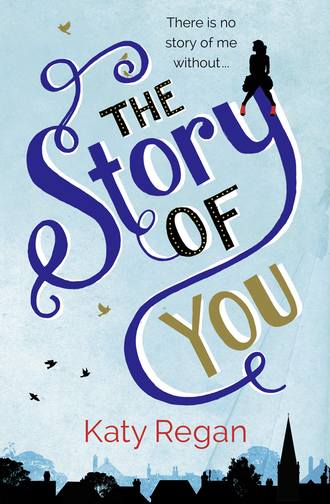

The Story of You

Полная версия

The Story of You

Жанр: периодические изданиясовременная зарубежная литературасборникипублицистика и периодические издания

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2018

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу