Полная версия

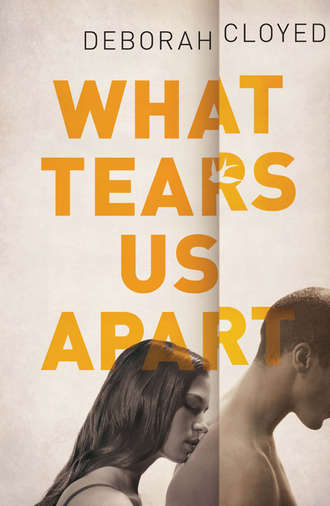

What Tears Us Apart

Love lives in the most dangerous places of the heart

The real world. That’s what Leda desperately seeks when she flees her life of privilege to travel to Kenya. She finds it at a boys’orphanage in the slums of Nairobi. What she doesn’t expect is to fall for Ita, the charismatic and thoughtful man who gave up his dreams to offer children a haven in the midst of turmoil.

Their love should be enough for one another—it embodies the soul-deep connection both have always craved. But it is threatened by Ita’s troubled childhood friend, Chege, a gang leader with whom he shares a complex history. As political unrest reaches a boiling point and the slum erupts in violence, Leda is attacked…and forced to put her trust in Chege, the one person who otherwise inspires anything but.

In the aftermath of Leda’s rescue, disturbing secrets are exposed, and Leda, Ita and Chege are each left grappling with their own regret and confusion. Their worlds upturned, they must now face the reality that sometimes the most treacherous threat is not the world outside, but the demons within.

What Tears us Apart

Deborah Cloyed

To debianca, and redbird.

Contents

Newswire

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Acknowledgments

Teaser

Questions for Discussion

A Conversation with Deborah Cloyed

Newswire America: December 31, 2007

NAIROBI, Kenya — Incumbent President Mwai Kibaki was hastily sworn in yesterday, beating out Raila Odinga in Kenya’s heated election. Allegations of fraud sparked violence countrywide.

In Kibera, one of the world’s largest slums and Raila Odinga’s stronghold, thousands flooded the streets, bearing rocks and machetes, chanting, “No Raila, no peace!”

Members of Raila’s Luo tribe lashed out at their Kikuyu neighbors—the tribe associated with Kibaki—setting shops and homes aflame. The Mungiki, Kenya’s notorious Kikuyu mafia, retaliated, riots escalating into a rape and murder spree. By midnight, smoke blanketed Kibera, flames licked the sky, and mutilated bodies littered the roads as screams rang out from every corner of the slum....

Prologue

December 30, 2007, Kibera—Leda

NO. PLEASE. PLEASE, world, God, fate, don’t let this happen.

Each man’s hands on Leda’s skin are like desert sand. Hot. Gritty. Rough as splinters of glass.

She ricochets around their circle, a lotto ball in the air mix machine, fate holding its breath. Behind the lunging silhouettes of the men, the slum explodes—fire licking and climbing, spitting at the world. There’s another sound, too, mixed with the whooshing sound of the inferno. Wood, metal, bodies—all crumbling, cracking, hissing and screaming in the flames. It is a symphony of loss.

The men, who are boys really, they yell incomprehensibly, but Leda knows their intentions.

They rip the buttons on her shirt.

They yank the hem of her skirt.

A cloud of reddish dust rises from their feet, as though trying to hide her. But the dust dashes away when Leda is flung to the ground.

For a moment nothing happens.

Then it’s like vampires at the sight of a wound. The men converge—kicking, poking, laughing. They tug at all her protruding parts. Leda’s a centipede in the dust, trying to fold in one hundred legs. Trying to protect the things that matter, things that cannot be undone.

Maybe they will just beat me and go away. This is not my fight. I came to help. Leda wants to shout in their faces. I came to help.

But then she hears it, jumbled with the clatter of their words. Ita. Another one says it. Ita.

So they know who she is.

She is a fish flopping, a tree fallen. A spider in the wind.

She is Ita’s love.

For an instant, Leda thinks it will save her. But as their voices rise, she knows it has doomed her instead.

When the boy drops down on top of her, the force of it is like a metal roof pinning her in a hurricane.

Instantly, all Leda smells is him—sweat and dirt, but rancid, like musk and cheese rusted over with blood. He uses his trunk to flatten her into the ground, his rib bones stabbing into her sternum, her bare skin grinding into the rocks and trash. His legs and hands scramble for Leda’s flailing limbs. The man-boys above laugh and holler.

All she can do is flail and scream.

Leda calls out for the man she loves, the only person who’s ever really loved her.

But it’s the devil who arrives instead.

Ita’s beloved monster, Chege.

Chege’s voice arrives first—a low growl, a familiar snarl. It is the battle cry of an unchained wolf, at home in the darkest of times.

Chege is above her. His dreads close over Leda and her attacker, a curtain of night.

“Help me,” Leda says. Did Ita send him?

As Leda tries to decipher Chege’s spitting words, he yanks the man off and her body takes a breath. The rancid smell, his clawing zipper, the pain in her lungs—it all disappears into the racket above and for one second Leda feels light as a sparrow in the sky. She allows herself to breathe. There is mercy in Chege’s heart after all. He will save her. At least for Ita’s sake.

But then Chege’s eyes flicker, a flap of emotion like blinds shuttering daylight. His hand shoots down and wraps around her throat, a coiling python, and Leda’s breath is lost. His other hand snaps the necklace from her neck. The gold necklace Ita gave her, the sacred chain that is everything to him.

This, Chege knows better than anyone.

He stares at the necklace in his fingers, his eyes bulging, and Leda knows the truth. Chege’s heart isn’t merciful, it’s a furnace of coal that burns only with rage. When both his hands pull Leda up by the throat, the glint of the gold chain taunts her, the shiny sparrow charm a spark in her peripheral vision as the necklace drops to the dirt.

Up, up through the dust, Chege brandishes her like a chunk of meat.

He’s claimed her. Head wolf gets the kill.

His eyes dart about. Leda sees it when he does—a door ajar. He smiles, baring his brown teeth.

Faster than she can scream, Chege kicks her feet to knock her off balance, then drags her across the alley, to the open door. The boys lap at their heels, eyes ravenous. Behind them, the fire rolls atop the mud shacks like a river of exploding stars.

Maybe they will burn for this. Maybe we all will.

Chege yanks her into the dark room, kicks the door shut, and all light goes out in the world.

Chapter 1

November 14, 2007, Topanga, CA—Leda

LEDA SAT IN the sun, feeling judged by the mountains.

Nearby trees wriggled their pom-poms of leaves, but Leda stared far off in the distance, where the scrubby canyon peaks took their turns in the sun and the rain, under the stars and the moon.

Everything in its place.

Except me.

A multicolored mutt entered the patio through a doggie door and hopped onto Leda’s lap. He curled into a furry ball to be petted.

“I quit, Amadeus,” Leda whispered.

The little dog looked up and sniffed.

“I know. Again.” Leda nuzzled the dog’s Mohawk. “Sorry, buddy, no more leftover filet mignon. I told François Vasseur to shove it.”

Amadeus whined.

“Oh please, you won’t starve.” They wouldn’t lose their cozy home in the canyon, either. Leda didn’t have to be a chef, she didn’t have to be anything. Not for money, anyway. But she’d really thought she’d finally found her calling.

Maybe I just don’t have one. A calling. A purpose.

Leda sighed. On a table to her left sat her laptop, waiting smugly for her to start the process again, an all-too-familiar sequence of searching.

Maybe some more iced tea first. Leda went inside, past her bookshelf of cookbooks (culinary school), past the corner display case of cameras (photography school). She bumped the stack of Discover magazines atop the stack of the New Yorkers (double undergraduate majors in science and literature).

When Leda returned with tea, she battled the urge to procrastinate further and pulled the computer into her lap. Mentally, she ran through the various paths she’d tried, weighing them. The thought of starting school again was both exciting and exhausting, but if necessary, so be it. She didn’t want a job, she wanted a career, something she cared about deeply. Something she could throw herself into.

Her fingers hovered, ready to fill the Google search box. She typed in career. Then she added meaningful.

When the search results loaded, she clicked on one after another. Social worker. Counselor. Teacher. An article about a nun in Canada.

The next one was a website listing volunteer opportunities.

Leda inhaled. Why not? She didn’t need the salary, but she felt awful when she wasn’t working. She should leave the paid positions open for people who needed them and help people for free.

Leda sat up straighter in her chair. She scrolled down the listings, each one a short link next to a picture. Teach English as a second language. Tutor troubled teens. Read to senior citizens...

On the third page, Leda saw a link titled Triumph Orphanage, with the tagline We Need Your Help. Next to it was a photograph of a man with a wide, strong, clear face, rich brown skin, and a smile written across like a welcome banner in a crowded airport. Leda leaned forward to stare into the picture. She clicked on the link and it opened a new page, with the picture enlarged within. The man’s smile held no trace of mental chatter or self-consciousness behind it. It was free and complete, open. Leda felt a surging desire to touch it, the smile, an entirely unfamiliar urge.

Below the handsome man’s picture was a snapshot of seven schoolchildren in an orphanage, smiling ear to ear. Leda looked closer at the photo, at the background. She scrolled down to the text. The man who ran the orphanage funded it by guiding safari tours—

Whoa. The orphanage was in Africa. In Kenya. In a slum called Kibera, outside Nairobi.

Leda exhaled and clicked the back button. No way. Let’s not get crazy, thought the woman who got anxiety in crowded grocery stores. Leda looked down at Amadeus, then inside to her cozy little house, each piece of furniture and decoration meticulously chosen and arranged.

No way could she do something like that.

Automatically, she fingered her burn scar, the patch of skin near her jaw, so smooth and soft, it was like a stone in the ocean’s break. She shut her eyes, felt her heart begin to race, heard the song humming the start of an awful memory.

When the phone rang, Leda nearly fell off her chair from startling.

She grabbed her phone from the table. Estella.

She hadn’t spoken to her mother in months.

“Leda?” came the raspy voice on the other end of the line.

“Hello, Mother. Something wrong?”

There was a pause. Leda sank into her chair.

“You’re the one who sounds like something’s wrong.” She sighed. “What is it?”

Leda frowned. Estella would get it out of her eventually. “I quit my job.”

“Surprise, surprise. What was wrong with this one?”

Leda’s teeth gritted together. Invisible armor clinked into place. “It was a sweatshop. My boss was abusive. But mainly it just wasn’t what I thought it would be.” Leda looked up. The mountain was still staring at her. She averted her eyes. “I wanted to find something meaningful to do with my life.”

As soon as she said it, she regretted it. Naked emotion was nothing but ammunition for Estella.

Sure enough, Estella “hmphed” loudly. “Not sure you’re the charitable type, dear.”

Leda thought of the photo of the man with the smile. “Actually, I was just looking at a posting to volunteer in Kenya.”

Estella’s cackling laugh poured into Leda’s ear like a bucket of wriggling maggots. “Leda, you are, what, thirty-two? Isn’t that a little old to play the college kid off to save Africa?”

Choice words died on Leda’s tongue. “Was there something else you called about, Mother?”

Estella’s cackle snuffed short. A pause. “No. I think that’s enough for today.”

Leda listened to the call disconnect, her eyebrows knitted together. When she set the phone back on the table, she saw that her hands were shaking.

The laptop’s face was in sleep mode. Leda swiped her finger across the mouse pad and the screen jumped back into view.

The picture was waiting.

She read the caption beneath the smile. His name was Ita, the man who ran the orphanage.

Ita, with a gaze fair and bright, surrounded by smiling children.

College kid, indeed.

Leda opened a new tab. Travelocity.

Chapter 2

December 9, 2007, Kibera—Leda

WHEN LEDA LOOKED out over Kibera for the first time, she thought of the sea behind her mother’s house, how it unfolded into infinity, unfathomable and chilling even on a sunny day. Leda stumbled at the top of the embankment, grabbed for the handle of her suitcase and stood tight until the rushing realization of smallness receded from her knees.

One million people, her guidebook claimed, crammed into a labyrinth of mud and metal shacks. It was a maze to make Daedalus proud. No Minotaur could escape from here. The slum was the Minotaur, gorging itself on fleeting youth and broken dreams.

Leda felt the dampness of her washed hair morph into sweat. She’d arrived the night before, had been ushered quickly into a cab and sped to her shiny white room at the Intercontinental in Nairobi. But now she stood on the edge of Nairobi’s secret, two terse sentences in the hotel’s welcome binder—the Kibera slum. Bounded by a golf course, towering suburban gates, a river, a railroad and a dam. Cordoned off. Now Leda saw what that meant—a place with no running water, no electricity, no sanitation system—the blank spot on the map of the city, officially unrecognized. A space smaller than her Topanga Canyon neighborhood, but thirty times the population density of New York City.

From where Leda stood, Kibera below was an undulating sea of rusted rooftops, ending at the horizon and the glaring morning sun.

Samuel, the guide Leda had hired to take her on a tour of Kibera and to the orphanage, stood likewise frozen, but unalarmed. More than likely he was used to the tourist gasp, had it penciled into his schedule.

Leda looked at him sideways, her eyes grabbing on to him like a buoy at high sea. Samuel was younger than her for sure, no more than twenty-five, but taller by a foot. His face was smooth, shiny in the heat. How did he feel? Awkward, as she did, embarrassed? Was he secretly seething?

Normally, Leda was good at discerning people’s thoughts and moods, a skill learned early in her mother’s house. It wasn’t a talent that brought her any closer to people, however.

She closed her eyes to the miles of dirt and metal, shut her ears to the clanging roar before them and the gridlocked traffic behind them, and tried to sense any irritation or ill will coming from Samuel. But his stretched posture and his even stare gave nothing away. If nothing else, he seemed dutiful. This was another Sunday, another customer.

Samuel sensed Leda’s searching, as people always did, and he turned. “Do you want to take a picture?”

Leda’s hand went into her pocket, wrapped around her camera. Right. A photographer should want to take a picture. But when she saw the men down the embankment staring, her hand let go of the camera. These were the kinds of moments that confirmed for Leda she wasn’t cut out to be a photojournalist.

“It’s okay. Let’s just go,” she said.

Samuel nodded and stepped behind Leda to pick up her sixty-pound suitcase. He hoisted it onto his back heavily, as though it was a piano, and started down the dirt hill.

The sight gave Leda a queasy jolt. “Wait. There’s no road?”

She’d looked at the pictures online, she’d seen the narrow alleys. But she’d also assumed there would be a way in, a way out. A road.

Samuel turned. He smiled.

Leda felt the sneer behind his smile. She looked down, her cheeks burning. She studied the orange dust under her boots. The color was due to the dearth of vegetation, she’d read. The iron turned the clay minerals orange.

Samuel was off and walking. Leda scrambled after him down the hill, feeling like a clown fish in a pond. She watched him start across a rickety footbridge arched over a brown swamp of trash, with sugarcane growing in thick clumps through the waste. Children waded in near the cane.

Leda followed, studying her shoes to avoid all the eyes on her.

The other side of the bridge landed Leda in a landscape that was more landfill than ground, and she nearly went down on the twisted path of plastic bags. She was grateful for her tennis shoes, but still furious at herself for the suitcase. Imagine if she’d brought her second one, instead of leaving it with the hotel. Underneath the ridiculous load, all she could see were Samuel’s sandals traversing the winding path over rock and drainage creeks. And all she could do was follow along, like a princess after a porter, trying not to trip. Her mother’s words blared in her head. Off to save Africa?

As doubt clogged her throat, Leda felt sure she would drown in the smell. Moldy cabbage, rotten fish, cooking smoke, but mostly it was the steaming scent of human waste that poured into Leda’s nose and mouth, saturating her as if she could never be free of that smell again. She opened her mouth to breathe, and gagged on the sweat that dribbled in.

Now the view of the slum had disappeared and they were inside it, weaving through narrow spaces and crisscrossed paths like an ant farm in hyperdrive.

Men with hollowed cheeks and yellowed eyes stared at Leda. Women—in the midst of tending children and selling and trading and gossiping and cooking and cleaning—their eyes flickered warily as she passed.

The children, however, were a different story. Schoolkids flew up around Leda like clouds of sparrows, waving their arms and chirping Howareyou? Howareyou?

Leda was grateful to them for their acceptance and she answered with the Swahili words she’d only ever spoken to her iPod. “Jambo,” she said, and they giggled.

“Present,” one boy shouted amiably.

Samuel stopped suddenly, and motioned for Leda to stand beside him. He shooed away the children, not meanly but firmly, and set down the suitcase, ready, Leda supposed, to continue with the tour he’d begun when they met that morning in the café in Nairobi.

“So, you are here to volunteer. What is it you do in America? Are you a teacher?”

Avoiding his question, Leda looked away. “Yes, I’m a volunteer. Here to help.”

Samuel nodded. “Do not give the children money. They do not understand it. In your country maybe you are a poor teacher, but here your money is a lot. This puts ideas in the children’s heads.”

Leda looked into Samuel’s face, at the sheets of sweat soaking his T-shirt. She moved closer and released the handle on the suitcase, demonstrating that she would pull it.

Samuel smiled again, the smile Leda hated and that she felt hated her. She nodded toward the children playing nearby. “What ideas?”

“The idea that begging is a job. Or that robbing you would not be so bad since you give it so easily.”

Samuel took a breath and walked a few steps. Now he resumed his script as he pointed here and there. “When the British left, they gave this land to the Nubians—Muslim Sudanese soldiers. But with no deeds. The Nubians became illegal landlords and the seeds of war were planted in this dirt. Muslim against Christian. Kikuyu against Luo. There have been many problems.”

“But then, technically, the government owns the land? They could help.”

They passed a beauty salon of women who stared at Leda struggling to wheel her suitcase through the trash. Samuel waited. Silently, he watched the trash pool around the suitcase wheels until Leda found herself dragging, not wheeling, the suitcase. His look more or less said I told you so.

“Yes, they could help,” Samuel said. “But it is more convenient for them to do nothing. As long as the slum is illegal, they do not have to provide what the city people have rights to.”

A man tripped over Leda then, for cosmic emphasis, sloshing water from a yellow jug. The dirt beneath her shoes turned to mud and the man looked at it and frowned. Leda’s skin burned under the man’s indignation. He huffed and walked on. How far had the man walked for that water? “Then how do they get the necessities?”

“Everything is for sale in Kibera. Water. Use of the latrine. A shower. People pay the person who steals electricity for them. They pay the watchmen, really paying them not to rob them. They pay thieves to steal back what other thieves stole in the night. Women who sell changaa, they pay the police a bribe. Women who sell themselves, they pay the bribes with their bodies. But still one must pay for charcoal and food and school. The hardest thing to justify is school.”

“How do people pay for everything?”

“They don’t.” Samuel pointed at the ground.

Leda lifted her right foot and a sticky plastic bag dangled from it in the dusty air. She considered anew the blanket of trash bags.

“When you can’t pay or it’s unsafe to go, then you do your business in a bag and—” Samuel’s hand carved an arc through the air that ended at her shoe. “Flying toilets.” He took the suitcase, now soiled from her dragging it through the refuse.

“We’re almost there.” He pointed ahead.

Leda was in shock. But before they moved on, she had to ask a question she thought she knew the answer to. “Do you live in Kibera, Samuel?”

It was the first time emotion crossed his face unfettered. “Yes,” he said, and heaved the suitcase onto his back as he turned away, a turtle putting his shell back on.

Leda followed him deeper into the slum, supplementing his practiced explanations about Kibera with the rushing things her eyes and ears told her. Kibera was an assault of objects, colors, smells and sounds, all suddenly appearing out of the dust inches from her face. As they ducked between mud/stick structures, colored laundry fluttered and dripped overhead. A volley of muffled chatter and music echoed from all directions.

Leda wondered what privacy meant in Kibera, if anything. How would any one of these people feel if they found themselves alone in a quiet house like the one she shared with Amadeus? Or in a mansion of marble, glass and sky, like her mother’s? So much space all to themselves.