes, picked up the dirty ones, again clearly wanting to do it himself. ‘OK. I’ll show you where to put your laundry,’ I said. But Danny went ahead. I followed him round the landing and then waited just outside the bathroom while he put his clothes into the laundry basket. He’d obviously remembered seeing it the night before.

‘Good boy,’ I said.

He used the toilet and then we returned to his bedroom. I was on hand to help if necessary. Before he began dressing Danny laid out his clothes on the bed in the order in which they would go on. His vest at the top, beneath that his school shirt, then his jumper, pants, trousers and socks. I wondered if this was a system he’d thought of to help him dress or if it had been devised by his parents. Special needs children often struggle with sequencing tasks like this that appear simple to the rest of us; they can easily put their vest on over the top of their shirt, for example. Danny’s system worked. Slowly but surely he dressed himself and didn’t need my help.

‘Well done,’ I said as he finished.

He didn’t reply but now concentrated on folding his pyjamas – precisely in half and half again – and then tucked them neatly under his pillow. He carefully positioned his soft toy, George, on his pillow and then drew up the duvet so just the little rabbit’s face peeped out. After that he spent some moments readjusting the duvet until I said, ‘Time to go downstairs for breakfast now.’

He finally stopped fiddling with the duvet and came with me. At the top of the stairs I offered him my hand, and for a second I thought he was going to take it, but then he took hold of the handrail instead. Because Danny was quite small he navigated the steps one at a time, as a much younger child would. He then came with me into the kitchen-cum-diner and went straight to his place at the table.

‘Good boy,’ I said again.

Adrian came down and took his place at the table. ‘Hi, Danny,’ he said. ‘How are you?’

Danny didn’t answer but did look in Adrian’s direction.

‘Toast and tea?’ I asked Adrian, which was what he normally had for breakfast during the week.

‘Yes please, Mum.’

In the kitchen I dropped two slices of bread into the toaster, poured Danny’s cornflakes into a bowl, added milk and sugar and then placed the bowl on the table in front of him. He picked up his spoon and began eating, clearly used to eating cornflakes. ‘What would you like to drink with your breakfast?’ I asked Danny.

There was silence. His spoon hovered over his bowl and he concentrated hard before he said, ‘I have a glass of milk with my breakfast.’

I poured the milk, gave it to Danny and then joined him and Adrian at the table. The girls came down and said hello to Danny, then poured themselves cereal and a drink. As we ate, Lucy and Paula tried to make conversation with Danny, asking him what he liked best at school and what his favourite television programmes were. He didn’t answer, and I could see he was growing increasingly anxious at their questions, although of course they were only trying to be friendly and make him feel welcome. Danny appeared to be a child who needed to concentrate on one task at a time, and he finally stopped eating.

‘I think Danny is finding our talk a bit much first thing in the morning,’ I said as diplomatically as I could.

‘I know the feeling,’ Adrian added dryly.

‘Watch it,’ Lucy said jokingly, poking him in the ribs.

But the girls understood what I meant and not usually being great conversationalists themselves first thing in the morning, they left Danny to eat. Once I knew more about Danny’s difficulties I’d be better equipped to explain them to Adrian, Lucy and Paula, and also to deal with them myself. At present I was relying on common sense and my experience as a foster carer.