Полная версия

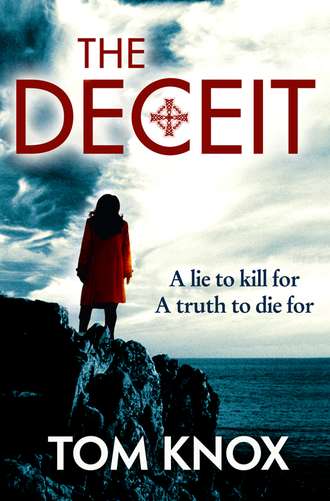

The Deceit

The moment was tense. Ryan drank his tea, and said nothing, and watched the moon rise over the Temple of Seti. He remembered Rhiannon. Her fever, the last days, the terrifying and inundating sadness. Maybe it was time to let this go.

The moon stared at him. Shocked at his decision. But the decision felt entirely right.

He took leave of absence that very night, hastily packing a bag, then jogging straight to the teeming Abydos railway station.

Time was strictly limited. Ryan was very aware that others would be on the trail. He had to get to Nazlet as quickly as possible. But quickly as possible was not an Egyptian state of mind.

The ticket queue was full of sweating men in djellabas, all shouting angrily at the narrow-eyed man behind the cracked-glass reservations window. The man behind the glass was dispensing his tickets with a reluctant and painful slowness, as if they were his personal inheritance of Treasury bonds. Harper growled with impatience. They’d found the body of Victor Sassoon!

Sassoon was his old tutor, his mentor, a man Harper had once admired and revered: the great Jewish scholar of the Dead Sea Scrolls, one of the greatest men in his field. What had happened that he should be found dead, alone, in a cave? What could have driven him to do that? To walk into the wilderness, alone, two months ago? Poor Victor.

It had to have been something extraordinary to invoke such a response. That meant the bag found with Sassoon’s body must contain the Sokar Hoard, the great cache: the cache Victor had illegally bought in his final days of life, or so the lurid rumours had it. Sassoon had, it seemed, read these documents, then killed himself. Or been murdered. Why? What had Sassoon retrieved at the White Monastery? What was in those texts?

The mysteries were arousing, energizing, tantalizing. They pumped the blood in Harper’s heart. Hassan was right. All these years the keen and ambitious scientist in Ryan Harper hadn’t entirely gone away, but had merely slumbered. And now the long-buried Egyptologist was being resurrected.

If Ryan could find the Sokar Hoard, then he would have done something with the scholarly skills he had disregarded for a decade. Something amazing.

Did you hear about old Ryan Harper? Oh, he found the Sokar Hoard.

Ryan Harper?

‘Effendi!’

‘Maljadeed!’

The queue in front of him seemed to be getting longer as half of Abydos barged in. Harper resisted the urge to punch his way to the kiosk. But it was hard. Trying to buy a ticket in an Egyptian railway station was always a hassle – like trying to change nationality during a hurricane – and he knew he had to exercise patience. But he couldn’t exercise patience tonight of all nights. The next Sohag train – the last Sohag train of the day – was leaving in fifteen minutes.

‘La – ibqa!’

‘Jagal – almaderah – incheb!’

What could he do instead? He crunched the equations, frantically. Perhaps he could hire a car and driver and just take the road? But no. That might be possible by day, but at night – not a chance. Security was tightening up and down the Nile; a Westerner in a cab without a very special permit would be immediately halted at the edge of town and summarily returned whence he came – that or detained and questioned. Or worse.

No, a train was the only way to get to Sohag tonight. Then he could head on to Nazlet tomorrow. And he needed to get there tonight. Because, if the reports of Sassoon’s body being rediscovered had reached Abydos, then they would have reached elsewhere, too; and other people would have reached precisely the same conclusion.

‘Haiwan!’

‘La! La!’

There were men apparently fighting at the front of the queue.

Harper abandoned any hope of getting a ticket in time. Instead he reached in the zipped pocket of his fleecy climber’s jacket – the desert night was cool, even down here in southern Egypt – and pulled out a wad of US dollars. Baksheesh might just work where patience was exhausted. He had to try, or his quest would be finished before it began.

Ryan sauntered over to the concrete arch that led onto the platforms. Like almost every official threshold in Egypt it was barred by an airport-style detector, a boxy doorway of metal: a detector that served no purpose as it wasn’t plugged in.

But the security guard was real enough. He eyed Harper. ‘Men fethlek? Aiwa? Tick-et!’

The voice was curt; this was far from promising. But Harper had no choice. Subtly as he could, he offered a twenty-buck note – a day’s wage – to the security guard, folded between his fingers.

The guard glanced for a moment at the money, then clasped the cash with a practised grace, like a concierge at the Carlyle, and ushered Ryan through.

He was on the platform. Now the train.

There!

The train was pulling out. Barging past some smoking soldiers, he reached for the receding metal handle, but it slipped from his grasp.

Now the train was really grinding into life – and speeding up. He wasn’t going to make it; but this was the last train of the night so he had to make it! Breaking into a sprint, he jumped and tried again, and at the edge of his strength he grabbed the escaping handle, swung himself violently in through the open door, and with all the strength of a decade of carrying rocks, somehow tugged himself and his rucksack safely inside.

He was in the train. He was in. He’d done it! There was an advantage to being a peasant who hodded mud bricks in the sun. It made you fit and strong.

The Nileside express hooted merrily, as if in appreciation of Ryan’s gymnastic achievement. Then it accelerated out of Abydos, past a straggling Muslim cemetery, past the last neon-lit minarets, spearing the darkness, and then the cooler air told him he was inthe Nilotic countryside.

For two hours he stood in the vestibule between the toilet and the broken carriage door, waiting, nervously, for the collector, dollars for baksheesh in hand. Yet the collector didn’t even show up.

The chaos of Egypt could sometimes be beneficial.

Only the tea-boy interrupted the rattling journey down the Nile valley, carrying a silver tray of little glasses as he patrolled the carriages, calling out, ‘Shay, shay, shay!’

Harper bought a cup of black tea, heavily sugared.

‘Sefr, men fadlak …’

Gratefully, he sank the tea, then chased it with mineral water, as he opened his notebook and examined the scribbled document that Hassan had given him before he’d departed Abydos. The name was written in Latin letters as well as Arabic:

MOHAMMAD KHATTAB.

The head of police in Nazlet, and a cousin of Hassan’s. The fact he was related to Hassan came as no surprise to Ryan. Everyone who ascended through the bureaucracy of provincial Egypt – from the police to the army to the civil service – did so because they were related in some complex manner to someone else.

‘Shukran.’ He handed the tea-glass back to the tea-boy, who had returned to collect the empties. The drained glasses chinked on their steel tray as the train switchbacked, closing in on Sohag. The boy steadied himself, and his tray, and pressed on.

‘Shay! Shay! Shay!’

Harper looked at the note again. The rest of it was in Arabic, which he could barely read, even though he spoke it pretty well. But Harper knew the contents: Hassan had already explained. It told the director of the Nazlet police that Ryan was mightily important and a great friend of Egypt, and Hassan of Abydos would be lavishly grateful if any assistance could be offered to his VIP American acquaintance.

Exactly what that assistance might be, how the hell he was going to get his hands on the Sokar documents, and how he was going to stop others from doing the same, Ryan did not know. But he was going to give it his best shot. His last shot. Late in the day, he’d been offered a break and he was going to take it. For his wife. For Victor. But mainly for himself. After ten years of giving everything to Egypt, a little selfish ambition was excusable. Wasn’t it?

The train hooted in the dark, and this was accompanied by the squeal of its brakes: the dusty yellow stain in the midnight sky confirmed that Sohag was near. He’d made it as quickly as he could in the circumstances. Would this be the crucial factor?

Quite possibly. The body of his old tutor had only been discovered yesterday. Harper might just be the first person on the scene with a real sense of what treasures could be contained in the bag found on Sassoon’s body.

A row of shuttered shops flickered under dirty streetlights. The train clattered, and then halted, with a juddering wrench.

The station forecourt was chaotic. This time Ryan gave up any pretence at politeness and shunted his way through the mêlée. And as soon as he reached the street, he accepted the first offer of a cab – Jayed! – chucked his rucksack in the back seat, and sat in the front, like an Egyptian, alongside the driver.

Another half a mile brought them to the biggest hotel in town: an ugly concrete tower that loomed over the elegant eternity of the Nile in a forbidding manner. As he checked in, Ryan wondered if Sassoon had stayed here, during his final nights alive on this earth.

The night passed fitfully. Barges hooted on the Nile. His room smelled of toilet but the toilet smelled of woodsmoke. He tried to sleep but had bad dreams, for the first time in years. Dreams of his dead wife mixed with dreams of dogs, headless dogs, running down canal towpaths. Endless, sweaty, malarial dreams that made Ryan all too ready for morning: he rose before his alarm.

As the first pink intimation of day tinted the horizon he was already dressed and hailing another taxi.

The drive to Nazlet took several hours. By the time he reached the impossibly rural remoteness of the desolate town on the very edge of very serious desert, it was noon and fiercely hot. Dogs lay whimpering in the shade of the biblical palm trees.

He had to find the police station.

A handsome youth in a clean djellaba, riding a Japanese dirt-bike, was negotiating his way down the rutted road, avoiding heaps of camel dung. Ryan waved him over. The lad pulled up and stared, in blatant astonishment, at a Western face. Presumably Nazlet saw very few Euro-American visitors: maybe none. This was about as remote as settlements got on the frontiers of Middle and Upper Egypt.

Ryan asked in his clearest, slowest Arabic where the police station could be found.

The boy paused. Then he answered, in Arabic, ‘Not far, half a kilometre past the old houses. Just up there.’

‘Thank you.’

The youth nodded, and smiled his handsome white smile, then kick-started his bike again. As he drove off he shouted, ‘But be careful. They are arresting everyone!’

This gave Ryan serious pause. Arrests? What could he do? Maybe he should go back to Sohag and wait. But that was absurd: he had come this far, and he was so near. The Sokar Hoard was within his grasp: he could sense it.

Resolved, Ryan turned. And saw a policeman.

The cop was standing three metres away. With a gun. Pointing at Ryan’s chest.

‘Come with me.’

13

Museum of Witchcraft, Boscastle, Cornwall

‘Roasted cats?’

‘Yes.’

‘Hmmm.’

The owner of the museum paused, staring thoughtfully into space. Above him was a decorative wooden sign saying: THE MOST FAMOUS MUSEUM OF WITCHCRAFT IN THE WORLD.

Karen Trevithick would normally have dismissed this as tourist-attracting whimsy, or indeed as bullshit, but everyone she had spoken to had assured her: No, go there, the guy who owns the place really knows his stuff. The museum is serious.

So she had made the long drive to the beautiful stormy cliffs of far-north Cornwall and the fishing village of Boscastle, sequestered in a cove between those cliffs, staring out at the furious waves that attacked the stone harbour. The day was blustery and bright, and very cold. The village still had its Christmas lights dangling across the wet and narrow cobbled roads; they looked melancholy now Christmas was over.

Karen was glad when Donald Ryman, the late-middle-aged owner, closed the door to the salt-scented air, silencing the seagulls.

Again he stared at nothing, then he turned. ‘Let’s go into the museum, and think about cats. Roasted cats, yes, a little strange.’

Another door led into the museum proper; a series of small, low ceilinged rooms: fishermen’s cottages knocked together. There was a big glass box in front of Karen: inside was a perpendicular stuffed goat wearing a dark scarlet robe.

‘The goat of Mendes,’ said Donald. ‘An avatar of Satan, the Horned God, worshipped for thousands of years.’ He pointed at a large rack of little glass jars, some full of vegetable matter, some containing ghastly wax dolls; naked, grimacing figurines. ‘These are herbs for witchcraft, the real thing. Gerald Gardner collected them decades ago. The wax figurines are poppets, little models of people for sticking pins in, to cause injury or death.’

She waited for an explanation but Donald’s eyes were now fixed on something over her shoulder. She turned to see what he was looking at. The exhibits were many: a dried old stoat, a hag stone for cursing, a rabbit’s heart pierced with a thorn – and a stuffed cat, chasing a stuffed rat.

He gestured at the mangy old stuffed cat. ‘Taghairm! Yes, yes. Taghairm!’

‘What?’

‘I believe what you witnessed was Taghairm! A truly ghastly ritual, often associated with the Celts, especially in Scotland.’

Karen gazed at the cat, as Donald went on, ‘Cats, why didn’t I think of this before? Yes! Cats are so important to magic. In medieval England cats would be buried alive in walls, as charms against rats or mice. These are surprisingly common – they come as a nasty surprise to homeowners, ah, renovating their lovely period cottage. A dead cat in the walls!’ He chuckled. ‘Cats are intrinsic to magical ritual. The idea of them as creatures of supernatural power dates back to Egyptian times, of course. The Egyptians worshipped the cat. The fear and veneration of cats has continued ever since.’

‘Taghairm? What is that?’

He was interesting but her time was short: they had a suicide now, a dead body, linked to the atrocious ritual on Zennor Hill. Speed the case.

‘Sorry, witchcraft is my passion, I can be a little discursive. Taghairm is a Celtic rite also known as “giving the Devil his supper”. It’s a ceremony where a series of cats is burned alive, one after the other, sometimes over a period of days. The animals would be roasted on, ah, spits, or drenched in liquors and oils and burned that way.’

‘But why?’

‘To summon the Devil! Or least a highly important demon. It was believed that the horrendous shrieking of the cats would disturb the Devil, and invoke him, and eventually he would be forced to reveal himself and do the bidding, at least temporarily, of the coven or the wizard.’

A ritual for summoning the Devil? Karen walked around the darkened rooms with their glass cabinets and their morbid contents: a naked mandrake in a jar, inscribed with a screaming face; a knitted poppet woven with real human hair and stuck with a vicious pin; a medieval wooden carving of a woman tearing open her vagina, leering. The silence was claustrophobic. She turned to look at Donald, who was sorting through some keys.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.