Полная версия

Unbroken

Anthony Zamperini was at his wits’ end. The police always seemed to be on the front porch, trying to talk sense into Louie. There were neighbors to be apologized to and damages to be compensated for with money that Anthony couldn’t spare. Adoring his son but exasperated by his behavior, Anthony delivered frequent, forceful spankings. Once, after he’d caught Louie wiggling through a window in the middle of the night, he delivered a kick to the rear so forceful that it lifted Louie off the floor. Louie absorbed the punishment in tearless silence, then committed the same crimes again, just to show he could.

Louie’s mother, Louise, took a different tack. Louie was a copy of herself, right down to the vivid blue eyes. When pushed, she shoved; sold a bad cut of meat, she’d march down to the butcher, frying pan in hand. Loving mischief, she spread icing over a cardboard box and presented it as a birthday cake to a neighbor, who promptly got the knife stuck. When Pete told her he’d drink his castor oil if she gave him a box of candy, she agreed, watched him drink it, then handed him an empty candy box. “You only asked for the box, honey,” she said with a smile. “That’s all I got.” And she understood Louie’s restiveness. One Halloween, she dressed as a boy and raced around town trick-or-treating with Louie and Pete. A gang of kids, thinking she was one of the local toughs, tackled her and tried to steal her pants. Little Louise Zamperini, mother of four, was deep in the melee when the cops picked her up for brawling.

Knowing that punishing Louie would only provoke his defiance, Louise took a surreptitious route toward reforming him. In search of an informant, she worked over Louie’s schoolmates with homemade pie and turned up a soft boy named Hugh, whose sweet tooth was Louie’s undoing. Louise suddenly knew everything Louie was up to, and her children wondered if she had developed psychic powers. Sure that Sylvia was snitching, Louie refused to sit at the supper table with her, eating his meals in spiteful solitude off the open oven door. He once became so enraged with her that he chased her around the block. Outrunning Louie for the only time in her life, Sylvia cut down the alley and dove into her father’s work shed. Louie flushed her out by feeding his three-foot-long pet snake into the crawl space. She then locked herself in the family car and didn’t come out for an entire afternoon. “It was a matter of life and death,” she said some seventy-five years later.

For all her efforts, Louise couldn’t change Louie. He ran away and wandered around San Diego for days, sleeping under a highway overpass. He tried to ride a steer in a pasture, got tossed onto the ragged edge of a fallen tree, and limped home with his gashed knee bound in a handkerchief. Twenty-seven stitches didn’t tame him. He hit one kid so hard that he broke his nose. He upended another boy and stuffed paper towels in his mouth. Parents forbade their kids from going near him. A farmer, furious over Louie’s robberies, loaded his shotgun with rock salt and blasted him in the tail. Louie beat one kid so badly, leaving him unconscious in a ditch, that he was afraid he’d killed him. When Louise saw the blood on Louie’s fists, she burst into tears.

As Louie prepared to start Torrance High, he was looking less like an impish kid and more like a dangerous young man. High school would be the end of his education. There was no money for college; Anthony’s paycheck ran out before the week’s end, forcing Louise to improvise meals out of eggplant, milk, stale bread, wild mushrooms, and rabbits that Louie and Pete shot in the fields. With flunking grades and no skills, Louie had no chance for a scholarship. It was unlikely that he could land a job. The Depression had come, and the unemployment rate was nearing 25 percent. Louie had no real ambitions. If asked what he wanted to be, his answer would have been “cowboy.”

In the 1930s, America was infatuated with the pseudoscience of eugenics and its promise of strengthening the human race by culling the “unfit” from the genetic pool. Along with the “feebleminded,” insane, and criminal, those so classified included women who had sex out of wedlock (considered a mental illness), orphans, the disabled, the poor, the homeless, epileptics, masturbators, the blind and the deaf, alcoholics, and girls whose genitals exceeded certain measurements. Some eugenicists advocated euthanasia, and in mental hospitals, this was quietly carried out on scores of people through “lethal neglect” or outright murder. At one Illinois mental hospital, new patients were dosed with milk from cows infected with tuberculosis, in the belief that only the undesirable would perish. As many as four in ten of these patients died. A more popular tool of eugenics was forced sterilization, employed on a raft of lost souls who, through misbehavior or misfortune, fell into the hands of state governments. By 1930, when Louie was entering his teens, California was enraptured with eugenics, and would ultimately sterilize some twenty thousand people.

When Louie was in his early teens, an event in Torrance brought reality home. A kid from Louie’s neighborhood was deemed feebleminded, institutionalized, and barely saved from sterilization through a frantic legal effort by his parents, funded by their Torrance neighbors. Tutored by Louie’s siblings, the boy earned straight A’s. Louie was never more than an inch from juvenile hall or jail, and as a serial troublemaker, a failing student, and a suspect Italian, he was just the sort of rogue that eugenicists wanted to cull. Suddenly understanding what he was risking, he felt deeply shaken.

The person that Louie had become was not, he knew, his authentic self. He made hesitant efforts to connect to others. He scrubbed the kitchen floor to surprise his mother, but she assumed that Pete had done it. While his father was out of town, Louie overhauled the engine on the family’s Marmon Roosevelt Straight-8 sedan. He baked biscuits and gave them away; when his mother, tired of the mess, booted him from her kitchen, he resumed baking in a neighbor’s house. He doled out nearly everything he stole. He was “bighearted,” said Pete. “Louie would give away anything, whether it was his or not.”

Each attempt he made to right himself ended wrong. He holed up alone, reading Zane Grey novels and wishing himself into them, a man and his horse on the frontier, broken off from the world. He haunted the theater for western movies, losing track of the plots while he stared at the scenery. On some nights, he’d drag his bedding into the yard to sleep alone. On others, he’d lie awake in bed, beneath pinups of movie cowboy Tom Mix and his wonder horse, Tony, feeling snared on something from which he couldn’t kick free.

In the back bedroom he could hear trains passing. Lying beside his sleeping brother, he’d listen to the broad, low sound: faint, then rising, faint again, then a high, beckoning whistle, then gone. The sound of it brought goose bumps. Lost in longing, Louie imagined himself on a train, rolling into country he couldn’t see, growing smaller and more distant until he disappeared.

Two Run Like Mad

THE REHABILITATION OF LOUIE ZAMPERINI BEGAN IN 1931, with a key. Fourteen-year-old Louie was in a locksmith shop when he heard someone say that if you put any key in any lock, it has a one-in-fifty chance of fitting. Inspired, Louie began collecting keys and trying locks. He had no luck until he tried his house key on the back door of the Torrance High gym. When basketball season began, there was an inexplicable discrepancy between the number of ten-cent tickets sold and the considerably larger number of kids in the bleachers. In late 1931, someone caught on, and Louie was hauled to the principal’s office for the umpteenth time. In California, winter-born students entered new grades in January, so Louie was about to start ninth grade. The principal punished him by making him ineligible for athletic and social activities. Louie, who never joined anything, was indifferent.

When Pete learned what had happened, he headed straight to the principal’s office. Though his mother didn’t yet speak much English, he towed her along to give his presentation weight. He told the principal that Louie craved attention but had never won it in the form of praise, so he sought it in the form of punishment. If Louie were recognized for doing something right, Pete argued, he’d turn his life around. He asked the principal to allow Louie to join a sport. When the principal balked, Pete asked him if he could live with allowing Louie to fail. It was a cheeky thing for a sixteen-year-old to say to his principal, but Pete was the one kid in Torrance who could get away with such a remark, and make it persuasive. Louie was made eligible for athletics for 1932.

Pete had big plans for Louie. A senior in 1931–32, he would graduate with ten varsity letters, including three in basketball and three in baseball. But it was track, in which he earned four varsity letters, tied the school half-mile record, and set its mile record of 5:06, that was his true forte. Looking at Louie, whose getaway speed was his saving grace, Pete thought he saw the same incipient talent.

As it turned out, it wasn’t Pete who got Louie onto a track for the first time. It was Louie’s weakness for girls. In February, the ninth-grade girls began assembling a team for an interclass track meet, and in a class with only four boys, Louie was the only male who looked like he could run. The girls worked their charms, and Louie found himself standing on the track, barefoot, for a 660-yard race. When everyone ran, he followed, churning along with jimmying elbows and dropping far behind. As he labored home last, he heard tittering. Gasping and humiliated, he ran straight off the track and hid under the bleachers. The coach muttered something about how that kid belonged anywhere but in a footrace. “He’s my brother,” Pete replied.

From that day on, Pete was all over Louie, forcing him to train, then dragging him to the track to run in a second meet. Urged on by kids in the stands, Louie put in just enough effort to beat one boy and finish third. He hated running, but the applause was intoxicating, and the prospect of more was just enough incentive to keep him marginally compliant. Pete herded him out to train every day and rode his bicycle behind him, whacking him with a stick. Louie dragged his feet, bellyached, and quit at the first sign of fatigue. Pete made him get up and keep going. Louie started winning. At the season’s end, he became the first Torrance kid to make the All City Finals. He finished fifth.

Pete had been right about Louie’s talent. But to Louie, training felt like one more constraint. At night he listened to the whistles of passing trains, and one day in the summer of ‘32, he couldn’t bear it any longer.

It began over a chore that Louie’s father asked him to do. Louie resisted, a spat ensued, and Louie threw some clothes into a bag and stormed toward the front door. His parents ordered him to stay; Louie was beyond persuasion. As he walked out, his mother rushed to the kitchen and emerged with a sandwich wrapped in waxed paper. Louie stuffed it in his bag and left. He was partway down the front walk when he heard his name called. When he turned, there was his father, grim-faced, holding two dollars in his outstretched hand. It was a lot of money for a man whose paycheck didn’t bridge the week. Louie took it and walked away.

He rounded up a friend, and together they hitchhiked to Los Angeles, broke into a car, and slept on the seats. The next day they jumped a train, climbed onto the roof, and rode north.

The trip was a nightmare. The boys got locked in a boxcar so hot that they were soon frantic to escape. Louie found a discarded strip of metal, climbed on his friend’s shoulders, pried a vent open, squirmed out, and helped his friend out, badly cutting himself in the process. Then they were discovered by the railroad detective, who forced them to jump from the moving train at gunpoint. After several days of walking, getting chased out of orchards and grocery stores where they tried to steal food, they wound up sitting on the ground in a railyard, filthy, bruised, sunburned, and wet, sharing a stolen can of beans. A train rattled past. Louie looked up. “I saw … beautiful white tablecloths and crystal on the tables, and food, people laughing and enjoying themselves and eating,” he said later. “And [I was] sitting here shivering, eating a miserable can of beans.” He remembered the money in his father’s hand, the fear in his mother’s eyes as she offered him a sandwich. He stood up and headed home.

When Louie walked into his house, Louise threw her arms around him, inspected him for injuries, led him to the kitchen, and gave him a cookie. Anthony came home, saw Louie, and sank into a chair, his face soft with relief. After dinner, Louie went upstairs, dropped into bed, and whispered his surrender to Pete.

In the summer of 1932, Louie did almost nothing but run. On the invitation of a friend, he went to stay at a cabin on the Cahuilla Indian Reservation, in southern California’s high desert. Each morning, he rose with the sun, picked up his rifle, and jogged into the sagebrush. He ran up and down hills, over the desert, through gullies. He chased bands of horses, darting into the swirling herds and trying in vain to snatch a fistful of mane and swing aboard. He swam in a sulfur spring, watched over by Cahuilla women scrubbing clothes on the rocks, and stretched out to dry himself in the sun. On his run back to the cabin each afternoon, he shot a rabbit for supper. Each evening, he climbed atop the cabin and lay back, reading Zane Grey novels. When the sun sank and the words faded, he gazed over the landscape, moved by its beauty, watching it slip from gray to purple before darkness blended land and sky. In the morning he rose to run again. He didn’t run from something or to something, not for anyone or in spite of anyone; he ran because it was what his body wished to do. The restiveness, the self-consciousness, and the need to oppose disappeared. All he felt was peace.

He came home with a mania for running. All of the effort that he’d once put into thieving he threw into track. On Pete’s instruction, he ran his entire paper route for the Torrance Herald, to and from school, and to the beach and back. He rarely stayed on the sidewalk, veering onto neighbors’ lawns to hurdle bushes. He gave up drinking and smoking. To expand his lung capacity, he ran to the public pool at Redondo Beach, dove to the bottom, grabbed the drain plug, and just floated there, hanging on a little longer each time. Eventually, he could stay underwater for three minutes and forty-five seconds. People kept jumping in to save him.

Louie also found a role model. In the 1930s, track was hugely popular, and its elite performers were household names. Among them was a Kansas University miler named Glenn Cunningham. As a small child, Cunningham had been in a schoolhouse explosion that killed his brother and left Glenn with severe burns on his legs and torso. It was a month and a half before he could sit up, and more time still before he could stand. Unable to straighten his legs, he learned to push himself about by leaning on a chair, his legs floundering. He graduated to the tail of the family mule, and eventually, hanging off the tail of an obliging horse named Paint, he began to run, a gait that initially caused him excruciating pain. Within a few years, he was racing, setting mile records and obliterating his opponents by the length of a homestretch. By 1932, the modest, mild-tempered Cunningham, whose legs and back were covered in a twisting mesh of scars, was becoming a national sensation, soon to be acclaimed as the greatest miler in American history. Louie had his hero.

In the fall of 1932, Pete began his studies at Compton, a tuition-free junior college, where he became a star runner. Nearly every afternoon, he commuted home to coach Louie, running alongside him, subduing the jimmying elbows and teaching him strategy. Louie had a rare bio-mechanical advantage, hips that rolled as he ran; when one leg reached forward, the corresponding hip swung forward with it, giving Louie an exceptionally efficient, seven-foot stride. After watching him from the Torrance High fence, cheerleader Toots Bowersox needed only one word to describe him: “Smoooooth.” Pete thought that the sprints in which Louie had been running were too short. He’d be a miler, just like Glenn Cunningham.

In January 1933, Louie began tenth grade. As he lost his aloof, thorny manner, he was welcomed by the fashionable crowd. They invited him to weenie bakes in front of Kellow’s Hamburg Stand, where Louie would join ukulele sing-alongs and touch football games played with a knotted towel, contests that inevitably ended with a cheerleader being wedged into a trash can. Capitalizing on his sudden popularity, Louie ran for class president and won, borrowing the speech that Pete had used to win his class presidency at Compton. Best of all, girls suddenly found him dreamy. While walking alone on his sixteenth birthday, Louie was ambushed by a giggling gaggle of cheerleaders. One girl sat on Louie while the rest gave him sixteen whacks on the rear, plus one to grow on.

When the school track season began in February, Louie set out to see what training had done for him. His transformation was stunning. Competing in black silk shorts that his mother had sewn from the fabric of a skirt, he won an 880-yard race, breaking the school record, co-held by Pete, by more than two seconds. A week later, he ran a field of milers off their feet, stopping the watches in 5:03, three seconds faster than Pete’s record. At another meet, he clocked a mile in 4:58. Three weeks later, he set a state record of 4:50.6. By early April, he was down to 4:46; by late April, 4:42. “Boy! oh boy! oh boy!” read a local paper. “Can that guy fly? Yes, this means that Zamperini guy!”

Almost every week, Louie ran the mile, streaking through the season unbeaten and untested. When he ran out of high school kids to whip, he took on Pete and thirteen other college runners in a two-mile race at Compton. Though he was only sixteen and had never even trained at the distance, he won by fifty yards. Next he tried the two-mile in UCLA’s Southern California Cross Country meet. Running so effortlessly that he couldn’t feel his feet touching the ground, he took the lead and kept pulling away. At the halfway point, he was an eighth of a mile ahead, and observers began speculating on when the boy in the black shorts was going to collapse. Louie didn’t collapse. After he flew past the finish, rewriting the course record, he looked back up the long straightaway. Not one of the other runners was even in view. Louie had won by more than a quarter of a mile.

He felt as if he would faint, but it wasn’t from the exertion. It was from the realization of what he was.

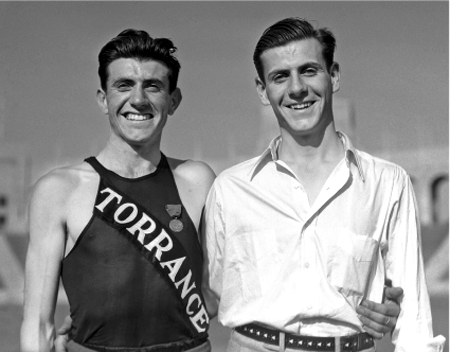

Louie wins the 1933 UCLA Cross Country two-mile race by more than a quarter of a mile. Pete is running up from behind to greet him. Courtesy of Louis Zamperini

Three The Torrance Tornado

IT HAPPENED EVERY SATURDAY. LOUIE WOULD GO TO THE track, limber up, lie on his stomach on the infield grass, visualizing his coming race, then walk to the line, await the pop of the gun, and spring away. Pete would dash back and forth in the infield, clicking his stopwatch, yelling encouragement and instructions. When Pete gave the signal, Louie would stretch out his long legs and his opponents would scatter and drop away, in the words of a reporter, “sadly disheartened and disillusioned.” Louie would glide over the line, Pete would be there to tackle him, and the kids in the bleachers would cheer and stomp. Then there would be autograph-seeking girls coming in waves, a ride home, kisses from Mother, and snapshots on the front lawn, trophy in hand. Louie won so many wristwatches, the traditional laurel of track, that he began handing them out all over town. Periodically, a new golden boy would be touted as the one who would take him down, only to be run off his feet. One victim, wrote a reporter, had been hailed as “the boy who doesn’t know how fast he can run. He found out Saturday.”

Louie’s supreme high school moment came in the 1934 Southern California Track and Field Championship. Running in what was celebrated as the best field of high school milers in history, Louie routed them all and smoked the mile in 4:21.3, shattering the national high school record, set during World War I, by more than two seconds.* His main rival so exhausted himself chasing Louie that he had to be carried from the track. As Louie trotted into Pete’s arms, he felt a tug of regret. He felt too fresh. Had he run his second lap faster, he said, he might have clocked 4:18. A reporter predicted that Louie’s record would stand for twenty years. It stood for nineteen.

Louie and Pete. Bettmann/Corbis

Once his hometown’s resident archvillain, Louie was now a superstar, and Torrance forgave him everything. When he trained, people lined the track fence, calling out, “Come on, Iron Man!” The sports pages of the Los Angeles Times and Examiner were striped with stories on the prodigy, whom the Times called the “Torrance Tempest” and practically everyone else called the “Torrance Tornado.” By one report, stories on Louie were such an important source of revenue to the Torrance Herald that the newspaper insured his legs for $50,000. Torrancers carpooled to his races and crammed the grandstands. Embarrassed by the fuss, Louie asked his parents not to watch him race. Louise came anyway, sneaking to the track to peer through the fence, but the races made her so nervous that she had to hide her eyes.

Not long ago, Louie’s aspirations had ended at whose kitchen he might burgle. Now he latched onto a wildly audacious goal: the 1936 Olympics, in Berlin. The Games had no mile race, so milers ran the 1,500 meters, about 120 yards short of a mile. It was a seasoned man’s game; most top milers of the era peaked in their mid-twenties or later. As of 1934, the Olympic 1,500-meter favorite was Glenn Cunningham, who’d set the world record in the mile, 4:06.8, just weeks after Louie set the national high school record. Cunningham had been racing since the fourth grade, and at the 1936 Games, he would be just short of twenty-seven. He wouldn’t run his fastest mile until he was twenty-eight. As of 1936, Louie would have only five years’ experience, and would be only nineteen.

But Louie was already the fastest high school miler in American history, and he was improving so rapidly that he had lopped forty-two seconds off his time in two years. His record mile, run when he was seventeen, was three and a half seconds faster than Cunningham’s fastest high school mile, run when he was twenty.* Even conservative track pundits were beginning to think that Louie might be the one to shatter precedent, and after Louie won every race in his senior season, their confidence was strengthened. Louie believed he could do it, and so did Pete. Louie wanted to run in Berlin more than he had ever wanted anything.

In December 1935, Louie graduated from high school; a few weeks later, he rang in 1936 with his thoughts full of Berlin. The Olympic trials track finals would be held in New York in July, and the Olympic committee would base its selection of competitors on a series of qualifying races. Louie had seven months to run himself onto the team. In the meantime, he also had to figure out what to do about the numerous college scholarships being offered to him. Pete had won a scholarship to the University of Southern California, where he had become one of the nation’s top ten college milers. He urged Louie to accept USC’s offer but delay entry until the fall, so he could train full-time. So Louie moved into Pete’s frat house and, with Pete coaching him, trained obsessively. All day, every day, he lived and breathed the 1,500 meters and Berlin.