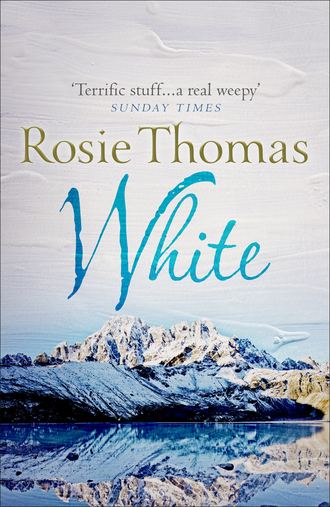

White

Полная версия

White

Жанр: книги по психологиизарубежные любовные романысовременная зарубежная литературазарубежная психология

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2018

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу