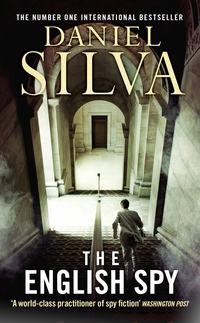

Полная версия

The English Spy

He spent the remainder of that night on the veranda of his cottage, reading by the light of his hurricane lamp. And at the top of every hour, he lowered his book and listened to the news on the BBC as the waves slapped and receded on the beach and the palm fronds hissed in the night wind. In the morning, after an invigorating swim in the sea, he showered, dressed, and packed his belongings into his canvas duffel: his clothing, his books, his radio. In addition, he packed two items that had been left for him on the islet of Tortu: a Stechkin 9mm pistol with a silencer screwed into the barrel, and a rectangular parcel, twelve inches by twenty. The parcel weighed sixteen pounds exactly. He placed it in the center of the duffel so it would remain balanced when carried.

He left the beach at Lorient for the last time at half past seven and, with the duffel resting upon his knees, rode into Gustavia. The Aurora sparkled at the edge of the harbor. He boarded at ten minutes to eight and was shown to his cabin by his sous-chef, a thin English girl with the unlikely name Amelia List. He stowed his possessions in the cupboard—including the Stechkin pistol and the sixteen-pound parcel—and dressed in the chef’s trousers and tunic that had been laid upon his berth. Amelia List was waiting in the corridor when he emerged. She escorted him to the galley and led him on a tour of the dry goods pantry, the walk-in refrigerator, and the storeroom filled with wine. It was there, in the cool darkness, that he had his first sexual thought about the English girl in the crisp white uniform. He did nothing to dispel it. He had been celibate for so many months that he could scarcely recall what it felt like to touch a woman’s hair or caress the flesh of a defenseless breast.

A few minutes before ten o’clock there came an announcement over the ship’s intercom instructing all members of the crew to report to the afterdeck. The man called Colin Hernandez followed Amelia List outside and was standing next to her when two black Range Rovers braked to a halt at Aurora’s stern. From the first emerged two giggling sunburned girls and a pale florid-faced man in his forties who was holding the straps of a pink beach bag in one hand and the neck of an open bottle of champagne in the other. Two athletic-looking men spilled from the second Rover, followed a moment later by a woman who looked to be suffering from a case of terminal melancholia. She wore a peach-colored dress that left the impression of partial nudity, a wide-brimmed hat that shadowed her slender shoulders, and large opaque sunglasses that concealed much of her porcelain face. Even so, she was instantly recognizable. Her profile betrayed her, the profile so admired by the fashion photographers and the paparazzi who stalked her every move. There were no paparazzi present that morning. For once she had eluded them.

She stepped aboard the Aurora as though she were stepping over an open grave and slipped past the assembled crew without a word or glance, passing so close to the man called Colin Hernandez he had to suppress an urge to touch her to make certain she was real and not a hologram. Five minutes later the Aurora eased into the harbor, and by noon the enchanted island of Saint Barthélemy was a lump of brown-green on the horizon. Stretched topless upon the foredeck, drink in hand, her flawless skin baking in the sun, was the most famous woman in the world. And one deck below, preparing an appetizer of tuna tartare, cucumber, and pineapple, was the man who was going to kill her.

2

OFF THE LEEWARD ISLANDS

EVERYONE KNEW THE STORY. AND even those who pretended not to care, or expressed disdain over her worldwide cult of devotion, knew every sordid detail. She was the immensely shy and beautiful middle-class girl from Kent who had managed to find her way to Cambridge, and he was the handsome and slightly older future king of England. They had met at a campus debate having something to do with the environment, and, according to the legend, the future king was instantly smitten. A lengthy courtship followed, quiet and discreet. The girl was vetted by the future king’s people; the future king, by hers. Finally, one of the naughtier tabloids managed to snap a photograph of the couple leaving the Duke of Rutland’s annual summer ball at Belvoir Castle. Buckingham Palace released a bland piece of paper confirming the obvious, that the future king and the middle-class girl with no aristocratic blood in her veins were dating. Then, a month later, with the tabloids ablaze with rumors and speculation, the palace announced that the middle-class girl and the future king planned to marry.

They were wed at St. Paul’s Cathedral on a morning in June when the skies of southern England poured with black rain. Later, when things fell apart, there were some in the British press who would write that they were doomed from the start. The girl, by temperament and breeding, was wholly unsuited for life in the royal fishbowl; and the future king, for all the same reasons, was equally unsuited for marriage. He had many lovers, too many to count, and the girl punished him by taking one of her security guards to her bed. The future king, when told of the affair, banished the guard to a lonely outpost in Scotland. Distraught, the girl attempted suicide by taking an overdose of sleeping tablets and was rushed to the emergency room at St. Anne’s Hospital. Buckingham Palace announced she was suffering from dehydration caused by a bout of influenza. When asked to explain why her husband had not visited her in the hospital, the palace murmured something about a scheduling conflict. The statement raised far more questions than it answered.

Upon her release, it became obvious to royal watchers that all was not well with the future king’s beautiful wife. Even so, she performed her marital duty by bearing him two heirs, a son and a daughter, both delivered after abbreviated and difficult pregnancies. The king showed his gratitude by returning to the bed of a woman to whom he had once proposed marriage, and the princess retaliated by attaining a global celebrity that eclipsed that of the king’s sainted mother. She traveled the world in support of noble causes, a horde of reporters and photographers hanging on her every word and movement, and yet all the while no one seemed to notice she was sliding toward something like madness. Finally, with her blessing and quiet assistance, it all came spilling onto the pages of a tell-all book: her husband’s infidelities, the bouts of depression, the suicide attempts, the eating disorder brought on by her constant exposure to the press and public. The future king, incensed, engineered a stream of retaliatory press leaks about his wife’s erratic behavior. Then came the coup de grâce, the recording of a passionate telephone conversation between the princess and her favorite lover. By then, the Queen had had enough. With the monarchy in jeopardy, she asked the couple to divorce as quickly as possible. They did so a month later. Buckingham Palace, without a trace of irony, issued a statement declaring the termination of the royal marriage “amicable.”

The princess was permitted to keep her apartments in Kensington Palace but was stripped of the title Her Royal Highness. The Queen offered her a second-tier honorific but she refused it, preferring instead to be called by her given name. She even shed her SO14 bodyguards, for she viewed them more as spies than protectors of her security. The palace quietly kept tabs on her movements and associations, as did British intelligence, which viewed her more as a nuisance than a threat to the realm.

In public, she was the radiant face of global compassion. But behind closed doors she drank too much and surrounded herself with an entourage that one royal adviser described as “Eurorubbish.” On this trip, however, her retinue of companions was smaller than usual. The two sunburned women were childhood friends; the man who boarded Aurora with an open bottle of champagne was Simon Hastings-Clarke, the grotesquely wealthy viscount who supported her in the style to which she had become accustomed. It was Hastings-Clarke who flew her privately around the world on his fleet of jets, and Hastings-Clarke who footed the bill for her bodyguards. The two men who accompanied them to the Caribbean were employed by a private security firm in London. Before leaving Gustavia, they had subjected the Aurora and its crew to only a cursory inspection. Of the man called Colin Hernandez, they asked a single question: “What are we having for lunch?”

At the request of the former princess, it was a light buffet, though neither she nor her companions seemed terribly interested in it. They drank a great deal that afternoon, roasting their bodies in the harsh sun of the foredeck, until a rainstorm drove them laughing to their staterooms. They remained there until nine that evening, when they emerged dressed and groomed as though for a garden party in Somerset. They had cocktails and canapés on the afterdeck and then repaired to the main salon for dinner: salad with truffle-infused vinaigrette, followed by lobster risotto and rack of lamb with artichoke, lemon forte, courgette, and piment d’argile. The former princess and her companions declared the meal magnificent and demanded an appearance by the chef. When finally he appeared, they serenaded him with childlike applause.

“What will you make us tomorrow night?” asked the former princess.

“It’s a surprise,” he replied in his peculiar accent.

“Oh, good,” she said, fixing him with the same smile he had seen on countless magazine covers. “I do like surprises.”

They were a small crew, eight in all, and it was the responsibility of the chef and his assistant to see to the china, the stemware, the silver, the pots and pans, and the cooking utensils. They stood side by side at the basin long after the former princess and her companions had turned in, their hands occasionally touching beneath the warm soapy water, her bony hip pressing against his thigh. And once, as they squeezed past one another in the linen cabinet, her firm nipples traced two lines across his back, sending a charge of electricity and blood to his groin. They retired to their cabins alone, but a few minutes later he heard a butterfly tap at his door. She took him without a sound. It was like performing the act of love with a mute.

“Maybe this was a mistake,” she whispered into his ear when they had finished.

“Why would you say that?”

“Because we’re going to be working together for a long time.”

“Not so long.”

“You’re not planning to stay?”

“That depends.”

“On what?”

He said nothing more. She laid her head on his chest and closed her eyes.

“You can’t stay here,” he said.

“I know,” she answered drowsily. “Just for a little while.”

He lay motionless for a long time after, Amelia List sleeping on his chest, the Aurora rising and falling beneath him, his mind working through the details of what was to come. Finally, at three o’clock, he eased from the berth and padded naked across the cabin to the cupboard. Soundlessly, he dressed in black trousers, a woolen sweater, and a dark waterproof coat. Then he removed the wrapper from the parcel—the parcel measuring twelve inches by twenty and weighing sixteen pounds precisely—and engaged the power source and the timer on the detonator. He returned the parcel to the cupboard and was reaching for the Stechkin pistol when he heard the girl stir behind him. He turned slowly and stared at her in the darkness.

“What was that?” she asked.

“Go back to sleep.”

“I saw a red light.”

“It was my radio.”

“Why are you listening to the radio at three in the morning?”

Before he could answer, the bedside lamp flared. Her eyes flashed across his dark clothing before settling on the silenced gun that was still in his hand. She opened her mouth to scream, but he placed his palm heavily across her face before any sound could escape. As she struggled to free herself from his grasp, he whispered soothingly into her ear. “Don’t worry, my love,” he was saying. “It will only hurt a little.”

Her eyes widened in terror. Then he twisted her head violently to the left, severing her spinal cord, and held her gently as she died.

It was not the custom of Reginald Ogilvy to stand the lonely hours of the middle watch, but concern for the safety of his famous passenger drove him to the bridge of the Aurora early that morning. He was checking the weather forecast on an onboard computer, a fresh cup of coffee in his hand, when the man called Colin Hernandez appeared at the top of the companionway, dressed entirely in black. Ogilvy looked up sharply and asked, “What are you doing here?” But he received no reply other than two rounds from the silenced Stechkin that pierced the front of his uniform and mauled his heart.

The coffee cup clattered loudly to the floor; Ogilvy, instantly dead, thudded heavily next to it. His killer moved calmly to the console, made a slight adjustment to the ship’s heading, and retreated down the companionway. The main deck was deserted, no other crew members on duty. He lowered one of the Zodiac dinghies into the black sea, clambered aboard, and released the line.

Adrift, he bobbed beneath a canopy of diamond-white stars, watching the Aurora slicing eastward toward the shipping lanes of the Atlantic, pilotless, a ghost ship. He checked the luminous face of his wristwatch. Then, when the dial read zero, he looked up again. Fifteen additional seconds elapsed, enough time for him to consider the remote possibility that the bomb was somehow defective. Finally, there was a flash on the horizon—the blinding white flash of the high explosive, followed by the orange-yellow of the secondary explosions and fire.

The sound was like the rumble of distant thunder. Afterward, there was only the sea beating against the side of the Zodiac, and the wind. With the press of a button, he fired the outboard and watched as the Aurora started her journey to the bottom. Then he turned the Zodiac to the west and opened the throttle.

3

THE CARIBBEAN–LONDON

THE FIRST INDICATION OF TROUBLE came when Pegasus Global Charters of Nassau reported that a routine message to one of its vessels, the 154-foot luxury motor yacht Aurora, had received no reply. The Pegasus operations center immediately requested assistance from all commercial ships and pleasure craft in the vicinity of the Leeward Islands, and within minutes the crew of a Liberian-registered oil tanker reported that they had seen an unusual flash of light in the area at approximately 3:45 that morning. Shortly thereafter the crew of a container ship spotted one of the Aurora’s dinghies floating empty and adrift approximately one hundred miles south-southeast of Gustavia. Simultaneously, a private sailing vessel encountered life preservers and other floating debris a few miles to the west. Fearing the worst, Pegasus management phoned the British High Commission in Kingston and informed the honorary consul that the Aurora was missing and presumed lost. Management then sent along a copy of the passenger manifest, which included the given name of the former princess. “Tell me it isn’t her,” the honorary consul said incredulously, but Pegasus management confirmed that the passenger was indeed the former wife of the future king. The consul immediately rang his superiors at the Foreign Office in London, and the superiors determined the situation was of sufficient gravity to wake Prime Minister Jonathan Lancaster, at which point the crisis truly began.

The prime minister broke the news to the future king by telephone at half past one, but waited until nine to inform the British people and the world. Standing outside the black door of 10 Downing Street, his face grim, he recounted the facts as they were known at that time. The former wife of the future king had traveled to the Caribbean in the company of Simon Hastings-Clarke and two other longtime friends. On the holiday island of Saint Barthélemy, the party had boarded the luxury motor yacht Aurora for a planned one-week cruise. All contact with the vessel had been lost; surface debris had been discovered. “We hope and pray the princess will be found alive,” the prime minister said solemnly. “But we must prepare ourselves for the very worst.”

The first day of the search produced no remains or survivors. Nor did the second day or the third. After conferring with the Queen, Prime Minister Lancaster announced that his government was operating under the assumption that the beloved princess was dead. In the Caribbean, the search teams focused their efforts on finding wreckage rather than the bodies. It would not be a long search. In fact, just forty-eight hours later, an unmanned submersible operated by the French navy discovered the Aurora lying beneath two thousand feet of seawater. One expert who viewed the video images said it was clear the vessel had suffered some type of cataclysmic failure, almost certainly an explosion. “The question is,” he said, “was it an accident, or was it intentional?”

A majority of the country—reliable polling said it was so—refused to believe she was actually gone. They hung their hopes on the fact that only one of the Aurora’s two Zodiac dinghies had been found. Surely, they argued, she was adrift on the open seas or had washed ashore on a deserted island. One disreputable Web site went so far as to report that she had been spotted on Montserrat. Another said she was living quietly by the sea in Dorset. Conspiracy theorists of every stripe concocted lurid tales of a plot to kill the princess that was conceived by the Queen’s Privy Council and carried out by Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service, better known as MI6. Pressure mounted on its chief, Graham Seymour, to issue a full-throated denial of the allegations, but he steadfastly refused. “These aren’t allegations,” he told the foreign secretary during a tense meeting at the service’s vast riverfront headquarters. “These are fairy tales spun by people with mental disorders, and I won’t dignify them with a response.”

Privately, however, Seymour had already reached the conclusion that the explosion aboard the Aurora was not an accident. So, too, had his counterpart at the DGSE, the highly capable French intelligence service. A French analysis of the wreckage video had determined that the Aurora was blown apart by a bomb detonated belowdecks. But who had smuggled the device aboard the vessel? And who had primed the detonator? The DGSE’s prime suspect was the man who had been hired to replace the Aurora’s missing head chef on the evening before the yacht left port. The French forwarded to MI6 a grainy video of his arrival at Gustavia’s airport, along with a few poor-quality still photos captured by private storefront security cameras. They showed a man who did not care to have his picture taken. “He doesn’t strike me as the sort of chap who would go down with the ship,” Seymour told a gathering of his senior staff. “He’s out there somewhere. Find out who he really is and where he’s hiding out, preferably before the Frogs.”

He was a whisper in a half-lit chapel, a loose thread at the hem of a discarded garment. They ran the photographs through the computers. And when the computers failed to find a match, they searched for him the old-fashioned way, with shoe leather and envelopes filled with money—American money, of course, for in the nether regions of the espionage world, dollars remained the reserve currency. MI6’s man in Caracas could find no trace of him. Nor could he find any hint of an Anglo-Irish mother with a poetic heart, or of a Spanish-businessman father. The address on his passport turned out to be a derelict lot in a Caracas slum; his last known phone number was long deceased. A paid asset inside the Venezuelan secret police said he’d heard a rumor about a link to Castro, but a source close to Cuban intelligence murmured something about the Colombian cartels. “Maybe once,” said an incorruptible policeman in Bogotá, “but he parted company with the drug lords a long time ago. The last thing I heard, he was living in Panama with one of Noriega’s former mistresses. He had several million stashed in a dirty Panamanian bank and a beach condo on the Playa Farallón.” The former mistress denied all knowledge of him, and the manager of the bank in question, after accepting a bribe of ten thousand dollars, could find no record of any accounts bearing his name. As for the beach condo in Farallón, a neighbor could recall little of his appearance, only his voice. “He spoke with a peculiar accent,” he said. “It sounded as though he was from Australia. Or was it South Africa?”

Graham Seymour monitored the search for the elusive suspect from the comfort of his office, the finest office in all spydom, with its English garden of an atrium, its enormous mahogany desk used by all the chiefs who had come before him, its towering windows overlooking the river Thames, and its stately old grandfather clock constructed by none other than Sir Mansfield Smith Cumming, the first “C” of the British Secret Service. The splendor of his surroundings made Seymour restless. In his distant past, he had been a field man of some repute—not for MI6 but for MI5, Britain’s less glamorous internal security service, where he had served with distinction before making the short journey from Thames House to Vauxhall Cross. There were some in MI6 who resented the appointment of an outsider, but most saw “the crossing,” as it became known in the trade, as a sort of homecoming. Seymour’s father had been a legendary MI6 officer, a deceiver of the Nazis, a shaper of events in the Middle East. And now his son, in the prime of life, sat behind the desk before which Seymour the Elder had stood, cap in hand.

With power, however, there often comes a feeling of helplessness, and Seymour, the espiocrat, the boardroom spy, soon fell victim to it. As the search ground futilely on, and as pressure from Downing Street and the palace mounted, his mood grew brittle. He kept a photo of the target on his desk, next to the Victorian inkwell and the Parker fountain pen he used to mark his documents with his personal cipher. Something about the face was familiar. Seymour suspected that somewhere—on another battlefield, in another land—their paths had crossed. It didn’t matter that the service databases said it wasn’t so. Seymour trusted his own memory over the memory of any government computer.

And so, as the field hands chased down false leads and dug dry wells, Seymour conducted a search of his own from his gilded cage atop Vauxhall Cross. He began by scouring his prodigious memory, and when it failed him, he requested access to a stack of his old MI5 case files and searched those, too. Again he found no trace of his quarry. Finally, on the morning of the tenth day, the console telephone on Seymour’s desk purred sedately. The distinctive ringtone told him the caller was Uzi Navot, the chief of Israel’s vaunted secret intelligence service. Seymour hesitated, then cautiously lifted the receiver to his ear. As usual, the Israeli spymaster didn’t bother with an exchange of pleasantries.

“I think we might have found the man you’re looking for.”

“Who is he?”

“An old friend.”

“Of yours or ours?”

“Yours,” said the Israeli. “We don’t have any friends.”

“Can you tell me his name?”

“Not on the phone.”