Полная версия

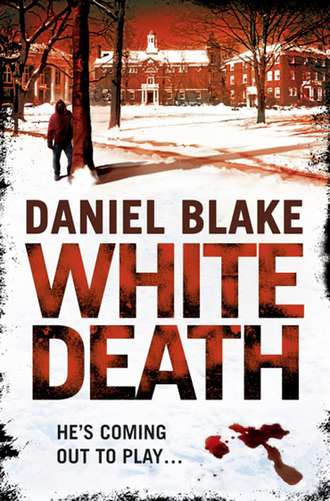

White Death

Patrese thought of the cases he’d pursued in the past. Some of them had gone on for months, and in each one he had at times felt frustrated, depressed, ready to jack it all in; but in the end he’d always kept going, and he’d always gotten a result. He was here now because he’d solved those crimes; he’d solved those crimes because he was good at what he did; and he was good at what he did because he kept plugging away and because he’d try anything to get a breakthrough.

Yes, Patrese thought: he could see how the Chariot card applied to him.

‘Next card,’ Anna said. ‘The immediate present.’

A young man standing blithely on the edge of a cliff. He carried a rose in his left hand and had a hobo’s bindle over his right shoulder. The sun shone; a small white dog played next to him.

Card zero. The Fool.

Patrese clenched the muscles in his jaw. Anna leaned forward and put her hand on his. ‘No, don’t be insulted. The Fool doesn’t mean “idiot”. In Tarot, the Fool is the spirit seeking experience. He represents the mystical intuition within each of us, the childlike ability to tune into the inner workings of the world. Each card in the major arcana can be seen as a point on the Fool’s journey through life. It’s that journey you’re on now. Where it’ll take you – well, who knows, but almost certainly not the place you think.’

Idiot or not, Patrese didn’t like being the Fool. He gestured to the next card.

‘The immediate future,’ Anna said, as she picked up.

Card XVIII. The Moon. The moon itself with a frowning face at the top of the card; great drops of dew falling from the moon to land; two tombstones; a dog and a wolf howling at the moon; a crayfish crawling from the water on to the land; and a path that disappeared into the distant unknown. Despite himself, Patrese shuddered.

‘The moon is tension, doubt, deception, confusion and fear,’ Anna said. ‘It’s sleepless nights and unsettling dreams. The dog and the wolf are our deepest fears: the crayfish hauling itself up from the deep is the base animal nature we try so hard to hide. You must make like the moon itself, Franco. Look at the frown on the face of the moon. Look at the drops of moisture. Look how hard it strives to keep those instincts down.’

Patrese wanted to get up and leave, but he couldn’t: how would it look, a Bureau agent walking out of a tarot reading? If it ever came out, he’d never live it down.

He reminded himself that it was all mumbo jumbo: cards chosen at random, images so old that no one knew any more why they’d been chosen in the first place. It might mean something to Anna, or to the wacko who’d killed Regina and Darrell, but to Patrese – determined, rational, secular Franco Patrese – it meant nothing. Nothing. Didn’t it?

Anna’s hand moved on to the fourth card, the middle one. ‘This is what’s occupying your mind right now,’ she said.

An old man standing in a wasteland. He wore a long hooded robe and a white beard. A lantern in his right hand, a staff in his left. Card IX. The Hermit.

Kwasi, Patrese thought instantly; a man always a step out of sync with the rest of us.

‘This card is introspection, solitude, the search for understanding,’ Anna said. ‘The hermit must withdraw from society to become comfortable with himself; but he must also return from isolation to share his knowledge with others. The hermit can give the insight we need to open a sealed door or conquer the forest beasts. Some say the hermit is the time we learn our true names, when we see who we really are.’

‘Fifth card,’ she said. ‘The attitudes of others.’

A young man in a red robe with a wand held high in his right hand. Above his head was the sign of infinity, a sideways figure of eight looping back endlessly on to itself. On the table in front of him was another wand, a sword, a cup and a pentacle: the four suits of the minor arcana. Flowers bloomed on the ground.

Card I: the Magician. Reversed, inverted. Anna blew through her teeth.

‘An inverted magician … that means there’s a manipulator around. He may appear helpful, but he doesn’t necessarily have your best interests at heart. He may not even be a real person: he may just be your ego, or the intoxication of power.’

Patrese looked at his watch. ‘Can we hurry this up? I have things to do.’

‘Don’t shy from this, Franco. It could be very important for you.’

‘So’s getting back to the incident room. Come on. Sixth card.’

Anna looked at him for a long moment. ‘The obstacle,’ she said eventually, reaching for the penultimate card in line. ‘Something you must overcome to resolve the situation.’

Card IV; the Emperor. An armored king on his throne, with a scepter in his right hand and a ram’s head at the end of each armrest.

‘Absolute power,’ Anna said. ‘Control, discipline, command, order, structure, tradition; also inflexibility. The Emperor symbolizes your desire to rule over your surroundings. You need to accept that some things aren’t controllable, and others may not benefit from being controlled. The emperor’s strength is stability, which brings comfort and self-worth. But his weakness is the risk of stagnation, and the sense of personal entitlement beyond your rights. You must separate one from the other.’

She looked up at Patrese. ‘Tell me. Are you impatient, or are you uncomfortable?’

He started to push his chair back. ‘I have to go.’

‘Sit.’ A sudden flash of steel in her voice. ‘Last one. The final outcome. Surely you want to know how this is going to end?’

He stayed seated. He had a feeling she’d known he would.

‘Last card.’ She rested her fingers on top of it. ‘This is how the situation will end.’

Card XVI. The Tower. Lightning striking a tower and knocking an outsize crown from off its top. Fire at the windows and two men in the foreground, falling head first towards the ground.

If Patrese had thought the Moon card was disturbing, this was another level entirely. There was nothing comforting about the image, nothing whatsoever: just violence and anguish. Even Anna looked a little taken aback.

‘What’s wrong?’ Patrese said.

‘This is … this is the card I fear the most.’

‘Now you tell me.’

‘In order, it comes right after the Devil card. It’s a bad omen. When they play tarot games in Europe, they often leave this one out. The deck we’ve got here, the original one from the fifteenth century, that doesn’t have it either. The Tower is bad, Franco. Bad. Chaos. Impact. Downfall. Failure. Ruin. Catastrophe. You want to know how bad it is? It’s the only card that’s better inverted. That way, you land on your feet.’

Anna took Patrese’s hand again, and this time the fear was in her eyes rather than his.

‘Be careful out there, Franco.’

14

Wednesday, November 3rd

Cambridge, MA

Building 32 of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, better known as the Stata Center, is a whimsical cartoon village, a riot of angles and perspective. Walls swerve and collide, columns lean like Pisan towers, surfaces change color and texture at the drop of a hat, from dark brick to brushed aluminum, saffron paint to mirrored steel. Crumpled and concertinaed, the building looked as though it had suffered an earthquake.

In an office with walls that sloped so violently no bookshelves would stand flush against them, Marat Nursultan sipped at his coffee.

‘You’re sure you haven’t heard from him?’ he said.

Thomas Unzicker shook his head. He wore square-rimmed glasses and a WHO THE FUCK ARE HARVARD? sweatshirt. He was twenty-four, and still got ID-checked in pretty much every bar from here to Cape Cod.

Nursultan clattered his spoon into the saucer. ‘We have to get hold of him.’

Unzicker stared at Nursultan a good ten seconds before replying. Nursultan didn’t break the gaze. Unzicker rarely spoke unless the subject was computers, when you couldn’t shut him up; but otherwise, almost nothing. Nursultan didn’t know whether Unzicker was just shy or whether it was something deeper, more pathological. He didn’t care, either way. He wanted Unzicker for his peculiar form of genius, not for his company.

‘His mom’s dead.’ Unzicker’s voice was little more than a whisper. Nursultan had to lean forward to hear it. It was always like this. If a door slammed or someone was talking outside, you had to ask Unzicker to repeat himself; that’s how quietly he spoke.

‘I want to talk with him. Much important on this, you know. He being difficult before his mother dead. He try to play me both way, yes? Be difficult with title match, get advantage on this project. Or maybe other way round. But I not have it. I not do business that way. So tell me: you need him for this?’

‘Yes.’

‘Really need him?’

‘Yes.’

‘You can’t do it on your own? Or get someone else in for him?’

‘No.’

‘Why not?’

‘This thing’s only going to work with the kind of chess Kwasi plays.’

‘There are other super-grandmasters.’

Unzicker shook his head again. ‘Too much to explain to someone new.’

‘If someone beats us to it …’ Unzicker shrugged; Nursultan kept talking. ‘You sure no one else know about this?’ Headshake. ‘What that mean? Yes, no one know, or no, you not sure?’

‘I haven’t told anyone.’

‘The police? They been round?’ Headshake. ‘They check up on things. They want to find out about his mother, they examine every bit of his life, then they find us.’

‘We’re not doing anything illegal.’

‘No. But what we do, it is secret.’ He rubbed his fingers together. ‘Valuable.’

Unzicker said nothing. In the corridor outside, a quartet of students in gym shorts padded past. A squeal of laughter from the day-care center echoed off the walls.

Nursultan looked out of the window, across a roofscape dotted with Technicolor huts. MIT, he thought, was supposed to be about reason, logic, engineering excellence. But this building was like one of those car-crash sculptures, like someone had just thrown it up. It didn’t even look finished. And that was the point. What Unzicker was doing here, what everyone was doing here, it was all nothing more than work in progress. Science was an open question. Every discovery made was merely a stepping stone to the next one.

Frank Gehry, who’d designed this place, had said the same about his buildings: they always looked more interesting under construction than when they were finished. That’s what he’d wanted here: that restless sense of something still happening. The floorplans looked like fractals. That was deliberate, to make sure the people inside didn’t think linearly. They were doing research that could change the world, they had to think in weird dimensions. If the building looked like it was leaping off the planet, so were the people inside. That was the theory, anyway.

Nursultan smiled and stood. ‘Moment you hear something, you tell me. Remember who pay you. Remember how much more I pay when we make this work.’

He patted Unzicker on the shoulder. It felt to Unzicker like the grasp of a bear’s claw.

15

Thursday, November 4th

Patrese had settled in to New Haven for the long haul, whether he liked it or not. The Bureau had booked him a room – special rates for government employees, naturally – in the downtown New Haven Hotel, conservatively named and conservatively decorated in various tones of corporate taupe.

He’d had the New Orleans field office FedEx him up a bunch of his suits, dress shirts and black leather Oxfords so he’d actually look like a Bureau agent. All he’d had packed when Kieseritsky had first called on Sunday morning was casual clothes for a weekend at the football.

He’d spent the past couple of days following up leads that had started without promise and had become even more hopeless. In the process, he’d gotten himself acquainted with the city’s geography and neighborhoods. Westville, East Rock and the East Shore were the ‘best’ – for which, read ‘richest’ – places to live. Fair Haven, the Hill and Dwight-Kensington were at the other end of the scale. As was so often the case, Patrese thought, the prettier the name, the bigger the shithole.

The first forty-eight hours after the murders had come and gone, and with them the hope that this thing might get solved quick and clean. The task force had followed up any known cases of criminal pairings, be they siblings, couples, friends, colleagues or any other imaginable permutation. Nothing doing.

And meantime, pressure was mounting from several directions at once. The press were clamoring for more information, which meant an arrest or another victim. Kwasi King wanted his mother’s body back so he could give her a proper burial, but the medical examiner wanted to keep hold of it a while longer, perhaps even till the crime was solved. Patrese had rung Kwasi to tell him. Kwasi had delivered himself of an unflattering opinion of medical examiners in general and the New Haven one in particular. Kwasi was well into the anger phase of grief, Patrese had thought.

Anna’s tarot reading had freaked Patrese more than he wanted to admit. The Fool had annoyed him; the Moon had unsettled him; and as for the Tower, men diving to earth while the building burned behind them … it reminded him of the pictures from New York on the day seared into America’s collective memory, when some of those trapped above the firelines in the Twin Towers had been pushed or jumped to their lonely, brutal deaths. An uncanny harbinger of that tragedy, no? If the Tarot was right about that, what else might it be right about?

Now Patrese was in the hotel bar, about to order dinner before turning in for the night. He couldn’t be bothered to go out, but equally he thought it defeatist to order room service. Hence the bar.

The waitress informed him that tonight’s special was apizza, a white clam pie pizza with a thin crust and no mozzarella. Apizza was New Haven’s main contribution to world cuisine, and boy did you know it when you were here. If one more person in this town asked Patrese whether he’d tried it, he might start committing murders himself rather than trying to solve them.

His cellphone rang. He held a finger up to the waitress: let me get this.

The display showed a 212 number. Manhattan code. Kwasi?

‘Patrese.’

‘Agent Patrese?’ A man’s voice, deep and rough: not Kwasi’s. ‘My name is Bobby Dufresne. I’m a detective with the NYPD, Twenty-Sixth Precinct.’

He didn’t need to tell Patrese why he was calling.

16

It’s seventy-five miles, give or take, between downtown New Haven and the campus of Columbia University in Upper Manhattan’s Morningside Heights district. Lights flashing and sirens blaring, Patrese managed the journey inside forty-five minutes.

He found his way to the murder site easily enough: it was lit up by the blues and reds lazily rotating on the roofs of the half-dozen police cruisers in attendance. At the main entrance to an austere-looking stone building, two uniforms stood guard behind crime-scene tape. A hundred or so students milled around, weeping on each other’s shoulders or talking dazedly into cellphones. A shrine seemed to be growing organically on a patch of grass nearby: candles, photographs, T-shirts, scarves.

HARTLEY, proclaimed letters on the building’s front wall. Patrese turned sideways, edged through a gap between two students, and flipped his badge at the uniforms. One of them stepped forward and lifted up the tape for him to duck under.

‘Down the corridor, sir. It’s right at the end, in the corner.’

‘Thanks.’

Crime-scene officers flitted through bright pools of arc lights. Halfway along the corridor, Patrese stopped one of them and asked where he could find Detective Dufresne.

‘Right over there.’ A finger swathed tight in blooded latex pointed at a black man by the far wall. Dufresne had a sports jacket and a goatee beard trimmed to what looked like an accuracy of micrometers. He came across, hand extended.

‘Agent Patrese?’ A glance at his watch. ‘Where’s Mario?’

Patrese stiffened. An Italian insult right off the bat?

‘Mario?’ He kept his voice neutral.

‘Andretti. No other way you could have got here this fast.’

Patrese laughed. ‘Mario’s got the night off. Dale said he’d drive instead.’

Dufresne clapped him on the shoulder. ‘Glad you made it. Pleasure to meet you. Heard a lot about you, all that stuff down in New Orleans round about Katrina. Took an interest in the voodoo side, for obvious reasons.’

Patrese made a quick calculation: black skin, French name, voodoo, New York’s diaspora. ‘You’re Haitian?’

‘Came here when I was nine. Never going back. Anyhows, I can give you my life story sometime else.’ He gestured toward the corner room. ‘You wanna go on in?’

‘Sure.’ Patrese started to walk toward the room. ‘What happened?’

‘Deceased’s name is Dennis Barbero. President of Columbia’s BSO, the Black Students Organization. Not as minority as you might think, this being Ivy League and all. Columbia’s got more black students than most, and the, er, head guy, the president of the university, he’s a big fan of affirmative action.’

‘You got an ID so fast?’

‘Excuse me? Oh, you mean ’cos he’s got no head and shit? Yeah, yeah, definitely him. Definitely Dennis Barbero. Public Enemy T-shirt he always wore, that’s on the, er, body, and also, he’s one of the few who had a key to open this room up.’

They reached the door. Dufresne gestured: After you.

‘G-body meeting of the BSO, every …’

‘G-body?’

‘General body. General meeting. Every Thursday, nine till eleven, right in here, but it’s locked when not in use. Dennis had to open it up.’

There was a sign on the door. MALCOLM X LOUNGE, 106 HARTLEY HALL.

Patrese stepped inside.

Blood everywhere, all over the walls and floor, as though a herd of pigs had been slaughtered in here rather than one man. Dennis’ body was sprawled between a table and two chairs. Unlike Regina King and Darrell Showalter, he was clothed. Like them, he was missing a head and one of his arms.

The Public Enemy T-shirt had the band’s famous logo: the silhouette of a black man’s head with a beret, as seen through rifle sights. The shirt had ridden up to reveal the missing patch of skin. The left arm of his shirt had been severed, along with the arm itself. There was a tarot card near the body, but it was too far away for Patrese to make out exactly what it was.

He looked round the room. On the near wall, a painting – Sherman Edwards’ My Child, My Child, according to a card alongside – from which a staggeringly beautiful black woman, dressed in a purple shawl and clutching a naked baby tight to her chest, stared at Patrese in silent, reproachful challenge. Directly opposite was a poster-sized photo of Malcolm X himself, lips pursed, right index finger raised, old-fashioned radio microphone in front of him, and beneath it a quotation:

‘We declare our right on this Earth to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being.’

And to be killed like an animal, Patrese thought bitterly.

He went closer, careful not to step in any of the outlying islands of blood. He peered at the tarot card. A young man in armor astride a charging horse, sword held high in his right hand. The Knight of Swords.

Since Anna had told his fortune, Patrese had pondered and studied the major arcana with a fervor some might have thought obsessional. He knew this card wasn’t among them. The knight of swords was minor arcana, the lesser secrets. He’d have to go back to Anna tomorrow and pick her brains all over again.

No tarot reading, though; not after last time. That was for damn sure.

He turned to Dufresne. ‘Give me the timescale. What do we know?’

‘I’ll walk you through it; it’s easier. Let’s get out of here.’

17

The Columbia campus stretches over six city blocks, but in the last few hours of his life, Dennis had moved within only one of them. Hartley Hall was located at the eastern side of this block, on 114th and Amsterdam: Dufresne took Patrese over to Alfred Lerner Hall on the western side, 114th and Broadway. Patrese glanced at the 114th Street sign.

‘Across 110th Street, huh?’ he said.

Dufresne laughed. ‘Oh, you’re not in Harlem yet. 110th Street’s the marker only over to the Upper East. Round this side of the park, us niggers don’t start in earnest till north of 125th. Matter of fact, this precinct’s one of the safest in the city. Till tonight.’

There was another uniform at the entrance to Lerner Hall. He snapped to attention as Dufresne approached.

‘Easy, son,’ Dufresne said. ‘This ain’t Crimson Tide.’

Dufresne and Patrese rode the elevator to the sixth floor, where Dufresne led the way through two sets of fire doors to a sign: WKCR, 89.9 FM. Columbia University Student Radio Station.

‘Dennis was here, seven thirty till eight thirty. Did it every week: Dennis Barbero’s Black Music Hour. Played whatever he wanted to play, long as it was black. Could be Martha Reeves or Kool Herc, could be Gladys Knight or Grandmaster Flash. One of the most popular shows they have.’ He made a face. ‘Had.’

Patrese smiled: it was the most natural mistake in the world.

‘Anyhows,’ Dufresne continued, ‘show finishes eight thirty. Dennis hands over to the guy doing the news headlines – on the half-hour, short ones only – says adios to the producer, and leaves.’ He took Patrese back through the fire doors, down again in the elevator, and through the main foyer. ‘A couple of people see him here, leaving the building.’

‘What time is this?’

‘About eight thirty-five.’

They left the hall and headed across the quadrangle.

To their right, on the south side, was an enormous neo-classical library fronted by an arcade of Ionic columns. Above the columns ran a frieze of famous writers’ names, starting with Homer and Herodotus and ending with Voltaire and Goethe. To their left, a sculpture of the goddess Athena sitting on a throne, with a laurel crown on her head and the book of knowledge balanced on her lap. Her arms were raised as though welcoming the knowledge all around her.

Whatever accusations you could level at Ivy League colleges, Patrese thought, understatement wasn’t one of them.

‘From Lerner to Hartley, probably seven minutes, walking at normal pace,’ Dufresne said. ‘Well-lit, people around, usually a couple of campus police patrols too.’

‘You think he was followed?’

‘Maybe. Wouldn’t have dared jump him out here, though. No chance of getting away unseen. But maybe he wasn’t followed. Every Thursday, Dennis had the same routine: his radio show, walk across the quad, open up the Malcolm X Lounge, make sure everything was ready for the G-body meeting at nine. Didn’t need to follow him. You could set your watch by him. Hell, you could set the atomic clock by him.’

‘So Dennis unlocks the lounge, the killer slips in there with him—’

‘Or has gotten access to the room beforehand, and is lying in wait.’

‘—or that, and then he kills Dennis and hauls ass. Must have had a holdall or something, to carry the head and arm in. Anyone see anyone like that?’

‘Not that we know.’

Patrese shrugged. If the killer was smart – and they knew he was that, if nothing else – he’d have made sure that he attracted as little attention as possible. On a student campus, that meant dressing like a student, whether you were one or not. Sneakers, jeans, college sweatshirt; someone dressed in those would pass unnoticed, even with a holdall. Going to the gym, helping set up a party … plenty of reasons to carry a soft bag.