Полная версия

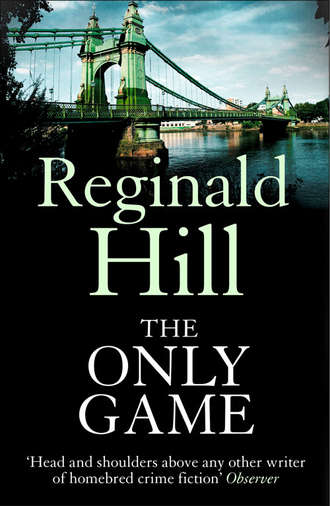

The Only Game

A priest came down the aisle. Sensing her uncertainty, he asked courteously, ‘Can I be of any assistance?’ He was an old man with a kind face but his accent was straight out of O’Connell Street.

‘No, thank you,’ she said harshly, and turned on her heel and left.

Flight or victory? Would any other accent have had her on her knees?

Then she had seen Cicero and for one superstitious moment felt that perhaps God was laying her options unambiguously in view.

Now she watched his car out of sight before hurrying down the side of the church, following a gravel path that continued between mossy headstones till it reached a graffiti’d lych-gate which opened onto a quiet side street.

Here she paused, sheltering from the rain under the gate’s small roof, and summoning reason back to control. Where should she go? Not her flat. Cicero had told her he’d got someone waiting there. Run home to mother? That’s what she’d done last time, with mixed results. But she couldn’t do it this time, not with the news she would have to bear. Besides, Cicero of the unblinking brown eyes would soon ferret her mam out.

No, there was only one place to go, one person to turn to. No matter if angry words lay between them. There and only there lay her hope of welcoming arms, of a sympathetic hearing, of lasting refuge.

Putting her head down against the pelting rain, she began to walk swiftly towards the town centre.

6

Dog Cicero parked his car obliquely across two spaces and ran up the steps into the station. A small man wearing oily overalls and a ragged moustache blocked his way.

‘Call that parking?’ he said. ‘You’re not in bloody Napoli now, Dog.’

‘I hate a racist Yid,’ said Dog. ‘You done that car yet, Marty?’

‘Report’s on your desk.’

‘What’s it say?’

‘Given up the adult literacy course, have we? All right, car’s a rust bucket but not a death trap. Should scrape through its MOT.’

‘How’s the engine? Poor starter?’

‘No. Fine. In fact in very good nick, considering. It’s the upholstery, not the mechanics, should be interesting you, though.’

‘Why’s that, Marty?’

‘Some nice stains on the back seat round the kiddie’s chair. That black poof from the lab’s looking at them now. Hey, doesn’t anyone say thank you any more?’

‘I’ll give you a ring next time I feel grateful,’ Dog called over his shoulder.

As he ran up the stairs to his office a youngish man in a shantung shirt and dangerously tight jeans intercepted him.

‘You’ve got a visitor,’ he said.

‘No time for visitors, Charley. Can you raise me Johnson at Maguire’s flat?’

‘No-can-do,’ said Detective Sergeant Charley Lunn, with a built-in cheerfulness some found irritating. ‘There’s no phone there and it’s a radio dead area. Shall I send someone round?’

Dog thought, then said, ‘No, I’ll go myself. You get anything for me on Maguire, Charley?’

He’d instructed his sergeant to run the usual checks, not with much hope.

But Lunn said, ‘As a matter of fact, I did. Maguire’s her real name, by the way, not her married name …’

‘I know that,’ said Dog impatiently, leading the way into his office.

‘… and she’s twenty-seven years old, born Londonderry, Northern Ireland, but brought up since she was nine in Northampton where her widowed mother still lives …’

‘You got an address?’

‘Surely. Here it is. To continue, our Maguire trained as a teacher at the South Essex College of Physical Education, qualified, and got a job at a Sheffield secondary school, but quit in her probationary year …’

‘Is any of this relevant?’ interrupted Dog. ‘And where the hell did you dig it up anyway?’

‘Obvious place,’ said Lunn modestly. ‘I punched her into the central computer and out it all came.’

‘Good God. What’s she doing in there? Has she got some kind of record?’

‘Indirectly. It’s a bit odd really. Seems that during this teaching year, she went with a school party on a walking tour up on Ingleborough in Yorkshire. There was some kind of row which ended with her hitting a girl who took off into the mist and fell down a pothole. The place is honeycombed with them, I gather. The girl was seriously injured and the family tried to bring a private prosecution against Maguire for assault but it never got off the ground.’

‘Then why the hell is it on the computer? And what did she do after she resigned from teaching?’

‘Don’t know. That was it. Any use?’

‘The address might be,’ said Dog. ‘Charley, get a general call out for Maguire, will you? Nothing heavy. Just to bring her in for her own good.’

‘It shall be done. You won’t forget your visitor, will you?’

‘I’ll do my best. Who the hell is it anyway?’

‘Not just any old visitor,’ grinned Lunn. ‘A real VIP. Very Indignant Person. It’s Councillor Jacobs. He’s making do with the super till you get back.’

‘They were made for each other,’ grunted Dog. ‘He can wait a bit longer.’

As Lunn left, he picked up the phone and dialled.

‘Dog, my man! Knew it was you. Recognize that ring anywhere, as the actor said to the bishop. It’s the stains in the car, right?’

‘Right. Got anything yet?’

‘Natch. Can’t hang around when it’s a job for Generalissimo Cicero, can we? It’s blood and it’s Group B. How does that grab you?’

He looked at the copy of Oliver Maguire’s record he had taken from the kindergarten. Blood Group B.

‘Where it hurts,’ he said and replaced the receiver. The phone rang instantly.

‘Dog, could you pop along to see me? I’ve got Councillor Jacobs here and he’s keen to meet you.’

Detective Superintendent Eddie Parslow had been a high flier till his late thirties when the heat of a peptic ulcer had melted his wings. Since his return to work, his sole aim had been to achieve maximum pension with minimum stress. A foxy face and lips permanently flecked with the white froth of antacid tablets gave him the look of a rabid dog, but none need fear his bite who did not disturb the even tenor of his ways.

Jacobs was a stout, florid man who needed no padding when he played Father Christmas at the council’s children-in-care party. He was clearly not in a ho-ho-ho-ing mood.

‘I gather this Maguire woman’s been stirring things up,’ he growled. ‘I thought I’d make sure you’d got the record straight.’

Dog glanced at Parslow and received a little shake of the head. He took this to mean that nothing had been said to the councillor about the real reason for their interest in Maguire.

‘That’s what we like,’ he said equably. ‘Straight records. So what happened, Councillor?’

‘She was massaging my back,’ said Jacobs. ‘When I turned over, she pulled my towel off and said, “Fancy a bit of relief? It’ll only cost a pony.”’

‘And what did you take this to mean?’

‘I took it to mean she was offering to masturbate me for twenty-five pounds,’ said Jacobs sharply. ‘What the hell else could it mean?’

‘Hard to say,’ said Dog. ‘Were you erect, by the way?’

‘What?’

‘Erect. Excited. It’d be natural. Pretty girl rubbing your body …’

‘No, I was not erect,’ snarled Jacobs. ‘What the hell is this? I have a massage at least once a week. I don’t care if it’s a pretty girl or Granger himself, as long as it helps my back. God, I knew I should have had her arrested straight off and not given her the chance to pour her poison out …’

‘Why didn’t you?’ asked Dog. ‘Call us straightaway, I mean. A man in your position with your reputation can’t be too careful.’

‘Don’t you think I know it? Mud sticks. I thought, better to forget it perhaps. Also George Granger’s by way of being a friend. I didn’t want to get his centre into the papers.’

‘Very commendable,’ said Dog. ‘So you decided very altruistically to keep stumm, till your mate Granger rang you up to say I’d been round?’

‘I don’t like your tone of voice,’ said Jacobs softly. ‘As it happens I didn’t keep stumm. As it happens I was chairing a meeting of the Liaison Committee this afternoon and Jim Tredmill, your Chief Constable, was there, and after the meeting I had a word with him, asked his advice. He said I’d probably done the right thing, no witnesses, hard to prove, but he’d see his men kept their eyes open for this tart. Clearly he hasn’t had time to ask you yet, Inspector. But never fear. I’ll make sure he knows just how ignorant his senior officers are!’

The door banged behind him with a force which set the coffee cups on Parslow’s desk vibrating.

‘Now I’d say you handled that really well, Dog,’ said the superintendent mildly.

Dog shrugged.

‘You’ve got to play ’em as you see ’em,’ he said.

‘One of your famous Uncle Endo’s gems, is it?’ enquired Parslow. ‘All right, fill me in.’

He listened, sucking reflectively on a tablet.

‘Sounds like it could turn out nasty,’ he said unhappily. ‘Maguire. Is she Irish?’

‘Born in Londonderry, brought up in Northampton.’

‘Is that a problem for you, Dog?’

‘No,’ he said emphatically. Too emphatically? But Parslow just wanted formal reassurance.

‘Good. It’s an odd tale she tells, certainly. Over-ingenious, you reckon? Or odd enough to be true?’

It dawned on Dog that Parslow did not yet know that Maguire had walked out of the hospital.

He said, ‘Hardly matters, does it? One way the kid’s dead, the other, he’s likely to be in danger of his life.’

He saw Parslow register glumly that hassle awaited them in all directions, then tossed in his poison pill.

‘One more thing,’ he said. ‘I’ve just heard from Scott at the General that Maguire’s had it away on her toes.’

A spasm of pain crossed Parslow’s face, mental now but with its physical echoes not far behind. He should go, thought Dog. To hell with hanging on till he topped twenty-five years, which was Parslow’s avowed aim. But who the hell was he to give advice? Another month would see his ten years up, and for the past eighteen months he’d been promising himself that the decade was enough, he’d have done whatever he set out to do by joining. Only, his motives were now so distant, he couldn’t recall whether he’d achieved them or not.

Parslow said, ‘Have the press got a sniff yet?’

‘No. And I’d prefer to keep it low key till we know which way we’re going,’ said Dog.

‘Fine,’ said Parslow. ‘I suppose I’d better have a word with Mr Tredmill.’

He didn’t sound as if he relished the prospect. Everyone knew that the Chief Constable was keen for him to go and didn’t much mind if it was in an ambulance.

‘I’m going round to Maguire’s flat,’ said Dog.

‘You think she might show up there?’ said Parslow hopefully.

‘Only if she’s mad,’ said Dog.

Parslow popped another tablet into his mouth.

‘What makes you think she isn’t?’ he asked, sucking furiously. ‘And if she is mad, and she’s killed one kid, you’d better find her pretty damn quick, Dog, before she gets the urge to kill another!’

7

Jane Maguire’s head was aching. She wondered what the result of the X-ray had been. Most shops were already staying open late as Christmas approached and she went into a chemist’s and bought some aspirin. The shop was packaged for the festivities with golden angels dangling from the ceiling and carols booming out of the P. A. Noll was to have been an angel in the school nativity play on the last day of term this coming Thursday …

She had to get out of this perfumed brightness. Clutching her aspirins, she started to push through the thronging shoppers towards the door. Behind her someone called, ‘Excuse me …’ A woman said, ‘I think they want …’ but she thrust her rudely aside and did not pause till she was outside on the glistening pavement dragging in litres of the cold damp air.

A hand grasped her arm. She pulled it free, turned, only fear preventing her from screaming abuse. A girl in a blue overall looked at her strangely and said, ‘You forgot your change.’

She took the money and managed to croak a thank you. Despite the chill rain she felt hot and weak. Across the road was a pub. Oblivious of traffic she made her way towards it. Only when she reached the bar did she realize it was the same pub she’d been in this lunchtime. It seemed light years ago. Would the barman remember her? What if he did? There was hardly time for her face to have appeared in the papers.

She ordered a brandy. She didn’t like it, but her mother had always insisted on its medicinal qualities. Her mother … She took a sip and pulled a face. The barman said, ‘All right, is it?’ She said, ‘Yes. Sorry. It’s just the taste … I mean, I’m starting a cold …’

It was a productive lie. He said, ‘What you really need is something hot. We do coffee.’ And as he poured her a cup in response to her nod, she was able to take a couple of aspirin without him calling the drug squad.

She sipped the coffee and felt a little better. It occurred to her that the last time she had eaten had been in this place several hours ago, and that hadn’t been much. There were some corpse-pale pies in a plastic display cabinet. She asked for one. The barman put it in a microwave and a few moments later handed it to her, piping hot but still pale as death. She bit into it. The meat was stringy, the gravy slimy, but it tasted delicious. So. Forget the soul, forget the intellect. Animal pleasure was still possible even after …

She pushed the thought away as she ate the pie. Then she ordered another. No pleasure now, but a simple refuelling, an anticipation that she would need all her resources.

Finished, she went to the cloakroom. The mirror showed her a face as pallid as the pies. Her long red hair, usually electric with life, hung straight and lank and darkened almost to blackness by its exposure to the rain. It was, she guessed, a good enough disguise, but it was not how she cared to see herself. She stooped to get her head under the hand drier and combed her hair dry in the hot blast. Then she washed her face, rubbed it vigorously with a paper towel and applied a little make-up to her skin, which was glowing with friction.

Once more she inspected herself. It was better, this shell she had to present to the world. Little sign there of the hollow darkness beneath, empty of everything but the echo of a child crying …

Her clothing was very damp. She took off her linen jacket and dried it as best she could under the hand drier. Then she thought, ‘What the hell am I doing?’ It was these damp clothes that the fearsome Cicero would have a description of. Out there was the High Street full of shops desperate to take her money, no matter how tainted it might be.

She left the pub without re-entering the bar and half an hour later she had solved both the problems of damp and disguise. In black trainer-type shoes, loose slacks, tee shirt, and a chunky sweater, topped by a thigh-length waxed jacket with her hair tucked beneath its wired hood, she felt herself anonymous and warm. Her headache had gone and though she felt her body to be far from the high muscle tone she had enjoyed since her early teens, she was walking with some of her old long-limbed athleticism as she approached the bus station.

Despite the weather and the hour there were still plenty of people about, seduced by the lights and the music and the glittering prizes on offer in the late-closing stores. A couple in front of her turned aside abruptly to peer into a toy-shop window and in the gap created she glimpsed, twenty yards ahead at the bus station entrance, the tall helmets of a pair of policemen.

Immediately, without thinking, she too halted and turned towards the display of toy space ships, ray guns, spacemen helmets, all the TV-age artefacts designed to delight the heart of a little boy. Her brain refused to register them. Instead her head kept turning till she was looking back down the street. It felt like slow motion, but it all happened quickly enough for her to catch a man’s eyes before he too paused and looked aside into a shop window. That was all it took. He was an ordinary-looking man from what she could see of him under a narrow-brimmed tweed hat and a buttoned-up riding mac. But that brief eye contact was enough, even if the shop window he was peering into with such interest hadn’t been a ladies’ heel repair bar.

She glanced the other way. The helmets were moving towards her.

She peered into the toy-shop window. The toys presented no problem now. She couldn’t see them, only the street behind her reflected in the glass. The tall helmets like ships’ prows came alongside. They didn’t pause, but sailed on by. She didn’t wait to see what would happen when they reached the man outside the heel bar but strode out along the pavement, leg muscles tensing and untensing, almost trembling in their anticipation of being called upon to explode into a sprint. But she mustn’t draw attention to herself. Then, as she reached the station entrance, she saw at the far side the bus she wanted, the last couple of passengers stepping aboard.

Now she had her excuse. The legs stretched and she floated across the intervening fifty yards with the balanced grace of a ballet dancer.

The engine was running, the automatic doors closing. The driver saw her, decided it was near enough to Christmas for charity, and pressed the button to reopen the doors. She scrambled aboard.

The bus pulled out of the station with that minimal acknowledgement of the presence of other traffic which distinguishes the bus driver the whole world over.

Jane Maguire flopped into a seat and looked out of the window.

For the second time her eyes met those of the man in the tweed hat.

Then he was falling away behind her. She relaxed, or rather felt her body go weak. She tried to set her thoughts in order but found her mind had lost its strength too. The bus moved on through the garishly lit streets, then out of the town into the sealing darkness of the countryside, and Jane sat still, feeling herself more part of the country’s dark than the bus’s light, with little sense of either presence or progress, and unable even to tell whether she was hiding or seeking, chasing or chased.

8

Dog Cicero stood outside Maguire’s apartment block and felt his unhappiness grow. It was a modern three-storey building, purpose built, in a good residential area less than ten minutes’ drive from the kindergarten. Renting or buying, these flats would cost. Add the kindergarten fees … he had forgotten to check out her salary at the Health Centre but doubted if it would be enough to cover flat, school and food, clothing etc.

Maguire’s apartment was Number Seventeen on the top floor. He rang the bell, felt himself observed through the peephole, then DC Johnson opened the door.

‘Any action?’ asked Dog.

‘Nothing. There’s no phone, and you’d need to be a pretty thick kidnapper to knock at the door with a ransom note, wouldn’t you? Thousand to one it’s a weirdo anyway.’

Always interested in odds, Dog said, ‘Reason?’

‘I’ve had a poke around. Jackie Onassis she ain’t.’

Dog glanced round the room. It was clean, tidy and comfortable, but hardly suggestive of wealth worth extorting.

He said, ‘It may be neither. Take a stroll around the neighbours. Keep it low key but find out what they know about Maguire, when they last saw her and the kid, especially if anyone noticed her having trouble with her car this morning.’

Johnson, a plump, comfortable-looking man whose sleepy exterior belied a sharp mind, looked shrewdly at Dog and said, ‘She’s in the frame herself, is she, guv?’

‘Could be. One thing – she’s on the loose. I doubt if she’ll come back here, but keep your eyes skinned.’

He closed the door behind the plump DC and began to search the flat.

Johnson hadn’t poked deep enough. The clothes in the wardrobe might not be designer originals but the pegs they came off weren’t cheap. They all had American labels. The same went for most of the kid’s toys, expensive and made in the USA. Her lingerie was of the same quality. He looked without success for anything that might be professionally kinky. Nor did he find anything in the way of contraceptive medication or stocks of condoms to suggest a commercial sex life. Not even a domestic one. He searched diligently for drugs, both prescribed and proscribed, anything which would suggest nerves stretched close to breaking point, but found nothing more than a bottle of paracetamol and a child’s cough mixture. There was flour in the flour jar, tea in the tea caddy, talc in the talc tin, and nothing at all on top of the wardrobe, in the lavatory cistern or under the kitchen sink. There was no alcohol in the flat nor any tobacco. She had a small portable television set and a radio tuned to Radio Two. Her small tape collection was mainly soul and folk. There were quite a lot of books, mostly paperbacks. Her taste in fiction was for chunky historical romances, though he did find a couple of Booker nominees which she was either still reading or, on the evidence of the hairpin bookmarks, had abandoned at page seventeen and page thirty-two respectively. There were two PE manuals, one on athletics coaching, the other on sports injuries, both inscribed Jane Maguire, South Essex College of Physical Education. There was also a beautifully bound edition of Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience. It was inscribed, To Jane, going out into the world, with love and best wishes, Maddy. He opened it at random and found himself looking at a poem called ‘The Little Boy Lost’.

‘Father, father! where are you going?

O do not walk so fast.

Speak, father, speak to your little boy,

Or else I shall be lost.’

The night was dark, no father was there

He closed the book abruptly and sat down in an old armchair which creaked comfortably, and tried to think like a copper. He had found nothing remarkable, nothing incriminatory. The only oddness was an absence, not a presence.

There was no mail except the usual junk addressed to the occupier which he’d found in the kitchen pedal bin. But there was nothing to suggest that anything either official or personal had ever come addressed to Mrs Jane Maguire.

And there was nothing either which referred to her dead husband, Oliver Beck.

He closed his eyes and played through what he had got, but it came out blurred and distorted with too much interference from other channels.

He’d told Parslow that Maguire’s Irish background was no problem, and he’d meant it. But then his eyes had been wide open and he’d been able to blot out the mental image of a tall, graceful woman with huge green eyes and hair aflame like a comet’s tail …

He opened his eyes abruptly and found to his surprise that he had rolled and lit one of his capillary cigarettes.

There were no ashtrays. Maguire didn’t smoke, probably didn’t like the smell of tobacco in her home. He experienced an absurd guilt, told himself she wasn’t going to be back here soon enough to notice, and felt guiltier still.

He went into the kitchen and flushed the butt down the sink. Then he put the kettle on and made a cup of very strong coffee.

As he drank it Johnson returned.

‘You’ve been quick,’ said Dog.

‘I’ve not been on house to house,’ said the constable defensively. ‘Just the other flats, and at half of them I got no answer, and as good as none at a lot of the rest. I only managed to raise three who admitted ever having noticed Maguire. First was an old lady called Ashley who is more or less confined to the flat beneath. Didn’t know Maguire by name but says that she’s heard a child crying in the flat above on several occasions and the mother shouting angrily, after which the crying died to a whimper. She says she got so concerned last week that she rang the council’s Social Service department and reported it.’

‘Any action?’ asked Dog.

‘She says someone came round on Saturday morning but couldn’t get any answer from Maguire’s flat. But later she claims she saw Maguire putting the child into her car and driving away.’