Полная версия

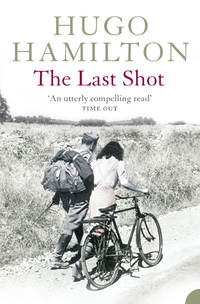

The Last Shot

The Last Shot

Hugo Hamilton

für Irmgard

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

About the Author

Praise

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

At 7.15 a.m. Bertha Sommer walked down the road from the main German garrison towards the town of Laun. She was on her way to the church of St Nicholas, where she would attend Mass, something she was determined not to miss no matter what events would take place on that day. ‘No matter how close the Russians are,’ she said to herself defiantly. It was a clear May morning: May 1945. The relentless rain of the night before had stopped, and even though banks of cloud still hung over the eastern sky, there was a feeling that the weather would change. An intuition of summer.

She was accompanied by an officer named Franz Kern whose noisy boots sometimes obscured the sound of her own footsteps. He was with her for her own protection. Her escort. The roads of Bohemia were no longer safe. And as they walked down the hill, the town of Laun was frozen below them in a patient immobility, blue woodsmoke rising above the roofs in the distance like a symbol of static hostility. The Czechs knew their day of freedom would come soon, but the feeling was tinged with the innate provincial fear which has clung to this small town ever since; the fear of being left behind by history. Time moves on, towns don’t.

The road was loud with birdsong. There was little to talk about as they walked. Bertha Sommer knew Officer Kern from the office where they saw each other regularly, though they seldom talked about anything other than official matters. Outside the office, there was nothing to say. In May 1945 there was so much on everybody’s mind. So much you couldn’t talk about. Or maybe it was the sheer volume of things to say that forced them instead to speak about nothing but the rain.

‘It kept me awake,’ she said openly. ‘I thought it would never end.’

Bertha was sure she had already said too much. It was followed by the silence along the road; their footsteps, the hysterical noise of birds and, somewhere in the distance, the familiar hoarse bark of a dog she had often heard before at this point on the road, but never actually seen. The rain had unleashed the fresh damp smell of the soil. It merged with the smell of exhaust left behind by military trucks.

In the small Bohemian town of Laun, where this story begins, somewhere almost halfway between Prague and Dresden, it was impossible to pretend that everything went on as normal. Europe was in ruins. Hitler was dead. There wasn’t much left of Dresden. The smell of Russian cigarettes came from the east, where the Red Army stood somewhere between Brno and Jih-lava, advancing at a rate of eighty kilometres per day. The smell of Camel cigarettes was even closer, drifting up from Pilsen in the south, where the Americans had stopped, having consented by nodding agreement that the liberation of Czechoslovakia belonged to the Russians. It was a matter of waiting. The radio stations coming from Dresden and from Prague went on broadcasting German march music. Occasionally you heard German swing. Mostly it was waltz music. The Reich was waltzing to an end.

The resistance movement in Czechoslovakia had planned their nationwide insurrection for that day. Everything was set for the liberation of Prague, the only European capital left under occupation. But the Reich held fast. There was talk of fighting to the last man. Orders were given by General Schörner in command of the German Army on the Eastern Front that any German soldier caught deserting or attempting to flee should be hanged on the spot. They were already dangling from the trees elsewhere, in Prussia. In defeat, the army hangs its own.

What everybody really wanted was to go home. The whole of Europe was thinking about home, or what was left of it. Bertha Sommer thought about Kempen, a small town no larger than Laun, but over 1,000 kilometres to the west, in the Rhineland. Officer Kern thought about Nuremberg, or what was left of it. Going home wasn’t that simple. Not so easy to end a war. A war is only over when the last shot has been fired, and who knows where the last shot of the Second World War was fired?

Back in April, when all German civilians were finally allowed to evacuate from the Czech protectorate back to German soil, the commander of the garrison at Laun issued a directive confining the remaining civilian backup personnel to barracks for their own safety. It could only have been intended for one person. Bertha Sommer. She was the last person left at the garrison of 2,000 infantry men of the 213th Battalion who could be described under this directive. She began to plead with Hauptmann Selders to be exempted. She was determined to go to Mass throughout the month of May. It was that important to her. Hauptmann Selders said he would hate to lose his last secretarial assistant to a partisan bullet along the open roads. But he was flexible and eventually changed the directive. From now on, he decreed that civilian backup personnel had to travel in armoured cars, until he reflected on the fuel shortages and changed his mind again; they had to be accompanied by an armed soldier. He put it in writing. She typed it up. Officer Franz Kern volunteered.

Bertha Sommer wore a three-quarter-length russet coat. In the early morning light along the road down to Laun, Officer Kern would have thought the colour of the coat leaned more towards burgundy or wine. But the exact colour of her coat had always been a matter of some dispute, ever since she bought it in Paris. Her own mother called it copper. The inhabitants of Laun, who were convinced that she was sent to the St Nicholas church to spy on them, said the coat was fox-red, or fox-brown.

Bertha Sommer walked briskly. Perhaps it was her shyness. She began to count her own footsteps. She idly measured the distance to the next building in footsteps; the first small house on the outskirts of the town.

‘Fräulein Sommer.’ Officer Kern addressed her quite abruptly. ‘Do you realize how close we are to the end?’

‘What do you mean?’ She was trying to read the implication.

‘It’s over. The Reich is finished. You have seen all the reports. It may not even last the day. Do you realize what this means for you?’

‘Yes and no.’

Occasionally their footsteps fell into unison, causing a slight embarrassment between them until her faster steps doubled his once more.

‘Fräulein Sommer, have you any idea how close we are to Russian captivity? For your sake, Fräulein Sommer, I would avoid this at all cost. Above all people, I would hate to see you taken into Russian hands.’

‘What are you suggesting?’ she said.

There was another moment of raw embarrassment. He apologized for putting it so crudely but he felt he had to warn her. Even then, his open discussion of German defeat was enough to condemn him for treason. Enough to have him shot or hanged from the next tree. Now she began to wonder why he had volunteered to walk down to the town with her. His honesty scared her. She suspected it was a trick. Something to test her loyalty. You could trust nobody in the Reich. And yet, he was only saying what everyone had felt privately for months.

‘Between the two of us, Fräulein Sommer, I think we should get out of Laun as soon as possible. Things are going to get very bad around here. I may be able to arrange something, so I would ask you to be prepared. The sooner we set off back towards Eger, to the German border, the better.’

‘Herr Kern, are you talking about desertion?’

‘Fräulein Sommer, I wish you wouldn’t put it like that. You are a civilian in the service of the Wehrmacht, how can you desert? There is no point in your being here with the army to the bitter end.

‘And it’s going to be bitter, believe me. I hear everything that’s going on. It’s my job to listen to all radio signals. I know what’s going to happen here when the Russians arrive. Very briefly, Fräulein Sommer, I have a simple plan to get you back to Germany. I may be able to arrange it tonight. Think about it. Don’t give me an answer now. Let it go through your head. But whatever happens, I would advise you to be ready to leave at a moment’s notice.’

Bertha said nothing. She kept walking as though she could pretend at any moment to have heard nothing. Why was this officer so interested in her welfare? She searched for motives. Gave no hint of collusion. She listened.

‘This may be your last chance to get back to Germany. The people in our garrison may never see their homes again…’ Officer Kern hesitated. ‘I want to offer you that chance, at least.’

When Officer Kern unexpectedly looked into her eyes she may have unconsciously given him some encouragement, because he began to unveil his plan as they walked.

‘At eleven o’clock this evening,’ he said, ‘you will see a Lazarett vehicle marked with the Red Cross by the main gates. It’s there every night. If you’re sitting in that truck by half-eleven, you’re with us. There are three of us. There is room for one more. Bring only one light bag and don’t let anyone see you.’

She acknowledged nothing and gave no indication whether she would be there or not. She felt that Officer Kern had shown her enormous trust. An almost indecent trust. She could have gone straight back and reported the plan, though it would be unlike her to do so. But she was afraid that she had already been dragged into a conspiracy by his talk. The fact that such an offer was put to her would force her to consider it. One way or the other, she would have to answer.

He told her to think it over. It was up to her. He would not be offended if she ignored it.

‘Just remember, Fräulein Sommer, when the Russians get to Laun, we can expect very little sympathy from them, or the Czechs. You know what’s happened around these parts. They’ll all be hungry for revenge. All these Sudeten Germans will be for it.’

She thought she knew what he was referring to. The occupation of Czechoslovakia. She knew nothing more. She knew nothing of Theresienstadt, forty kilometres east of Laun along the same river. She could imagine nothing like it. She walked into the church. Officer Kern held the large oak door open for her, nodded and stepped back outside, where he waited for her to pray and make up her mind. He was Lutheran. He stood at the bottom of the steps outside.

Inside, Bertha Sommer kneeled once again before the massive wooden carving which covered the end wall of the church behind the altar. The interior of the church had become so familiar to her over the months she had spent in Laun that her opinions began to repeat themselves. The great wood carving seemed a little out of place for this small church; it belonged more to a cathedral. The May altar for Our Lady was decorated with extra flowers. She tried to keep her mind on the Mass. She tried to put everything secular out of her head.

If you want to know what Bertha Sommer did during the Second World War: she prayed. That morning, though, she could hardly concentrate. Nothing could keep out the fragile reality of her situation in Laun. She kept wondering whether she would ever see her home again; her mother, her sisters, her aunt, her home town of Kempen. Struck by a sudden impatience, she wanted to go home that minute, and involuntarily she began to weigh up Officer Kern’s plan for escape.

Bertha prayed for guidance. She expected somehow to be given a divine signal. During the course of Mass she changed her mind at least a half-dozen times. She could not come to terms with the idea of desertion. It was dishonest, and dangerous. She kept thinking about Officer Kern’s subversive proposal. Could she trust him, she wondered. She had nobody to talk to about it but God. She would let God decide.

2

The barber’s shop on Prag Strasse in Laun was busy that morning. It could have been taken for some kind of symbol or national expression of independence that men arrived early to get their hair cut. Apart from Mass at the church of St Nicholas, it was the only good excuse any man could invent to be seen so early. The horizontal blinds of this front-room barber’s shop gave an excellent view on to the main street, on to the pub across the road and everything that moved through the town.

There was a group of men waiting to have their hair cut, four men and a small Down’s Syndrome boy who stood by the window. They all had seen the new armoured patrol arrive to replace the night patrol on the square. And the German woman on foot, in her red coat, along with a German officer.

The men sat along a wooden bench and said nothing. They felt the silent, reflective moment that all men feel before their turn comes up in the barber’s chair, the moment preceding change. From time to time they found something to whisper about. Occasionally the barber joined in with a discreet word in somebody’s ear as he drew the sheet up and stuffed it into the collar of his next customer. But the clicking of scissors took over and covered everything with a feverish whisper of its own.

The boy with Down’s Syndrome clapped when his father settled into the barber’s chair. He ran back and forth to the window, excited about everything, occasionally receiving a smile of acknowledgement from the men along the bench. He had red hair. Saliva ran down to his chin and there was a damp stain on his chest where it collected. He was no more than four years of age. Born during the war. The very existence of a boy with Down’s Syndrome was an overt act of revolution in the Reich.

The Czech liberation came late. They could have waited for the Russians but they were anxious to strike a blow for independence. A home-made revolution.

Throughout April the resistance movement had obstructed German military movement by bombing railways, disabling locomotives, tanks, armoured units and generally supporting the Russian advance. The aim was to be a nuisance. They blew up fuel reserves, and when the German Army resorted to using alcohol to power their vehicles, the Czechs began to spill bottles and barrels of schnapps and slivovitz into the streets; bottles they would soon need to celebrate victory when they were eventually liberated.

The men in Laun were waiting for the signal. They were already aware that on the previous day men from the nearby mining town of Kladno had marched to Hriskov, south of Laun, with no more than a ration of cigarettes in their pockets, to take over the German arms dump there. The Czechs needed weapons. In Prague, they planned to fight with furniture. With barricades. In another north Bohemian town, the people tried to do without weapons altogether and came out on the streets for a peaceful protest, a premature but unsuccessful attempt at the velvet approach. General Schörner told his troops ‘to quell any such disturbances with the most ruthless force’.

The men at the barber’s shop in Laun were waiting for the right moment to assemble and form a National Committee of independent Czechoslovakia. All they needed was a leader. They sat watching the boy with Down’s Syndrome playing with the cords of the blinds by the window. The boy groaned in a world of his own. Occasionally, he turned around and addressed one of the men without the slightest hint of shyness, his upper lip drawn up toward his nose, genetically disfigured into a permanent smile.

‘Who’s next?’ the barber asked, knowing that a son follows after a father.

The boy sat down on his father’s knee and allowed the barber to hang a sheet around him and tuck it under the collar. It was all new to him. He was silent, reassured by his father’s words, until the barber began to clip rhythmically with the scissors. ‘There’s a good boy,’ the barber kept saying. But even before the scissors had touched the boy’s hair, he began to struggle and make life difficult. The white sheet had already come undone. There was no point in putting it back. Instead, the barber manoeuvred himself around the chair as best he could to try and get at the boy’s hair.

Both the father and the barber tried to distract the boy. ‘Look, look in the mirror. Look, there’s a good boy.’ The barber tapped the mirror with his scissors. ‘There’s a good boy. Nearly finished,’ he kept saying.

But the boy soon began to wail. Not so much like crying, but a solid howl; half fear and half mistrust. He kept looking around to see what was going on but he couldn’t understand the purpose of the scissors. He tried to free his arms from his father’s grip. Wisps of cut hair fell into his eyes, tickled his nose and his neck behind his collar. Nobody could explain it to him. The barber got a scented towel and wiped it over the boy’s face, taking away a mixture of saliva, cut hair and tears.

Another armoured car went by outside. The barber managed to deflect the boy’s attention for long enough to clip a semi-circle over the ears. The fingers of his left hand pinned the boy’s head down vigorously. But the sound of the scissors magnified in the boy’s ears to the size of shears and he resumed his howls, louder than ever.

The whole barber’s shop had become occupied with the boy’s haircut. Once again the barber made an attempt to distract the boy. He took out two ivory brushes, clacked them together and gave them to the boy. The barber rushed around, exploiting the moment. It was a race against time, before the boy dropped the brushes again and put his hands up. That was enough. His father released him and the boy jumped down, running into the centre of the room.

‘Vla, vla,’ he said, holding his ears, showing off his haircut to the men waiting on the bench.

That was the morning the Czechs finally decided to liberate themselves from the fascists and hand themselves over to the communists. The grand uprising in Prague had begun. The whole country was rising up in support. In Laun, a man named Jaroslav Süssmerlich walked into the pub U Somolu at 81 Prag Strasse and convened the first meeting of the National Committee. The men at the barber’s shop abandoned their places in the queue and joined him.

They demanded the immediate surrender. They wanted nothing but outright capitulation. By phone, Jaroslav Süssmerlich translated the anger of the town and told the Germans they were ready to attack the garrison. The men from Kladno had already taken the arms dump at Hriskov. But the German commander in Laun made it clear that he had no authority to capitulate until orders came from Prague; from the German High Command. Besides, they held a number of key prisoners; Czech resistance fighters. It became a hostage drama. Negotiations became a race against time. Nobody realized that the Russians were approaching from the north instead of the south.

3

Bertha Sommer emerged from the church of St Nicholas, pushing the heavy oak door like a child. The idea of heavy oak doors in churches is to make people feel small and innocent; children of God. She adjusted her hat, blessed herself from the font and looked down the steep concrete steps, where she saw an armoured car parked along the kerb. It was the only vehicle in the street. The engine was running. Officer Kern stood beside the driver and both of them looked up at her. There was something wrong. She knew it.

Around her, everything else in the street bore the inertia of centuries. The houses, the dusty windows, the grey roofs, all looked as though they would never change.

Bertha Sommer had a good nose. It was the way Officer Kern looked at her as she descended the church steps that told her something had changed. For a moment, she thought she was being arrested for betrayal of the Reich. Either that, or she was fleeing straight away, back to the German border. She told herself she didn’t care. After the initial fright, there is always a moment of indifference.

She smelled a wisp of woodsmoke drifting down the street. Nothing visible, beyond the faint blue tint in the distance above the houses. It was a reassurance. Bertha knew every kind of smoke. She had smelled all the different smokes of the war: gunsmoke, fires, scorched landscape, phosphor smoke; even the smell of burning hair. She feared and respected every smell. She then got the smell of Officer Kern’s cigarette. Kern looked serious. When he spoke to her, it was back to his official voice. The former intimacy was ignored. She expected the worst.

‘Fräulein Sommer, we have instructions to return to the garrison immediately. By right, I should have conveyed this to you without delay. We must go straight away.’

He held the door of the vehicle for her and whispered, as she held her hat to get in, ‘There’s nothing to worry about.’

Afterwards, she felt foolish to have mistrusted him so much. She felt naïve, and envied the way men always seemed to know everything first. Inside the church, she had been under the brief illusion that it was raining outside, only to come out and find the street dry and the sun trying to break through the clouds at last.

The driver turned the vehicle and headed back through the town, past the square, along the main street towards the hill leading up to the garrison.

‘Apparently there is something going on here in the town,’ Kern said to her in the back of the car. ‘Hauptmann Selders has ordered all personnel off the streets.’

Kern didn’t discuss it any more. She asked him what it meant but he put a finger over his lips and pointed at the silent driver. They all went mute and looked out of the windows. Bertha saw nothing. No sign of anything going on. At the end of the town, she spotted two women hanging out washing. On a wall, she saw a ginger-coloured cat preparing to jump down. Smoke rose from the last three chimneys in the town. Nothing would ever change the speed of smoke rising from a chimney on a calm day in May.

Her own life would soon accelerate beyond recognition. After months and months of waiting, since Christmas, she would finally move into a new, though perhaps uncertain future. Anything was better than waiting. She thought of Caen in Normandy where she had spent most of the war. And the trips to Paris which had been so exciting. Czechoslovakia had provided none of that excitement. It became the place to wait for the war to end. She could only think of home. She could only think of the frustrating irony that the car in which she sat was actually travelling in the wrong direction. East. Into the arms of the Russians.

She turned around to look through the back window at the town. It may be the last look, she thought. Everywhere Bertha Sommer went, she called things by a private, arcane name in her own mind. As the armoured car climbed the hill back towards the garrison, she looked back and called it: the hill of the last time looking back. The morning of the end of the Reich, she said to herself as they drove through the gates.