Полная версия

Plant Solutions

Copyright

Published by Collins

an imprint of

HarperCollins Publishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in 2006 Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

Text © Nigel Colborn, 2006

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Nigel Colborn asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007193127

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2014 ISBN: 9780007591831

Version: 2014-08-01

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Annuals

Biennials

Bedding

Bulbs

Alpines

Perennials

Groundcover

Grasses

Ferns

Climbers

Shrubs

Trees

Water Plants

About the Publisher

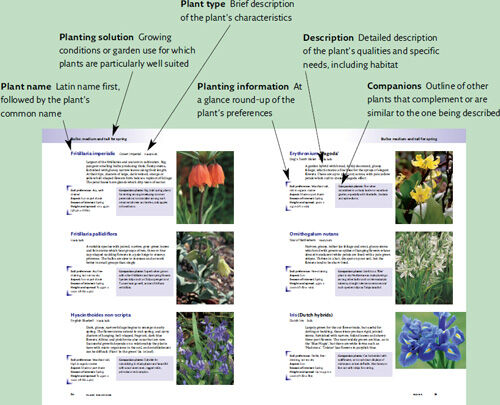

How to Use This Book

The aim of this book is to stimulate planting ideas, rather than give prescriptive formulae. Feel free, therefore, to flick through the pages at random and alight on any plants that catch your eye. The main section of the book consists of the plant directory pages, categorised as shown in the contents table, with each group – shrubs, annuals etc. – further subdivided to offer selections for specific sites. Thus, if you are searching for a medium sized shrub that prefers partial sun, you will find a choice here. Each plant entry gives essential details and a brief description, and lists suggestions for companion plants. Alternative varieties are also frequently mentioned.

Interspersed among the directory pages, you will find occasional spreads devoted to a specific plant group. Limited space allows these to represent but a tiny sample from such extensive genera as roses (ref 1 and ref 2) or clematis (ref 1 and ref 2). They are intended for use as a starting point, perhaps for a more detailed search elsewhere.

Examples of plant associations are also included, for example, here, where a scheme with annuals is described and illustrated. Like the special spreads, these are intended as prompters for further ideas, rather than as specific recipes to which one must adhere.

Although the information given is as accurate as possible, it is important to bear in mind that plants can cope with a surprisingly wide range of conditions outside their recognized ‘comfort zones’. Species which are deemed tender, can often survive low night temperatures, certain wetland plants can be surprisingly drought tolerant and plants adapted to sunny conditions may thrive in shade. Heights and dimensions can vary, too, depending on growing conditions, so be experimental, when you plant, and prepare for some surprises!

Introduction

Choosing plants can be one of the greatest pleasures of gardening, but it can also give rise to the most agonising dilemmas. The number of species and varieties in cultivation is so vast and so varied that deciding which ones to select, for a particular planting scheme, is almost impossible. And as garden sizes reduce, in an increasingly urban world, that choice becomes ever more crucial.

Every part of every garden, regardless of design or style, presents its own special planting opportunities. Whether on a grand scale, such as in a big mixed border, or in a space so confined that only tiny plants will fit, there are decisions to be made, combinations to be composed and solutions to be found. Which perennial group will blend well in this partly shaded bed? What climbers would thrive on that sheltered wall? Is there a plant that can grow in that baking hot corner or that waterlogged bog? Didn’t I even see a plant grown on nothing more than a house brick once? Every garden situation, regardless of prevailing conditions, presents a planting challenge and, for every challenge, there is a planting solution.

The purpose of this book is to serve as a launching pad for your own creative planting ideas. As many typical situations as possible have been included, with specific plant suggestions offered for each. Ample cross referencing and special sections on selected plant combinations help to develop design ideas further so that among the hundreds of individual plants mentioned in the following pages, you are bound to find inspiration to come up with the very best plant solutions for your own garden.

We assess the plants, not merely on their own merit, but as core elements of good garden design. Detailed planting recipes are not included, since these could influence or even cramp individual creativity, and cultural advice is kept to a minimum. However, once a number of potential plants has been identified for a specific site, your next step will be to develop that initial choice into a growing composition in which plants will not only thrive, but will also look beautiful together. And if such a composition works well, that beauty and interest becomes a dynamic art form which changes almost daily but sustains its constant allure, through each of the seasons.

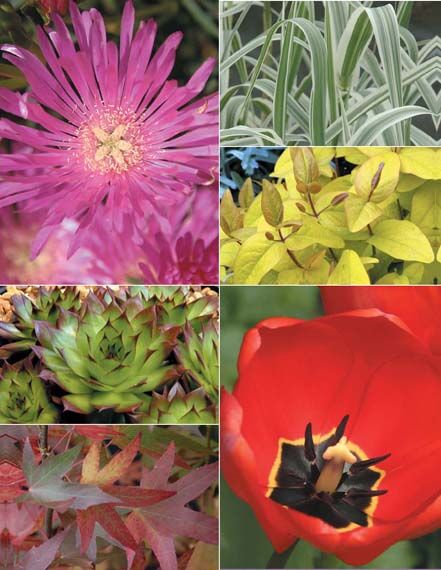

The choice of plants, for any garden situation, will be rich and varied, even if growing conditions are less than ideal.

Some Thoughts on Planting and Design

Garden design has recently experienced a stimulating revolution. In an age of growing prosperity since the mid 1990s, interest in private outdoor spaces increased sharply and by the turn of the century, gardens and gardening had entered a new era. Growth in hard landscaping burgeoned, with ever-expanding areas of paving, decking, gravel, terracing, walls and fancy fencing. Such colourful new materials as tumbled glass gravel, raw sheet copper or dyed sands were deployed, often in dramatic and mould-breaking styles. This brave new gardening world continues to develop and to evolve in all aspects of design bar one: creative planting.

Plants are a crucial element to almost all popular garden designs but their importance is often overlooked. Plant choice, even by able and experienced designers, is sometimes inappropriate, resulting in ill-composed schemes which go badly wrong, or worse, in plants that simply languish or die. Plant associations can be unsympathetic, either to the hard landscaping that surrounds them, or within the mix of chosen species. There are plant-minded designers, of course, many of whom develop original and creative planting schemes, but these are exceptions, and in the great bulk of new gardens, from major public spaces, to tiny urban oases, plants have tended to become misunderstood components.

Creative planting schemes, with varied colours, textures and sizes, help to soften the harsh effect of hard landscaping.

Creative planting is a dynamic, ongoing art form. The mixed border, below, has been boosted with temporary colour from a midseason introduction of tender, summer-flowering perennials. These could, in turn, be underplanted with spring bulbs.

Plants for bedding can be used in exactly the same way as a decorator might deploy paint or carpet – to cover a surface with a chosen colour. These African marigolds, planted after the last frost, in spring, paint a bright golden surface for the whole of the summer. While they flourish, the effect is spectacular, but when the bed is stripped away, only bare soil will remain.

Texturing Plants

Given a sound structure, usually provided from a combination of hard materials and woody plants, the bulk of any planting scheme is likely to be concerned with filling the spaces in between. The term ‘in-fill’ or ‘space filling’ suggests that these plants are less important than the structure but the opposite is true. The soft planting, in all its guises and styles, plays the most important role of all. These are the plants that create the desired mood. They will often be the most rapidly changing, and so will deliver the essential dynamic of a well-tempered garden. Since, by volume, texturing plants usually make up the largest area, they will have the most influence on colour schemes, on texture, on planting styles and on ensuring sustained interest.

By policing in-fill plants, one can develop changes of mood and style from one part of the garden to another, or from one season to another. Bursts of special interest can be engineered to take place in specific garden spots, by concentrating in-fill plants that will synchronise their performance with their neighbours. A woodland garden, for example, may be a cool, shady, green retreat from the heat of summer where little is in flower and berries have yet to ripen, but in winter and spring, the same area could host a mass of highly coloured bulbs and perennials from snowdrops, hellebores and yellow winter aconites in mid-winter to wild narcissus, epimediums, primulas, and fritillaries in mid-spring. A dry garden, developed for minimal water use, will benefit from being well furnished with evergreens – especially those with distinctive foliage – so that the seasons are linked by a constant background, and so that there is something beautiful to look at during extreme summer heat or in the depths of winter.

When plants are teamed, colours in one variety can pick up sympathetic tones in the hues of its neighbours. Here, the bell flowers of the tall Campanula echo the mauve and pink hues of the annual candytuft.

Planting for the Senses

Although it seems pretty obvious, it may be worth remembering that good planting will stimulate more than just the eyes and nose. In a richly planted garden, there will be plants to listen to and to touch, as well as those that look pretty. This dimension becomes doubly important if a planting scheme is designed for people who lack one or more of the five senses.

Sight The most obvious of the senses, for gardeners, but there are subtleties frequently overlooked. Pale pastel colours and whites, for example, are best for planting schemes which may be viewed mainly in poor light or at night. Very dark colours tend to vanish into shadow, when viewed from a distance, whereas pale ones stand out. In bright light, pale colours appear washed out, whereas strong hues become more arresting. Large flowers, in strong colours, have far more influence in the overview of a border or plant group than do lots of small flowers in even much brighter colours.

Fragrance The second most important of the senses, in a garden, is the sense of smell. Plants with a desirable fragrance are best placed where they are readily accessible to the nose; those which have an unpleasant odour should never be placed where they can spoil the garden experience, but may still be worth growing for other reasons. When blending fragrances, some go better together than others. The richness of summer jasmine, for example is expanded to Wagnerian sensuality if teamed with the perfume of honeysuckle and Nicotiana affinis. The smell of lavender adds a firmer dimension to the sweeter perfume of old roses.

Touch So many plants are pleasant to stroke, or to feel. Many of the artemisias, for instance, have silky textured filigree leaves and are aromatic as well. The shining, bright tan trunk of the Chinese cherry species Prunus serrula makes it worth growing, just to look at, but extra pleasure comes from being able to caress that smooth, polished bark.

Taste Taste is less critical, but if you want to grow a hazel nut for its beautiful foliage, or edge a border with wild strawberries for their decorative value, being able to eat the produce provides an added bonus.

Sound Sound can help to create special moods. A breeze blowing through aspen leaves makes a noise identical to falling rain; wind in a pine tree sighs and sobs whereas winter gales make the tall dead stems of Miscanthus grass hiss in a disturbing manner. Classical Chinese gardeners were said to have had the tradition of planting large, broad leaved specimens just below the eaves of a building, and close to a window, so that during rain, the sound of water drops striking them would be audible from within. The effect, apparently, was to enhance the melancholy mood of a wet day.

The long, curving leaves of Bowles golden sedge, Carex elata ‘Aurea’ (left), harmonise with the yellow-leaved form of meadowsweet, Filipendua ulmaria ‘Aurea’, while their textures make a dramatic contrast.

The best plants make multiple contributions. The pink, variegated petals are the obvious asset of this old gallica rose, ‘Rosa Mundi’, but it also provides sweet fragrance and makes a sumptuous texture contrast with the yellow-green lady’s mantle growing nearby.

Planting for the Emotions

Less obvious than planting for the physical senses, carefully devised planting will also stimulate an emotive response. A feeling of calm, for example, is enhanced when gentle colours and subtly blended foliage textures are deployed. But when colours are strident and there are strong colour contrasts, the viewer tends to feel more agitated, particularly when plants with spiky outlines are used, or where trees have irregular limbs. Examples abound, of how specific planting schemes stimulate particular emotions. Here is a small selection, presented in opposing pairs:

Hot/cool; calm/agitated As a general rule, cool colours – blue, white, green – are calming, whereas hot oranges, reds and golds can be agitating. But blues are cold and can lack passion whereas bold, burning reds stir the blood and hot oranges actually make one feel warmer.

Low-key/high key In some parts of a garden, planting is best if low-key. Uniform ground cover – or a lawn for that matter – makes a gentle foil, allowing neighbouring features, whether plants or objects, to stand out. A frequent mistake made by people who remove their lawns is to install a gravel surface, but then to plant it so busily that it becomes a strong feature in its own right, perhaps overshadowing surrounding borders or planting schemes. Where a strong, bold statement is needed, however, planting must rise to the need, drawing one’s eye and dominating the scene. A single main architectural plant, or a small group, may suffice, but a canny plant designer will keep an eye on such a group and keep finding ways to make its impact even stronger.

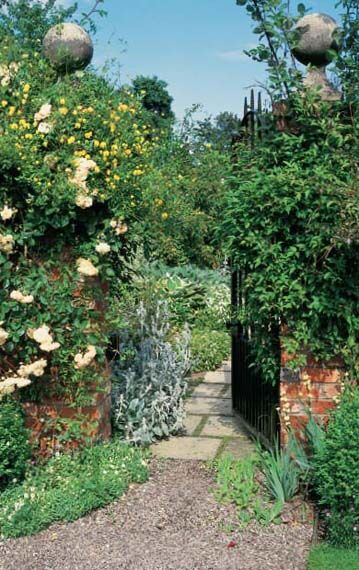

Inviting/forbidding Careful placing of plants, particularly near entrances or where different sections of a garden are divided, are able either to make a welcoming pitch, or to discourage entry. Both techniques are valuable. Where the entrance is narrow – through a gateway, perhaps, or under an arch, a carefully placed plant with interesting foliage colour or conspicuous blossoms will help to draw people in. If the arches or gateways are themselves well furnished with handsome climbing plants, perhaps with special treasures also grown at their feet, a visitor might pause there, to enjoy the moment, before passing through.

A sea of spring daffodils induces a feeling of calm and well-being thanks to the delicate contrast between the soft, pastel colour of the flowers and the subtle greens of the stems and foliage.

Where there needs to be private access, whose use is to be limited, the opposite of these measures can be taken. Shrubs can be allowed to expand and disguise the thoroughfare, or planting in front can be staggered so that only those ‘in the know’ are inclined to slip through. And in places where security is a concern, ostentatiously thorny, dense vegetation can do a lot to back up the threat of any spiked railings or fencing which stands between it and the outside world.

Intellectual versus emotional This is a more difficult concept to believe in, but with planting, just as in an instrumental concerto, there is often a tension between two forms. With the musical analogy, the solo instrument converses with the orchestra, sometimes in unison, but mostly in a melodious dialogue. In a garden, formal landscaping – whether with plants or structures – can have a similar dialogue with more naturalistic planting. Formal geometric shapes are the result of an intellectual exercise, Man imposing himself on Nature. Line and form have been carefully considered and structures – be they plants or man-made objects – are laid out in strictly disciplined patterns. Eighteenth century parterres, Victorian bedding schemes and some modern day public plantings are examples of these. Wild, natural landscapes are the antithesis of this cerebral approach. Topography and vegetation are seen as nature intended and the rules of symmetry appear to be broken. Naturalistic designs in gardens take the main elements of beauty from truly wild landscapes and compose them to create romanticised scenes. Streams or ponds appear like natural water courses and planting is in layers – trees, shrubs, understorey – more or less as you would find in rural regions.

In most gardens, however, both concepts are adopted and there is a stimulating tension between the two. An artificial flower meadow, for example, might be skirted – as in the author’s garden – by fine-mown lawn, and a clipped shrub screen. In many modern versions of Elizabethan knot gardens, summer perennials are allowed to progress and flower fairly freely, whereas the originals would have been much more formally planted.

A gateway that is well furnished with interesting plants and flowers will be more inviting than bare pillars and a gate. If this many plants decorate the entrance, how much more will there be to enjoy inside?

Floral fireworks! The seed heads of Allium schubertii bring a touch of drama to this dense, mixed Mediterranean planting scheme.

Planting in Specific Styles

Planting styles will depend very much on overall design, and on personal preference, but it is worth considering some of the most popular and distinctive of these:

Classic mixed borders

Mixed borders must be large enough to accommodate shrubs – perhaps even trees – along with herbaceous perennials of all sizes, probably interspersed with annuals or biennials for gap-filling and even a succession of bulbs. These are the most malleable and, over time, will run through gentle but profound changes. Colour can be carefully controlled, with main themes, such as red, white, hot or cool hues, or may roll through a series of intriguing changes with the season.

It is important to view such borders at all levels, and to bear in mind how they are likely to look in all seasons. Whenever any major changes are made to the planting, this is likely to have a ‘knock on’ effect on other times of year, so that one big change necessitates further changes down the line. These are ongoing, long-term planting schemes which can be adjusted and tinkered with over decades, and which will keep most keen gardeners both occupied and pre-occupied for a very long period. It is said that the Edwardian garden guru, Gertrude Jekyll, spent over forty years adjusting the borders at her garden, Munstead Wood.

Cottage-style planting works well beneath the walls of a 300 year-old building. The climbing Bourbon rose, ‘Kathleen Harrop’ furnishes the limestone, without hiding too much of it, and teams with the colour of the pink valerian which is allowed to seed around freely.

Mediterranean

With water becoming a scarce commodity and, in some areas, an expensive one, much attention is being turned to low-water planting schemes. Typical natural landscapes, whose arid beauty is well worth imitating, occur in such places as the rocky Mediterranean coastal regions, the southern tip of Africa, the American Chaparral and in many parts of Australasia. Such areas have amazingly rich floras and many of their native plants have become garden staples. Gladiolus, Lavandula and Eschscholzia are examples of the thousands of widespread plants which enjoy similar conditions.