Полная версия

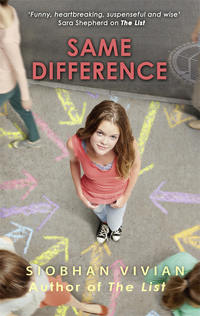

Same Difference

“They’re not going to bench you,” I grumble. Claire is the best player in middle school. She knows it, too. The high school coaches have come to see her play a few times. And her room is full of satiny ribbons stamped WINNER in gold and trophies, some so tall they have to sit on the floor.

“No one is going to be late,” Mom says, gunning through a yellow light in exactly the way my Driver’s Ed teacher told us not to. She eyes me in her rearview mirror. “But, Emily, you’re going to have to get up earlier from now on, so the rest of us aren’t in a panic every morning. That means no late nights before summer school.”

“It’s not summer school,” I say. “And I didn’t go anywhere last night.” Rick and Meg invited me out with them for pizza and then to Putt Putt Palace, but I didn’t feel like tagging along. I’m no good at sports. Neither is Meg, but without a boyfriend, there’s no one to laugh or tell me I’m cute when I swing and completely miss the golf ball. I just feel like I suck.

Mom shakes her head, disappointed. “Dad saw the light underneath your door after two in the morning, Emily.”

The thing was, I had a hard time falling asleep. I lay in bed for the longest time with my eyes closed and my television off, hoping it would happen. But it didn’t. So I got up and laid out my clothes for today on my club chair. That took about five seconds, because Meg and I had already discussed in detail what I should wear — my white capris, a tan and white striped cami, and a pair of pale gold leather skimmers that Meg let me borrow. I turned on my laptop, but no one else was online, so I shut it back down. I threw out some old makeup that I didn’t use anymore. And then, when I couldn’t think of anything else to do, I randomly decided to lay my new art supplies out on my floor in neat little piles.

A few weeks ago, Philadelphia College of Fine Art sent a list of materials that I’d need, like paint and brushes and charcoal and Strathmore drawing pads. It took Mom and me over an hour at Pearl to find everything.

When you’re a kid, colors have obvious names. Green is grass, red is cherry, and yellow is lemon. That changes when you grow out of markers that can be washed off the kitchen walls. How was I supposed to know that Sanguine is a fancy word for red? And what kind of purple was Dioxazine? It sounded like something I should have learned in Chemistry. Mars Black didn’t make much sense to me, either. Wasn’t Mars the Red Planet? It kind of freaked me out.

Mom felt bad for me, so she made this big show of buying the most expensive stuff they had, insisting that all my brushes be sable, and not the synthetic ones that are way cheaper. I didn’t complain because they were really nice, as soft as my makeup brushes from Bloomingdale’s.

I’d never owned real art supplies before, and seeing my whole floor covered in them felt luxurious. The materials in Ms. Kay’s classroom were old and gross. We only had big jugs of primary colors, like the ones a preschooler would finger paint with. And the brushes were frayed and fanned out and sometimes left strands behind in your strokes. We stopped using the clay because it was hard and flaky, even if you let it soak overnight inside a wet paper towel. I guess that’s why it felt like the possibilities of things I could do with my new supplies were limitless. It lit me up inside. I couldn’t sleep after touching everything. I was too excited for today.

“So all you’re going to do is art? Like, for the whole day?” Claire turns around in her seat. “That sounds kind of boring.”

Sometimes, it takes me a minute to recognize Claire as my sister. She’s tall, taller than all the boys in her class. Her hair is dark brown like my dad’s, and it’s a lot thicker than mine. She’s awkward now — a teenager’s body paired up with a kid’s face. But you can already tell that she’s going to be somebody when she gets to high school this fall. Maybe even as soon as her braces come off.

“Right, Claire. And running up and down a field a million times sounds so fun.”

“It is. And at least I’ll be with my friends. How are you going to survive a whole day away from Meg?”

Claire always makes jokes about how close Meg and I are, but it’s only because she doesn’t have a real best friend. She just has a big group of girls who she plays sports with.

“You’re just jealous. I heard you crying to Mom yesterday because I wouldn’t let you come swim with us. Maybe I’d let you if you weren’t so freaking annoying!”

Her face flushes deep red, like it does by the halftime of her soccer games. “Geez, Emily.” She turns back around and sinks low in her seat.

“Emily, be nice to your sister,” Mom scolds.

“She started it,” I say.

“But you’re older,” Mom says. “You’re supposed to be more mature.”

Whatever.

We turn into the parking lot of the Cherry Grove train station. It’s as crowded as the mall at Christmas.

“Just drop me off,” I say, unbuckling my seat belt.

“I want to make sure you’re on the right train,” she says, getting out with me.

I don’t understand why my mom thinks this is such a big deal. This won’t be the first time I’ve been to Philly — there have been plenty of family drives and school trips there. It’s just the first time I’ll be going alone.

The track that goes to Philadelphia is easy to find because everyone’s crowding together on it. The station doesn’t have any windows or service people there to buy tickets. The three automated ticket machines are completely surrounded.

“I’ve still got to buy a ticket!”

“Don’t worry. You can buy them on the train,” Mom says. “Do you have enough cash?”

“Yeah. And I’ve got my credit card, too.”

“What about your cell phone? Is it all charged up? Keep your wallet on you at all times. Don’t talk to strangers. You need to appear street-smart, so always walk with a purpose.” The train chugs into the station, and Mom yells over the noise. “And please don’t forget to call me when you get there.” Her bottom lip quivers.

I feel like such a baby. Luckily, no one pays me any attention, except to jostle me out of their way.

Everyone on the train is the same age as my parents. A few people watch with interest as I squish down the aisle with my big bags of art supplies. I feel confident, even a bit mysterious. I wonder if they wonder what I’m doing here all by myself.

It takes two cars before I find an empty seat. Well, it’s not exactly empty. A pair of super high heels pokes out of a black leather bag on the seat next to a lady in a business suit and spotless white running sneakers.

I wait a few seconds for the lady to notice me, but she never looks up from her newspaper. I’d keep searching, but my bags are heavy and the plastic handles are starting to rip. Finally I fake cough. The woman glances at me and grudgingly moves her bag to the floor so I can sit down.

A bell rings and “Tickets!” is shouted out in a rough, gravelly voice, like you’d expect in an old movie. The passengers slide their paper tickets into shallow pockets on the seats in front of them. I take out my wallet.

Eventually, a man steps up to my row. He’s got on a white button-up with a light gray tie, and his navy jacket is covered in brass buttons. I can’t see the hair on his head because of his cap, but his beard has a bunch of different shades of red and blond and white in it. “Where you going, miss?”

“Round-trip to Philadelphia,” I say proudly, and maybe a bit louder than necessary. And I hold out a crisp fifty-dollar bill.

He frowns and doesn’t take it. “I can’t break a fifty.”

“Oh, sorry.” I hand over a ten instead.

He still doesn’t take it. And he looks annoyed. “Your ticket’s thirteen dollars.”

“I thought tickets were ten,” I say, my voice squeaking so loud the man in front of me turns around to stare. That’s what I’d read on the transit website last night.

“There’s a three-dollar surcharge for buying on the train during peak hours,” he explains to me. “You need to use the ticket machines on the platform.”

I search through my change pocket, hoping for some quarters to make up the difference, but all I have are a few pennies and a dime. “Can I use my credit card?” I ask, yanking the silver square out of my wallet, dropping some receipts and my change on the floor.

The man laughs, not like I’ve said something funny, but because I’ve said something incredibly stupid. He points to his book of paper tickets and his hole puncher and shakes his head.

I panic. Are they going to make me get off the train at the next stop? I glance at the lady next to me. Maybe she’d help? Lend me three bucks? I’m obviously not some kind of homeless beggar. But her newspaper is a shield. She doesn’t want to see what’s going on.

The last thing in the world I want is to cry here and now, in front of all these people. I take a couple deep breaths.

The conductor looks at me, then quickly over each shoulder. “Listen,” he whispers, “just give me the ten and remember to buy your ticket on the platform next time.”

I thank him, but too quietly for him to hear, as I hand over the money. He punches a bunch of holes in my ticket, sending bits of yellow confetti cascading onto the floor.

I settle back into my seat with a deep exhale. The fake leather sticks to the skin on my back and it’s hard to get comfortable with my bags of supplies taking up all my legroom. The lady next to me drops her paper, gives me a flat smile, as if she were completely unaware of what happened right next to her a few seconds ago, and then flaps it open to another page.

I smile back, because what else am I going to do?

A few seconds later, my cell jingles. I think it might be Meg. But it’s my dad.

good luck today picasso

Dad is the only adult I know who can text. That’s how he and his secretary communicate while he’s showing real estate properties and taking bids. He was the one who filled all the homes in Blossom Manor, who sold Meg’s family their house. He also brought in the Starbucks and leased the stores in the strip mall across the highway. He’s the real estate king of Cherry Grove.

Thirty minutes later, the train rolls over the steely blue Ben Franklin Bridge, the gray water of the Delaware River splashing in white-capped waves below us. At the end of the bridge, there’s a huge sculpture of a lightning bolt crashing into an oversized metal key, which I guess represents Ben Franklin’s discovery of electricity. It’s like I’ve been struck by lightning, too, the way the hairs suddenly prickle up on my arms.

I am really doing this. It’s kind of funny, how far thirty miles can be. How much bigger than myself I feel already.

As we pull into the station, everyone stands up even though we can’t walk off the train yet. Someone behind me pushes into the small of my back with a briefcase. The train comes to a stop and everyone files out the small doors. I don’t really know where to go so I follow the flow of the masses up to the street.

I try to find the map that came with my orientation packet, but there are too many old school papers in my bag that I forgot to throw out. A huge clock behind me chimes 9:00 a.m. Orientation will be starting.

I take off and run . . . even though I’m still not sure if I’m going in the right direction.

Three

If you’re lost and trying to find an art school, you might as well forget about asking anyone who looks normal. Like moms pushing their babies in expensive-looking strollers, people in suits, groups of old ladies on their way to have brunch, or even police officers. That’s gotten me nothing but confused looks and indifferent shoulder shrugs, and now I’m twenty minutes late for orientation and completely disoriented. You can’t see for long distances when you’re lost in the middle of a city. There’s no horizon — just stacks of buildings interrupting your sight line. It’s like running through a maze with tall, tall walls.

I kneel down on the sidewalk and open up my bag to try to find something with the exact address printed on it. The salty smell of bacon drifts over and makes my stomach growl. I wish I hadn’t skipped breakfast.

I’m a couple feet away from a shiny metal food truck parked next to a fire hydrant. A few people are in line — two construction workers and an old lady with a dog. There’s also a very, very cute guy who’s watching me. He’s tall and lean, in a loose pair of dirty jeans and a VACATION RHODE ISLAND! tee that looks real . . . not like one you’d buy new in the mall. His hair locks in thick curls that look like rollatini pasta, and are almost the very same color of his skin — a rich, chocolaty brown.

I smile quickly at him and go back to looking through my papers. But as I shift my weight up off my knees and the rough pavement, the breeze catches the papers and a couple of them flutter out of my bag and into the air.

Luckily, the cute boy steps off the line and grabs them for me. He actually has to jump in the air for one, and his shirt lifts up from his waistband, revealing a very flat stomach, a stretch of gray elastic band from his Calvins, and a couple of star tattoos across his hip bones.

“I’m sorry,” I say, heated. “I made you lose your place in line.”

“No problem,” he says with a smile. “Coffee can wait.” But I’m not so sure. He looks half asleep, and a bit of toothpaste flakes off the left corner of his mouth. “Are you lost?”

“Is it that obvious?” I say, still digging frantically. “Ow!” My fingertip gets sliced on the edge of a paper. I squeeze the tip to stop the burn, and it bleeds a deep red drop.

“Maybe you just need coffee. I’m always lost without coffee.” He looks down at his sneakers. “Can I buy you a cup?”

It’s sweet how awkward he is. I can tell by his refusal to make eye contact and the worried look on his face that this is probably the first time he’s ever done something like this. And it’s painfully clear that it’s the first time I’ve ever been asked by a cute stranger if I want some coffee, since I’m so surprised by the question that my answer comes out as “Yes?”

“It’s okay if you’d rather have tea,” he says. “I mean, I’ll still want to buy you a cup if you prefer tea. Even if I don’t personally understand it.”

I personally don’t understand drinking a hot beverage on a humid summer morning, but I seriously doubt this silver cart makes anything close to a frozen peppermint mocha. Whatever. Suffering through a few sips will be totally worth it for this guy. “Coffee would be great,” I say. “Milk and sugar, please.”

He acts like he’s a waiter writing on a pad. “Milk and sugar, coming up.”

While he returns to the silver truck and my heart skips all over my body, I finally find my orientation packet. “Thank goodness!” I say, and when he returns with two steaming cups, I triumphantly show him the bunch of red papers with the words PHILADELPHIA COLLEGE OF FINE ART printed on them in a big bold font. “Can you tell me how to get here?”

“Oh, sorry!” The boy takes a step back, and suddenly notices the bags of art supplies at my feet. “You’re a summer student?” His eyebrows pop up, like that wasn’t at all what he was expecting. He is now very much awake.

I nod, though I don’t get what he has to be sorry for. “Do you know where the university is? I’m so late.” Then my cell phone rings loud in my bag. It’s a lame beeping version of Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” that Meg downloaded for me as a joke one time when I was in the bathroom. We’ve always laughed at it, but now, in front of this boy, it makes me feel incredibly lame.

I fumble to ignore the call. “My mom,” I tell him. I don’t know why. “She’s checking in on me. I think she’s nervous because I’m in the city all by myself.” And then I laugh, but it sounds so uncomfortable, I close my mouth and decide never to speak again.

“Interesting,” he says, with a teasing sort of grin. “No need to stress. It’s just around the corner on your left.”

He hands over my coffee, and I’m not sure what to do. I’d really love to stay. But I really have to go.

He makes up my mind for me.

“Maybe I’ll see you around sometime,” he says. “After all, you know where I get my coffee in the morning. That’s practically like knowing where I live.”

I point to the intersection. “I guess that makes us neighbors,” I say, and take off, grinning. A cute boy was just interested in me. That never, ever happens in Cherry Grove. People know each other too well there, so much so that surprises never really happen.

As soon as I step into the crosswalk and glance to my right, I see the Philadelphia College of Fine Art, all massive and stone and old like a castle, occupying almost an entire city block. It’s not what I imagined at all. When I had pictured a college, I thought about a big green lawn, kids outside playing Frisbee, a real campus. It’s a bit jarring, seeing it sandwiched between the sleek architecture of the surrounding silvery skyscrapers.

A bunch of signs lead the way through a set of red wooden doors. I have to push on them a couple times before they open into a huge atrium, with a glass ceiling and three levels of catwalks running along the sides.

The noise inside is deafening. High school kids are everywhere, bright flashes of color and personality, meandering from registration table to registration table, filling out permission slips, getting their temporary IDs laminated, picking up the keys to their dorm rooms, and not-so-subtly sizing each other up. Rows and rows of metal folding chairs are set up in the middle of the atrium, facing a low stage and podium. The seats are almost all filled.

A few older kids — students who are actually enrolled in this college, I guess — stare down from the catwalks, underneath a big WELCOME PRE-COLLEGE STUDENTS banner, and laugh at the whole crazy scene.

And it is crazy.

Two boys in striped shirts like Bert and Ernie are hugging and crying. They look like they are mid-good-bye. One boy fishes a red marker out of his pocket and draws a heart inside the other boy’s palm. It makes them both cry harder.

Next to them, a chubby Asian girl with blue-black hair, dressed in a high-neck beige lace dress that looks incredibly out of season for the last week of June, allows her mom to wipe some tomato-y lipstick from the corners of her mouth with a tissue while she taps away on her mini video game player.

A couple of feet ahead, a tall boy with an asymmetrical haircut and swollen acne awkwardly navigates the crowd toting three canvases — one under each arm and one strapped to his back. He swats people with the corners, unintentionally branding them with touches of wet pink paint.

I take small steps backward until I’m pressed against the wall. The place is crawling with the types of people you find huddled in groups of two or three at a typical high school. I don’t see anyone here who looks like me, and that feels strange. There are always people like me around. We are everywhere.

A hand squeezes my shoulder. It’s a slender lady wearing a white lab coat and carrying a clipboard marked STUDENT HEALTH SERVICES. She seems like a regular nurse, except for her orange Afro and the lei of hibiscus tattoos ringing her collarbone. “Sweetie, do you have your schedule and your ID? We’re about to get started.”

I shake my head. “I — my train — ”

“Do you know who your roommate is?”

“No. I mean, I’m a commuter. I’m not staying in the dorms.”

“Breathe. Breathe. Breathe,” she chants in a warm, friendly voice. “Come with me.”

I follow the nurse down through the crowds. She leads me to several tables, helps me get checked in, and fills my arms with even more papers and information. I’m glad she’s taking charge of the situation, because I can’t seem to concentrate on anything. There’s too much to look at.

There are way more kids here than I expected, at least two hundred total. Everyone seems to have at least one creative detail on them, something that shows that they belong here. I’m plain by comparison. It’s embarrassing, how much effort it took for me to wear something that looks exactly like a blank piece of paper. No wonder no one makes eye contact with me.

Though it’s not like the other students are mingling all that much, either. Everyone seems cautious and careful around each other. The only people who are enjoying themselves are the parents. They talk and laugh in little groups, an Aha! look on their faces, like suddenly, in this context, their weird kids make sense.

“Please take a seat, everyone, and we’ll get you off to classes as soon as possible,” a low female voice booms out of a microphone I can’t see from where I’m standing.

“What’s your name?” a boy asks me from behind a table. He’s wearing a T-shirt that says STAFF, and his black hair pokes out like carpet fringe from underneath a plaid yarmulke, covered in crudely sewn yellow lightning bolt patches.

“Emily Thompson.” A flashbulb pops in my face.

He thumbs through a file box. “Okay, here’s your schedule, Emily. And here’s your ID.” He hands me a stack of papers and a warm, plastic square. My eyes are closed in the picture, like I’m sleeping. “Go ahead and find a seat.”

There are not many empty chairs. The ones that are vacant seem uncomfortably sandwiched between people who lean across them to whisper to each other. I get a hollow feeling in my chest. If I had gotten here earlier, maybe I would have met some people already.

Maybe.

I walk toward the back of the atrium and take the very last chair in the row. The section reserved for parents.

A short woman with stringy black hair and burgundy lipstick stands behind the podium on the stage. She beams a smile out into the crowd. Even from this distance, her teeth look gray and dull, like she is definitely a smoker. Of cigars.

“Hello, students. My name is Dr. Tobin, and I am the Program Director of the Pre-College Summer Art Institute. I want to welcome you to Philadelphia and to six weeks filled with personal growth and artistic discovery!” She’s leaning in too close to the microphone, and her deep voice vibrates along my metal chair. “I want to begin by going over the housing rules for the summer for those of you staying in the dorms.”

The funny thing is, there are very few rules for her to go over. Obviously, no drugs or alcohol are allowed, but students who live in the dorms can come and go from the campus as they please until 1:00 a.m., when curfew begins. It sounds pretty good, considering the new strict summer curfew Mom’s imposed.

I actually considered living on campus when Ms. Kay first gave me the brochure, but now I’m glad I decided against it. The dorms don’t have air-conditioning, and the beds are probably not nearly as comfortable as mine. And what would I actually do here all by myself at night? I’d miss home too much.

Dr. Tobin asks everyone to look at their schedules. Mine is damp and wrinkled from being squeezed in my hand. I have Drawing on Tuesdays and Mixed Media on Thursdays. Those were my first-choice classes, which is pretty nice.

“Classes will run from nine until four-thirty Tuesdays and Thursdays. Wednesdays are reserved for program-wide field trips to museums and creative destinations all over the city. Everyone will be assigned designated studio space where you can store your supplies, and you should feel free to use the campus on non-program days to continue working on your projects.”

I’m relieved to hear we get studio space, because the muscle between my shoulder blades is throbbing from carrying all my bags and I definitely don’t want to lug this stuff in for every class. But I doubt I’ll be coming into Philadelphia on the days I don’t have class.

“Finally, the summer program will culminate in a gallery reception, where student work will be displayed for faculty, friends, and family. There will be a special section where the best student work will be displayed, juried by faculty consensus.” Dr. Tobin clears her throat dramatically. “But I want to remind you all that art is not about competition. It’s about self-expression and discovery. I hope you will allow yourself the opportunity to explore your own creativity, to strip yourself of the hesitations and insecurities that might have limited you in your high school, and create in an environment free of judgments and established social mores. Here, you are among your true peers, people who value originality.”