Полная версия

Revolution 2.0

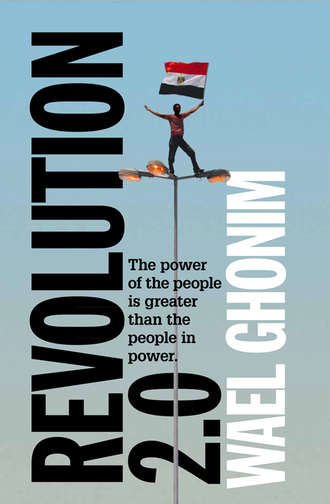

“Kullena Khaled Said”

ON JUNE 8, 2010, while browsing on Facebook, I saw a shocking image that a friend of mine had posted on my wall. The picture linked to the official Facebook account of Dr. Ayman Nour, the former presidential candidate who was a political activist. It was a horrifying photo showing the distorted face of a man in his twenties. There was a big pool of blood behind his head, which rested on a chunk of marble. His face was extremely disfigured and bloodied; his lower lip had been ripped in half, and his jaw was seemingly dislocated. His front teeth appeared to be missing, and it looked as if they had been beaten right out of his mouth. The image was so gruesome that I wondered if he had been wounded in war. But by accessing Dr. Nour’s page I learned that Khaled Mohamed Said had apparently been beaten to death on June 6 by two secret police officers in Alexandria.

My first reaction was denial. I could not believe that anyone could actually inflict such brutality on someone else. The victim was a twenty-eight-year-old from Alexandria. According to eyewitnesses, some dispute had erupted between him and the two officers, leading to their physical assault on him, which claimed the young man’s life.

I felt miserable, frustrated, and outraged. This was all the result of a political situation that rendered security forces loyal servants of an oppressive regime. Some of our law enforcement personnel had mutated into vicious monsters who were immune from punishment and prone to committing atrocities. They abandoned the Egyptian ethic of goodness that has pervaded our society for centuries.

My memory of that day is vivid. I was sitting in my small study in Dubai, unable to control the tears flowing from my eyes. My wife came in to see what was wrong. When I showed her Khaled Said’s picture, she was taken aback and asked me to stop looking at it. She left the room, and I continued to cry over the state of our nation and the widespread tyranny. For me, Khaled Said’s image offered a terrible symbol of Egypt’s condition.

I could not stand by passively in the face of such grave injustice. I decided to employ all my skills and experience to demand justice for Khaled Said and to help expose his story to vigorous public debate. It was time to lay bare the corrupt practices of the Ministry of Interior, our repressive regime’s evil right hand.

The logical first idea was to publish news of Khaled Said’s murder on Dr. Mohamed ElBaradei’s Facebook page, whose members exceeded 150,000 at that time, but I reasoned that doing so would exploit an event of national concern for political gain. I discovered that a page had been launched under the title “My Name Is Khaled Mohamed Said.” I browsed among the posts on that page. It was evident that the contributors were political activists. Their discourse was confrontational, beginning with the page’s headline: “Khaled’s murder will not go unpunished, you dogs of the regime.” From experience I knew that such language would not help in making the cause a mainstream one.

I decided to create another page and to use all my marketing experience in spreading it. Out of the many options I considered for the page’s name, “Kullena Khaled Said” — “We Are All Khaled Said” — was the best. It expressed my feelings perfectly. Khaled Said was a young man just like me, and what happened to him could have happened to me. All young Egyptians had long been oppressed, enjoying no rights in our own homeland. The page name was short and catchy, and it expressed the compassion that people immediately felt when they saw Khaled Said’s picture. I deliberately concealed my identity, and took on the role of anonymous administrator for the page.

The first thing I posted on the page was direct and blunt. It voiced the outrage and sadness that I felt.

Today they killed Khaled. If I don’t act for his sake, tomorrow they will kill me.

In two minutes’ time three hundred members had joined the page:

People, we became 300 in two minutes. We want to be 100,000. We must unite against our oppressor

I wrote the first article on the page: “You People Deprived of Humanity, We Will Extract Justice for Khaled Said.” It was an emotional, spontaneous piece of writing. I vowed that I would not personally abandon the fight for Khaled until his attackers were punished. The response was instant, and within a single hour the number of members climbed to three thousand.

Egyptians, my justice is in your hands.

I spoke on the page in the first person, posing as Khaled Said. What drove me, more than anything else, was the thought that I could speak for him, and if even a single victim of the regime could have the chance to defend himself, it would be a turning point. Speaking as Khaled gave me a liberty that I did not have on ElBaradei’s quasi-official page. It also had greater impact on the page’s members. It was as though Khaled Said was speaking from his grave.

Even though I was proficient at classical Arabic (al-fusHa) from my school years in Saudi Arabia, I chose to write my posts on “Kullena Khaled Said” in the colloquial Egyptian dialect that is closer to the hearts of young Egyptians. For the generation born in the eighties and nineties, classical Arabic is a language read in the newspapers or heard during news reports on television and comes across as quite formal. By using colloquial Egyptian, I aimed to overcome any barriers between supporters of the cause and myself. I also deliberately avoided expressions that were not commonly used by the average Egyptian or that were regularly used by activists, like nizaam, the Arabic word for “regime.” I was keen to convey to page members the sense that I was one of them, that I was not different in any way. Using the pronoun I was critical to establishing the fact that the page was not managed by an organization, political party, or movement of any kind. On the contrary, the writer was an ordinary Egyptian devastated by the brutality inflicted on Khaled Said and motivated to seek justice. This informality contributed to the page’s popularity and people’s acceptance of its posts.

The number of responses, and the incredible speed with which they came, indicated that administering “Kullena Khaled Said” was going to take a lot more time and effort than administering the ElBaradei page. I definitely needed help, and my experience thus far with AbdelRahman Mansour made him the perfect choice. I added him as the page’s second admin. During the first few weeks AbdelRahman was quite busy with school and other commitments, but he tried his best to help whenever needed.

I closely monitored news on the case and found the prosecutor’s report that acquitted the police force. I wrote:

The prosecution issued a preliminary report that the cause of death was drug overdose. Not only have you murdered me, but you also want to stain my reputation? God will reveal the truth and repay your lack of conscience.

Mostafa al-Nagar, ElBaradei’s campaign manager at the time, had written a moving article on his personal page entitled “We Are the Murderers of Khaled Said” after he visited Alexandria to verify the story. I published the article on my page without mentioning the writer’s name. I did not want people to make the link between al-Nagar and the page and eventually identify the anonymous administrator.

As the page’s membership base grew, so did my personal commitment. I felt the stirrings of a rare opportunity to make a difference and to combat oppression and torture. I was angry, and I was not the only one. On its first day, 36,000 people joined the page. Some of them wanted to learn more details about the case, some sought to offer sympathy and support, and others joined out of curiosity because they had received an invitation from a Facebook friend. Images of Khaled before and after the assault spread like wildfire. Similar crimes had taken place in the past, all too frequently, yet their stories had not spread too widely. It was the visual documentation of Khaled’s terrible death, along with the fact that he was from the middle class, that catalyzed this huge reaction. The image was impossible to forget, and thanks to social media, it was proliferating like crazy.

By the end of the first day there were more than 1,800 comments on the page. Some people wondered why another page had been launched when the first one, “My Name Is Khaled Mohamed Said,” had already reached 70,000 members. “Why not unite our efforts?” they asked. I considered joining forces and closing the page I had created. Yet the aggressive tone adopted by the first page continued to worry me.

I advertised “My Name Is Khaled Mohamed Said” on “Kullena Khaled Said” and declared that we all worked for a common cause. I urged people to link to the page and requested that we all coordinate our efforts. To my delight, the admins of the other page reciprocated. It was becoming obvious that this cause could unite a lot of people.

Several prominent opposition politicians publicly condemned Khaled Said’s brutal killing. Also, a public funeral for Khaled had been announced for Friday, June 11. I publicized the funeral on the page and asked that as many people as possible attend. I also posted an edited video of various acts of torture by members of the police force, in the hope that Egyptians would finally confront the dark side of the regime and realize that any one of us could be the next victim.

About a thousand people, many of them political activists, took part in the Alexandria funeral. A protest to denounce Khaled Said’s murder was also organized in Cairo by the April 6 Youth Movement, among other groups and activists. My hopes for justice were rising steadily. I asked the page members to join the protest, which was planned to take place outside the Ministry of Interior. But the security forces were prepared and decisive: they arrested many protesters and surrounded the rest with double their number of police officers, nearly making a perfect circle. From afar — as later seen in a photograph — the image was quite symbolic. It perfectly represented what the regime was doing to our country. Worse yet, the media, under the usual pressure from State Security, ignored the protest. As with many past examples of human rights abuses, the public was kept in the dark.

The media’s suppression of the physical world made the virtual world a critical alternative for promoting the cause. On the Facebook page, I began to focus on the notion that what had happened to Khaled was happening on a daily basis, in different ways, to people we never heard about. Torture is both systematic and methodical at the Ministry of Interior, I said. One of my most significant resources was the “Egyptian Conscience” blog, Misr Digital, by Wael Abbas. From 2005 to 2008, Wael Abbas actively published every torture document, image, or video that he received from anonymous sources. He was arrested several times by State Security, yet he and other brave bloggers continued to expose the horrifying violations of human rights that were taking place in Egypt.

I apologize for posting pictures of torture cases, but I swear that I had not seen most of them before. It seems I lived on another planet … A planet where I went to work in the morning and watched soccer games and sat at cafés with friends at night … And I used to think people who discussed politics had nothing better to do … But I am appalled to see a terrifying Egypt that I never knew existed … But by God, we will change it!

I posted links to other torture videos, which were numerous and easy to find. One of them that I published on the page was removed from YouTube, I noticed, because it violated that site’s content policies. Many users had reported it as an inappropriate and gruesome video. I did not try to use my employment at Google to resist this decision in any way; my activism had to remain independent of my job.

Meanwhile, although the official press remained utterly silent about Khaled Said’s case, the Ministry of Interior began to worry about the controversy. The authorities’ first line of defense: stain Khaled’s reputation. In an unprecedented public statement, the Ministry of Interior declared that the cause of Khaled’s death was not torture but rather asphyxiation, the result of swallowing a pack of marijuana. They said the facial deformation that appeared in the widely circulated photograph was the result of an autopsy. They claimed that Khaled Said had been wanted for four different crimes: drug-dealing, illegal possession of a weapon, sexual harassment, and evasion of military service. As a main player in the state-led defamation campaign, the state-owned Al-Gomhouriya newspaper then labeled Khaled Said “the Martyr of Marijuana,” a satirical reference to the activists’ name for him, “the Martyr of the Emergency Law.”

The circumstances of Khaled Said’s death were mysterious. According to eyewitnesses, he was sitting at an Internet café when two informers attacked and beat him severely. They then dragged him to the entrance of a nearby building, where they continued to pound him until he died. The official police account alleged that he had tried to hide a pack of marijuana by swallowing it, and that he choked and died while the informers were trying to force him to spit out the pack.

The ministry’s expected support of the secret police officers’ story, along with the defamation campaign launched against Khaled, exemplified its approach in addressing its problems: never admit guilt, even by a low-level officer. The very limited number of officers who were ever convicted in cases of torture generally returned to work as soon as their prison sentences came to an end.

In response to the ministry’s statement, Khaled Said’s mother spoke to the independent newspaper Al-Shorouk and dropped a bomb: she speculated that her son was murdered for possessing a video showing a local police officer and his secret police colleagues examining and then allegedly dividing confiscated drugs and money. Soon this video, which was allegedly found on Khaled Said’s cell phone, spread on Facebook. Many of those who shared it presented it as the reason behind his death. His friends claimed that Khaled had gotten this video by hacking into an informer’s cell phone. The video showed a police officer and a few others posing in front of a pile of marijuana and carrying some cash. The officer counted the number of people present and then counted the money and was seemingly about to divide it.

I quickly posted the video, presenting it as a potential explanation for the violence inflicted on Khaled. Yet members responded with disapproval, arguing that my accusations were not supported by clear evidence. I removed the video and posted an apology. It is true that I was quick to accuse the police, and that the officer’s actions in the video could have been interpreted differently. The page’s members thanked me for seeking the truth and not rushing to defame the police force. Nonetheless, the video spread widely on the Internet and was seen by more than 200,000 users in a few days.

Meanwhile, Khaled Said’s family went public with a copy of the military service certificate that proved that he had completed his compulsory service, directly countering an allegation made by the Ministry of Interior. I published the certificate on the Facebook page, as well as videos of three eyewitness accounts of Khaled’s murder. One of the witnesses was the Internet café owner, who said that the two secret police officers stormed the place and viciously attacked Khaled. He said he tried to interfere but that only increased their brutality. He also asserted that he did not see Khaled insert anything in his mouth. The second video featured a young boy who saw the beating and testified that others saw it as well but were too afraid to interfere. Finally, the third witness was the porter of the building where Khaled was brutally beaten. He described the viciousness of the violence and said that the officers beat Khaled’s head against the stairs while he yelled, “I will die!” But his cries did not deter them in any way. The porter said Khaled lost consciousness and might have died at that point. The ambulance arrived minutes later to carry his body away, without any interference from the residents.

Large numbers of new members were joining “Kullena Khaled Said” at unusually fast rates. The page did not belong to any specific patron, and I was careful not to use it for the benefit of any particular political cause, even the seven-demands petition. “Kullena Khaled Said” spoke the language of the Internet generation. The tone on the page was always decent and nonconfrontational. The page relied on the ongoing contributions of its members and established itself as the voice of those who despised the deterioration of Egypt, particularly as far as human rights were concerned.

Together, we wanted justice for Khaled Said and we wanted to put an end to torture. And social networking offered us an easy means to meet as the proactive, critical youth that we were. It also enabled us to defy the fears associated with voicing opposition. The virtual world seemed further from the oppressive reach of the regime, and therefore many were encouraged to speak up. The more difficult task remained, though, which was to transfer the struggle from the virtual world to the real one.

I was skeptical about supporting demonstrations, since the first one had had a disappointingly low turnout and had met with such a determined police crackdown. Though many activists had perceived it as a success — since it challenged the might of the ministry — I knew that average young Egyptians, such as the members of the Facebook page, would be easily demoralized if they were treated in a similar manner. Being an activist himself, AbdelRahman Mansour didn’t necessarily share that view, but we eventually agreed that it was important not to put our members at any risk whatsoever. So we chose instead to identify online activities that we could promote, to instill a sense of optimism and confidence that we could make a difference, even if only in the virtual world for the time being.

The first campaign I launched suggested that members of the page change their profile pictures to an anonymously designed banner of Khaled Said, featuring him against the backdrop of the Egyptian flag, with the caption “Egypt’s Martyr.” Thousands responded positively, including personal friends who had no idea that I was the page’s founder. Yet some members ridiculed the idea, calling it a helpless tactic in the face of the Ministry of Interior’s aggression. The fact remains, however, that our cause gained significant momentum through this awareness campaign.

The strategy for the Facebook page ultimately was to mobilize public support for the cause. This wasn’t going to be too different from using the “sales tunnel” approach that I had learned at school. The first phase was to convince people to join the page and read its posts. The second was to convince them to start interacting with the content by “liking” and “commenting” on it. The third was to get them to participate in the page’s online campaigns and to contribute to its content themselves. The fourth and final phase would occur when people decided to take the activism onto the street. This was my ultimate aspiration.

I remember debating about all this with Marwa Awad, a correspondent working for Reuters. I, of course, wore my Google hat at the time, and was speaking to her solely as an Internet expert. Marwa believed strongly in the need for change, but like many other Egyptians, she did not think that online activism could create the critical mass needed on the street for achieving real results. People feared the emergency law and the threat it posed to those who opposed the regime or its practices. Yet I was convinced that we could make the leap from the virtual world to the real one. It was going to happen someday, somehow.

The page needed to speak directly to its members and convince them to be active participants, and it was also important to break free from all the barriers of fear that controlled so many of us. So I came up with an idea that served both goals: I asked members to photograph themselves holding up a paper sign that said “Kullena Khaled Said.” Hundreds of members did so, and we began to publish their pictures on the page. The images created an impact many times stronger than any words posted on the page. Males and females of all backgrounds, aged between fourteen and forty, now personified the movement. The solidarity extended to expatriate Egyptians around the world and to Arabs in many countries — even Algeria, a soccer rival that had defeated Egypt in a World Cup qualifier, leading to heavy violence breaking out among the fans and to feelings of bitterness in citizens of both nations.

Isra, my seven-year-old daughter, had seen some of Khaled Said’s photos on my laptop and asked who he was. I explained that he was a good person killed by the police. She innocently said, “Aren’t the police supposed to be good? Don’t they protect the people?”

“Yes, but some policemen in Egypt are bad,” I replied.

Later that day, Isra came to my room to show me a drawing she had made. It showed a policeman shooting at a young man carrying the Egyptian flag. She told me that the young man was Khaled Said. I hugged her and told her how much I appreciated the fact that she cared about others, and that I was proud of the way she expressed solidarity with them using her own skills. I decided to post the drawing on “Kullena Khaled Said” and wrote that our coming generations would not tolerate humiliation and torture.

One picture the page received drove this point home; a pregnant woman sent us an ultrasonographic image of her fetus with a caption that read: “My name is Khaled, and I’m coming to the world in three months. I will never forget Khaled Said and I will demand justice for his case.”

The images worked like magic. Members thanked each other for their courage and solidarity. Such admiration and instant positive interaction encouraged even more members to post their pictures. The fact that the regime had not retaliated in any way also made it easier for many people to participate. The barriers of fear were slowly being torn down.

A few days following Khaled Said’s murder, opposition newspapers and some private television channels began supporting the cause. I asked page members to apply pressure to TV talk shows. Together, we compiled the telephone numbers of the different talk shows and posted them on the page. I encouraged everyone to call in and demand that show hosts discuss the case of Khaled Said. Earlier, some shows had attacked Khaled, while others had tried to remain neutral. A few had supported his cause, and we were hoping they would now increase in number.

The controversy grew. On June 15, Egypt’s public prosecutor transferred the case to special prosecution and ordered a second autopsy to confirm the cause of death. This decision amounted to a small victory for our cause and only served to excite us.