Полная версия

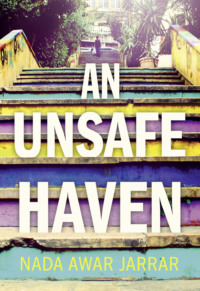

Somewhere, Home

She thought back to Thursday nights when her mother wore a long white veil of Damascene silk wrapped tightly round her head, covering her soft hair and showing only familiar eyes. ‘I’m going to the prayer reading,’ she would tell the children through silk. ‘You may sit outside and listen. Quietly, children.’ They would sit and stare at the rows of polished shoes arranged neatly outside the prayer room beside Grandfather’s grave. It was there Saeeda committed the most magnificent act of defiance of her life. Sneaking past her waiting brothers, she grabbed an armful of shoes and threw them across the garden before reaching out for more. Then, cheeks flushed and eyes sparkling, she turned from her staring brothers, laughing loudly, her head flung back, and ran away. She was married a year later.

When her in-laws died, Saeeda returned home to live with Alia and Ameen, and at twenty-eight prepared once again to put the comfort of others before her own. She watched the two people who, one in her presence and the other in his absence, had shaped her life and loved them with the same intensity she had as a child, the anxiety she had once felt turning into insistent tenderness. She took over the running of the house, working quickly and quietly, her efforts imperceptible, mindful of her parents as she might have been of the children she never had.

Alia did not know what to do with the woman Saeeda had become. She would watch her daughter doing the housework and prepare to criticize a mattress unturned or a floor left unswept when something would stop her and the words refused to make themselves heard. In time, Alia realized that her heart had begun to dictate her actions. The tears that doctors told her were the result of the stroke she had suffered came to her without warning, trickling down to the taste of salt in her mouth. If Saeeda noticed her mother’s sadness, she did not comment on it, discreetly handing the older woman a handkerchief and then moving on to something else.

Saeeda’s attachment to her father grew as he became older and more vulnerable. Whenever he complained of pain in his arthritic hands, she would pour a spoonful of olive oil into her own and gently massage it into his long fingers, rubbing slowly at the swollen joints and humming a quiet tune to soothe him. Once, as she reached out to take his hand, he lifted it, placed it lightly on her face and smiled with such sweetness that Saeeda thought her heart would drop.

‘Are you alright, Father?’ she asked him.

‘You’re a good child,’ he whispered in his old man’s voice. ‘A good child.’

When Ameen died, Saeeda had just turned forty-two. She was rounder than she had once been, but her black eyes still betrayed hope and the rosy white complexion that had always been her only claim to beauty had not withered. Her mother was by then feeble.

Saeeda’s brothers insisted on bringing in a middle-aged widow from a nearby village to help care for Alia.

With extra time on her hands, Saeeda decided to tend to the long-neglected garden of the family home. She began by clearing it of the debris that had accumulated over the years, making way for the herb and flower beds she planned for, and raking the pebbles out of the earth. She scrubbed the floor of the terrace clean until the criss-cross pattern on the tiles that covered it shone in the sun, and had the iron balustrade around its edges painted with the same dark-green colour as the front door. She planted a clinging vine that would climb up the balustrade and enclose the terrace in green. Then she placed tall yellow rose bushes at the end of the garden overlooking the souq, and pink and red geraniums just behind them where they could be seen from the terrace.

But it was the herb garden that Saeeda was most proud of, a small square plot just outside the kitchen door, which she filled with basil and thyme, parsley, mint, rosemary and coriander, everything she loved to touch and smell and taste in her cooking. She spent so much time tending this part of the garden that the heady scents seeped into her clothes and skin, and stayed there so that she only had to lift her hands to her face and the smell of fresh basil mixed with the sharpness of parsley, mint and the exotic aroma of thyme and coriander would fill her nostrils.

Villagers said that it was the fragrance emanating from that herb garden that lured the stranger to Saeeda’s doorstep one summer afternoon. He carried a large sack of unshelled peanuts in one hand, a gray felt fedora in the other.

Saeeda and Alia had been sitting on the terrace in the imperfect shade of the still young vine, sipping aniseed tea in silence. Saeeda put down her cup and walked up to the man. He was small, thin and had the kind of face that from a distance seems familiar. She thought at first that he had lost his way, until he asked to see her father.

‘My father passed away over a year ago,’ Saeeda said, shaking her head.

‘May the loss be compensated in your own life.’ He paused before adding, ‘I once worked with your father in Africa. I wanted so much to see him and thank him for all he did for me.’

Khaled came from a small village across the mountain. Returning home after a twenty-year absence, he carried the mystery of distant places about him that Saeeda’s father once had. She sat Khaled next to her mother, served him tea and sweetmeats, and listened to the stories of adventure Ameen had neglected to tell her and her brothers. When he left some time later, the two women made their way into the house and prepared for bed.

‘I never knew Father had such an exciting time of it in Africa,’ Saeeda said.

Alia grunted.

Saeeda could feel her mother’s eyes following her around the room. ‘Is everything alright, Mother?’ Saeeda turned and asked.

Alia only looked at her daughter more closely. ‘Let’s go to bed, then.’

* * *

Khaled came regularly after that, sometimes as often as three times a week, always carrying a gift for Saeeda and her mother, always with a smile on his small, angular face. Saeeda was welcoming though she did not quite understand his interest. He was nothing like her beloved brothers, all with families of their own, strong and no longer needing her or their mother. Khaled was fragile, a man whose energy seemed finally to have dissipated after years of exile and hard work. In Saeeda he seemed to find the pause from activity that he needed, the quietness of a resigned existence. They sometimes spoke for hours, Khaled telling her of his years in Africa, Saeeda recounting stories of her childhood. At others they would sit in silence, watching the movement of the village around them and fussing over Alia if she sat with them.

Saeeda began to look forward to Khaled’s visits, not allowing her thoughts to wander beyond them but sensing suppressed anticipation inside her nonetheless.

One evening Khaled arrived later than usual to find Alia already in bed and Saeeda preparing to follow. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said, standing at the front door. ‘I must be disturbing you.’

‘Come in, Khaled.’ Saeeda opened the door wider. ‘Come in.’ She showed him into the living room where a small side lamp cast shadows across the walls. ‘Can I get you anything?’ she asked him.

‘No, no, please. I just want to talk to you.’

Saeeda sat down and looked closely at Khaled. Suddenly she felt uneasy.

‘We are friends, you and I, aren’t we?’ he began.

She nodded.

‘I feel I can tell you anything and you would understand.’

Saeeda smiled.

‘They want me to get married!’

‘They?’

‘The family. There’s a cousin from our village, they want me to marry her . . .’ He got up and began pacing up and down the room.

Saeeda’s heart raced and her eyes followed his every movement.

‘They don’t know,’ Khaled continued. He turned and looked straight at her. ‘I already have a family back there. I told you about it, didn’t I?’ he said. ‘We never married. She is African.’

Saeeda shook her head in disbelief and continued to stare at Khaled.

‘I left her and the children, thinking I would be able to stay away,’ he said, sitting down next to her. ‘Your father knew about it. He understood, was so kind.’ He started to cry.

Saeeda reached for him and then pulled her hand away. She was surprised at how angry she was.

Khaled looked up at her and opened his eyes wide when he saw the look on her face. ‘I thought you would understand, Saeeda.’

She folded her arms over her heart. ‘We can’t all be loved the way we want to be.’

His once fine face seemed suddenly ungenerous and pinched. She looked away.

‘I’m sorry. I just came to let you know, I’m leaving the country next week. You won’t see me again.’

The next day Saeeda was clearing up in the kitchen after lunch. When Alia got up from the table, Saeeda turned to her. ‘Mother, what do you say we take the tea out on the terrace?’

The air was fresh and a subtle breeze lifted the green vine leaves into a gentle flutter. The two women settled themselves on the old sofa. Saeeda leaned over and poured the tea. She handed her mother a cup and took one for herself. It was that quiet hour between day and sunset, when village life seemed to float as if on an afterthought.

Saeeda felt a sudden impatience. ‘Did you love my father?’ she asked her mother.

Alia stared back at her. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Just that. Did you love your husband, Mother?’

‘In those days no one talked about love,’ Alia replied firmly. ‘I saw little of Ameen through most of our marriage, until he turned old and needed me to care for him.’

Saeeda looked at her mother and felt a deep, wide anger moving through her body. She had a sudden urge to get up and run, anywhere, away from her mother’s indifference, beyond the house and the village and everything she had ever known. ‘Did you at least miss him?’ she asked, trying to keep her voice even.

Alia put her cup down, bent her head and placed her hands in her lap. When she looked up, her face had the waxed look of age all over it. ‘I wrote him a letter once, asking him to come home,’ she said with a weak smile. ‘It was after the two older boys were hurt when the school collapsed over them.’ She shook her head and looked past Saeeda. ‘I never sent it.’

Why didn’t you let him know you needed him, Mother? Saeeda wanted to ask, until she remembered what had happened to her the night before and the enormity of her own fears.

‘Does that man want to marry you?’ Alia had recovered herself.

‘You mean Khaled?’

‘He was here last night, wasn’t he?’

‘Yes, he was.’

‘What was he thinking, coming so late?’

‘It wasn’t that late, Mother. I had been planning on staying up a little longer anyway.’

‘Does he want to marry you?’ Alia persisted.

‘No, Mother,’ Saeeda said, shaking her head. ‘I don’t love him. I don’t want to leave our home. I never have.’

Maysa

Summer

I wake to the sound of someone knocking on the front door. The early mornings are still cool and I wrap myself in a blanket before going to open the door. Wadih is standing on the terrace with a small suitcase in one hand and a large leather folder in the other. He has no jacket on. ‘Come in,’ I tell him.

He walks past me and stands in the hallway for a moment.

‘Come through here.’ I point to my room. ‘Just give me a moment to get dressed and make us some tea.’

He places his things on the floor and sits on the unmade bed.

‘Will you wait?’ I ask him.

He nods his head and looks away. This, I think to myself, is the moment I usually feel anger at his silences. I take my clothes into the bathroom and shut the door.

When I come out again, Wadih is not in the room. I run a hand through my wet hair and go into the kitchen to find him stirring a pot of flower tea, his head bent low over the fragrant steam floating from it.

‘It smells wonderful, doesn’t it? Like a garden in spring.’

‘Wonderful.’ Wadih is smiling.

‘Let’s have the tea out on the terrace,’ I say, putting cups and saucers on a tray and grabbing the biscuit box.

We carry the things outside and make ourselves comfortable on the sofa, now warm with the early morning sun. Wadih pours the tea and hands me a cup. I place it on the table, put my hands on top of my belly, feeling for our child.

‘It’s very soon, isn’t it?’ he asks, looking down at my hands.

‘I’m having it here in the house.’

‘Yes, I thought you would.’

I feel a sudden remorse. ‘There will be a doctor with the midwife in case of any problems,’ I tell him. ‘I’ve had all the tests and everything. It’s going to be alright.’

‘Did you find your stories?’ Wadih asks after a short silence.

‘Stories?’

‘Your grandmother and her family, did you find out about her? You talked about it so much, I just assumed . . .’

I had forgotten telling him. It was long ago, very soon after we met. I said I wanted to spend time on my own on the mountain to gather stories about my grandmother and her children and put them in a book to read to my own children one day.

Wadih leans forward in his seat and looks closely at me. His eyes, the lines in his handsome face are achingly familiar and I feel the urge to reach out and touch him. Instead, I stand up and pick at branches of the vine that are draped over the balustrade.

‘Are things alright in the city these days?’ I ask my husband.

‘The fighting flares up and calms down again. We manage to live during the gaps in between.’

‘I haven’t felt lonely,’ I tell him. ‘Nor have I,’ he replies. ‘I only missed you.’

I return to the sofa. ‘I missed you too,’ I say truthfully. ‘I haven’t really discovered anything new, but I’ve been trying to write my own thoughts down, my own unfocused musings.’ I laugh sheepishly and look up at him but he says nothing.

A rush of heat makes its way up into my face and I place my hands on my cheeks in an attempt to cool them. ‘That silence,’ I say, ‘that relentless, obstinate silence, it makes me feel unloved.’

Wadih gets up and goes into the house. He returns with the leather folder he brought with him, places it on the dusty tiles and unzips it open. Inside there is a small pile of white cardboard squares with drawings on them. He brings the top one to me. The drawing looks remarkably like my house except that the façade is much neater, the rooftop is even and the terrace is wider underneath the clean stone arches.

Wadih brings me the second drawing. This one is of the inside of the house. There is a bright kitchen that opens onto a large dining room, and the living room is spacious and colourful with furniture and patterned Persian carpets. ‘This is of the bedrooms,’ he says, handing me the third drawing. ‘I think we’d have to add on another bathroom, especially now the baby is coming.’

I pull at his sleeve. ‘What is this?’

‘You do want us to live here, don’t you? The house will have to be renovated so I made some preliminary drawings for you to look at before we make a final decision.’

‘Did Selma tell you to come here?’ I ask him.

He reaches out and places his hand on the back of my neck and rubs gently at my skin. ‘Does it matter now?’

I shake my head and look down at the drawings.

There is music in this house, the kind that pushes gently against the outlines of my body and makes me sway this way and that. Wadih has brought the old stereo player with him from the city and plays our favourite records in the same progression again and again every evening until I find order in anticipation and am strangely comforted.

While Wadih and the men he has hired work on the house in preparation for our child’s birth, I lie on the terrace sofa, notebook in hand and a humming between my lips. I have taken to making small illustrations in the page margins, butterflies, shining suns, flowers and geometric shapes in the same pattern as the tiles, which I fill in with the colours Wadih keeps on his desk. He is amused by the childlike drawings, though he does not ask to read the words that lie alongside them.

Occasionally, whenever Selma comes to sit outside with me and to shake her head at the noise the workers are making, she inquires about the contents of the notebook.

‘Just my thoughts, Selma,’ I reassure her. ‘Nothing important.’

Each time she seems satisfied with my answer. ‘I’ve never been one for reading, anyway.’

I feel a sudden inexplicable envy at the freedom implied in her words.

Despite the heat, there is a slight breeze blowing across the terrace when Wadih comes out to join me. I pull up my legs to make room for him to sit down and feel the baby kick through my skin and against my knees.

‘She’s very active today.’ I smile at my husband and rub my belly.

‘You’re going to have a real shock if it ends up being a boy,’ Wadih says and ruffles my hair.

I shrug my shoulders and reach for the notebook.

‘Still writing?’

I nod. ‘About my mother this time.’

‘But your mother never lived here,’ Wadih says.

‘No, but this is where they met, isn’t it?’

I can almost swear to having heard Adel’s and Leila’s voices murmuring along with mine on lonely nights in this house, but I do not mention this to Wadih.

‘What are you going to do with it when you’re done?’ he asks, pointing at the notebook.

‘I don’t know. Read the stories to our child perhaps.’

‘Yasmeena,’ Wadih says in an uncertain voice. He lifts my legs and lays them in his lap.

‘Yasmeena,’ I call into the breeze. ‘Yasmeena.’

Leila

Leila first noticed the pointed arches that framed the front of the house and thought how lovely a creeping vine would look on them, green and luscious in spring, red and gold in autumn. As it was, the outside of the house looked bare, the jagged white stone and neat red roof almost forbidding. But inside it was different. Signs of home and family were in the fading, comfortable furniture, in the slightly scuffed tile floors and the settled air beneath high ceilings. In the living room a shaft of sunlight came through the large picture windows that overlooked the village souq where Leila could make out small figures moving in and out of the shops and along Somewhere, Home.

Leila, her sister Randa and their parents Nadia and Mahmoud were ushered to their seats by Alia, a moon-faced woman in a loose-fitting long black skirt and top with a diaphanous white veil hanging over her shoulders. Leila felt an accustomed shyness steal its way into her chest and move up into her face. She held her head down and tried to shake the feeling away.

‘Welcome to you all. Ahlan, Ahlan,’ Alia said.

They seated themselves around the room, the young women on the sofa and their parents in armchairs near the door. Alia spoke in clear, rounded tones, her white hands placed neatly on her knees as she sat on the edge of a high-backed chair. Leila shifted in her seat and stared at the older woman, unable to understand what she was saying.

‘She’s lovely-looking, isn’t she, for a woman her age?’ Randa whispered into Leila’s ear.

Since their arrival from America two months before, the young women had given up trying to understand the language their parents had grown up with and which they had neglected to pass on to them. As Alia and their parents conversed, Leila and Randa could only smile back.

It was not the first time they felt out of place in a country they had heard referred to since childhood as ‘back home’. Back home was where fragrant pine trees grew into tall umbrellas and rivers chimed down to a light-blue sea. Back home were snowy winters and balmy summers, and gentle sunshine everywhere in between. There were sandy beaches and mountains where houses perched as if on a breath of air, and people with sing-song greetings of ‘how are you’, ‘God be with you’ and ‘you have honoured our house with your presence’, at every turn.

But everywhere the little girls had looked in the green, leafy fields of West Virginia where they lived, in the small stucco house that met them on their return from school each day and the sharp, clear sound of the English they spoke with their friends was a home without memories, without a stirring, weighted past. They learned to let their minds wander whenever their parents’ conversations turned to Arabic, until the words they no longer strained to understand stumbled over one another and became one long tune that lulled them into a secret comfort.

She felt Randa nudge her and pull her up.

A tall young man with a high forehead and fine eyebrows was reaching out to shake Leila’s hand. ‘Bonjour,’ he said, smiling gently at her.

‘This is Rasheed, my son,’ Alia said with pride in her voice.

The man bent his head gracefully and when he looked up again Leila noticed a scar in the shape of a wide arch just above his left eyebrow. She saw him lift a long, smooth hand and lightly touch the scar, then he looked at Leila and smiled again. ‘Je suis désolé, mais je ne parle que le français et l’arabe,’ Rasheed said with a polite laugh. He placed a chair by Mahmoud and began talking to the older man.

Leila looked away. Since their return to the old country she had watched an unsettling joy light up her parents’ eyes every time they met relatives they had missed in their thirty-year absence, or whenever they happened upon a once familiar spot. She had felt a resistance build up within her to sharing a similar certainty in a country that she knew could never be home. Now, everything and everyone she encountered had to be approached with caution. Who would ever know? Leila asked the image in the bathroom mirror late at night when everyone who knew her had fallen asleep. Who can sense the fear in my heart? She would stare back at the large brown eyes wide in astonishment, lips mouthing a silent, round ‘O’, skin lacklustre in the faint light. The next day she would try again to erase suspicion from her memory, smiling when she could and taking delight in sudden moments of clarity, only to feel doubt creeping back into her, an insistent companion. She turned her head to look out the window once again and let sunlight dazzle her eyes until the figures around her faded into a pleasant blur.

‘Hello, there, nice to see our long-lost cousins from Virginia at last.’ The voice was abrupt, the English heavily accented. He found her hand and shook it hard.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.