Полная версия

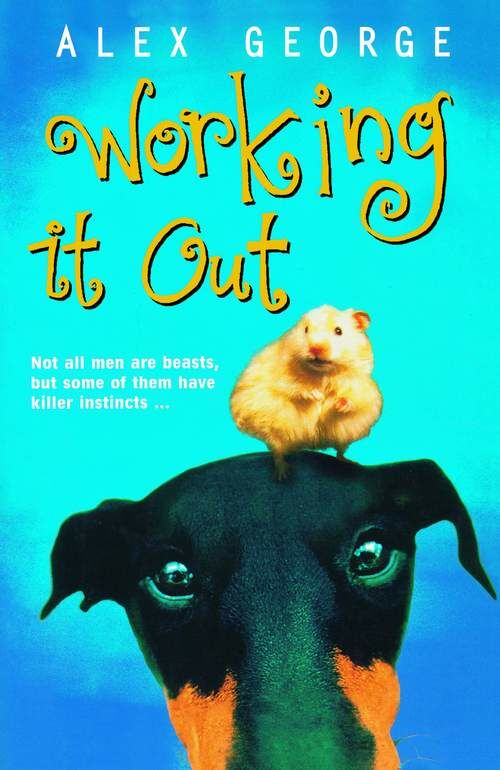

Working It Out

Working It Out

Alex George

For Christina

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

ONE

Johnathan Burlip zipped up and sighed. There was something reassuring about peeing in Chloe’s bathroom. Watching the blue, Domestos-drenched water in the bowl ripple and then assume the hue of the flesh of a ripe avocado, he had reflected that some things in life never changed, immutable in their truth and simplicity. Two and two still made four, and when you mixed blue and yellow, you still got green. Such things were precious, to be grasped in times of crisis.

He looked around the terracotta and black bathroom with distaste as he pulled the duck that sat suspended in mid-flight on the end of the flushing-chain. Blue noisily replaced green, ready for the process to be repeated. Johnathan sat down on the loo he had just used, and wondered what to do. He desperately didn’t want to go back downstairs. He traced a line through the brown Terylene shagpile with his foot, and considered possible excuses. An upset stomach, perhaps. Chloe’s aggressive vegetarian dietary tactics always had an adverse effect on his digestive system. Results were spectacular, having a similar effect on the lavatorial plumbing to that of a jack-knifed lorry in the Dartford Tunnel on a Friday night. Nothing got through. No U-turn. No U-bend, for that matter.

Johnathan decided that nobody would be convinced. He belched chickpea and got up. He opened the door and slouched towards the stairs, stopping outside the kitchen to consider a petunia, which he had given Chloe some months previously by way of apology for some deemed transgression, he forgot what. The plant looked how he felt. Thirsty. And wilting.

The door opened and Chloe’s sister Harriet appeared. She looked at Johnathan balefully. Her eyes were smudged with cheek-bound mascara.

‘How is she?’ he asked.

Harriet considered. ‘Like Eeyore with a period.’

‘Oh dear,’ said Johnathan.

He went into the kitchen. Chloe was slumped in a chair at the large table in the middle of the room, staring into a half-empty wine glass. She did not look up as he approached.

‘Um,’ said Johnathan.

Chloe did not move.

Johnathan waited, wondering what to do. He glanced over towards the sink. Troilus was lying on the floor, horribly inanimate. The pool of blood which surrounded his squashed head like a halo had started to expand with a ghoulish inevitability towards the fridge.

‘I’ll get a cloth,’ he said. He went to the cleaning cupboard and began to pad kitchen roll around the edges of the growing puddle.

Once the tide of blood had been stemmed and the sodden roll disposed of, Johnathan stood up and waited for instructions. Her eyes still fixed firmly on her wine glass, Chloe finally said, ‘Bury him by the mange-touts, and then leave. Don’t come back.’

‘Right,’ said Johnathan, wondering what decomposing cat did for the nutritional qualities of vegetables. He rolled up his sleeves and picked up the dead animal, who responded with a last spirited gush of cloying blood, scoring a direct hit on Johnathan’s trousers. Johnathan smiled grimly. He didn’t care. Got you at last, you little bastard. He went outside to look for a spade.

Johnathan Burlip detested cats. He was very, very allergic to them. If there was a cat within two hundred yards, it would unerringly track him down and snuggle up to him, purring in unreciprocated affection. He had about ten seconds in which to whip out a handkerchief with which to stem the ensuing nasal catastrophe.

Troilus, unfortunately for him, had been particularly fond of Johnathan. He loved to coat Johnathan with his fur, huge quantities of which seemed to disengage automatically on contact. Johnathan’s enmity towards cats in general developed a new focus of Troilus in particular. Over time, this had gradually developed into an unhealthy paranoia. He used to have nightmares in which Troilus could speak, dance and sing. One night he appeared as Mephistopheles and explained how Macavity wasn’t that much of a mystery cat, he just had a good agent.

Johnathan kicked Troilus into the hole he had hurriedly dug. The chapatti pan had scored a direct hit on Troilus’s cranium, causing instant departure for Cat Heaven. Johnathan had been drying the chapatti pan after dinner, while Troilus, as usual, had been sitting archly at his feet, particles of cat wafting from his fur up Johnathan’s nostrils. Just as the chapatti pan was dry, the urge to wallop Troilus became overwhelming. Johnathan hadn’t really thought through the consequences. He was suddenly overcome by tiredness and irritation, and after a brief internal dialogue, the essence of which was ah, fuck it, he had deftly played a forceful on-drive with uncharacteristic accuracy and panache, Troilus’s head obligingly playing the part of the cricket ball. Wop. Out.

Johnathan covered the dead body with topsoil and enjoyed a brief jig of victory on his victim’s grave to smooth out the surface. He trudged back towards the warm lights of the house. Chloe had vanished from the kitchen. Instead Harriet had returned downstairs and sat at the table, watching the steam rise on the last cup of decaf of the day.

She looked at him. ‘She’s gone to bed,’ she said.

‘Right,’ said Johnathan awkwardly.

There was a pause.

‘Prat,’ remarked Harriet.

Johnathan shrugged. ‘I’ll let myself out,’ he said.

‘Bye,’ said Harriet.

Johnathan nodded, and opened the front door.

On the cold Fulham street a few empty crisp packets tangoed listlessly between the parked Peugeot 205s. He turned up the collar on his coat and headed down the hill towards Parsons Green tube.

TWO

The telephone was ringing.

Slowly, very, very slowly, its insistent shrilling filtered through the syrupy mire of Johnathan Burlip’s sleeping brain. As consciousness arrived, he became aware not only of the telephone but also of a brutish throbbing just behind his eyes. He groaned, rolled inelegantly out of his bed, and tottered out of the bedroom. Barely awake, he picked up the phone and said,

‘Ugh.’

There was a pause. Then:

‘Bastard.’

Johnathan blinked. He swayed slightly. The throbbing was spreading from his eyes backwards into his brain and upwards to his temples, where it sat, deeply malignant, radiating pain. The clock in the hall seemed to suggest that it was six o’clock in the morning. He waited.

‘Bastardbastardbastard.’

Johnathan closed his eyes. It was Chloe.

‘Hello Chloe,’ he said.

‘Oh no you don’t. Oh no you bloody don’t. Don’t think for one minute that you’re going to sweet-talk your way out of this one. No way. Not this time. End of story. You’re history.’

‘OK,’ said Johnathan.

‘Look,’ said Chloe, ‘don’t even bother trying. It’s a waste of time. It won’t work. It’s pitiful, actually. You’re pathetic. You’re just a drivelly, snivelling pathetic man. God. I can’t believe this. At least have a bit of dignity.’

‘OK,’ said Johnathan.

‘I mean, Jesus. You killed my cat. You’re a murderer. I should report you to the police. The RSPCA. You are in serious trouble. Serious. You can just forget everything. How you can even ask me to contemplate having you back at this stage is beyond me.’

Johnathan woke up. He had asked no such thing, and nor was he going to. Best to make that clear right away. ‘You’re right,’ he said quickly. ‘I killed your cat. I killed Troilus. I am a murderer. I am vermin. You wouldn’t want to see me again even if I was the last person on the planet.’

Chloe’s tone softened. ‘This self-hate is not good for you,’ she said. ‘You’ve always had low self-esteem. It’s not going to get you anywhere. You need to look at yourself in a more positive light. You do have some good qualities.’

Johnathan started to hop up and down in agitation. This was not going according to plan. ‘I killed Troilus,’ he reminded her.

Chloe sighed. ‘I know. I don’t pretend to understand why. You were looking for a form of externalizing your emotions, you wanted to project your frustrations. You were caught up in the sub-luminous ego strata.’

Johnathan frowned. ‘What?’ he said.

‘But you have a problem. You’re angry about something. You should try and talk about it. You need professional help. It’s nothing to be ashamed of. I go all the time. It’s been enormously uplifting, just to be able to share my problems with a sympathetic ear. Voicing my hopes and fears out loud helps them to crystallize within me. I come out more fulfilled, more rounded. More me.’

More fucking nutty, thought Johnathan blackly.

‘Chloe,’ he said after a few moments. ‘It’s over, isn’t it?’

‘God, don’t say that. Don’t ever say that. It’s never over. Things are never that bad. Christ. Things are worse than I thought. You must snap out of it, Johnathan. Come back from the edge. Take a step back and see the better you.’ Chloe’s reedy voice rose a few pitches with excitement.

Johnathan sighed. ‘No, not that. Us. You and me. We’re over. Finished. Aren’t we?’

‘Oh,’ said Chloe, the disappointment audible. ‘I see.’

‘I mean,’ said Johnathan reasonably, ‘I did kill your cat.’

Chloe thought about this. ‘We all have our moments of madness. The insuperable super-ego plays its trump card.’

‘But surely you must hate me now,’ said Johnathan hopefully.

‘Hate? What is hate, at the end of the day?’

‘Listen,’ said Johnathan quickly, keen not to get side-tracked. ‘You’re obviously still very upset. I understand that. You need some time alone. I’m sorry to have caused you so much grief. I understand if you’ll never want to see me again,’ he said.

‘Sweetie,’ cooed Chloe. ‘You’re being terribly hard on yourself–’

‘But I must, I must,’ cried Johnathan, and slammed the receiver down. He stood still for a few moments, dazed, wobbling slightly with queasiness and sleep. His mouth felt as if a herd of camels had surreptitiously crapped in it during the night.

He went into the kitchen and opened the fridge door, squinting against the anaemic glow of the electric fridge light, which felt as if it was burning holes in his retinas. There was no bottled water left. Of course there wasn’t: he had drunk it all when he had arrived home last night, hoping to stave off the mother of all hangovers. The empty bottle lay on its side near the bin. Johnathan dispiritedly took a glass and filled it with warm, slightly opaque liquid from the tap.

Chloe was addicted to self-help manuals. She could speak meaningless psycho-babble fluently, in several different dialects. She could analyse your dreams, tell you how to give up smoking or lose weight by meditation, determine what was the right job for you, and offer potted highlights of all of the world’s leading religions. Johnathan had had enough of her hectoring, if well-meaning, didacticism. All he wanted was to be left alone. It was extremely trying to have one’s numerous weaknesses pointed out and dissected at every available opportunity.

One of these weaknesses, it transpired, was spinelessness. Johnathan had decided some months ago that he could not take any more of Chloe’s banalities, but since then had done nothing until his contretemps with Troilus the previous evening. With anyone other than Chloe the best way to end matters would have been to explain gently that it was time to move on, sorry, and there are plenty more fish in the sea, and it’s not you, it’s me, and I just don’t deserve you, and so on. Johnathan realized that this approach would not work with Chloe: she would somehow manage to twist his words back on themselves and he would in all probability find himself engaged. Instead he had attempted a more oblique approach. In the lowest, slyest way possible, he did everything he could to make life for Chloe so unbearable that she would feel obliged to dump him.

One of the difficulties with this, however, was that he would find himself blinking in disbelief at Chloe’s equanimity as she calmly accepted his most outrageous and offensive behaviour with a brief shrug. Chloe clung on to the relationship with the tenacity of a pit-bull terrier. An entire section of her library was dedicated to Resolving Your Differences, Making that Love Work for You!, Talking it Through, and so on. Johnathan realized that there was a long, long way to go before she had exhausted the remedies available on her bookshelf.

Chloe’s refusal to accept the obvious was the principal reason for Troilus’s fate the previous evening. It had been in many respects a political execution, Troilus no more than a hapless pawn in an altogether more complex game. Johnathan had finally had enough. He had never knowingly killed anything before, apart from the odd mosquito or bath-trapped spider, but couldn’t find it in him to feel much remorse. Troilus was only a cat, after all.

Johnathan went back to the bedroom and retreated under the duvet. Eventually he drifted off into a restless sleep, merciful respite from his aching head. He had not been asleep for long, though, when the telephone erupted once more. Cursing, he walked out into the hall.

Johnathan regarded the telephone suspiciously. He looked at his watch. It was now eight-thirty. It had to be Chloe. The ringing seemed to be getting louder. It felt as if someone was jabbing a needle into his ear. Finally he picked up the receiver, bracing himself.

‘OK you crazy bitch,’ he said. ‘I’m ready.’

There was a discreet cough. ‘Hello darling.’

His mother.

‘Oh. Hi,’ he mumbled. ‘Thought you were someone else.’

‘We’re just off out of the door for this festival in Cardiff, so I thought I’d give you a ring.’

‘Right.’

‘So how are you?’ asked his mother breezily.

‘Fine.’

There was a slight pause. ‘You sound a bit put out, darling. Are you sure you’re all right?’

‘I’m fine.’

‘I didn’t wake you up, did I?’

‘Well, yes, actually, you did,’ said Johnathan as equably as he could.

‘But it’s such a beautiful day,’ said his mother. ‘How can you bear to spend it all in bed?’

‘I wasn’t going to spend it all in bed. I was just having a well-deserved lie in,’ replied Johnathan, aware of the disapproval emanating silently down the line but too hungover to care.

‘And what,’ continued his mother, ‘are you up to this weekend?’

‘All the usual chores,’ said Johnathan. ‘Washing, ironing, that sort of thing. You know me. Glamour glamour glamour.’

‘Oh. If you didn’t have anything special planned you could have come with us. Too late now, though.’

‘Oh well,’ said Johnathan, brightening slightly.

‘It should be absolutely fascinating,’ continued his mother. ‘They’re putting on a lesbian Macbeth, in Welsh.’

‘I see,’ said Johnathan. There was a long pause.

‘Anyway, darling, we must dash if we’re going to miss the traffic. I’ll give you a call early next week. Bye.’

‘Bye.’

Johnathan thought about his parents on their way to their latest jaunt in Wales. To them, culture was a commodity which could be acquired and traded. His parents patronized (in both senses of the word) a stable of unknown artists, whose works hung throughout their cluttered North London home. They invested speculatively but without aesthetic discrimination in the hope that one day the painters would become hugely important and their paintings hugely valuable. Some of the paintings were all right, others were capable of inducing powerful migraines. One looked like an ink-blot test given to deranged children from dysfunctional families. Others looked as if they’d been painted by the children who did the ink-blot tests.

Johnathan’s parents firmly believed that there was a direct correlation between culture and society: the higher the culture, the higher the society. Put another way, the more impenetrable the culture, the more impenetrable the posh accents. They liked to surround themselves with creative people. They knew artists, musicians and writers of varying pedigree, members of the Hampstead authordoxy. They knew a lot of women called Hermione. They were so highbrow their foreheads were permanently stuck to the ceiling.

Johnathan, however, was a solicitor, and was therefore a considerable disappointment to his parents. It was not something they could drop into conversation with any hope of carving further notches on the bedpost of artistic pretension. ‘My son the solicitor,’ didn’t have quite the same ring about it as ‘My son the bleak playwright’, or ‘My son the post-modern poet’.

Johnathan, though, suspected that he had an even greater failing in his parents’ eyes. He was straight. He liked girls. He was incontrovertibly heterosexual.

There wasn’t anything specific he could put his finger on to justify his suspicion, but the cumulative circumstantial evidence seemed compelling. He had been encouraged with his dried flower collection from an early age. For his fourteenth birthday he had received a copy of Joe Orton’s diaries, and was earnestly told that it represented a viable lifestyle choice. His parents always looked rather crestfallen when he introduced them to new girlfriends. Worst of all, though, they had added an ‘h’ to his name.

Johnathan’s extra ‘h’ had been a source of irritation and inconvenience for as long as he could remember. Nobody except for his parents knew quite why it was there, squatting like an uninvited guest in the middle of his first name. Every credit card, chequebook, and bill missed out his ‘h’. The only people who ever spelled his name correctly were the promotions department at Readers’ Digest who regularly tried to entice him into entering the Biggest Prize Draw Ever. He had grown accustomed to watching people frown slightly as they looked at his business card, while they tried to work out what was wrong with it. Johnathan had become convinced that his parents had burdened him with the redundant consonant to show that their son was somehow different. Well, maybe he was, but not that different.

Sexually Johnathan had grown up in a drearily unspectacular way. He finally managed to lose the millstone of virginity during his first, parent-free, week at university in the traditionally messy and awkward way. He was leerily propositioned by an unattractive and very drunk biochemistry postgraduate in the college bar, and woke in her bed the next morning experiencing elation, disgust, and a splitting headache. After that Johnathan had failed to have proper sex with anyone else until he had left university.

Johnathan remembered that there was a bottle of aspirin in the bathroom. His hangover was clearly too sophisticated to be dealt with simply by way of sleep. Something chemical was required. He sloped off to the bathroom, took three pills, and went into the kitchen.

Johnathan switched on his espresso machine, which soon began to chugger and whoosh and gurgle in a way more soothing than any mother’s heartbeat. He had never really stopped to consider his relationship with his coffee machine from a Freudian perspective. It was certainly closer than the one he enjoyed with his mother.

When the little yellow light on the machine clicked itself off, Johnathan flicked the switch and watched as the twin nozzles which hung beneath the matt black belly of the machine began to trickle thick, black liquid into the waiting cup. A few seconds later, the cup was full. Johnathan lifted it to his nose and breathed in deeply, relishing the espresso’s aroma. He sighed a small sigh, and then tipped the contents of the cup down his throat in two quick movements, rather as if he was taking medicine. Johnathan shut his eyes for a few moments, and allowed his mind to go blank. Then he opened them again, and switched the coffee machine back on. Round two.

Some hours later, fully caffeined-up and a few chores to the good, Johnathan sat on his sofa watching a children’s Saturday morning television show. His hangover had slowly cranked itself up to full throttle at around ten o’clock but since then had been winding down so that now it only hurt when he moved or thought. Watching children’s television required him to do neither.

Johnathan’s dog, Schroedinger, was asleep next to him on the sofa, his head resting peacefully in Johnathan’s lap. Nobody knew exactly what unlikely communion had produced him. He looked like the result of a bizarre experiment where a Scottie had mated with a porcupine.

When first-time visitors to the flat met Schroedinger, the conversation always followed the same course with an inevitability which Johnathan had begun to resent.

Visitor: Ah, what’s his name.

Johnathan (gloomily, for he knows what is to come): Schroedinger.

Visitor (frowning): You can’t call a dog Schroedinger.

Johnathan: Why not?

Visitor: Well, you know, Schroedinger’s Cat.

Johnathan (peevishly): Yes?

Visitor: So. It would be all right for a cat, but not for a dog.

Johnathan (testily): But the cat wasn’t called Schroedinger. The cat belonged to Schroedinger. Sort of.

Visitor: Yes?

Johnathan: So, logically, a cat is the last creature you would call Schroedinger.

Visitor (uncertainly): Because.

Johnathan: Because cats don’t own cats.

Visitor: Are you telling me that your dog owns a cat?

Johnathan: No of course not–

Visitor: Well then.

Johnathan:–all I’m saying is that, logically, it makes more sense to call a dog Schroedinger than a cat.

Visitor (unconvinced): But Schroedinger’s Cat.

Johnathan: OK, take another example. Take a Rubik’s cube.

Visitor (unsure where this is leading): OK.

Johnathan: Well, you obviously wouldn’t call a Rubik’s cube ‘Rubik’, would you, because we all know that’s the name of the chap who invented it.

Visitor: ?

Johnathan: Look, if you’re going to be picky, Schroedinger’s Cat was dead anyway.

Visitor (cleverly): Ah, but that’s the point. We don’t know that.

It was on days like this that Johnathan was relieved that Schroedinger was, if anything, lazier than he was. He was not the sort of dog which insists on dragging its owner for a brisk tour around all the interesting piles of dog shit in the area within five minutes of its owner’s first bleary-eyed appearance in the morning, and Johnathan loved him dearly for it. Schroedinger preferred to remain in the relative tranquillity of Johnathan’s small garden, where he could relax and defecate at leisure.

Johnathan sat back and sighed. He stared up at the ceiling and considered the weekend that lay ahead. His fridge was presently home to a half-empty jar of mayonnaise and an onion. His entire week’s washing lay crumpled at the foot of his bed.