Полная версия

Stephen Fry in America

‘Hey, you know, I don’t live and die just for Republicans or just for whacking down Democrats, I wanna get America right,’ says Mitt when invited to blame the opposition.

A minder makes an almost indiscernible gesture from the back, which Mitt picks up on right away. Time to leave.

‘Holy cow, I have just loved talking to you folks,’ he says, pausing on the way out to be photographed. ‘This is what democracy means.’

‘I told you he was awesome,’ says Deirdra.

In the afternoon we move on to Phillips Exeter Academy, one of the most famous, exclusive and prestigious private schools in the land, the ‘Eton of America’ that educated Daniel Webster, Gore Vidal, John Irving, and numerous other illustrious Americans all the way up to Mark Zuckerberg, the creator of Facebook as well as half the line-up of indie rockers Arcade Fire. The school has an endowment of one billion dollars.

In this heady atmosphere of privilege, wealth, tradition and youthful glamour Mitt is given a harder time. The students question the honesty of his newly acquired anti-gay, anti-abortion ‘values’. It seems he was a liberal as Governor of Massachusetts and has now had to add a little red meat and iron to his policies in order to placate the more right-wing members of his party. The girls and boys of the school (whose Democratic Club is more than twice the size of its Republican, I am told) are unconvinced by the Governor’s wriggling and squirming on this issue and he only just manages, in the opinion of this observer at least, to get away with not being jeered. I could quite understand his shouting out, ‘What the hell you rich kids think you know about families beats the crap out of me’, but he did not, which is good for his campaign but a pity for those of us who like a little theatre in our politics.

By the time he appeared on the steps outside the school hall to answer some press questions I was tired, even if he was not. The scene could not have been more delightful, a late-afternoon sun setting the bright autumnal leaves on fire; smooth, noble and well-maintained collegiate architecture and lawns and American politics alive and in fine health. I came away admiring Governor Romney’s stamina, calm and good humour. If every candidate has to go through such slog and grind day after day after day, merely to win the right finally to move forward and really campaign, then one can at least guarantee that the Leader of the Free World, whoever he or she may be, has energy, an even temper and great stores of endurance. I noticed that the Governor’s jacket had somehow magically been placed in the back of his SUV. Ready to be put on in order to be taken off again next time.

Bretton Woods

New Hampshire is more than just a political Petri dish, however; it is also home to some of the most beautiful scenery in America. The White Mountains are a craggy range that form part of the great Appalachian chain that sweeps down from Canada to Alabama, reaching their peak at Mount Washington, the highest point in America east of the Mississippi, at whose foothills sprawls the enormous Mount Washington Hotel at Bretton Woods. Damn – politics again.

I never studied economics at school and for some reason I had always thought that the ‘Bretton Woods Agreement’ was, like the Hoare – Laval pact, the product of two people, one called Bretton and one called Woods. No, the system that gave the world the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and stable exchange rates based on a decided value for gold was the result of a conference in 1944 here in Bretton Woods, attended by all the allied and non-aligned nations who knew that the post-war world would have to be reconstructed and developed within permanent and powerful institutions. The economic structure of the world since, for good and ill, has largely flowed from that momentous meeting – if structures can be said to flow.

The hotel is certainly big enough to house such a giant convention. It is hard not to think of Jack Nicholson and The Shining as I get repeatedly lost in its vast corridors and verandas. I sip tea and watch the huge vista of a misty, drizzly afternoon on the mountains recede into a dull evening. If fate is kind to me, the next day will dawn bright and sunny. Perfect for an expedition to the summit. Unlikely, for Mount Washington sees the least sunshine and the worst weather of anywhere in America. That is an official fact.

Fate is immensely kind, however. Not only does she send a day as sparklingly clear as any I have seen, but she also makes sure that the train and cog line are in prime working order so I can make my way up the 6,000 feet in comfort and without the expenditure of a single calorie, all of which – thanks to my American diet – have far too much to do swelling my tummy to be bothered with exercise. A steam locomotive – nuzzle pointing cutely down ready to push us all up the hill – puffs gently at the foothills. This rack and pinion line has been taking tourists and skiers to the top of Mount Washington for over a hundred and forty years. I join a happy crowd of people on board. The ‘engineer’ (which is American for engine driver) does something clever with levers at the back of the train and after enough clanking and grinding we are off. Up front, the grimy-faced brakeman tells me a little about the locomotive.

‘This was the first,’ he says proudly.

‘What the first in the world?’

‘Yep.’

It wasn’t actually, but I haven’t the heart to tell him. The world’s first cog railway was in Leeds, England, but the Mount Washington line was the first ever to go up a mountain, and that’s what counts.

Up we go, pushed by the engine at no more than a fast walking pace. You can almost hear the locomotive wheeze ‘gonnamakeit, gonnamakeit, gonnamakeit!’ And make it we do.

New Hampshire? The highest point in Old Hampshire that I have ever visited is Watership Down, a round green hillock famous for its bunny rabbits. The great granite crags of the White Mountains are a world away from the soft chalk downs of the mother country. The sheer scale is dizzying. I feel as if I have visited two huge countries already and all I have done is take a look round a couple of America’s smaller states.

The Appalachians and I have a long way still to go before we reach the south. I gaze down as they march off out of view. What a monumentally, outrageously, heart-stoppingly beautiful country this is. And how frighteningly big.

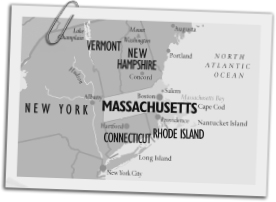

MASSACHUSETTS

KEY FACTS

Abbreviation:

MA

Nickname:

The Bay State

Capital:

Boston

Flower:

Mayflower

Tree:

American elm

Bird:

Chickadee

Motto:

Ense petit placidam sub libertate quietem (‘By the sword she seeks peace under liberty’)

Well-known residents and natives:

Paul Revere, John Adams (2nd President), John Quincy Adams (6th), Calvin Coolidge (30th), John F. Kennedy (35th), George H.W. Bush (41st), John Hancock, Benjamin Franklin, Susan B. Anthony, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Robert Kennedy, Edward Kennedy, Michael Dukakis, John Kerry, Mitt Romney, John Harvard, Eli Whitney, Elias Howe, Samuel Morse, Alexander Graham Bell, James McNeill Whistler.

MASSACHUSETTS

‘By twelve o’clock it’s all over and everyone is in bed. There’s more true Gothic horror in a digestive biscuit, but never mind.’

Massachusetts prides herself on being a commonwealth rather than a state. It is a meaningless distinction constitutionally but says something about the history and special grandeur of this, the most populous of the New England states. Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, the Kennedys, Harvard University, Boston … there is a sophisticated patina, a ritzy finish to the place. It has its blue-collar Irish, its rural poor but the image is still that of patrician wealth and founding history. And a quick glance up at the list of notable natives shows that American literature in the first two hundred years of the nation would not have amounted to much without Massachusetts. Maybe having to learn how to spell the name of the state inculcated a literary precision early on …

Whaling

Much of the prosperity of nineteenth-century Massachusetts derived from the now disgraced industry of whaling. The centre of this grisly trade was the island town of Nantucket, now a neat and pretty, if somewhat sterile, heritage and holiday resort. It is a pompous and priggish error to judge our ancestors according to our own particular and temporary moral codes, but nonetheless it is hard to understand how once we slaughtered so many whales with so little compunction.

I am shown round the whaling museum by Nathaniel Philbrick, the leading historian of the area, a man boundlessly enthusiastic about all things Nantuckian.

‘The whaling companies were the BPs and Mobils of their day,’ he says as we pass an enormous whale skeleton. ‘The oil from sperm whales lit the lamps of the western world and lubricated the moving parts of industry.’

‘But it was such a slaughter …’

Nathaniel hears this every day. ‘Can’t deny it. But look what we’re doing now in order to get today’s equivalent. Petroleum.’

‘Yes, but …’

‘The Nantucket whalers depredated one species for its oil, which I don’t defend, but we tear the whole earth to pieces, endangering hundreds of thousands of species. We fill the air with a climate-changing pollution that threatens all life, including all whales.’

The awful devastation to the whale on the one hand and the unquestionable courage, endurance and skill displayed by the whalers on the other has been Nathaniel’s theme as a writer for many years now.

‘How will our descendants look at us?’ he wonders, as we look down on Nantucket from the roof of the museum. ‘Only a sanctimonious fool could deny the valour and hardiness of the New England whalers. But will our great-grandchildren say the same about the oil explorers and oil-tanker crews?’

A petroleum-burning ferry takes us away from Nantucket, past Hyannisport, the home to this day of the Kennedy compound: ‘Yeah, saw old Ted sailing just yesterday afternoon,’ the ferry captain tells me. ‘Gave me a wave, he did.’

The Pilgrims

I drive along the coast to Plymouth, Massachusetts where they keep a replica of the Mayflower, the ship that carried a boatload of Puritans from Plymouth, Devon to the coast of America in 1620–21. These Pilgrim Fathers have been given, almost arbitrarily one might think, the iconic status of nation-builders; it is almost as if Plymouth Rock is the very rock on which America itself was built. The turkeys those pilgrims killed for food and the sour cranberries they ate with them in their first hard winter are annually memorialised on the third Thursday of every November in the great American feasting ritual known as Thanksgiving. Those who can trace their ancestry back to the pilgrims count themselves almost a kind of aristocracy.

I enjoy a morning clambering about the boat listening to the heritage talk and watching parties of American schoolchildren having the legend of the Pilgrim Fathers reinforced in their young minds.

‘I be John Harcourt, out of Plymouth, Hampshire,’ declaims a bearded man in a leather jerkin.

‘No you baint,’ I tell him firmly. ‘You be an actor, out of New York City.’

Only I say no such thing because I am too polite. The ship is crewed by Equity members in smocks and leather caps whose idea of an English accent is to say ‘thee’, ‘thou’ and ‘my lady’ and trust to luck.

‘Do thee hail from the Old Country?’ I am asked.

‘No, no, no!’ I am once more too polite to say. ‘You mean “Dost thou” – “Do thee” makes no sense.’

The idea that the Puritans came to New England to avoid persecution is lodged firmly in the American psyche. Gore Vidal’s view that they came, ‘not to be free from persecution, but on the contrary, to be free to persecute’ while heretical to America’s vision of itself is to some extent born out in the literature of Hawthorne and the decidedly murky regimes of tyranny, bigotry and intolerance under which the citizens of the New World were forced to live in the early days. Quakers, for example, were persecuted, suppressed, tortured and discriminated against in much of New England throughout the early years of the colonies. But I suppose the tortuous alteration of real history and the elevation of the Pilgrim Fathers to heroic status was important for America, which needed to create a vision of itself consonant with its lofty aims. I dare say Robin Hood was a greedy cut-throat and Boadicea a cruel tyrant – all nations twist history and cleanse their heroes in order to express an ideal to live up to.

Nowhere in America is the religious intolerance and fanaticism of the early colonies more apparent, or more weirdly celebrated, than in the small town of Salem, MA.

The Witches

Halloween is the first of America’s great winter festivals of celebration and commerce, followed by Thanksgiving and completed by Christmas (or the Holidays, as they are usually called, in deference to non-Christians) and New Year. Children across America go trick-or-treating dressed up as ghosts, monsters, gore-spattered zombies or, somewhat inexplicably, superheroes. For weeks before the actual day houses and gardens (‘yards’) are decorated with scarecrows, gravestones, pumpkins and autumn fruits creating a weirdly pagan mélange of Wicker Man Celtic, Transylvanian Gothic and Parish Harvest Festival.

In the late seventeenth century an attack of mass hysteria in Salem, Massachusetts resulted in a series of witch trials, judicial torture and hangings. Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible famously used the episode as a metaphor for the Communist ‘witch-hunts’ of his own time. The shameful, primitive and disgusting events of the 1690s have receded into jokey folk lore and Salem now embraces its position as the Halloween and Olde Puritan capital of America, abounding with Publick Houses and Crafte Shoppes. Indeed there are now real witches in Salem, witches who are Out and Proud.

‘Can you feel the positive energy here?’

‘Er, well, since you mention it, not really …’

I meet High Priestess Laurie Cabot in her occult shop ‘The Cat, The Crow and The Crown’, the first of its kind, she claims, anywhere in the world. She and her co-religionists have fought long and hard for ‘the Craft’ to be treated as any other faith under the constitution. Laurie is the ‘Official Witch of Massachusetts’, a title granted by Governor Dukakis in the seventies. She is not to know that I am entirely allergic to anyone using the word ‘energy’ in a nonsensical, New Age way. A hundred years ago it would have been ‘vibrations’. I am determined not to be surly and unhelpful, however, so I plough on.

‘Big day for you, today, Laurie. Halloween.’

‘Today is not Halloween,’ she says, putting me right, ‘it is the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain. The Christians took it over, along with so much else.’ There is no black cat perched on her shoulder, but there might as well be. ‘The Christians went from persecuting us to scorning us for what they call superstition.’

I murmur sympathy, which is genuine. To me, all religions are equally nonsensical and the idea that Christians, with their particular invisible friends, virgin births, immaculate conceptions and bread turning into flesh, could have the cheek to mock people like Laurie for being ‘superstitious’ is appalling humbug.

Laurie invites me to a great Samhain meeting (I forbear from using the word ‘coven’ for I have an inkling it might offend); it is to be held not naked and out of doors, leaping through flames and around pentacles, but in the ballroom of The Hawthorne Hotel. No black candles, no reciting of the Lord’s Prayer backwards. This is not Hammer House of Horror but a kind of syncretic New Age mixture of Druidism, Celtic folklore and much vague talk about ‘energies’.

The meeting itself is a very charming party in which the Cabot-style witches who have come from all over the world to be here dress up, dance (to seventies and eighties pop mostly) and then come forward for a ‘circle’ in which a sword is waved, incantations are made and ‘energies’ invoked. It is all over very quickly and then Laurie and I get on with the business of judging the best costume of the evening.

Meanwhile outside, the entire town of Salem has turned into a huge horror and gore theme park. The smell of donuts and burgers, the sound of rock music, the sight of murder, mayhem and death. By twelve o’clock it’s all over and everyone is in bed. It seems to me that there is more true Gothic horror in a digestive biscuit, but never mind. Tomorrow I shall be immersed in the comforting sophisticated grandeur of the state capital.

Boston and Harvard Yard

I spend a morning in the city of Boston, ‘Cradle of the Revolution’, filming around the docks where the Boston Tea Party took place and searching (in vain) for Paul Revere’s house. Revere was the patriot and hero whose midnight ride from Boston to Lexington shouting ‘The British are coming!’ is still celebrated in legend and song. The apparent address of his house defeats the taxi’s satellite navigation system and after driving around Boston’s Chinatown asking puzzled citizens for ‘the Revere House’ I find myself in desperate need of a cup of tea.

It so happens that I have heard of a place across the water in Harvard Yard where, almost uniquely in America, a proper cup of tea can be had. If you can pronounce ‘Harvard Yard’ the way the locals do, you can speak Bostonian. It’s more than I can manage – I contrive always to sound Australian when I try. The ‘a’s are almost as short as in ‘cat’, even though they are followed by ‘r’s. Impossible.

Harvard University is America’s Cambridge. So much so that the town it is in, over the water from Boston, is actually called Cambridge.

Those who like good old-fashioned English ‘afternoon tea’, with proper sandwiches and proper cakes, and tea that isn’t the etiolated issue of a bag dangled in warm water, those who like to meet pert young students and trim graduates and twinkly, stylish professors, all congregate gratefully at the weekly teas held by Professor Peter Gomes, theologian, preacher and a natural leader of Harvard society. He dresses like a character from the pages of his favourite author. When asked to offer his list of the Hundred Best Novels in the English Language for one of those millennial surveys in 1999 he lamented, ‘But any such list will always be four short! P.G. Wodehouse only wrote ninety-six books.’

Black, gay, intensely charming, a connoisseur and an anglophile, Gomes is not what you expect of a Baptist minister, a Baptist minister furthermore who (though now a Democrat) was something of a chaplain to the Republican Party, having led prayers at the inaugurations of both Ronald Reagan and George Bush Snr.

‘I was a Republican because my mother was a Republican and her mother before her. That nice President Lincoln who freed the slaves was a Republican and our family chose not to forget that fact.’

The downstairs lavatory in his beautifully furnished house is filled with portraits of Queen Victoria at various stages of her life, from young princess to elderly widow. I emerge from it murmuring praise.

‘Ah, you like my Victoria Station!’ beams Gomes, ‘I’m so happy.’

‘You’re obviously gay,’ I say to him. ‘But some people might be surprised to know that you are also openly black … no, hang on, I’ve got that the wrong way round.’

He bellows with laughter. ‘No, you got it entirely right, you naughty man.’

‘Your command of language, your love of ornament, literature and social style … is that regarded by some as a kind of betrayal?’

‘Someone once called me an Afro-Saxon,’ he says. ‘It was meant as an insult, but I take it as a compliment.’

I am sorry to leave the elegance and charm of Harvard, but there is plenty more elegance and charm awaiting me up ahead in Rhode Island.

RHODE ISLAND

KEY FACTS

Abbreviation:

RI

Nickname:

The Ocean State

Capital:

Providence

Flower:

Violet

Tree:

Red maple

Bird:

Rhode Island red chicken

Drink:

Coffee milk

Motto:

Hope

Well-known residents and natives:

General Burnside, Dee Dee Myers, H.P. Lovecraft, S.J. Perelman, Cormac McCarthy, George M. Cohan, Nelson Eddy, Van Johnson, James Woods, the Farelly Brothers, Seth ‘Family Guy’ MacFarlane.

RHODE ISLAND

‘I do not especially mind being asked as a guest onboard a boat, so long as I do not have to do anything more than sip wine.’

Wedged between Massachusetts and Connecticut and very much the smallest state in the union, the anchor on Rhode Island’s seal and its official nickname of the ‘Ocean State’ tell you that they take nautical matters seriously here …

The Cliff Walk

From about the middle of the nineteenth century wealthy plantation families from the South began to build themselves ‘cottages’ along the clifftops of Newport, where they could escape the insufferably humid heat of the Southern summer and enjoy the relatively bracing and comfortable breezes rolling in from the Atlantic. Over the next few decades rich Northern families began to do the same as the Gilded Age of Vanderbilts and Astors reached its imponderably wealthy, stiflingly opulent and dizzyingly powerful zenith. These cottages were in fact vast mansions, some of seventy rooms or more, designed to be lived in for only a few months of the year, but all displaying the incalculable and overwhelming riches and status that the robber barons and industrialists of post-Civil-War America had heaped up in so short a time. Never in the field of human commerce, I think it is fair to say, had so much money been made so fast and by so few.

Today the cliff walk between Bellevue Avenue and the sea is a tourist destination and many of the grander cottages are owned and run, not by their original families, but by the Newport County Preservation Society and other trusts and bodies dedicated to keeping these gigantic fantasies from crumbling away.