Полная версия

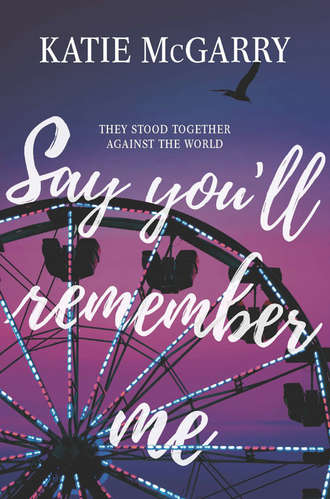

Say You'll Remember Me

I nod, because I have never wanted things to happen because of my father.

“Life is cruel,” Mom says. “It’s hard. Don’t be sad because your father and I are trying to help you avoid the roads that cause pain. Do you have any idea how much I wanted a parent who was involved and supportive when I was younger? Do you know how badly your father wished he had the opportunities you do? We’re not trying to hurt you. We’re trying to help.”

Pain. It’s something both of my parents understand. My mother had every possession she could think of, but her father was a monster, and Dad’s father died when he was young. While my father had a great mom, he understood hunger pains far more than anyone should. Yes, my grandmother had the land, but sometimes farming the land didn’t pay out like they needed, and she stubbornly refused to sell.

Guilt pounds me like a hammer. “I should have told you about the internship.”

Mom stands, places her fingers under my chin and forces me to meet her gaze. Her blue eyes are soft, the stroke of her finger against my hot cheek softer. “I love you, and I hate being harsh with you, but the next few months are crucial for your father and me. We need you. I can’t help but think that if your father and I were more direct with Henry, like we’re being with you today, that he’d still be a part of our family. Henry made terrible mistakes, and I don’t want to see you make terrible mistakes, as well. I understand what real pain is, and everything I’m saying to you, everything I do for you, it’s to keep you from that pain.”

“Henry’s happy,” I whisper.

Mom grows incredibly sad. “He regrets his choices, and he’s too proud to admit he needs our help. I’m starting to wonder if he’s trying to turn you against us so he can make himself feel better—to justify his own bad choices. I know you love him, and I would never tell you to stay away from him, but I am asking you to be careful. Don’t let him influence you away from us.”

A tug-of-war. Mom and Dad pulling on one side. Henry on the other. Problem is, I remember how distant Henry was the summer before he left. Never home. Angry all the time. Moody. It was as if an alien had taken control of his body. “What did Henry do?”

“He doesn’t want you to know, and we promised we wouldn’t tell. Someday, he’ll come home, and we want to keep our promises. Just think of this as a lesson to listen to us. Henry didn’t and he made a mess. You think you know what you want, but trust me, you don’t. Seventeen is too young. Just let us make the decisions for you. You’ll have the rest of your adult life to make all the decisions you want. But these choices now, they’re too big for you to make and the consequences are too dire if you choose wrongly.”

After all my parents have done for me, all the sacrifices they made, both of them coming from painful childhoods, I have to listen. Bruises for Mom, and a farm that barely broke even for Dad, yet they both climbed from misery to success.

I nod, Mom kisses my cheek and she leaves. I have three minutes until I have to pretend in public that the last few minutes didn’t come close to breaking me.

Focus. Mom says I have none, but I do and I’m going to prove it to them. I have to be perfect over the next few months. Dot every i. Cross every t. Show them how passionate I am about coding and prove to them I have focus. I’ll show them responsible. I’ll wow them at every turn. I’ll do everything they need me to do and more.

In the meantime, I have to lie one more time.

The world is eerily hazy as I cross the room, dig the letter out of my bag and unfold it. This letter doesn’t go to the school, but to the company. My counselor won’t know anything until the fall which means Dad has lost his mole.

I’ll have to tell Mom and Dad, when classes resume, but until then I have three months to write as much as I can on this code. By then, hopefully, I’ll be so far into the project, they’ll be amazed that I balanced a schedule full of being on the campaign trail, fund-raisers and this coding that they’ll have no other option but to permit me the opportunity for the internship.

By the end of this, my parents will see me as a success.

Hendrix

“You stay here.” Cynthia, as it turns out, has an intern. She’s in college, and she points at the spot I’m standing in as if I’m a six-year-old with ADD. “Right here. Until the governor calls you onstage.”

In the convention center, at the front of the stage, there are cameras. Row after row of them, and there are people next to them and people behind them. Also in the crowd are the people who have planned to come and see the governor talk, people who are tired of being in the blazing heat and are taking a break inside, and people who are curious to watch the circus.

Come one, come all. Watch the politician smile and lie. Then watch the poor boy say he’s sorry for a crime he didn’t commit, and while I’m at it, watch me pull an elephant out of my ass.

“Once you are onstage, the governor will shake your hand.” Cynthia doesn’t bother looking up from her cell as she talks to me, and with Axle not around, she’s lost the sweet voice. “You will then turn to the podium. The speech is already there. Read it, I’ll select the reporters, you answer the questions and when you’re done speaking, look at me. I’ll signal to you when it’s time for you to walk offstage, and then you will go backstage and wait in the back room until I tell you it’s time to go.”

It’s the last part that catches my attention. “Why do I have to go in the back?”

“In case a stray reporter would want to talk to you. You only talk to people I approve. If anyone ever approaches you without my consent, you tell them that they are to talk to me. Then you contact me immediately. Got it?”

One more chain locks itself around my neck. “Got it.”

Applause breaks out in the crowd, and a man in a suit shakes hands with people as he slowly makes his way to the stage. It’s our state’s governor, Robert Monroe. I’ve never met him before. Feels weird since it’s his program that saved me from hard time.

He passes me, his wife at his side, neither making eye contact as someone like me isn’t worth their time. They then climb the stairs to the stage to join the other people in suits.

“The media loves her,” Cynthia says.

“Who?” The intern rises on her toes to try to see around the crowd that’s now focused on the next person coming up the aisle.

“The governor’s daughter.”

The governor’s daughter. I’ve heard about her. Most everyone has heard about her. Holiday used to talk about her all the time. Something about her being beautiful and poised and up on fashion. Gotta admit, I didn’t listen. I could care less about someone else’s life.

The governor passes by me again, braves his way into the thick of people and when he reemerges, my heart stops. On the governor’s arm is blond hair and intimidating blue eyes. It’s Elle.

The world zones out.

I’m going to strangle my sister if she knew Elle was the governor’s daughter and didn’t say a word. Damn. I flirted with the governor’s daughter. I scrub a hand over my face.

The man I have to impress in order to stay out of jail, the man who can tell my probation officer to flip the switch and send me back behind bars, I flirted with his daughter. I helped his daughter, but then I rejected her. Screw me. I can’t catch a break.

“Ellison,” a reporter calls. She turns her head, and flashes a smile. The reporters and the crowd see what I see—pure beauty in motion.

Elle scans the area, and her smile falters as surprise flickers over her face. But as quick as it’s there, it’s gone, and she returns to perfection. The upturn of her lips is sweet, it’s gorgeous, but it’s not the smile that caused me to feel like a moth to a flame. Earlier, I made her laugh, and she owned the type of smile that becomes seared into a man’s memory.

Elle’s bold. Bold enough to cock an eyebrow at me as she passes. A question as to what I’m doing here. I’ve been asking myself the same question for over a year. She walks up the stairs for the stage, and my stomach sinks.

To one person, for a few moments, I was the hero. Did I step in to help Elle? Yeah. But I also stepped in to help me. Because I’m selfish like that. I needed to know, before I made an announcement to the world I’m a thug, that one person saw me as good.

Now I got nothing.

Elle’s father walks her to the center of the stage, and the cameras remain on them, remain on her. Her smile stays steady, stoic. Her hand curls into the crook of her father’s arm. The governor leans in, whispers something to her and there it is...that smile. The one where those intimidating blue eyes spark.

He covers her hand on his arm, and she raises up on her toes to kiss his cheek. Cameras snap, a sea of cell phones record every second. Then with one last glance at the audience, Elle slips to the back of the stage, next to her mother. Instead of watching the governor as he begins to speak, I watch her, willing her to look in my direction one more time.

Cynthia steps in front of me, blocking my view of Elle. “You ready?”

Adrenaline pumps into my veins, and I scour the area, searching for an exit. Dominic is the one who is claustrophobic, but since being home, I get it. I understand the overwhelming urge to bust out, the need to rip off the chains so I can breathe. But while Dominic’s issues are with walls, my issue is my life. It’s closing in on me, and there’s no escape.

The governor’s voice drones over the audio system, and he talks statistics. Numbers that prove that messed-up boys like me can be helped by people like him. He talks about destroying the school-to-prison pipeline, he talks about juvenile delinquents being given another shot, he talks about second chances and blank slates. My heart pounds in my ears.

“I said, are you ready?” Cynthia prods.

No, I’m not, but I walk for the stage stairs regardless.

My name is said, Hendrix Page Pierce, and the crowd claps. For what I don’t know. The part of me that’s a glutton for punishment wants to gauge Elle’s reaction, but knowing I’ll see disappointment, I keep myself from looking. Some things I don’t need to experience.

I reach the podium, and in a motion so perfect it could have been practiced a million times instead of never, the governor and I shake. He places his other hand on top of our combined hands as if he has to prove he’s in control. As if I don’t know the score.

He leans forward to say, “I appreciate how much courage this takes.”

I appreciate not going to adult prison.

“I’ve heard great things about you. I heard you’re a leader. It’s why we chose you to speak on behalf of the other teens like you, whom we’re going to help.”

A leader. Is he talking about the guy who carried other people’s packs when they were too exhausted emotionally or physically to go forward? The guy who gave up his food when others were complaining they were still hungry? The guy who sat up at night with the two younger teens on the trip who were still scared of the dark?

That doesn’t make me a leader. That makes me a good older brother.

The governor lets me go, inclines his head to the podium, and Dominic’s loud two-finger patented whistle pierces past the polite applause. He’s in the back, Kellen by his side, and when Dominic catches me looking at him, he flips me the bird while giving me a crazy-ass grin.

The familiar reminder of my family causes some of the knots in my stomach to unravel, and it gives me the courage to read the words. That’s all they are, just words. Words that are unrelated. Words that don’t mean anything to me. Words that hopefully won’t mean anything to anyone else.

“One year ago, I made a mistake. One that put my life and the lives of others at risk.”

The speech talks in circles about the crime, but it skips key phrases like convenience store, gun and stolen cash. “I was on a bad road that was going to lead to more mistakes. Mistakes that could never be forgiven.”

I did make mistakes, and I was on a bad road. Living with Mom, I became her. Getting drunk, getting high. Thinking too much of myself, thinking I was as close to a god as a man could get when my mind was in a haze. That’s what happens when someone flies too high: they get burned.

“Once arrested, I confessed to what I did wrong, and I was given a second chance.”

I lift my head to look at Axle, who is now in the back. He has his arm around Holiday, and she has this beaming light about her like she’s proud. I’m not someone she should be proud of, but I want to become that man. I want to be the brother she deserves.

“I’d like to thank Governor Monroe for picking me for his program. In it, I learned how to believe in myself. I learned who I am, and who I am is not the person I was before. I learned I’m capable of more than I could have imagined.”

Light applause and Cynthia steps forward. “We’re allowing a few questions.”

More than two hands raise, and Cynthia points at a man. He introduces himself as a reporter from some newspaper in Louisville. “Can you tell us something you learned during your time in the wilderness?”

I learned I can be alone when I never liked being alone before. I learned the voices in my head that used to taunt me when I was high or alone aren’t as bad as I used to think. I learned, sometimes, those voices have something worth listening to. Like stepping in with Elle. That was worth doing. “I learned how to survive. I learned how to make a fire with nothing but sticks and flint. If anyone needs a fire or help after the apocalypse, let me know.”

Laughter and I glance over at Cynthia. She nods in approval. One down, one more to go, and I can get the hell off this stage.

“Another question?”

More hands go up, and as Cynthia goes to point, a man next to a camera yells out, “What crime were you convicted of?”

“Don’t answer,” Cynthia whispers to me, then motions to the man behind him. “Charles, you can ask your question.”

“It’s a valid question.” The guy continues to talk as if she didn’t ignore him. “How do we know he wasn’t convicted of jaywalking? The type of changes the governor is promising with this program sound good, but how do we know if the results aren’t skewed or tainted?”

My eyes shoot to the back of the crowd, straight to Axle, and my brother’s face falls because we both feel it coming. The tidal wave we felt the rumblings of in the distance is about to crest and hit the shore, destroying me in the process.

“What did you do?” the man shouts again, and when Cynthia turns toward me I see the question on her face. Will I do it? Will I answer and save the governor’s program?

Blank slate. Second chance. Sealed records. All of it is bull.

Ellison

It’s a train wreck, and everyone is watching. Someone needs to do something, and no one is moving. Cynthia wants him to answer the question. It’s also clear, Drix doesn’t want to answer, and I understand why.

“What difference does it make what he did?” I whisper in hopes Dad will hear, but he’s three people away.

My mother shushes me, and Sean, my father’s chief of staff, sends me a glare via certified mail. He and I live in mutual distrust purgatory. To Sean, I’m supposed to be mute and look pretty, but Drix helped me, and staying silent is wrong.

“Mom?” I say, and her head jerks at the sound of my voice. Me speaking onstage without a teleprompter or typed speech is the equivalent of me biting a newborn. “He shouldn’t have to answer.”

“We’ll talk about this later,” she snaps in a hushed tone.

Lydia, my father’s press secretary, walks to the podium with that air of confidence that only she possesses. She’s an intelligent and beautiful black woman who has told me several times that how you walk into a room defines who you are before you open your mouth.

Whenever I see her, I believe this. She demands respect from the moment she comes into view, and I envy her how people so readily give it. “Mr. O’Bryan, I am kindly asking you to wait your turn and wait to be called on before asking questions.”

I’ve seen Lydia at work enough to know that the smile she just flashed Mr. O’Bryan, a loser reporter who has hated my dad for years, is telling him to shut up. There is a hum of uncomfortable chuckles from the families, and Lydia goes on to explain that Drix is still seventeen and that his records are sealed.

She’s saying all the right things, she’s saying all I want to say, but I see it on the faces of the crowd. They want to know what he did so they can judge. Drix’s past defines him, and that’s not fair, especially when it’s his future my father is trying to create. Especially when I know that my father’s program worked.

As Lydia wraps up, Mr. O’Bryan calls out again, speaking over her, “I saw Mr. Pierce and the governor’s daughter on the midway together.”

Lydia freezes her expression, and the entire convention center goes silent.

“The point I’m trying to make,” Mr. O’Bryan says, “is that this program has been the governor’s main priority for over two years. Lots of taxpayers’ money is going into a program we have no idea will work, and the first contact we’ve had from this program was seen, by me, on the midway with the governor’s daughter. This could be a friend of hers the governor has asked to read a speech to make us happy. If Mr. Pierce isn’t willing to tell us about his real past and let us, the press, verify who he is, what he’s done and let us judge how far he’s come, then how do we really know if this program has worked?”

Cynthia whispers to Drix, and he shakes his head slightly. She’s asking him to confess. He doesn’t want to, and he shouldn’t have to. I begin to run hot with the idea that I’m letting him down after what he did for me.

“Is this true, Elle? Were you on the midway with him?” my mother whispers under her breath, and her glare makes me wish I could disappear. Sean superglues himself to my side, and the way my father is eyeing me makes me feel as if I have somehow betrayed him.

“He saved me.” I shake that off because it sounds overly dramatic. “Drix helped me. Some guys were harassing me, and he stepped in to help.”

“What happened to Andrew?” Mom demands.

I shift from one foot to another. “I ditched Andrew.”

Mom’s eyes shut like I announced I kidnapped someone, and Sean pinches the bridge of his nose. “Did Hendrix Pierce get violent with these guys?”

“No. He offered to hang out with me until the guys got the hint that they should leave. Drix never said a word to them.”

“He saved you.”

“Helped me,” I correct Sean.

Sean stares straight into my eyes, and he’s making a silent promise to yell loudly at me later. “No, Elle, he saved you.”

My eyebrows draw together, and before I can ask what he means, Sean takes my hand and pulls me toward the podium. Drix’s head jerks up as I pass, and for the first time since I saw him earlier, he looks at me.

“Excuse me,” Sean says into the microphone. “I’m Sean Johnson, the governor’s chief of staff and Ellison’s godfather.”

People watch him, each of them curious, and I know what Sean has done—humanized himself and me. With a few words, he told everyone he’s in a position of authority, and that he should be respected. Me? I’m still the pretty girl standing beside him.

“We typically don’t allow people like Mr. O’Bryan to shout off like he has, but we’re trying to be respectful. In return we’re hoping he’ll be respectful to the governor and his daughter in the future.”

Lots of mothers shoot death stares in Mr. O’Bryan’s direction, and I’m okay with this. Mr. O’Bryan needs to be digested whole by a T. Rex.

“Secondly, Mr. Pierce confessed to his crime, has served time for it and he has gone through the governor’s program. He has paid his debt to society, and he has learned from his mistakes. To prove it, the governor’s daughter is going to explain the events that happened today on the midway.”

Sean tilts his head to let me know if I screw up I will never be let out in public again.

The lights are brighter than I thought they would be. Hotter, too. Makes it more difficult to see individual faces, makes it more difficult to figure out how many people are staring at me and if they are happy, annoyed or on the verge of rioting.

My mouth dries out, I swallow, then wrap my fingers around the edge of the podium. “Hendrix Pierce helped me today.”

Sean clears his throat.

“Saved me today. I was on the midway, and two college-aged guys began to harass me, and Drix...that’s what Hendrix introduced himself as...he intervened.”

Multiple flashes of light as pictures are snapped, multiple voices as people talk, even louder voices as people ask questions.

Sean talks into the microphone again. “We will take questions, but I want you to remember you are talking to the governor’s seventeen-year-old daughter. I will not allow anyone to disrespect her.”

Sean points, and a woman in the back asks, “You never met Mr. Pierce before?”

I shake my head, and Sean gestures to microphone. “No. I was playing a midway game earlier, and he ended up playing beside me, but then we went our separate ways. I left the game, and these guys started to harass me and then Hendrix asked if I needed help. I agreed, and he suggested we talk. He said that if the guys thought we were friends they would eventually lose interest, and they did. Hendrix played a game, and we talked until Andrew showed.”

“Andrew?” someone asks.

“Andrew Morton.” That causes enough of a stir that nervousness leaks into my bloodstream and makes my hands cold and clammy. Why is it that I feel that I said something terribly wrong?

“Are you and Andrew Morton friends?” someone else asks, and the question hits me in a sickening way. I name-dropped the grandson of the most powerful US Senator...the position my father is campaigning for. Sean is going to roast me alive.

“Yes. We’ve been friends for as long as I remember.” Friends, enemies, it’s all semantics at this point.

“Did you and Andrew Morton plan to attend the festival together?” Another reporter.

“Yes.”

“Were you on a date?” a woman asks.

My entire body recoils. “What?”

“Are you and Andrew Morton romantically involved?”

I become one of those bunnies who go still at the slightest sound. “I thought we were talking about Hendrix.”

“Did Mr. Pierce confront the men?”

Finally back on track. “No, he was adamant that there should be no violence.”

More questions and I put my hand in the air as I feel like I’m the one on trial. “Isn’t that the point? Hendrix went through my dad’s program, and one of the first chances he had to make a good decision, he made one. We’re strangers, and he helped me without violence. That, to me, is success.” A few people nod their heads, and because I don’t want to be done yet... “Mr. O’Bryan—grown men shouldn’t be following seventeen-year-old girls. I’m curious why you didn’t step in when I was being harassed. If you saw Hendrix and me together, then you know what happened, and it’s horrifying you didn’t help. Hendrix made the right choice. You did not.”

A rumble of conversation, Sean places a hand on my arm and gently, but firmly pushes me to the side. The raging fire in his eyes says he’s mentally measuring out the room in the basement he’s going to let me rot in for the next ten years.

My father approaches the microphone with an ease I envy. “Any more questions for Ellison can be sent to my press secretary. As you can tell, it’s been a trying day for my daughter, but we are most grateful for Mr. Pierce’s actions. We promised a program that was going to help our state’s youth turn their lives around, and, thanks to Mr. Pierce’s admirable actions, we are proud of our first program’s success.”

He offers Drix his hand again, and Drix accepts. Lots of pictures and applause, and Dad leans in and whispers something to him. I can’t tell what it is, but I do see the shadow that crosses over Drix’s face, his throat move as he swallows and then the slight nod of his head.