Полная версия

The Quality of Mercy

The Quality of Mercy

Faye Kellerman

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in the United States by William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers, 1989

This ebook edition published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Plot Line, Inc. 1989

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photography © Shutterstock.com

Faye Kellerman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © April 2019 ISBN: 9780008293543

Version: 2018-12-12

Dedication

For Jonathan.

And for Barney Karpfinger: Diogenes,

stop looking, I found him.

Thanking the translators: Maribel Romero,

Phyllis Elliott, and Miriam Lewis.

And a special thanks to John and Mary Jane Hertz—

two people worthy of their titles.

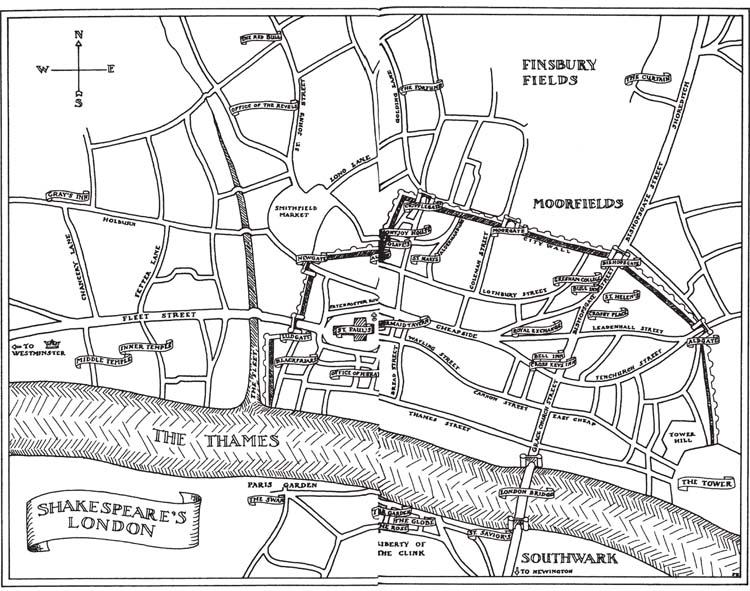

Map

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Lisbon, 1540

Chapter 1

London, 1593

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Historical Summary

Keep Reading

About the Author

Faye Kellerman booklist

About the Publisher

Chapter 1

As I see the first hint of sunlight, the death march begins. We advance toward the Terriero do Paco—the great city square adjacent to the Royal Palace on the seafront.

Leading the processional is Don Henrique—the Inquisitor General of Portugal by appointment of his older brother, His Royal Highness John the Third. Don Henrique is an ugly man—lean, with an avian nose, and black eyes set so deeply that the sockets appear hollow. His thick beard—a weave of bronze, copper, and iron—is meticulously shaped to a dagger point. His dress is appropriately august—official: floor-length black robe and cape, white clerical collar, and black trapezoidal hat. Dangling from his neck is his scallop-edged crucifix of gold, inset with topaz, lapis, aquamarine, sapphire, and topped with a finial of diamonds. A haughty man, Don Henrique always wears jeweled crosses. Gilt bible clutched to his breast, eyes fixed straight ahead, he presses on slowly but inexorably, prepared to carry out the work of his God.

Following the Inquisitor are four rows of black-garbed monks. Around their necks are unadorned crucifixes fashioned from the heavier base metals. Rigid and stone-faced, they carry black-covered bibles and hold aloft crosses and banners. They chant low-pitched dirges as they trudge forward on sandaled feet.

Behind the clergy are the royal officials and the black-hooded executioners—the secular arm of the law. Their ranks advance in taut, military fashion—arms swinging with pendular precision, not a boot out of step.

We are at the rear of the retinue. The victims—the wretches. We are heavily guarded and hold lighted tapers that spit fire into the early morning sky. Some of us endure the ordeal with stoicism—posture erect, gait sure-footed and strong. That is how I walk. Others about me seem stuporous, stumbling off-balance, as if being yanked forward by an invisible harness. The weakest weep openly.

The auto-da-fé—act of faith—is the day of reckoning for us. We’ve been convicted of violations of the Church. We walk forward, clearly identified for the onlookers; we wear the dreaded sambenito—the two-sided apron of shame imprinted with symbols corresponding to our infractions. Serious sinners like myself wear corazas—conical miters—as well.

Some are considered penitent and deemed reconcilable to the Church. They will gratefully accept the penalties meted out to them. The pettiest among them will be punished with fines, terms of forced servitude, or imprisonment. More serious transgressors will merit whipping or public shaming—being stripped to the waist and paraded around town to the derision and jeers of their countrymen. Wretches who committed grave infractions will be plunged into poverty, have all their worldly possessions confiscated by the Holy Office. These offenders will be stigmatized for generations, their descendants barred forever from entering the Holy Office, from becoming physicians, tutors, apothecaries, advocates, scriveners, or farmers for revenue. They will be forbidden to dress in cloth woven from gold or silver thread, wear jewelry, or ride on horseback.

But they are fortunate.

I, and others like me, are deemed impenitent. We hapless souls are guilty of the most odious heresies. My specific crime is Judaizing—practicing and professing the ancient laws of Moses rendered obsolete by their Jesus Christ. Once, Spain called me a converso—a Christian of Jewish bloodline. I was an overt Catholic, but secretly I practiced the old ways. My transgressions were discovered by a wanton woman. Now I am doomed.

Distinguished from the fortunates by our green tapers and dress, we—the relapsos—wear special fiery miters and the sambenito of death imprinted with the likeness of the Devil himself. Around his horned visage and pronged fork are leaping flames: the Hell that is to await us.

I spit on their stinking Christian ground. That’s what I think of their Hell.

This morning will be my last. Before the night is over, I will be sentenced to die without effusion of blood, their castigation derived from John 15:6—from the teachings of their Savior Himself: If a man abide not in me, he is cast forth as a branch and is withered and men gather them and cast them into the fire, and they are burned.

The dank ocean fog begins to melt, yielding to an opaline sky dotted with tufts of woolly cloud. At six in the morning the city bells ring out the signal and I shudder with dread. The cobblestone walkways begin to fill with austere gentlemen somberly wrapped in dark capes. They step with much haste, their servants at their heels. Ten minutes later the veiled women of the households emerge—wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters. Some of the women hold babies and toddlers, others drag older children, chiding them for slowness. The streets soon become a throng of bodies. In the center is this murderous tribunal—as poisonous as an asp. It undulates its way to the city square.

By the time the officials arrive at the Terreiro, most of the spectators have been positioned, either standing, or seated in the gallery benches that form a semicircle around the dais, the garrotes, and the stakes. In the foreground are the white-capped swells of the ocean. In the background stands the great palace, casting a deep shadow over the galleries.

We are ordered to stand up straight. A guard hits the woman next to me. She is eight months pregnant, younger than I, I think. Around seventeen. Her back is stooped from the weight of her fruit. I smile at her. Wet-eyed, she smiles back at me. Our eyes have told each to be strong.

As Don Henrique ascends to the black-draped podium, the noise of idle conversation softens, then finally quiets to silence. The Inquisitor stands immobile, his head bowed in meditation. The sun, now higher in the advanced morning sky, projects a metallic sheen onto the ground, gilding the Inquisitor. Tides yawn rhythmic, lazy growls. An uneasy calm has blanketed the air.

Suddenly, a mourner’s wail blasts through the square, reverberating against salty air and harmonizing with the ocean’s roar—the baritone summons of a sheep’s horn. The pregnant girl next to me jumps. I do nothing. The audience is cleaved in two by a red carpet, unfurled and smoothed by royal attendants.

King John and Queen Catalina—may they rot in Hell—enter the gathering, followed by their entourage. His Majesty’s porcine features are embedded in pillowy cheeks that are pink and pockmarked. He’s fair-complexioned, with a neatly trimmed but scant beard. His portly frame looks especially obese today, swaddled under layers of clothing. His sable collar, draped over a padded doublet of gold, frames his chin like the mane of a lion. Resting on his shoulders is a blue velvet robe secured by a clasp of jewel-encrusted animals linked together with braided silver. His round hose are pleats of blue and scarlet velvet and puffed out at the hip line. Hanging from his belt is a gold scabbard revealing the gem-studded handle of a broadsword. His stockings, no doubt made of pure silk, are obscured by high-polished black boots that end mid-thigh. On his head is perched the royal crown of the State.

The Queen is the daughter of the Emperor Charles the Fifth of Rome, granddaughter of Ferdinand and Isabella. Her facial features are small and pinched, her complexion tinged with olive. Her slender arms are hidden under full, maroon sleeves, but the bodice and stomacher of her dress reveal her pride, her vanity—a tiny waist that is rumored to be encircled easily by her husband’s thick hands. She wears a flowing skirt of black taffety overlaid with gold lace, and is crowned with a diamond and emerald tiara. A staunch Catholic, Catalina is the driving wind behind the Inquisition. She was inspired by the religious fervor of her late confessor, Frai Diogo da Silva—another pig.

The monarchs are led to raised thrones at the top of the galleries. As soon as they are seated, the Inquisitor lifts his head and extends his arms toward the rulers of the land.

“Mighty Sovereigns.” Don Henrique bows low. “King and Queen, Protectors of the True Faith. On a throne of velvet you sit most high. Justice and truth in God you preach as well as practice. In the great reign of King John the Third, the Savior shall once again witness purity of blood as we ferret out the foul stench that has infiltrated the rightful Church. Only under fair and impartial rulers such as yourselves, good King and Queen, will Catholicism be purified for true believers. A pure race—of pure, true Christians—to serve the most Holy One, Jesus Christ, the embodiment of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.”

King John and Queen Catalina—the swine—duly nod.

“As for the condemned, the wretched souls,” Don Henrique continues, “assuming they have souls, so beastly and dung-riddled are their filthy, ghastly undertakings …”

The crowd nods in agreement. A baby lets out a sudden shriek.

“Yea,” Henrique exclaims. “Yea … even an innocent babe cries out at the sight of the Devil himself, beseeching the Lord, ‘Most holy Savior! Protect my baptized soul!’”

The Inquisitor’s voice rings out. “Protect me against the disgusting, putrid pollution that has entered the most holy religion of God, subverting the good into evil.”

Don Henrique points to us—those sentenced to death.

“Damned ye be! Damnable are your crimes against man and against God. Ye are to consider the stake a most gentle taste of what awaits you once ye are in the grasp of the Devil. Ye shall drink boiling lead and eat molten brimstone for ale and food. Daily ye shall be skinned and burned, steamed in cauldrons of liquid fire. Your livers shall be fodder for the vulture, your hearts sustenance for the crow. Your entrails shall ye eat, the filth of your bowels shall ye breathe. Your eyes will be plucked out with glowing pokers as the Devil and his servants laugh at your wretched miseries.”

The Inquisitor holds his breath until his face is flushed, then lets out a chilling scream directed at the crowd.

“Ye think you are safe from the wiles of the Devil? Think again lest in your airs ye drop your shields and give space for the Devil to come and do his bidding.”

He returns his attention to us. I listen, but his words do not affect me. I’ve heard them many times before. Don Henrique clutches his heart and says,

“Satan—cursed be his name—has entered these filthy souls. But Jesus Christ, in His martyrdom, died for you. Died for your souls—all souls, the filthy with the pure. There remains hope for your souls in the life hereafter. Your earthly life is over. By your own stinking hand ye were sentenced, as God and the Church had tried to enter in life and failed. Perhaps ye shall see His wisdom now that death is upon your wretched bodies.

“Ye still have a chance! Ye still can make restitution to the cross by publicly confessing your errors and admitting them before man as well as God.”

Don Henrique lights a torch and hoists it into the air.

“Let the proceedings begin,” he says.

The ordeal will last all day. The lightest offenders are dealt with first. One by one they are summoned before the Inquisitor, insulted and cursed, then assigned their punishment by the secular arm. Maria Gomez is fined for appearing unveiled in public against the wishes of her husband. Joao Dias is whipped for theft. Salvador Guterrias is imprisoned for life for unnatural fornication with his wife. They should know the real truth. In the dungeon he told me that he had fornicated with animals, that they were more satisfying to him than his fat, stinking wife. Had that bit of knowledge come to the attention of the Inquisition, he would have been sentenced to die.

Name after name is called. We are forced to stand rigid during the proceedings. I worry about the girl next to me. I fear she will faint and then the guards will beat her. But she proves stronger than I had first thought. Yes, she sways on her feet, but her spine remains upright.

The tribunal continues past the noon hour and chews up the afternoon until dusk spreads over the square. No conversation in the audience is permitted. Children who violate the rule are immediately silenced—first verbally, then with a sharp slap. Roving guards maintain decorum with stern demeanors and, for those who have succumbed to dozing, a rap on the head with a stout staff.

Nightfall begins to darken the landscape, but the Inquisitor shows no signs of tiring. Do murderers ever tire of their lust for blood? As the torches are lit around the edges of the stage, Don Henrique points an accusing finger at the first of us condemned to death.

“Fernando Lopes!” he cries out. “Come forward.”

Lopes is an emaciated, hirsute man of thirty. His pale skin stretches over a large bony frame that once had been thick and muscular. I had known him before he was caught. He has degenerated very badly. His eyes, dulled by years of incarceration, seem mad now. They dart about aimlessly. His beard, once dark and handsome, is a gray nest of brambles, caked with spittle and blood. His hands are bound with leather straps, but his feet are untethered and bare. He is pulled forward by two guards.

“Thou miserable, filthy wretch of dung!” the Inquisitor says. “Thou hast been accused of relapsing!”

“No,” Lopes protests.

It is useless to deny, but Lopes will do it anyway. He is that kind of man.

“Quiet, sinner!” shouts the Inquisitor. “Thou knowest this to be truth! Thine own daughter confessed thy sins. Because her confessions were made under oath to the Holy Office, her life shall be mercifully spared. But thee … thou who wast warned in good faith—”

“But I have done nothing, Most Holy—”

“Still thou deniest what has been observed and verified by thine own daughter!” the Inquisitor screams. “Thou art to be eternally damned if thy confessions are not made before thy death. Make thy confessions, sinner!”

“But I have done nothing—”

Don Henrique addresses the audience, his expression incredulous. “What is to be done with this mongrel to save his soul? Must we show him the Devil’s way?”

Turning to one of the sentries, he orders, “Shave this New Christian!”

As two warders restrain Lopes, a third takes his torch and brings it to the struggling man’s beard. The whiskers catch fire and Lopes screams. I cannot watch anymore.

Henrique says, “Confess thy sins, wretched soul, and allow the Savior to take pity on you!”

“I confess! I confess!”

“Thou will confess in earnest?”

“Yes, yes, only please! …”

I force myself to glance at the wretched man. Lopes is on fire—a human torch. His shrieks curdle my blood.

“Douse the fire,” Don Henrique suddenly commands.

A bucket of water is splashed into Lopes’s face. He gasps for air, his face a grotesque melting candle of dripping water, burnt hair, and charred skin.

The Inquisitor accuses, “Thou changest linens on Friday. And thou concealest the treacherous act from thy servants by placing the dirty linens atop the clean, only to remove them before sunset on Friday. Admit it!”

Lopes says nothing.

“Still thou wadest in defiance!”

“No, Your Holiness,” Lopes squeaks.

“Speak up, Fernando Lopes!” the Inquisitor thunders. “Did thou change linens on Friday?”

Lopes nods.

“Dost thou admit to thy sin?’

“Yes, Your—” Lopes swallows. “Yes, Your Holiness.”

“And to thy sin of refraining from the consumption of pork?”

“But Your Holiness,” Lopes protests feebly, “pork makes me ill—”

“Still thou retainest the Devil’s obstinence?”

“Truly my stomach is ill-bred for its consumption.”

Don Henrique turns to the galleries.

“Must we continue listening to the lies of this filthy Jew? Must we prove our intent to save his soul once again? Light the beard.”

“No!” Lopes screams. “Yes, I confess. I did abstain from the consumption of pork.”

“Thou art a Judaizer. Admit it, Jew!”

“Yes, yes, it is true!”

“And who else was involved in thy crimes? Thy wife?”

“No! Verily, she is an honest Christian!”

“As thou art an honest Christian,” Don Henrique mocks.

“No, no! She knows nothing of my sins—”

“Admit it, dog! Thy wife is also a sinner—”

“But it is not true!”

“Light his beard.”

“No,” Lopes pleads with anguish. But this time he refuses to speak further. His cries are put to rest when again Don Henrique orders his beard to be drenched.

“Fernando Lopes,” says the Inquisitor, “dost thou repent for thy wicked ways?”

“Yes,” Lopes whispers.

“Dost thou embrace the cross and pledge an oath of faith that Jesus Christ is thine only chance for salvation in the Hereafter?”

“Yes.”

Don Henrique walks over to the condemned man and holds out his crucifix.

“Embrace the cross, Fernando.”

Lopes does as ordered.

“Pledge thy faith to Christ the Lord,” demands the Inquisitor.

“I pledge my faith to Christ the Lord.”

“That He is thy Savior.”

“He is my Savior.”

“And thy salvation in the Hereafter.”

“And my salvation in the Hereafter.”

“Thou art a wretched sinner, but thou dost make penitence on this day for all thy previous sins.”

“I am a wretched sinner, but I do make penitence on this day for all my previous sins.”

“And pray for the mercy of Christ.”

“And pray for the mercy of Christ.”

“In nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti.”

“In nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti.”

“Fernando Lopes,” cries the Inquisitor, “for thy free confessions, thou warrant mercy. Thou shalt be relaxed to the secular arm for punishment, but shalt be garroted in a swift manner as a reward for thy free confessions and thy pledge of oath to the True Faith.”

The guards unbound the prisoner’s limbs and lead the limp, burnt man over to an open iron collar attached perpendicularly to a metal post. As the collar is clamped shut around his scrawny neck, Lopes begs for his life, but his whines are cut short at the first turn of the screw.

The collar tightens. Lopes gasps and clutches at the metal band constricting his throat.

The screw is turned again.

Lopes’s pasty face takes on the blue tinge of strangulation.

The screw makes a final revolution, and Lopes’s arms, legs, and bowels relax.

The crowd roars at the sight of the lifeless body.

A few minutes later a warder loosens the screw and removes the collar. Lopes tumbles to the ground, a pile of dead bone and skin. The body is dragged by the hair to a pyre. After securing the corpse to the stake, the sentry notices that the head is dangling precariously from its broken neck. He grabs a handful of Lopes’s hair and ties it around the stake. The head is now sufficiently upright, dead eyes gaping at the galleries. Satisfied, the sentry walks away to join his ranks.