Полная версия

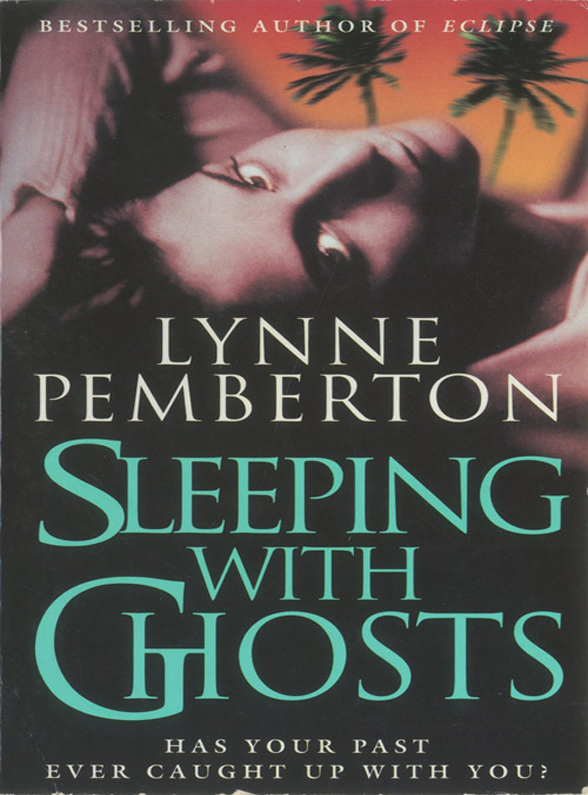

Sleeping With Ghosts

LYNNE PEMBERTON

SLEEPING

WITH GHOSTS

Dedication

This book is for my mother.

I love you very much.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter One

‘SS Oberführer Klaus Von Trellenberg was your grandfather.’ Stunned into silence, Kathryn felt an impulse to laugh. But Aunt Ingrid’s face was stern.

In the same impartial tone, the revelation was repeated, the words exploding like shards of broken glass that shattered the stillness.

‘SS Oberführer Klaus Von Trellenberg was your grandfather.’

Kathryn felt her jaw drop and couldn’t stop it. The shock induced a faint trembling and she drew in a long breath as her aunt continued.

‘Freda refused to discuss the past. It never happened, she buried it, her childhood in Germany, the war, everything that had gone before 1945 ceased to exist. She reinvented herself, erasing her Prussian past to embrace a new identity here. I think she almost believed she was English.’ A harsh guttural sound tinged her voice with bitterness. ‘I never understood Freda, we were total strangers; how we ever sprang from the same womb is beyond me.’

‘Is this why you wanted to see me, to tell me that my grandfather was a Nazi?’ Kathryn sneered. ‘Is this some kind of joke? My mother’s father an SS officer? It’s ridiculous! Her father was Kurt Hessler, a factory worker killed on active duty in 1943. He was your father too, Ingrid, you should know.’ Kathryn tried to contain the hint of fear entering her voice. ‘And your mother died of tuberculosis before the war.’ The doubt in Kathryn’s words begged to be assuaged. ‘Didn’t she?’

Ingrid was shaking her head, eyes narrowing to thin slits full of derision, and Kathryn felt a strong urge to slap her aunt’s face.

‘Your grandmother was a Prussian aristocrat. She died in Berlin at the close of the war. She killed herself.’ Ingrid’s mind drifted back to a cold January in 1945. The memory of that night, repressed for so long, flooded her mind; so lucid it startled her, and she squeezed her eyes tightly shut. Yet the image had come to life, moving through her head like the jerky silent movies she had watched so avidly as a child. She saw herself sitting on the edge of her bed in the Von Trellenberg house in Berlin. She was shivering not from cold, but from fear, and she knew she must get down to the cellar quickly. With hands clamped to her ears, to shut out the terrible sound of bombs dropping all around, she remembered calling first for Freda, then her mother, as she ran out of her bedroom and down the long hall towards her mother’s room. Up till this moment the memory had always been in black and white, and now for some reason it was a vivid colour.

Her mother was dressed in an emerald green taffeta ball gown; her limp body looked like that of a rag doll hanging from the makeshift gallows erected from a bedpost and library ladders.

The sound of the air raid faded to nothing as Ingrid’s screams, and the hammering of her own heart, filled her ears. Luize Von Trellenberg was wearing matching green silk shoes, one of which hung precariously from her big toe, the other had fallen to the floor. With a shudder, Ingrid remembered tripping over that shoe as she stumbled out of the room. She also remembered banging her head, and thought how strange it was that she should recall this now – after fifty years. She remained lost in thought as Kathryn spoke again.

‘Are you trying to tell me that it was all lies: my mother’s childhood in Cologne; her parents; the house where she was born, and grew up; the house that was bombed to the ground? Answer me, Ingrid, was it all lies?’

Ingrid forced herself to concentrate on the beautiful face of her niece, not beautiful at the moment actually, she noted, but contorted with outrage. Still she did not reply.

‘Do you really expect me to believe that my mother’s entire past life has been a complete fabrication, and that this Von Trellenberg person, this Nazi, was my grandfather?’

Kathryn’s tone reeked of dissent and Ingrid sprang to her defence. ‘Your grandfather was an aristocrat, he was a wonderful man, well respected, much loved; you have Von Trellenberg blood, you should be proud. Your great-grandfather Ernst was a national hero, a highly decorated general in the First World War.’ Her speech slowed down, dropping pitch, and she emphasized each word distinctly as if speaking to a child, or someone who didn’t understand the language. ‘Your mother was born in our country Schloss, near Mühlhausen in East Germany, and Joachim and I were born at 42 Regerstrasse, our house in Berlin. We are aristocrats, born into great wealth and privilege; we had nannies, servants, private tutors, and we lived in grand houses, surrounded by beautiful things. If it hadn’t been for the war, we would have …’ Ingrid stopped abruptly and dropped her head.

When she lifted it again, Kathryn was certain her aunt was going to cry. Yet beyond the thin film of tears, there was something else: a burning resentment. And Kathryn had to resist the urge to remind her aunt that it was Germany who had started the war.

Ingrid stared for several minutes at Kathryn as if she was invisible. Her voice when she continued had returned to an even tone. ‘Your mother chose to deny her past; but now that she is dead, I wanted you to know, to understand. Even your father had no idea, he was told the same as everyone else.’

Shifting uncomfortably in her hard wooden chair, Kathryn tried to make sense of what the old woman opposite had just disclosed. After a few moments she rose, and pulling herself up to her full height of five foot ten, covered the few steps that separated them.

‘I can’t believe what you’re telling me, Aunt Ingrid. It seems so unreal, like something out of a movie, or the sort of story that makes fascinating reading in the Sunday supplements and only ever happens to other people.’

Kathryn loomed above her aunt who sat bolt upright in the centre of a small sofa, tiny hands clasped tightly in her lap, seemingly oblivious to Kathryn’s bewilderment.

‘You look just like your grandfather, Kathryn; in fact you’re the image of his mother, Eva. She was very beautiful, you have the same flawless skin, and honey-coloured hair.’

Silence so loud it was deafening filled the small room. An icy chill ran up Kathryn’s spine, and her blood went cold.

‘Anyway, I shouldn’t worry about your grandfather now; he died in active service, on 10th November 1944. Suddenly distracted, Ingrid looked past Kathryn towards the bay window overlooking the front garden. ‘I must prune the roses this afternoon. I’ve got a beautiful display, don’t you think?’

Following her aunt’s eyes to the cluttered foliage, Kathryn tried to pick out the rose bushes in the dense and gaudy profusion of untidy bedding plants virtually covering the tiny front garden. Forcing her voice to respond evenly, and thinking how incongruous it was to be discussing an English garden in the same breath as World War Two, and the Nazis, she said, ‘Magnificent, Aunt Ingrid. Mother always said you had green fingers.’

At this Ingrid reached forward, startling Kathryn as she grabbed her bare forearm. Her hand, callused by years of hard work, bit into the flesh as she forced her niece down on to the sofa next to her, so close their thighs touched. Kathryn recoiled from the smell of stale fish in the old woman’s breath when she spoke.

‘I can’t believe your mother ever said anything good about me. Freda hated me. I was the favourite you see, but she thought she was. Oh yes, Freda deluded herself all her life, always so vain and insolent, even as a child, kissing and cuddling Vater. But I knew it was me he preferred, even though she was prettier. I was musical, I played the piano and the violin; my father adored music, he had ambitions for me to become a concert pianist. Father always told me that I was talented, and that I would go far.’

Kathryn thought ironically that had Von Trellenberg lived, he would have been disappointed to see exactly how far his younger daughter had gone. Married at eighteen to a brutal man who had systematically abused her and her son Stefan, one night Ingrid had retaliated – puncturing Karl Wenzel’s lung with a carving knife. He had survived, but only just, and afraid to face his wrath, Ingrid had fled to join her sister in England. Kathryn would never forget her own childish excitement at the prospect of her aunt and cousin coming to live at Fallowfields. She had anticipated fun and laughter to evict the numbing silence that had taken up residence after her father and mother had divorced.

Instead her hopes had given way to bitter disappointment: Ingrid turned out to be surly and bad-tempered, whilst her son Stefan, who at fourteen was two years older than Kathryn, was sullen and menacing in his quiet cunning.

With a pang of contrition, Kathryn recalled her delight when, eighteen months later, Ingrid and Stefan had moved out. Ingrid, at Freda’s insistence, had found a job as a seamstress at a shop in the small town of Cranleigh. With grudging reluctance, Freda had then bought her a cottage on the outskirts of the town and, having done so, felt no more obligation to the younger sister she had always detested.

Last week, at her mother’s funeral was the first time Kathryn had seen her Aunt Ingrid for fifteen years. She had aged beyond recognition: an old woman standing alone in the church vestibule, leaning heavily on a walking stick, her face framed by a shock of white hair that could have been momentarily mistaken for a hat. It wasn’t until this figure was joined by a tall, good-looking young man that Kathryn knew it was her Aunt Ingrid. She would never forget Cousin Stefan’s penetrating midnight blue eyes; his gaze had terrified her when she was twelve, and it was still chilling twenty-two years later.

Ingrid began to rock to and fro, gazing unblinking into space. With a sense of shock, Kathryn stared into the liquid depths of her vacant eyes thinking about something her father used to say to her mother. ‘Your sister’s not all there.’ As a child, Kathryn had always wondered what piece was missing. With increasing unease, she chose her next words carefully.

‘You and Freda changed your name to “Hessler” – why?’

A hush followed, then Ingrid uttered a soft moan and answered. ‘It was Freda’s idea. She said it was best to assume new identities in order to make a fresh start, because it would be simpler.’ Ingrid could hear her sister’s voice as clearly as if it were yesterday: We must reinvent ourselves; the children of Nazis will be ostracized and made to suffer, like the Jews. It’s for the best, Ingrid, believe me …

‘When the war ended, I was only sixteen. But Freda was eighteen and very strong-willed; all she could think or talk about was how she intended to leave Germany and start afresh. She was very attractive, in a sultry sort of way; everyone told her she looked like Marlene Dietrich, but I could never see it. Before she met Richard, your father, she was sleeping with an American officer. I can’t remember what he was called now, it was one of those ridiculous American names like “Chuck” or “Brad”. He was working in the office for relocation of refugees. It was all such a mess after the war: misplaced people with no homes, nowhere to go. Anyway, this officer issued false papers for Freda and myself. I wanted to tear them up when Freda told me with triumph that she’d used not only her body to bribe the American, but also a necklace belonging to our mother. A beautiful old piece, that had been handed down through several generations. It was set with over a hundred baguettes, and a fifteen-carat flawless pear-shaped diamond. God knows what a necklace like that would be worth today!’

Ingrid was so preoccupied with her story she didn’t hear Kathryn’s sharp intake of breath, nor did she notice her look of profound shock as she tried hard to absorb what her aunt was telling her.

Kathryn had always known her mother was determined, but to prostitute herself ? She found it hard to accept she would stoop so low. There were a million and one questions racing around her head, but she kept quiet and allowed Ingrid to continue without interruption.

‘I will never forget the very first time I saw the necklace. I must have been about four or five. My mother was dressed for a state occasion, and I whispered to my nanny that Mama looked like a princess. My mother leaned forward to kiss me, and I stretched on tiptoe to touch the tip of the diamond drop gleaming against her bare neck. Her perfume filled my nostrils as she whispered in my ear, “This necklace will belong to you one day, my little Ingy.”

‘So you can imagine, the thought of some loud American woman, strutting around in a seventeenth-century Von Trellenberg heirloom, made me feel physically sick. But Freda merely pooh-poohed my protests, insisting that desperate means required desperate measures, and that if we were to go forward we had to forget the past. Then Freda got sick, and as usual got lucky, meeting your father like she did during her stay in hospital.’

Ingrid felt the old familiar stab of jealousy as she recalled her elder sister’s excitement at falling in love with the handsome English doctor, Richard de Moubray, who had asked her to marry him.

‘I begged Freda to take me with her to England, to a new life, but she was so full of herself and so madly in love with your father that the last thing she wanted was a sister to worry about. She thought I would be a burden.’ Pausing for a moment, eyes beginning to dart from side to side as if searching for something she had lost, Ingrid’s voice became ragged and disjointed as she muttered incoherently under her breath in German.

Kathryn watched the old woman in morbid fascination as she resumed her account. ‘I was wretched after the war, a helpless young girl, barely sixteen, a child. I had lost my family, and everything I held dear. For a while I hated my mother for committing suicide, I was very angry and I blamed her for leaving me. Only later, after I had found and read her letters, did I realize how desperate and how very sick she was in the last months of her life. Her adored son Joachim had died of gunshot wounds in a French field hospital in 1944, two weeks before his twenty-first birthday. Four months later her beloved Klaus suddenly stopped writing, and in the ensuing weeks all contact between them ceased. She tried without success to locate him. She was certain that he had deserted Germany, and his family, for ever – afraid of recriminations because of his Nazi connections. The vast country estate was requisitioned by the government, a fortune in antiques and art were looted by the Russians, I believe she even sold her priceless Fabergé egg collection. We lost everything.’

Ingrid’s lids fluttered then closed as if to shut out the memory. She began to pick manically at the tattered remains of a fringed cushion near her lap, a dark blue tangle of veins clearly visible under her papery skin. ‘Freda left not long after that and I was left stranded in that huge empty house. I hid most of the time, afraid to go out; the Russians were everywhere. I had no money or food, I was alone, except for the ghosts. At one point, I thought I was going insane, and if I hadn’t met Karl Lang when I did, I might have done so. Or joined my poor mother. I must admit, in the long, dark nights, I thought about ending it many times, anything would have been preferable to that terrible fear.’

A lump formed in the back of Kathryn’s throat and she swallowed with difficulty. The face next to her, loose and dulled with age, had suddenly reverted to that of a frightened young girl, alone in Berlin amidst the chaos of defeat. It filled her with an unexpected sympathy for this desolate old woman, who had lost her entire family in the space of a few months. It also confirmed what she had always suspected about her own mother. Freda had been a cold, callous creature, unable to love, or even show compassion to her own sister.

‘I’m sorry.’ Kathryn said kindly. She knew it sounded lame, but could think of nothing else to offer. Gently she placed a hand on Ingrid’s lap, but the old woman pulled back from her touch.

‘It’s over now, thank God; all over a long, long time ago, so long I sometimes imagine that none of it ever really happened or that I dreamt it all.’

A snuffling, followed by a scratching noise, momentarily distracted them both; they looked towards the sound, made by a West Highland Terrier, pushing his wet nose around the door.

‘Come, Sasha!’ Ingrid called affectionately. The dog’s ears pricked up instantly and he trotted towards her, leaping on to the sofa to settle in her lap. Ingrid patted the dog’s head, brightening a little. ‘Well, I have a new life now,’ waving a hand around the shabby room. ‘My pretty cottage, and my garden.’

‘Are you sure my father never knew the truth?’ Kathryn asked.

Ingrid shook her head. ‘As far as I know, Freda told him the same as she told you, and everyone else: that she was Freda Hessler, born in Cologne, you know the rest.’

Kathryn took a deep breath, knowing how important the next question was. ‘OK, now about my grandfather …’ She was surprised her voice sounded so calm. ‘Was Klaus Von Trellenberg one of those despicable Nazi monsters?’ Kathryn felt her mouth dry up, as she watched a muscle in Ingrid’s jaw twitch uncontrollably.

The old woman began to shake and Sasha growled softly. ‘My father was an officer, an SS Oberführer. He was an aristocrat, a highly respected man and a good German, who served his leader and his country with loyalty and integrity.’

Kathryn persisted, her sense of outrage and shock spurring her to confront the question uppermost in her mind. ‘You haven’t answered my question, Aunt Ingrid. Was he guilty of war crimes? I need to know.’ Kathryn was almost shouting. She was also tempted to grab her aunt by the scruff of her slack neck, and wring the truth out of her. Shit, the old witch is so controlled, she thought, and in that instant was reminded of her own mother Freda, always calm in crisis, so damn cool, when all around were reeling.

‘Ingrid, look at me please.’ Kathryn ordered.

Her aunt obliged, but her eyes were dead.

‘I accept that this man, this Nazi, Von Trellenberg, was my maternal grandfather. If he was a war criminal, I have to come to terms with that.’ She spat the words out as if eager to be free of them. ‘For God’s sake, Ingrid, I deserve to know; because if he was, it would help explain a lot of things I never understood about my mother.’

Ingrid stood up. She was a few inches shorter than Kathryn, but her back was ram-rod straight, and her thick hair rising from the top of her head like a white busby brought her almost level with her niece. She faced Kathryn, her eyes openly hostile. ‘I want you to go now, please, I’ve got a lot to do.’

Kathryn was furious. ‘That’s great, Ingrid, thanks a lot! I don’t see you for countless years, then my mother dies, and you drag me down here to tell me all about her secret past. Well, I’ve listened to your revelations patiently, and I don’t mind admitting I’m deeply shocked. Who wouldn’t be? It’s a lot to take in all at once.’ Bright spots danced at the corner of Kathryn’s eyes, and she was vaguely aware of a dull ache in her left temple.

When her aunt did not answer, Kathryn added, ‘Listen, I can easily find out the truth by researching the archives in Washington or Germany, so don’t lie to me, Ingrid.’

Screwing her eyes tightly shut, Ingrid dropped her voice to a hoarse whisper. ‘I refuse to discuss my father further. Klaus Von Trellenberg is dead; let him rest in peace.’

The hot sun streaming through the car window was very warm, heating her bare arms, but it couldn’t penetrate the cold numbing horror inside. The letters ‘SS’ and all the horror they conveyed kept leaping into her head, accompanied by a multitude of images from films: jackbooted Nazis, with merciless eyes and arrogant poise, wretched hordes of men, women and children herded on to trains for their journey to genocide.

Holding the wheel very tight, her knuckles bone white, she forced herself to erase the picture of a Jewish child in a red coat. It was a scene from Schindler’s List; the child’s face had remained with her for weeks after she had seen the film, and now it returned to haunt her once more.

Turning left off the main road, she drove up a narrow dirt track stopping at Northfields Farm. Kathryn read the name on the gate several times in an attempt to calm her nerves; then, letting her head drop on to the back of the driver’s seat, she began to shake, an uncontrollable quaking that terrified her. She stumbled out of her car, walked up to the gate and, leaning against it, gazed across a deep meadow where cows were grazing. From a clump of trees to the left she could hear the faint gurgle of a stream, the grass smelt fresh from a shower earlier and the sun was sparkling on new puddles. A large cow, the biggest of the herd, ambled slowly towards the gate, stopping a few feet from where Kathryn stood. Out of eyes the colour of dark chocolate, the animal surveyed her with mild curiosity. The intense pounding in her head started to abate, and with it the panic she had experienced earlier gradually subsided.

Kathryn stood very still for several minutes. The dull drone of insects in the hedgerows and the muted rumble of a tractor in the far distance were the only sounds breaking the stillness of the hot afternoon. She lifted her eyes to a cloudless blue sky and watched a lone wood pigeon swoop low to peck in the long grass behind the cow, who flicked her long tail angrily several times until the bird took flight.

Kathryn felt a comforting return to normality. She had no idea how long she had been there, and was surprised when she returned to her car, to see that it was ten past two. She had been standing by the gate for over half an hour and was going to be late for a two-thirty appointment in Westerham.

As she turned the key in the ignition and drove off, she thought about Ingrid’s insistence at her mother’s funeral, and during three subsequent telephone calls, that it was of the utmost importance they should meet. Kathryn wished she had listened to her first impulse, which was to refuse. She had never liked her Aunt Ingrid, and knew that the feeling was mutual. Ingrid is probably content, thought Kathryn with a smile, now that she’s off-loaded fifty years of repressed emotions on to me.