Полная версия

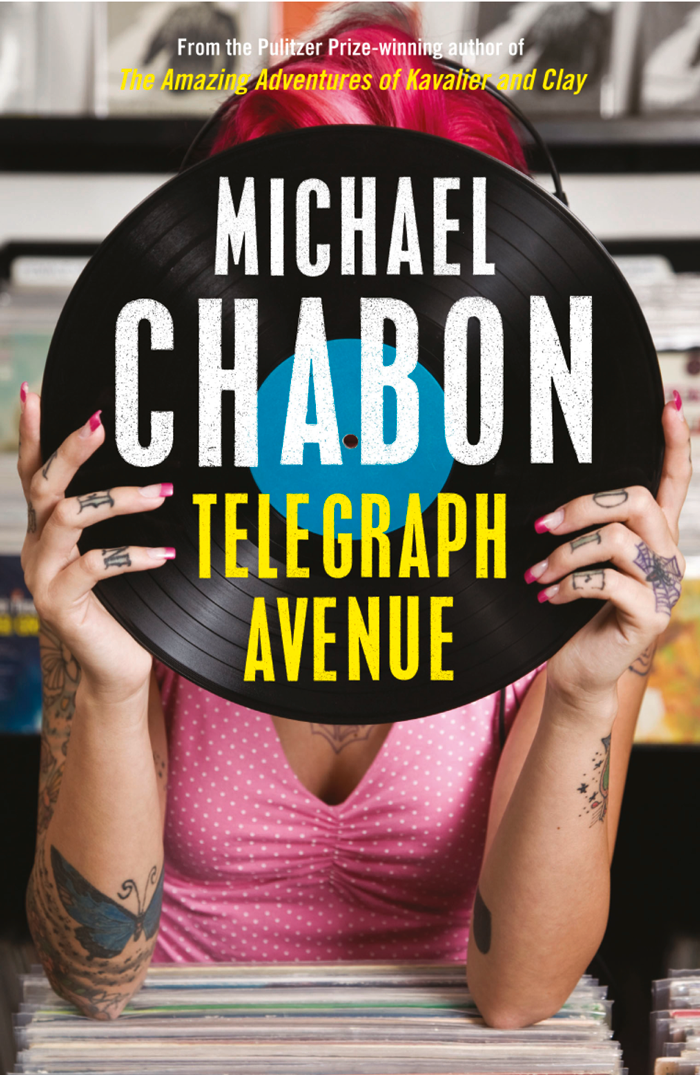

Telegraph Avenue

Telegraph Avenue

A Novel

Michael Chabon

Dedication

To Ayelet, from the drop of the needle to the innermost groove

Epigraph

Call me Ishmael.

—Ishmael Reed, probably.

Contents

Dedication

Epigraph

I

Dream of Cream

II

The Church of Vinyl

III

A Bird of Wide Experience

IV

Return to Forever

V

Brokeland

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Michael Chabon

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

I

Dream of Cream

A white boy rode flatfoot on a skateboard, towed along, hand to shoulder, by a black boy pedaling a brakeless fixed-gear bike. Dark August morning, deep in the Flatlands. Hiss of tires. Granular unraveling of skateboard wheels against asphalt. Summertime Berkeley giving off her old-lady smell, nine different styles of jasmine and a squirt of he-cat.

The black boy raised up, let go of the handlebars. The white boy uncoupled the cars of their little train. Crossing his arms, the black boy gripped his T-shirt at the hem and scissored it over his head. He lingered inside the shirt, in no kind of hurry, as they rolled toward the next pool of ebbing streetlight. In a moment, maybe, the black boy would tug the T-shirt the rest of the way off and fly it like a banner from his back pocket. The white boy would kick, push, and reach out, feeling for the spark of bare brown skin against his palm. But for now the kid on the skateboard just coasted along behind the blind daredevil, drafting.

Moonfaced, mountainous, moderately stoned, Archy Stallings manned the front counter of Brokeland Records, holding a random baby, wearing a tan corduroy suit over a pumpkin-bright turtleneck that reinforced his noted yet not disadvantageous resemblance to Gamera, the giant mutant flying tortoise of Japanese cinema. He had the kid tucked up under his left arm as, with his free right hand, he worked through the eighth of fifteen crates from the Benezra estate, the records in crate number 8 favoring, like Archy, the belly meat of jazz, salty and well marbled with funk. Electric Byrd (Blue Note, 1970). Johnny Hammond. Melvin Sparks’s first two solo albums. Charles Kynard, Wa-Tu-Wa-Zui (Prestige, 1971). As he inventoried the lot, Archy listened, at times screwing up his eyes, to the dead man’s minty quadrophonic pressing of Airto’s Fingers (CTI, 1972) played through the store’s trusty Quadaptor, a sweet gizmo that had been hand-dived from a Dumpster by Nat Jaffe and refurbished by Archy, a former army helicopter electrician holding 37.5 percent—last time he’d bothered to check—of a bachelor’s in electrical engineering from SF State.

The science of cataloging one-handed: Pluck a record from the crate, tease the paper sleeve out of the jacket. Sneak your fingers into the sleeve. Waiter the platter out with your fingertips touching nothing but label. Angle the disc to the morning light pouring through the plate window. That all-revealing, even-toned East Bay light, keen and forgiving, always ready to tell you the truth about a record’s condition. (Though Nat Jaffe claimed it was not the light but the window, a big solid plate of Pittsburgh glass vaccinated against all forms of bullshit during the period of sixty-odd years when the space currently housing Brokeland Records had been known as Spencer’s Barbershop.)

Archy swayed, eyes closed, grooving on the heft of the baby, on the smell of grease coming off of Ringo Thielmann’s bass line, on the memory of the upraised eyes of Elsabet Getachew as she gave him head yesterday in the private dining room of the Queen of Sheba Ethiopian restaurant. Recollecting the catenary arch of her upper lip, the tip of her tongue going addis ababa along the E string of his dick. Swaying, grooving, feeling on that Saturday morning, just before the boots of the neighborhood tracked bad news through his front door, like he could carry on that way all day, forever.

“Poor Bob Benezra,” Archy said to the random baby. “I did not know him, but I feel sorry for him, leaving all these beautiful records. That’s how come I have to be an atheist, right there, Rolando, seeing all this fine vinyl the poor man had to leave behind.” The baby not too young to start knowing the ledge, the cold truth, the life-and-death facts of it all. “What kind of heaven is that, you can’t have your records?”

The baby, understanding perhaps that it was purely rhetorical, made no attempt to answer this question.

Nat Jaffe showed up for work under a cloud, like he did maybe five times out of eleven or, be generous, call it four out of every nine. His bad mood a space helmet lowered over his head, poor Nat trapped inside with no way to know whether the atmosphere was breathable, no gauge to tell him when his air supply would run out. He rolled back the deadbolt, keys banging against door, working one-handed himself, because of a crate of records he had crooked up under his left arm. Nat bulled in with his head down, humming low to himself; humming the interesting chord changes to an otherwise lame-ass contemporary pop song; humming an angry letter to the slovenly landlord of the nail salon two blocks up, or to the editor of the Oakland Tribune whose letters page his anger often adorned; humming the first fragments of a new theory of the interrelationship between the bossa nova and the nouvelle vague; humming even when he wasn’t making a sound, even when he was asleep, some wire deep in the bones of Nathaniel Jaffe always resounding.

He closed the door, locked it from the inside, set the crate on the counter, and hung his gray-on-charcoal pin-striped fedora from one of nine double-branched steel hooks that also dated from the days of Spencer’s Barbershop. He ran a finger through his dark hair, kinked tighter than Archy’s, thinning at the hairline. He turned, straightening his necktie—hepcat-wide, black with silver flecks—taking note of the state of box 8. Working his head around on the neck joints a few times as if in that creak of bones and tension lay hope of release from whatever was causing him to hum.

He walked to the back of the store and disappeared through the beaded curtain, laboriously painted by Nat’s son, Julie, with the image of Miles Davis done up as a Mexican saint, St. Miles’s suffering heart exposed, tangled with a razor wire of thorns. Not a perfect likeness, to be sure, looking to Archy more like Mookie Wilson, but it could not be easy to paint a portrait of somebody across a thousand half-inch beads, and few besides Julius Jaffe would ever contemplate doing it, let alone give it a try. A minute later Archy heard the toilet flush, followed by a spasm of angry coughing, and then Julie’s father came back out to the front of the store, ready to burn another day.

“Whose baby is that?” he said.

“What baby?” said Archy.

Nat unbolted the front door and spun the sign to inform the world that Brokeland was open for business. He gave his skull another tour of the top of his spinal column, hummed some more, coughed again. Turned to his partner, looking almost radiant with malice. “We’re totally fucked,” he said.

“Statistically, that’s indeed likely,” Archy said. “In this case, how so?”

“I just came from Singletary.”

Their landlord, Mr. Garnet Singletary, the King of Bling, sold grilles and gold finger rings, rope by the yard, three doors up from Brokeland. He owned the whole block, plus a dozen or more other properties spread across West Oakland. Retail, commercial. Singletary was an information whale, plying his migratory route through the neighborhood, taking in all the gossip, straining it for nutrients through his tireless baleen. He had never once turned loose a dollar to frolic among the record bins at Brokeland, but he was a regular customer nonetheless, stopping by every couple of days just to audit. To monitor the balance of truth and bullshit in the local flow.

“Yeah?” Archy said. “What’d Singletary have to say?”

“He said we’re fucked. Seriously, why are you holding a baby?”

Archy looked down at Rolando English, a rusty young man with a sweet mouth and soft brown ringlety curls all sweaty and stuck to the side of his head, stuffed into a blue onesie, then wrapped in a yellow cotton blanket. Archy hefted Rolando English and heard a satisfying slosh from inside. Rolando English’s mother, Aisha, was a daughter of the King of Bling. Archy had offered to take Rolando off Aisha’s hands for the morning, maybe pick up a few items the baby required, and so forth. Archy’s wife was expecting their first child, and it was Archy’s notion that, given the imminence of paternity, he might get in some practice before the first of October, their due date, maybe ease the shock of finding himself, at the age of thirty-six, a practicing father. So he and Rolando had made an excursion up to Walgreens, Archy not at all minding the walk on such a fine August morning. Archy dropped thirty dollars of Aisha’s money on diapers, wipes, formula, bottles, and a package of Nuk nipples—Aisha gave him a list—then sat down right there on the bus bench in front of the Walgreens, where he and Rolando English changed themselves some foul-smelling diaper, had a little snack, Archy working his way through a bag of glazed holes from the United Federation of Donuts, Rolando English obliged to content himself with a pony of Gerber Good Start.

“This here’s Rolando,” Archy said. “I borrowed him from Aisha English. So far he doesn’t do too much, but he’s cute. Now, Nat, I gather from one or two of your previous statements that we are fucked in some manner.”

“I ran into Singletary.”

“And he gave you some insight.”

Nat spun the crate of records he had carried in with him, maybe thirty-five, forty discs in a Chiquita crate, started idly flipping through them. At first Archy assumed Nat was bringing them in from home, items from his own collection he wanted to sell, or records he had taken home for closer study, the boundaries among the owners’ respective private stocks and the store’s inventory being maintained with a careless exactitude. Archy saw that it was all just volunteers. A Juice Newton record, a bad, late Commodores record, a Care Bears Christmas record. Trash, curb fruit, the bitter residue of a yard sale. Orphaned record libraries called out constantly to the partners from wherever fate had abandoned them, emitting a distress signal only Nat and Archy could hear. “The man could go to Antarctica,” Aviva Roth-Jaffe once said of her husband, “and come back with a box of wax 78s.” Now, hopeless and hopeful, Nat sifted through this latest find, each disc potentially something great, though the chances of that outcome diminished by a factor of ten with each decrease in the randomness of the bad taste of whoever had tossed them out.

“‘Andy Gibb,’” Nat said, not even bothering to freight the words with contempt, just slipping ghosts of quotation marks around the name as if it were a known alias. He pulled out a copy of After Dark (RSO, 1980) and held it up for Rolando English’s inspection. “You like Andy Gibb, Rolando?”

Rolando English seemed to regard the last album released by the youngest Gibb brother with greater open-mindedness than his interlocutor.

“I’ll go along with you on the cuteness,” Nat said, his tone implying that he would go no further than that, like he and Archy had been having an argument, which, as far as Archy could remember, they had not. “Give him.”

Archy passed the baby to Nat, feeling the cramp in his shoulder only after he had let go. Nat encircled the baby under the arms with both hands and lifted him, going face-to-face, Rolando English doing a fine job of keeping his head up, meeting Nat’s gaze with that same air of willingness to cut people a break, Andy Gibb, Nat Jaffe, whomever. Nat’s humming turned soft and lullaby-like as the two considered each other. Baby Rolando had a nice, solid feel to him, a bunch of rolled socks stuffed inside one big sock, dense and sleepy, not one of those scrawny flapping-chicken babies one ran across from time to time.

“I used to have a baby,” Nat recalled, sounding elegiac.

“I remember.” That was back around the time he first met Nat, playing a wedding at that Naturfreunde club up on Joaquin Miller. Archy, just back from the Gulf, came in at the last minute, filling in for Nat’s regular bassist at the time. Now the former Baby Julius was fifteen and, to Archy at least, more or less the same sweet freakazoid as always. Hearing secret harmonies, writing poetry in Klingon, painting his fingernails with Jack Skellington faces. Used to go off to nursery school in a leotard and a tutu, come home, watch Color Me Barbra. Even at three, four years old, prone like his father to holding forth. Telling you how french fries didn’t come from France or German chocolate from Germany. Same tendency to get caught up in the niceties of a question. Lately, though, he seemed to spend a lot of time transmitting in some secret teenager code, decipherable only by parents, designed to drive them out of their minds.

“Babies are cool,” Nat said. “They can do Eskimo kisses.” Nat and Rolando went at it, nose to nose, the baby hanging there, putting up with it. “Yeah, Rolando’s all right.”

“That’s what I thought.”

“Got good head control.”

“Doesn’t he, though?” Archy said.

“That’s why they call him Head-Control Harry. Right? Sure it is. Head-Control Harry. You want to eat him.”

“I guess. I don’t really eat babies all that much.”

Nat studied Archy the way Archy had studied the A-side of the late Bob Benezra’s copy of Kulu Sé Mama (Impulse!, 1967), looking for reasons to grade it down.

“So, what, you practicing? That the idea?”

“That was the idea.”

“And how’s it working out?”

Archy shrugged, giving it that air of modest heroism, the way you might shrug after you had been asked how in God’s name you managed to save a hundred orphans trapped in a flaming cargo plane from collision with an asteroid. As he played it off to Nat, Archy knew—felt, like the baby-shaped ache in his left arm—that neither his ability nor his willingness to care for Rolando English for an hour, a day, a week, had anything whatsoever to do with his willingness or ability to be a father to the forthcoming child now putting the finishing touches on its respiratory and endocrine systems in the dark laboratory of his wife’s womb.

Wiping a butt, squeezing some Carnation through a nipple, mopping up the milk puke with a dishrag, all that was mere tasks and procedures, a series of steps, the same as the rest of life. Duties to pull, slow parts to get through, shifts to endure. Put your thought processes to work on teasing out a tricky time signature from On the Corner (Columbia, 1972) or one of the more obscure passages from The Meditations (Archy was currently reading Marcus Aurelius for the ninety-third time), sort your way one-handed through a box of interesting records, and before you knew it, nap time had arrived, Mommy had come home, and you were free to go about your business again. It was like the army: Be careful, find a cool dry place to stash your mind, and hang on until it was over. Except, of course (he realized, experiencing the full-court press of a panic that had been flirting with him for months, mostly at three o’clock in the morning when his wife’s restless pregnant tossing disturbed his sleep, a panic that the practice session with Rolando English had been intended, vainly, he saw, to alleviate), it never would be over. You never would get through to the end of being a father, no matter where you stored your mind or how many steps in the series you followed. Not even if you died. Alive or dead or a thousand miles distant, you were always going to be on the hook for work that was neither a procedure nor a series of steps but, rather, something that demanded your full, constant attention without necessarily calling on you to do, perform, or say anything at all. Archy’s own father had walked out on him and his mother when Archy was not much older than Rolando English, and even though, for a few years afterward, as his star briefly ascended, Luther Stallings still came around, paid his child support on time, took Archy to A’s games, to Marriott’s Great America and whatnot, there was something further required of old Luther that never materialized, some part of him that never showed up, even when he was standing right beside Archy. Fathering imposed an obligation that was more than your money, your body, or your time, a presence neither physical nor measurable by clocks: open-ended, eternal, and invisible, like the commitment of gravity to the stars.

“Yeah,” Nat said. For a second the wire in him went slack. “Babies are cute. Then they grow up, stop taking showers, and beat off into their socks.”

There was a shadow in the door glass, and in walked S. S. Mirchandani, looking mournful. And the man had a face that was built for mourning, sag-eyed, sag-jowled, lamentation pooling in the spilt-ink splash of his beard.

“You gentlemen,” he said, always something elegiac and proper in his way of speaking the Queen’s English, some remembrance of a better, more civilized time, “are fucked.”

“I keep hearing that,” Archy said. “What happened?”

“Dogpile,” Mr. Mirchandani said.

“Fucking Dogpile,” Nat agreed, humming again.

“They are breaking ground in one month’s time.”

“One month?” Archy said.

“Next month! This is what I am hearing. Our friend Mr. Singletary was speaking to the grandmother of Mr. Gibson Goode.”

Nat said, “Fucking Gibson Goode.”

Six months prior to this morning, at a press conference with the mayor at his side, Gibson “G Bad” Goode, former All-Pro quarterback for the Pittsburgh Steelers, president and chairman of Dogpile Recordings, Dogpile Films, head of the Goode Foundation, and the fifth richest black man in America, had flown up to Oakland in a customized black-and-red airship, brimming over with plans to open a second Dogpile “Thang” on the long-abandoned Telegraph Avenue site of the old Golden State market, two blocks south of Brokeland Records. Even larger than its giant predecessor near Culver City, the Oakland Thang would comprise a ten-screen cineplex, a food court, a gaming arcade, and a twenty-unit retail galleria anchored by a three-story Dogpile media store, one floor each for music, video, and other (books, mostly). Like the Fox Hills Dogpile store, the Oakland flagship would carry a solid general-interest selection of media but specialize in African-American culture, “in all,” as Goode put it at the press conference, “its many riches.” Goode’s pockets were deep, and his imperial longings were married to a sense of social purpose; the main idea of a Thang was not to make money but to restore, at a stroke, the commercial heart of a black neighborhood cut out during the glory days of freeway construction in California. Unstated during the press conference, though inferable from the way things worked at the L.A. Thang, were the intentions of the media store not only to sell CDs at a deep discount but also to carry a full selection of used and rare merchandise, such as vintage vinyl recordings of jazz, funk, blues, and soul.

“He doesn’t have the permits and whatnot,” Archy pointed out. “My boy Chan Flowers has him all tangled up in environmental impacts, traffic studies, all that shit.”

The owner and director of Flowers & Sons funeral home, directly across Telegraph from the proposed Dogpile site, was also their Oakland city councilman. Unlike Singletary, Councilman Chandler B. Flowers was a record collector, a free-spending fiend, and without fully comprehending the reasons for his stated opposition to the Dogpile plan, the partners had been counting on it, clinging to the ongoing promise of it.

“Evidently something has changed the Councilman’s mind,” said S. S. Mirchandani, using his best James Mason tone: arch and weary, hold the vermouth.

“Huh,” Archy said.

There was nobody in West Oakland more hard-ass or better juiced than Chandler Flowers, and the something that evidently had changed his mind was not likely to have been intimidation.

“I don’t know, Mr. Mirchandani. Brother has an election coming,” Archy said. “Barely came through the primary. Maybe he’s trying to stir up the base, get them a little pumped. Energize the community. Catch some star power off Gibson Goode.”

“Certainly,” said Mr. Mirchandani, his eyes saying no way. “I am sure there is an innocent explanation.”

Kickbacks, he was implying. A payoff. Anybody who managed, as Mr. Mirchandani did, to keep a steady stream of cousins and nieces flowing in from the Punjab to make beds in his motels and wash cars at his gas stations without running afoul of the authorities at either end, was likely to find his thoughts running along those lines. It was almost as hard for Archy to imagine Flowers—that stiff-necked, soft-spoken, and everlastingly correct man, a hero in the neighborhood since Lionel Wilson days—taking kickbacks from some showboating ex-QB, but then Archy tended to make up for his hypercritical attitude toward the condition of vinyl records by going too easy on human beings.

“Anyways, it’s too late, right?” Archy said. “Deal already fell through. The bank got cold feet. Goode lost his financing, something like that?”

“I don’t really understand American football,” said S. S. Mirchandani. “But I am told that when he was a player, Gibson Goode was quite famous for something called ‘having a scramble.’”

“The option play,” Nat said. “For a while there, he was pretty much impossible to sack.”

Archy took the baby back from Nat Jaffe. “G Bad was a slippery motherfucker,” he agreed.

Mr. Nostalgia, forty-four, walrus mustache, granny glasses, double-extra-large Reyn Spooner (palm trees, saw grass, woodies wearing surfboards), stood behind the Day-Glo patchwork of his five-hundred-dollar exhibitor’s table, across a polished concrete aisle and three tables down from the signing area, under an eight-foot vinyl banner that read MR. NOSTALGIA’S NEIGHBORHOOD, chewing on a Swedish fish, unable to believe his fucking eyes.

“Yo!” he called out as the goon squad neared his table: two beefy white security guys in blue poly blazers and a behemoth of a black dude, Gibson Goode’s private muscle, whose arms in their circumference were a sore trial to the sleeves of his black T-shirt. “A little respect, please!”

“Damn right,” said the man they were escorting from the hall, and as they came nearer, Mr. Nostalgia saw that it really was him. Thirty years too old, twenty pounds too light, forty watts too dim, maybe: but him. Red tracksuit a size too small, baring his ankles and wrists. Jacket waistband riding up in back under a screened logo in yellow, a pair of upraised fists circled by the words BRUCE LEE INSTITUTE, OAKLAND, CA. Long and broad-shouldered, with that spring in his gait, coiling and uncoiling. Making a show of dignity that struck Mr. Nostalgia as poignant if not successful. Everybody staring at the guy, all the men with potbellies and back hair and doughy white faces, heads balding, autumn leaves falling in their hearts. Looking up from the bins full of back issues of Inside Sports, the framed Terrible Towels with their bronze plaques identifying the nubbly signature in black Sharpie on yellow terry cloth as that of Rocky Bleier or Lynn Swann. Lifting their heads from the tables ranged with rookie cards of their youthful idols (Pete Maravich, Robin Yount, Bobby Orr), with canceled checks drawn on long-vanished bank accounts of Ted Williams or Joe Namath; unopened cello packs of ’71 Topps baseball cards, their fragile black borders pristine as memory, and of ’86 Fleer basketball cards, every one holding a potential rookie Jordan. Watching this big gray-haired black man they half-remembered, a face out of their youth, get the bum’s rush. That’s the dude from the signing line. Was talking to Gibson Goode, got kind of loud. Hey, yeah, that’s what’s-his-face. Give him credit, the poor bastard managed to keep his chin up. The chin—him, all right—with the Kirk Douglas dimple. The light eyes. The hands, Jesus, like two uprooted trees.