Полная версия

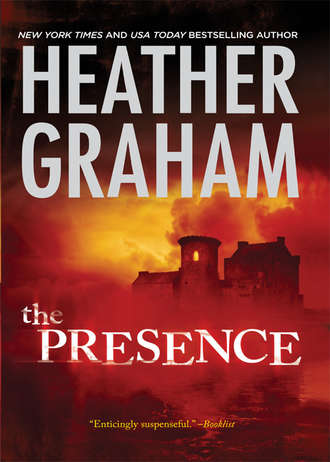

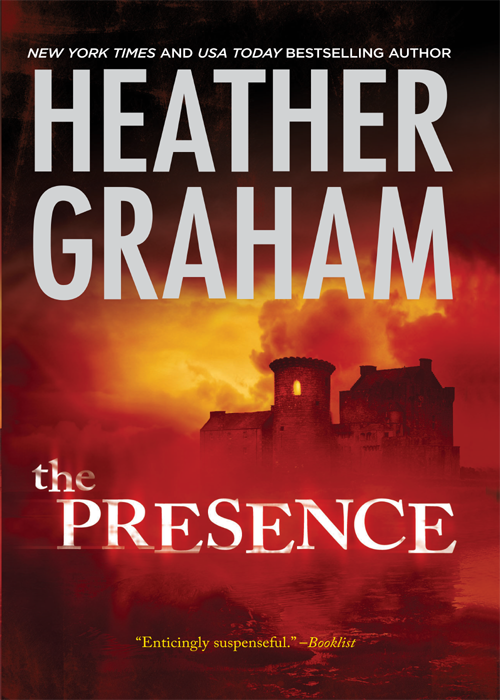

The Presence

Praise for the novels of Heather Graham

“An incredible storyteller.”

—Los Angeles Daily News

“Graham does a great job of blending

just a bit of paranormal with real, human evil.”

—Miami Herald on Unhallowed Ground

“A fast-paced and suspenseful read

that will give readers chills while

keeping them guessing until the end.”

—RT Book Reviews on Ghost Moon

“There are good reasons for Graham’s

steady standing as a bestselling author.

Graham’s atmospheric depiction of a lost city

is especially poignant.”

—Booklist on Ghost Walk

“Graham’s latest is nerve-racking in the extreme,

solidly plotted and peppered with

welcome hints of black humor. And the ending’s

all readers could hope for.”

—RT Book Reviews on The Last Noel

“[A] spooky post-Katrina mystery … Dream

messages and premonitions, ghostly sightings,

capable detective work and fascinating characters

blend to make a satisfying chiller.”

—Publishers Weekly on Deadly Night

“Mystery, sex, paranormal events.

What’s not to love?”

—Kirkus Reviews on The Death Dealer

Also by HEATHER GRAHAM

NIGHT OF THE VAMPIRES

GHOST MOON

GHOST NIGHT

GHOST SHADOW

THE KILLING EDGE

NIGHT OF THE WOLVES

HOME IN TIME FOR CHRISTMAS

UNHALLOWED GROUND

DUST TO DUST

NIGHTWALKER

DEADLY GIFT

DEADLY HARVEST

DEADLY NIGHT

THE DEATH DEALER

THE LAST NOEL

THE SÉANCE

BLOOD RED

THE DEAD ROOM

KISS OF DARKNESS

THE VISION

THE ISLAND

GHOST WALK

KILLING KELLY

THE PRESENCE

DEAD ON THE DANCE FLOOR

PICTURE ME DEAD

HAUNTED

HURRICANE BAY

A SEASON OF MIRACLES

NIGHT OF THE BLACKBIRD

NEVER SLEEP WITH STRANGERS

EYES OF FIRE

SLOW BURN

NIGHT HEAT

the

PRESENCE

HEATHER

GRAHAM

www.mira.co.uk

For Rich Devin, Lance Taubald, Leslie and

Leland Burbank, Connie Perry, Jo Carol,

Peggy McMillan, Sharon Spiak,

Sue-Ellen Wellfonder, Kathryn Falk and Rubin,

with much love—and to great memories of

streams and castles in Scotland.

Prologue

Nightmares

The scream rose and echoed in the night with a bloodcurdling resonance that only the truly young, and truly terrified, could create.

Her parents ran into the room, called by instinct to battle whatever force had brought about such absolute horror in their beloved child.

Yet there was nothing. Nothing but their nine-year-old, standing on the bed, arms locked at her side, fingers curled into her fists with a terrible rigidity, as if she had suddenly become an old woman. She was screaming, the sound coming again and again, high, screeching, tearing, like the sound of fingernails dragged down the length of a blackboard.

Both parents looked desperately around the room, then their eyes met.

“Sweetheart, sweetheart!”

Her mother came for her unnoticed and tried to take the girl into her arms, but she was inflexible. The father came forward, calling her name, taking her and then shaking her. Once again, she gave no notice.

Then she went down. She simply crumpled into a heap in the center of the bed. Again the parents looked at one another, then the mother rushed forward, sweeping the girl into her arms, cradling her to her breast. “Sweetie, please, please …! ”

Blue eyes, the color of a soft summer sky, opened to hers. They were filled with angelic innocence. The child’s head was haloed by her wealth of white-blond hair, and she smiled sleepily at the sight of her mother’s face, as if nothing had happened, as if the bone-jarring sounds had never come from her lips.

“Did you have a nightmare?” her mother asked anxiously.

Then a troubled frown knit her brow. “No!” she whispered, and the sky-blue eyes darkened, the fragile little body began to shake.

The mother looked at her husband, shaking her head. “We’ve got to call the doctor.”

“It’s two in the morning. She’s had a nightmare.”

“We need to call someone.”

“No,” her father said firmly. “We need to tuck her back into bed and discuss it in the morning.”

“But—”

“If we call the doctor, we’ll be referred to the emergency room. And if we go to the emergency room, we’ll sit there for hours, and they’ll tell us to take her to a shrink in the morning.”

“Donald!”

“It’s true, Ellen, and you know it.” Ellen looked down. Her daughter was staring at her with huge eyes, shaking now. “The police!” she whispered. “The police?” Ellen asked.

“I saw him, Mommy. I saw what that awful man did to the lady.”

“What lady, darling?”

“She was on the street, stopping cars. She had big red hair and a short silver skirt. The man stopped for her in a red car with no top, like Uncle Ted’s. She got in with him and he drove and then … and then …”

Donald walked across the room and took hold of his daughter’s shoulders. “Stop this! You’re lying. You haven’t been out of this room!”

Ellen shoved her husband away. “Stop it! She’s terrified as it is.”

“And she wants us to call the police? Our only child will wind up on the front page of the papers, and if they don’t catch this psycho murdering women, he’ll come after her! No, Ellen.”

“Maybe they can catch him,” Ellen suggested softly.

“You have to forget it!” Donald said sternly to his daughter.

She nodded gravely, then shook her head. “I have to tell it!” she whispered.

Ellen seldom argued with Donald. But tonight she had picked her battle.

“When this happens … you have to let her talk.”

“No police!” Donald insisted.

“I’ll call Adam.”

“That shyster!”

“He’s no shyster and you know it.”

Donald’s eyes slid from his wife’s to those of his daughter, which were awash in misery and a fear she shouldn’t have to know. “Call the man,” he said.

* * *

He was very old; that was Toni’s first opinion of Adam Harrison. His face was long, his body was thin, and his hair was snow-white. But his eyes were the kindest, most knowing, she had seen in her nine years on earth.

He came to the bedside, took her hand, clasped it firmly between his own and smiled slowly. She had been shaking, but his gentle hold eased the trembling from her, just as it warmed her. He was very special. He understood that she had seen what she had seen without ever leaving the house. And she knew, of course, that it was ridiculous. Such things didn’t happen. But it had happened.

She hated it. Loathed it. And she understood her father’s concern. It was a very bad thing. People would make fun of her—or they would want to use her ability for their own purposes.

“So, tell me about it,” Adam said to her, after he had explained that he was an old friend of her mother’s family.

“I saw it,” she whispered, and the shaking began again.

“Tell me what you saw.”

“There was a woman on the street, trying to get cars to stop. One stopped. She leaned into it, and she started to talk to the man about money. Then she went with him. She got into the car. It was red.”

“It was a convertible?”

“Like Uncle Ted’s car.”

“Right,” he said, squeezing her hand again.

Her voice became a monotone. She repeated some of the conversation between the man and woman word for word. Perspiration broke out on her body as she felt the woman’s growing sense of fear. She couldn’t breathe as she described the knife. She was drenched with sweat at the end, and cold. So cold. He talked to her and assured her.

Then the police arrived, called by neighbors who were awakened by her screams.

The two officers flanked her bed and started firing questions at her, demanding to know what she had seen—or what had been done to her.

Despite the terror, she felt all right because of Adam. But then huge tears formed in her eyes. “Nothing, nothing! I saw nothing!”

Adam rose, his voice firm and filled with such authority that even the men with their guns and badges listened to him. They left the room. Adam winked at her and went with the men, telling her that he would talk to them.

A month later, the police came back to the house. She could hear her father angrily telling them that they had to leave her alone. But despite his argument, she found herself facing a police officer who kept asking her terrible questions. He described horrific things, his voice growing rougher and rougher. Somewhere in there, she closed off. She couldn’t bear to hear him anymore.

She woke up in the hospital. Her mother was by her side, tears in her eyes. She was radiant with happiness when Toni blinked and looked at her.

Her father was there, too. He kissed Toni on the forehead, then, choking, left the room. An older man in the back stepped up to her.

“You’re going to move,” he told her cheerfully. “Out to the country. The police will never come again.” “The police?”

“Yes, don’t you remember?”

She shook her head. “I’m sorry … I’m really sorry. I don’t know who you are.”

He arched a fuzzy white brow, staring at her. “I’m Adam. Adam Harrison. You really don’t remember me?”

She studied him gravely and shook her head. She was lying, but he just smiled, and his smile was warm and comforting.

“Just remember my name. And if you ever need me, call me. If you dream again, or have a nightmare.”

“I don’t have nightmares,” she told him.

“If you dream …”

“Oh, I’m certain I don’t have dreams. I don’t let myself have dreams. Some people can do that, you know.”

His smile deepened. “Yes, actually, I do know. Well, Miss Antoinette Fraser, it has been an incredible pleasure to see you, and to see you looking so well. If you ever just want to say hello, remember my name.”

She gripped his hand suddenly. “I will always remember your name,” she told him.

“If you ever need me, I’ll be there,” he promised.

He brushed a kiss on her forehead, and then he was gone. Just a whisper of his aftershave remained.

Soon her memory faded and the whole thing became vague, not real. There was just a remnant in her mind, no more than that whisper of aftershave when someone was really, truly gone.

Interlude When Cromwell Reigned

From his vantage point, MacNiall could see them, arrayed in all their glittering splendor. The man for whom they fought, the ever self-righteous Cromwell, might preach the simplicity and purity one should seek in life, but when he had his troops arrayed, he saw to it that no matter what their uniform, they appeared in rank, and their weapons shone, as did their shields.

As it always seemed to be with his enemy, they were unaware of how a fight in the Highlands might best be fought. They were coming in their formations. Rank and file. Stop, load, aim, fire. March forward. Stop, load, aim, fire….

Cromwell’s troops depended on their superior numbers. And like all leaders before him, Cromwell was ready to sacrifice his fighting man. All in the name of God and the Godliness of their land—or so the great man preached.

MacNiall had his own God, as did the men with whom he fought. For some, it was simply the God that the English did not face. For others, it had to do with pride, for their God ruled the Scottish and Presbyterian church, and had naught to do with an Englishman who would sever the head of his own king.

Others fought because it was their land. Chieftains and clansmen, men who would not be ruled by such a foreigner, men who seldom bowed down to any authority other than their own. Their land was hard and rugged. When the Romans had come, they had built walls to protect their own and to keep out the savages they barely recognized as human. In the many centuries since, the basic heart of the land had changed little. Now, they had another cause—the return of the young Stuart heir and their hatred for their enemy.

And just as they had centuries before, they would fight, using their land as one of their greatest weapons.

MacNiall granted Cromwell one thing—he was a military man. And he was no fool. He had called upon the Irish and the Welsh, who had learned so very well the art of archery. He had called upon men who knew about cannons and the devastating results of gunpowder, shot and ball, when put to the proper use. All these things he knew, and he felt a great superiority in his numbers, in his weapons.

But still, he did not know the Highlands, nor the soul of the Highland men he faced. And today he should have known the tactics the Highlander would use more so than ever. For MacNiall had heard that these troops were being led by a man who had been one of their own, a Scotsman from the base of the savage lands himself.

Grayson Davis—turncoat, one who had railed against Cromwell. Yet one who had been offered great rewards—the lands of those he could best and destroy.

Like Cromwell, Davis was convinced that he had the power, the numbers and the right. So MacNiall counted on the fact that he would underestimate his enemy—the savages from the north, ill equipped, unkempt, many today in woolen rags, painted as their ancestors, the Picts, fighting for their land and their freedom.

Rank and file, marching. Slow and steady, coming ever forward. They reached the stream.

“Now?” whispered MacLeod at his side.

“A minute more,” replied MacNiall calmly.

When the enemy was upon the bridge, MacNiall raised a hand. MacLeod passed on the signal.

Their marksman nodded, as quiet, calm and grim as his leaders, and took aim.

His shot was true.

The bridge burst apart in a mighty explosion, sending fire and sparks skyrocketing, pieces of plank and board and man spiraling toward the sky, only to land again in the midst of confusion and terror, bloodshed and death. For they had waited. They had learned patience, and the bridge had been filled.

Lord God, MacNiall thought, almost wearily. By now their enemies should have learned that the death and destruction of human beings, flesh and blood, was terrible.

“Now?” said MacLeod again, shouting this time to be heard over the roar from below.

“Now,” MacNiall said calmly.

Another signal was given, and a hail of arrows arched over hill and dale, falling with a fury upon the mass of regrouping humanity below.

“And now!” roared MacNiall, standing in his stirrups, commanding his men.

The men, flanking those few in view, rose from behind the rocks of their blessed Highlands. They let out their fierce battle cries—learned, perhaps, from the berserker Norsemen who had once come upon them—and moved down from rock and cliff, terrible in their insanity, men who had far too often fought with nothing but their bare hands and wits to keep what was theirs, to earn the freedom that was a way of life.

Clansmen. They were born with an ethic; they fought for one another as they fought for themselves. They were a breed apart.

MacNiall was a part of that breed. As such, he must always ride with his men, and face the blades of his enemy first. He must, like his fellows, cry out his rage at this intrusion, and risk life, blood and limb in the hand-to-hand fight.

Riding down the hillside, he charged the enemy from the seat of his mount, hacking at those who slashed into the backs of his foot soldiers, and fending off those who would come upon him en masse. He fought, all but blindly at times, years of bloodshed having given him instincts that warned him when a blade or an ax was at his back. And when he was pulled from his mount, he fought on foot until he regained his saddle and crushed forward again.

In the end, it was a rout. Many of Cromwell’s great troops simply ran to the Lowlands, where the people were as varied in their beliefs as they were in their backgrounds. Others did not lay down their arms quickly enough, and were swept beneath the storm of cries and rage of MacNiall’s Highlanders. The stream ran red. Dead men littered the beauty of the landscape.

When it was over, MacNiall received the hails of his men, and rode to the base of the hill where they had collected the remnants of the remaining army. There he was surprised to see that among the captured, his men had taken Grayson Davis—the man who had betrayed them,

one of Cromwell’s greatest leaders, sworn to break the back of the wild Highland resistance. Grayson Davis, who hailed from the village that bordered MacNiall’s own, had seen the fall of the monarchy and traded in his loyalty and ethics for the riches that might be acquired from the deaths of other men.

The man was wounded. Blood had all but completely darkened the glitter of the chest armor he wore. His face was streaked with grimy sweat.

“MacNiall! Call off your dogs!” Davis roared to him.

“He loses his head!” roared Angus, the head of the Moray clan fighting there that day.

“Aye, well, and he should be executed as a traitor, as the lot of us would be,” MacNiall said without rancor. They all knew their punishment if they were taken alive. “Still, for now he will be our captive, and we will try him in a court of his peers.”

“What court of jesters would that be? You should bargain with Lord Cromwell, use my life and perhaps save our own, for one day you will be slain or caught!” Davis told him furiously. And yet, no matter his brave words, there was fear in his eyes. There must be, for he stood in the midst of such hatred that the most courageous of men would falter.

“If you’re found guilty, we’ll but take your head, Davis,” MacNiall said. “We find no pleasure in the torture your kind would inflict upon us.”

Davis let out a sound of disgust. It was true, on both sides, the things done by man to his fellow man were surely horrendous in the eyes of God—any god.

“There will be a trial. All men must answer to their choices,” MacNiall said, and his words were actually sorrowful. “Take him,” he told Angus quietly.

Davis wrenched free from the hold of his captors and turned on MacNiall. “The great Laird MacNiall, creating havoc and travesty in the name of a misbegotten king! All hail the man on the battlefield! Yet what man rules in the great MacNiall’s bedchamber? Did you think that you could leave your home to take to the hills, and that the woman you left behind would not consider the fact that one day you will fall? Aye, MacNiall, all men must deal with their choices! And yours has made you a cuckold!”

A sickness gripped him, hard, in the pit of his stomach. A blow, like none that could be delivered by a sword or bullet or battle-ax. He started to move his horse forward.

Grayson Davis began to laugh. “Ah, there, the great man! The terror of the Highlands. The Bloody MacNiall! She wasn’t a victim of rape, MacNiall. Just of my sword. A different sword.”

Grayson Davis’s laughter became silent as Angus brought the end of a poleax swinging hard against his head. The man fell flat, not dead—for he would stand trial—but certainly when he woke his head would be splitting.

Angus looked up at MacNiall.

“He’s a liar,” Angus said. “A bloody liar! Yer wife loves ye, man. No lass is more honored among us. None more lovely. Or loyal.”

MacNiall nodded, giving away none of the emotion that tore through him so savagely. For there were but two passions in his life—his love for king and country … and for his wife. Lithe, golden, beautiful, sensual, brave,

eyes like the sea, the sky, ever direct upon his own, filled with laughter, excitement, gravity and love. Annalise.

Annalise … who had begged him to set down his arms. To rectify his war with Cromwell. Who had warned him that … there could be but a very tragic ending to it all.

1

“Imagine, if you will, the great laird of the castle! The MacNiall himself, famed and infamous, a figure to draw both fear and awe. Ahead of his time, he stood nearly six foot three, hair as black as pitch, eyes the silver gray of steel, capable of glinting like the devil’s own. Some say those orbs burned with the very fires of hell. His arms were knotted with muscle from the wielding of his sword, his ax, whatever weapon fell his way in the midst of battle. It was said that he could take down a dozen men in the opening moments of a fray. Passionate for king and country, he would fight any man who spoke to wrong either. Passionate in love, his anger could rage just as deeply against a woman, if he felt himself betrayed.

“Imagine, then, being his beloved, his bride, his wife, burdened with the most treacherous of advisors, men determined to find a way to bring down a man so great in battle, to further their own aims. Imagine her knowing that she had been betrayed, maligned, and that her laird husband was returning from the blood of the battlefield … intent upon a greater revenge. There … there! He would come to the great doors that gave entry to the hall.”

Toni stood at the railing of the second-floor balcony, pointing to the massive double doors, high on sheer exhilaration. A crowd of awed tourists were gathered below her in the great hall entry, staring up at her.

This was really too good, far more than they had imagined they could accomplish when she and the others had set their wild dream about procuring a run-down castle and creating a very special entertainment complex out of it. So far, David and Kevin had rallied their crowd magnificently by playing a pair of hapless minstrels in the reign of James IV, when the current structure had been built upon the Norman bastion begun by thirteenth-century kings. Ryan and Gina had done a fantastic job playing the daughter of the laird and the stable boy with whom she had fallen tragically in love during the reign of Mary, Queen of Scots. Thayer—the wild card in their sextet—had proved himself more than capable of portraying a laird accused of witchcraft in the time of James VI. And they had all run around as kitchen wenches or servants for one another.

Beyond a doubt, the crowd was into the show. Below, they waited. So Toni continued.

“Alas, it was right here, as I stand now, where, tragically, Annalise met with her husband, that great man of inestimable prowess and, unfortunately, jealousy and rage. Believing the stories regarding his beautiful wife, he curled his fingers around her throat, squeezing the life from her before tossing her callously down the staircase in a fit of uncontrollable wrath. Since he was the great laird of the castle, his servants helped him dispose of the body, and Laird MacNiall went on to fight another day. He was, however, to receive his own just rewards. Though he had bested many, and countless troops had been slaughtered beneath his leadership, Cromwell was to seize the man at last. He received the ultimate punishment: being castrated, disemboweled, decapitated, dismembered and dispersed. His pieces were then gathered by his descendants, and he now lies buried deep within the crypt of these very stone walls! Ah, yes, his mortal remains are buried here. But it’s said that his soul wanders, not just around the castle itself, but through the surrounding hills and braes, and he is known to haunt the forest just beyond the ruins of the old town wall.”