Полная версия

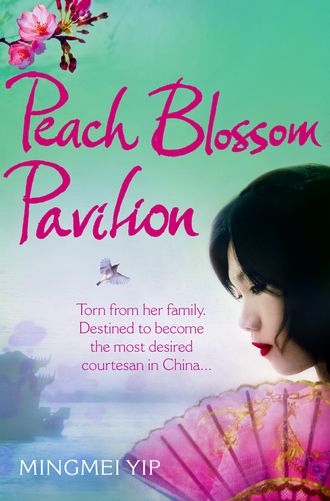

Peach Blossom Pavilion

That night, I could not sleep at all because my mind kept spinning with the image of Spring Moon.

The next day, as soon as it became light, I went to knock at Pearl’s door and heard her tell me to come in.

Wearing a high-collared gown embroidered with gold-threaded peonies, she was standing beside the large blue-and-white bowl, feeding her goldfish.

I walked up to her. ‘Sister Pearl, have you heard anything about Spring Moon?’

‘She’s in the dark room.’ Not looking at me, Pearl continued to throw morsels of bread into the bowl.

We silently watched the fish swim and wag their tails for a while before she motioned me to sit on the sofa.

It seemed strange to be resting my bottom on the soft velvet cushion while Spring Moon was down there. Creepy sensations crawled all over my body. ‘But she’s wounded, why did they put her there?’

‘Because she offended the police chief. Nobody can afford to do that. If you do, you’re asking for a bullet in your head. She’s lucky that she’s now only lying in the dark room, not in a grave.’

‘You think she’ll die?’

‘You think Mama, after she’s made her investment, will let her daughters die so easily? Of course not, because any living daughter is better than a dead one. Once dead, all her investment will be thrown into the chamber pot. But a living daughter … even if she’s disfigured, Mama can still sell her to a cheap whorehouse and get some money back, even if just a few coins.’ She paused, then, ‘Anyway, her wound was not serious.’ She sighed, ‘The dark room is to teach any disobedient girl a lesson.’

Some silence passed before Pearl spoke again. ‘Let’s not talk about unpleasant things.’ She stood up, went to the luohan bed, and from underneath it took out an elongated object in a brocade cover. She removed the case and carefully put the object onto the table.

I studied it for long moments before I asked, ‘What is this?’

‘It’s a qin – seven-stringed zither,’ she said softly, running her fingers along its length.

The wooden surface, lacquered and decorated with dots of mother-of-pearl, shone with a lovely lustre.

‘So are we going to play this today?’

Pearl chuckled. ‘Ah, silly girl, you think you can just learn how to play this instrument in a day? It takes years and years of hard work.’

She went on, her voice filled with emotion, ‘I want to play you a piece. It’s called “Remembering an Old Friend.”’

I asked tentatively, ‘Is it … Spring Moon?’

‘No, but my elder sister. Spring Moon is naïve like her.’

‘Where is your sister now?’

Pearl didn’t answer my question. The sadness on her face suppressed my urge to further enquire. So I changed the subject. ‘Sister Pearl, do you know how Spring Moon ended up here in Peach Blossom?’

Pearl smoothed the brocade cover and sighed, ‘Her father was a well-off ship merchant. One time when he was shipping some precious goods from Shanghai to Hong Kong, a storm struck and destroyed everything – the goods, the ship, the sailors, and himself. So her family lost everything overnight, literally. Not only that, since they hadn’t bought insurance, they had to pay for all the losses, including the goods to be delivered to Hong Kong and the compensation to the sailors’ widows. After the father’s costly funeral, there was nothing left. So her father’s concubines sold her here to pay their debts.

‘Spring Moon was thrown overnight from atop the clouds to the ground. She was used to having maids serve her, and now she is bossed around. I was told she had a really nice and handsome fiancé. So of course it revolted her to be molested by that disgusting police chief. Poor girl, that was her first day out, and she’s already caused this big trouble.’

Pearl put away the qin, then took the pot and poured us both tea. We sipped in silence.

Then I asked, ‘I don’t understand why Spring Moon kept staring at me from behind the bamboo grove.’

Pearl looked me in the eyes. ‘She’s envious of your beauty, especially those dimples of yours.’

‘She told you that?’

‘No. But I can tell. I always catch her squeezing in her cheeks to have the illusion of dimples.’ Pearl sighed. ‘Hai, poor girl. She still doesn’t have to sleep with customers. When she does, there’ll be more …’

‘More what?’

‘Nothing.’

Moments passed. Pearl once again slid the qin out from its brocade cover and started to tune it. The seven strings, lightly touched, emitted soft, subtle sounds as if they were whispering the secrets of heaven. When Pearl had finished tuning, she meditated for seconds, then began to play. The melodies seemed to tell a very sad tale. Mesmerised, I imagined waves of melancholy sloshing gently through the room, caressing our wounded hearts.

I also noticed something unexpected – the transformation of Pearl’s face. During her pipa playing when she vigorously plucked the strings, she always looked animated and flirtatious. Her long hair would fall over her face and tremble like dark waves and her eyes would give out sparks like twinkling stars. But as she played the qin, her countenance composed itself into that of a scholar’s – serious, serene, respectful. The fingers that pulled and plucked aggressively on the pipa now effortlessly glided and pirouetted, like dragonflies skipping over a brook, swallows touching water, or petals falling on waves.

My mind was lifted away by Pearl’s elegant playing to a quiet, far-off place where I could almost see Baba sitting under a shaded bamboo grove, playing a sad tune from his fiddle and smiling wryly at me.

After she finished, we sighed simultaneously. I felt sorry that such wonderful music had to end.

‘Sister Pearl.’ I searched her eyes. ‘The qin sounds so beautiful—’

She stared at me curiously. ‘You find this music beautiful?’

Eagerly I nodded.

‘You’re very gifted, Xiang Xiang. Not many young girls have the insight to appreciate qin melodies—’

‘Can you teach me how to play the qin?’

Her face darkened. ‘No.’

‘But … why not?’ I felt both surprised and hurt by her refusal.

‘Because I think you should concentrate on the pipa.’ Before I could protest, she went on, ‘Xiang Xiang, the qin won’t make you famous and popular, but the pipa will.’

‘Why? And how?’

‘Because the pipa’s tone is short and its music tuneful. You can attract the customers’ attention right away. But it’ll take years of cultivation just to appreciate the qin, let alone to play it, and play it well. As women, we have only very limited years of youth and beauty. So by the time you’ve mastered the instrument, you’ve already lost both. Worse still, hardly any customers will be cultured enough to appreciate the qin – or your talent.’

‘Sister Pearl,’ I searched her smooth, beautiful face, ‘but you’ve neither lost your youth nor beauty …’

‘Because I’m exceptional.’

I wanted to say that I, too, was exceptional.

But she’d already taken a handkerchief and begun to wipe the instrument, as tenderly as if it were her lover. After that, she said ‘Now I’ll play “Lament Behind the Long Gate.”’

‘What is it about?’

‘The misery of an ill-fated woman.’

6

A Lucky Day

It had been ten months since I’d arrived at Peach Blossom Pavilion yet I still hadn’t received any letter from Mother. First I was angry at her – how could she have forgotten her only daughter? Then I began to worry – had anything happened to her? Those bald-headed old maids in the nunnery, what had they done to my mother? It pained me to think of Mother, her head shaved and her slender body hidden underneath a dreary grey robe, with nothing to do all day but mumble texts from yellowing sutras that no one could understand anyway.

I wanted both my mother and her hair back!

Every night after I finished work, I’d take off the Guan Yin pendant Mother had put around my neck, hold it in front of me, and ask the Goddess to protect her – wherever she was now – and remind her to write me.

Now my only comfort was Guigui. Fed with all the delicacies, not only did he grow bigger each day, he also looked cuter. I began to teach him different tricks – carrying things, kneeling, hand-shaking, kowtowing. He was so chubby with his fluffy yellow fur that sometimes he looked like a moon rolling on earth. Whenever he’d given a good show, I’d take him to the kitchen and feed him with more goodies. To repay my generosity (at the customers’ expense), Guigui would tilt his fat head to stare at me curiously, then lick all over my face. He was so cute and affectionate that even when he misbehaved, I had no heart to punish him. One time he peed right under the altar where the White-Browed God was worshipped. I felt so scared that I almost flung him out of the altar room, then frantically wiped the mess clean. The White-Browed God was Peach Blossom Pavilion’s most revered deity – to lure in an endless flow of money and keep the wealthy guests bewitched by the sisters. If Mama had seen the puppy pee right beneath the Money God, she’d have beaten him – and maybe me – severely.

When I was about to scold Guigui, he dropped his head and whimpered, peering at me with big, soulful eyes. So, instead of spanking him hard on his little bottom, I scooped him up and threw him in the air!

Guigui and I became inseparable. When I prayed to Guan Yin, besides my mother, I now included him when asking for the goddess’s protection.

One afternoon, my heart burdened with Mother’s situation, I slipped into Pearl’s room. She was reclining on the sofa, reading a magazine. I watched as she picked up red-dyed watermelon seeds, splitting each between her teeth with a sensuous pop. Then her small tongue would, like a lizard snatching its prey, draw out the egg-shaped flesh into her mouth.

When I stepped across the threshold, she spat out a husk into a celadon bowl, looked up at me, and smiled. ‘Xiang Xiang, shouldn’t you be practising your arts in your room?’

‘Sister Pearl, can you do me a favour?’

‘Come sit with me.’ She put down her magazine. ‘What is it that you want?’

‘To hear you play “Remembering an Old Friend” on the qin.’

‘Why? You have someone to remember?’

‘My mother. I miss her,’ I said, feeling tears stinging my eyes.

Pearl scrutinised me for long moments, then glanced at the clock. ‘All right, I still have some time before my guest arrives.’

She stood up and went to take the qin from underneath her bed. Carefully she peeled off the brocade cover, laid the instrument on the table, burned incense, then tuned the seven strings. After that, she began to play. Again, I was entranced, not only by the music, but also by the movements of her fingers, as graceful as clouds drifting across the sky. Listening to the melodies pour out from her tapered fingers, all my worries seemed to vanish.

When Pearl finished, again I begged her to teach me to play the qin. Again, she refused.

‘Please, Sister Pearl,’ I could hear the urgency in my voice, ‘I only want to learn “Remembering an Old Friend,” so I can play it and think of my mother.’

She didn’t reply, but looked down to study the floral patterns of her skirt.

‘Please, Sister Pearl, just one piece.’

Now she looked up to study me.

‘Just one.’ I raised one finger and pleaded incessantly until her face broke into a smile like the blossoming chrysanthemums on her jacket.

‘All right, you little witch. But Xiang Xiang, promise me you’ll keep this a secret between us. Can you do that?’

I nodded my head like a hungry woodpecker.

‘All right, now go back to your room and wash yourself thoroughly.’

‘Sister Pearl, but you’ve just promised to teach me to play the qin!’

‘Bathing yourself is part of the ritual of playing. After that, you have to burn incense to cleanse the air and meditate to purify your mind, before you can even touch the instrument. Never forget that when you play the qin, you’re not just making music, but communicating with the deepest mysteries of heaven.’

I was too surprised to respond; she went on, ‘I told you it’s hard. Do you still want to learn?’

‘Yes, Sister Pearl!’

‘Good, I like your determination.’ She cast me a sharp glance. ‘In the past, a student had to live with her teacher and wait upon her for two years – preparing tea, cooking, cleaning the house, massaging her sore muscles – before there’d even be any mention of lessons. You’re lucky that I exempt you from all these. Now go to wash!’

‘Thank you, Sister Pearl,’ I yelled, then dashed toward the door.

She called out at my back, ‘Remember, this instrument is sacred. And don’t forget your pipa either.’

I turned around. ‘Sister Pearl, I won’t.’

‘Come back and I’ll teach you how to tune the qin – as well as your mind.’

So from that day on I was secretly learning to play this venerated instrument. At the start of each lesson, I’d meticulously tune the seven silk strings, while stealing glances at Pearl and wishing I could look as beautiful and play as elegantly. I would practise until my fingers bled and grew calloused, and my shoulders felt stiff and sore. But strangely, my heart was filled with joy at the sad tunes of the qin.

Needless to say, I dared not forget singing, painting, nor playing my pipa. Pearl warned me again and again if I didn’t learn the other arts well, she’d stop teaching me the qin. But her worry was unnecessary, for I was good at all my lessons! Mr. Wu, the painting teacher, was so pleased with my talent that he showered me with gifts – brushes of all sizes, ink stones engraved with scenes of the four seasons, rice paper sprinkled with simulated gold flakes. He also praised my poems, telling me that some were so good that they could be used as opera lyrics. He predicted that I’d be famous soon, very soon. Mr. Ma, the opera teacher, said I had a voice like a lark’s, which possessed the charm to entice the sun to rise and cajole it to set. But he also flattered me by continuing to accidentally brush his hand all over my body.

Word about my talents began to spread. Some customers asked to look at my paintings. Some halted by my door to listen to my singing. Others sighed with pleasure when they had a chance to glimpse my fingers performing acrobatics on the pipa. My poems were passed around and discussed as if they were works by Li Bai or Du Fu.

One afternoon while I was practising ‘Spring Moonlight over the River’ on the pipa, Fang Rong burst into my room. She dropped onto the chair, breathing heavily while eyeing me happily. She studied me so hard and so long that I felt colour rise in my cheeks.

‘What is it, Mama?’ I asked, putting down my instrument.

She shot up from the chair and went to the mirror, motioning me to follow her.

Our reflections stared back at us from the polished surface. Mama smiled mischievously, cocking an eye at me. ‘Xiang Xiang, less than a year living in Peach Blossom, see what a lovely girl I’ve made of you.’

I looked at my own image for long moments, and for the first time I agreed with her. But I felt embarrassed to say yes, so I remained silent.

She lifted and tousled my hair. ‘But you know what? Today you’ll look even prettier, for I’m taking you out to have your hair styled!’

I turned to stare at her. ‘Styled?’

‘Yes, most girls have never even heard of it, let alone have the money to have it done. So lucky you!’

But I had heard of it. ‘You mean like … those stars in a movie?’ Of course I’d never seen ‘those stars’ in a real movie, only in newspapers and magazines Baba had brought home from the warlord’s house.

‘Exactly! Do you want to look like a movie star?’

I turned back to look at the mirror and saw my head nodding like that of a childless woman kowtowing to Guan Yin for a baby boy.

It was a hot, sunny Friday afternoon. Besides me, Fang Rong also took two other girls to have their hair styled. One, voluptuous and very silly acting, was called Jade Vase, and the other, to my surprise, was Spring Moon. I was glad that Mama had arranged for Spring Moon to share the rickshaw with me while she shared hers with Jade Vase. Spring Moon seemed to have recovered from that horrible night and the scar on her arm turned out to be quite small. Now, I’d finally have the chance to discuss with her in detail the strong stench and scurrying rats of the dark room – and maybe even fuck. But we ended up gawking at the rarely glimpsed city life outside the turquoise pavilion. Our eyes couldn’t detach themselves from busy Nanking Boulevard with its famous red-and-gold signboards. Our fingers kept thrusting here and there to point out remembered sights.

Spring Moon pointed at a grand building and said proudly in her high-pitched voice, ‘Look, that’s Xing Xing Department Store where I used to shop with my parents.’

I craned my neck and saw three Western-dressed tai tai studying merchandise with great intensity. Behind them shuffled amahs burdened with overflowing shopping bags.

While my eyes were appreciating the society ladies’ elaborate make-up and brocade dresses, Spring Moon’s finger had already shifted to an even grander building next to Xing Xing, her voice climbing higher and higher in the air. ‘Look, this is Sincere Department Store. My father once bought me a gold necklace in the jewellery department on the third floor!’

She plunged on excitedly, ‘My father also used to take me to the Heavenly Tune Pavilion open-air café on the top floor of the Wing On Department Store. There, I could see the whole city, including the China Peace Company, the International Hotel, and the race track!’

When the speeding rickshaw had left the two stores and the three tai tai behind, a silence fell between us.

To leave her to her thoughts, I turned to take in the scenes on the street.

A vendor, with two baskets in front, yelled at the top of his voice, ‘Fresh and aromatic roasted chicken! Your money back if it’s not aromatic!’

Next to him an elderly woman, kneeling, begged by knocking her head loudly on the ground.

A noodle seller, bare-chested and leathery-faced, was banging a brass gong to attract attention.

Under the scorching sun, a red-turbanned, black-bearded Indian policeman frantically wielded a baton to direct traffic. Sweat poured down his dark face like black bean sauce.

Then I spotted two small children followed by doting parents swarm into a candy store. When I saw the big smiles on the parents’ faces, my heart was seized with grief mixed with bitterness. Since the first day I’d been taken to Peach Blossom, despite the fact that I had a mother, plus another set of ‘parents’ unexpectedly dropped onto my lap, I still felt orphaned. I poked my head out of the rickshaw so that Spring Moon wouldn’t see the tears streaming down my cheeks.

Just then her voice rose next to my ear, startling me. ‘See, Xiang Xiang, that’s Mali Pig For!’

I wiped my tears while craning my neck. ‘Who?’

‘The famous Hollywood movie star! Over there, on the signboard of the Peking Theatre!’

Now I saw the picture showing the huge head of a foreign woman with wavy hair and a dreamy look. Next to her were several English words that I tried but failed to read. I turned to Spring Moon. ‘Can you read those chicken’s intestines?’

She smiled proudly. ‘Of course.’ Then, her lips pouted like a chicken’s ass, she began to read. ‘Poor Little Rich Girl.’

‘Wah! Where did you learn English?’

‘My father used to hire a private tutor to teach us.’ A pause, then she asked regally, ‘Xiang Xiang, have you ever seen a movie?’

Pathetically I shook my head.

A smile bloomed on her face. ‘My father used to take me to all the movie theatres: the Peking, the Embassy, and the Lyceum. If you have a chance to go inside these places, I bet you’ll be impressed. They’re like palaces!’

Spring Moon’s eyes turned red. I looked away into the distance across the harbour behind the hazy skyline. A ship was blowing its whistle as it passed another. Like a pair of scissors, a third ship slid soundlessly through the sapphire waves, its American flag fluttering in the breeze like a brightly coloured dress.

America! I muttered to myself. I hoped someday I’d be able to leave Shanghai to see the world, places such as America where I could meet this famous, strange woman called Mali Pig For.

Two rickshaws sped past ours; the coolies’ bare feet kicked up clouds of dust.

Everything outside Peach Blossom was so real, so lively … and yet illusory. Life seemed a deep, confused dream.

When I was about to turn back to talk to Spring Moon, the rickshaw suddenly pulled to a stop, jolting us forward. Fang Rong paid the two heavily sweating coolies, then, with an imperious air, led us into the hairstyling establishment.

The walls of the shop were covered with mirrors, giving it a spacious, mysterious look. Pasted on the mirrors were pictures of Chinese movie stars; all had shiny, styled hair like black waves gleaming under the moon.

Upon seeing us, several men, white towels draped over their arms, hurried to greet Fang Rong. They smiled obsequiously at her but scrutinised us like wolves. After we sat down, Mama told them to fix each of us a different hairdo.

She thrust a pudgy finger at Jade Vase. ‘She has an ugly mole on her forehead, so give her the weeping willow fringe to hide it.’ Then she motioned to Spring Moon. ‘Her face’s too round and her forehead too low, so give her the one-line fringe to cover everything.’ Finally she turned to me, smiling generously. ‘This one’s lucky; she’ll get the glamorous star-studded sky.’

Wah! I almost burst into happy laughter. Star-studded sky! But I had no time to relish this honor, for the three hairstylists, smiling knowingly, had already begun to muss our hair with expertly moving fingers.

It took more than an hour for the three men to cut, wash, and style our hair. We looked at each other in the mirror and discovered that Jade Vase’s forehead was covered by a narrow patch of soft hair hung low like weeping willow branches. Spring Moon’s face was framed with a thick fringe and straight hair down the sides, which magically made her round face look slender. For myself, I was pleased to see my hair pulled backward to reveal my much-envied high forehead and melon-seed face. Moreover, my three-thousand-threads-of-trouble were decorated with a gold clasp blossoming with pearls! My face seemed to have changed. Suddenly it looked glamorous … as if I were a real movie star who’d dance with swirling dress to dreamy music in a grand ballroom hung with glittering chandeliers!

A sob woke me from my intoxication; I turned and caught Spring Moon’s gaze. Her teary eyes lingered on my face like a cat pathetically pawing a fish bone.

‘Spring Moon,’ I took a deep breath, ‘why—’

Mama’s coarse voice roared in the air. ‘Spring Moon, stop that! Don’t envy the others. You should be grateful not only that you’re still alive, but that you’re alive with styled hair and a slender face, instead of one that looks like a puffed bun!’

Spring Moon shut up at once. After that, Mama quickly paid and led us out of the shop. This time she didn’t hail rickshaws. To my amazement, she led us along the busiest section of Nanking Boulevard, where our rickshaws had passed earlier! More surprises came when she led us into a fabric store and announced, ‘Pick what you like and I’ll have them tailored into Chinese gowns and Western dresses for all three of you.’

These generous words pouring from her mouth now sounded to me as enchanting as qin music! Holding bolts of floral satin against my skin, I felt weak with happiness. Jade Vase oohed and aahed and aii-ya-ed while her fingers ran over rolls of silk that cascaded before us like rainbowed waterfalls. Even Spring Moon’s sad, watery eyes now sparkled.