Полная версия

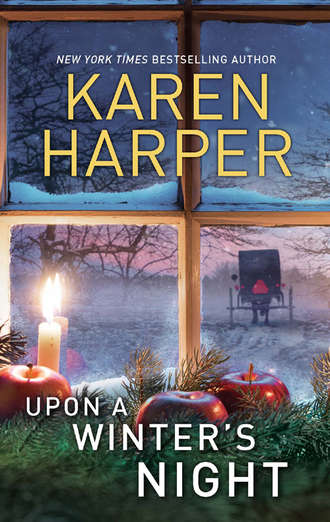

Upon A Winter's Night

They all hurried toward him.

“I left her out there, ’cause she’s dead for sure,” Josh told them, out of breath as he led Blaze in, dragging the sleigh across the floorboards. “Frozen to death or something else, can’t tell. I’ll take anyone out there who wants to go. I left her like she fell, except for Lydia’s cape over her, in case there was any foul play.”

“Good thinking,” the sheriff said.

Connor faced Josh. “Foul play? That’s ridiculous! She’s out of her head! She just wandered off and picked a deadly time to do it.”

Sheriff Freeman ignored the outburst, but Lydia and Ray-Lynn exchanged uneasy glances.

“I’m the only one going with you, Josh,” the sheriff said, then got back on his phone. Lydia realized he was talking to the county coroner.

Connor’s shoulders slumped, and he walked away, punching numbers into his cell phone, evidently to call his wife or his mother. Lydia thought for sure he had huffed out a sigh of relief—or was it exasperation?—when he’d heard his aunt was dead, but then she knew from her own family that people handled shock and grinding grief in different ways.

Oh, ya, she thought as her father arrived at the far door with her mother hurrying ahead of him toward Lydia. She sure knew all about that.

* * *

Lydia wanted to stay in the barn until Josh and the sheriff came back from the field. She felt she should in case the sheriff had questions for her. But her parents insisted she go home with them and the sheriff could interview her later. Ray-Lynn said the men would be out there a long time, waiting for the coroner, and she was supposed to go home, too.

With a buggy robe wrapped around her like a shawl and another one over her knees, Lydia sat wedged between Mamm and Daad on the short journey home. It was so cold it hurt to talk, but Mamm was doing it, anyway.

“See what I mean about the Starks? Ach, who knew they had an ailing aunt stashed over there? Secrets all around, oh, ya. I wouldn’t be surprised they took her in just so when she passed they could get her money, too.”

“That’s enough,” Daad said.

“Well, she’s a Keller, evidently an old maid Keller, and it was her and Bess Keller Stark’s family that had the seed money for all they do. Obviously, they can buy anything they want, including people’s silence, because they must have had someone taking care of her. Connor just grows and sells those pine trees so he’s not completely bored playing big man in town and now mayor.”

“Let’s not judge others,” Daad said.

“I try. I tried for years, but I’m only human. And, Lydia, see what a stew you got yourself into working over there with those animals!”

“It was a blessing I found her body, Mamm. And we’ve discussed my working with the animals before. Christmas is coming, and Josh needs help preparing them for manger and crèche scenes. It’s a good service to let people know about the real meaning of Christmas, and anytime people mingle with animals, it reminds them of God’s creation.”

“Don’t you preach at me, too.”

And that was that until they were home. The two women hurried into the house while Daad stayed behind in the barn to unhitch and rub down the horse. Lydia went upstairs to take a hot bath, but, as usual, the frosty air between her parents didn’t thaw even later when Daad stomped into the mudroom at the back of their big house and Mamm stood stiff-backed at the stove, making them cocoa and putting out friendship bread and thumping down jars of apple butter and peach preserves on the table.

Lydia thought Daad had been out in the barn pretty long on such a cold night, but it seemed he always spent hours out there as well as at the Home Valley Amish Furniture store he’d inherited from his father and had built up even more. Then, too, Solomon Brand often spent time in the side parlor of their house with the secret he kept from all the world except his wife and his daughter: Sol Brand loved to hand quilt.

True, that traditional craft belonged in the realm of Amish women, like keeping the garden, and making clothing and watching the kinder. But he was so skilled at it with his tiny, even stitches, intricate patterns and unique colors, especially for a man who oversaw carpenters, joiners, sanders and stainers at the store workshop. Neither Susan, though she belonged to a quilting circle, nor Lydia, who draped some of his quilts near the oak and maple bedsteads and headboards they displayed at the store, ever admitted who was the maker of his stunning quilts.

Besides luring customers into the store, his “Amish-made” quilts covered beds and lay like buried treasure in the chests and closets of their home. Amish women never signed their handwork, anyway. Many were cooperative efforts, and no one wanted to be prideful by boasting or asking who made the ones for sale. But how often Lydia had wanted to tell someone, “My daad made that, and isn’t it grand?”

Once, she recalled, Sammy had blurted out to several church leaders that his father “quilts,” but he was such a youngster that Bishop Esh had thought he’d said “Daadi builds.” One of the elders had said, “Oh, ya, but really he oversees what other men build at the furniture store.” And, of course, Sammy, flesh of her parents’ flesh, while Lydia sometimes felt bone of their bone of contention, never got scolded for telling the family secret. Oh, no, Sammy never made a mistake. Except the day he disobeyed and sneaked out of the house to go swimming in the pond when he was told to take a nap because he’d had a summer cold—and he drowned.

Lydia had heard his desperate shrieks. Mamm, hanging clothes, had, too, but they were both too late by the time they ran clear out there. Lydia had thanked the Lord more than once that she wasn’t supposed to watch him that August day but had been told to weed the side garden. She could not imagine his death having been her fault. But it was so sad that her mother had never stopped blaming herself.

How different Connor Stark had reacted today when a member of his family wandered out and died. Though he’d said they had hired help watching his aunt, would he blame his wife over the years for not seeing Victoria Keller sneak out the way Daad must surely blame Mamm? Or so Lydia had figured all these years since they were always on edge.

After her little brother was lost, it had come as a shock to Lydia when her father told her, with her mother hovering, that she had been adopted when her parents, Daad’s distant cousins, were killed in a buggy-car accident. She had only been an infant—and, thank the Lord, Daad said, she was not in the buggy with them.

She’d cried and cried at first, but Daad had assured her that the accident meant she was chosen to be their child, not just given from on high. And Mamm had blurted out once that they had believed Sammy was a special gift from God because they’d taken Lydia in. Just like Sarah and Elizabeth in the Bible, all those barren years—and then a son!

But to be adopted in Amish country with its big families was something that marked Lydia, at least to herself. Even though people seldom mentioned it, she felt she carried that scar deep inside. She had tried to talk about it with Bishop Esh. He had said that the Lord and her parents loved her very much, and that she should “learn to be content” and ask no more questions about her “real” parents—that Solomon and Susan Brand were her real parents.

* * *

Josh knew he wouldn’t sleep even though things were calm now. Finally, silent night. The storm had diminished to spitting snow; the sheriff and the coroner’s van had gone; Mayor Stark had finally departed, too, once he’d viewed his aunt Victoria’s body to identify her. Turned out the woman was only sixty, though in death she looked much older.

Carrying a lantern, Josh left the barn and slogged through the new foot of snow to his house to be sure the faucets were all dripping to keep the pipes from freezing. He wanted to build up the stove and hunker down by it, but he was too restless, running on adrenaline, as they said in the world he had sampled for four years.

He had liked living in Columbus, working with ruminants at the zoo, getting to know the famous and admired Jack Hannah, the former zoo director, who had built the place up to one of the best in the country. Josh had learned some important things about vet medicine, the history and habitats of different breeds, and animal conservation in the wild. But his people, his calling—the dream of having his own animals to share with others—had brought him back to the Home Valley.

The big house he’d grown up in felt achingly quiet and lonely tonight. Its bones creaked in the cold. How would it be to have a family to fill the place, a wife waiting for him, kids calling down the stairs, his own little band of workers for his furry, hairy crew?

He locked the farmhouse again and trudged back to the barn. Despite the cold, he’d sleep on his cot there tonight, comforted by the gurgles of the camels and the snorts and snuffles of the other animals. An occasional baa or moo never bothered him. Hopefully, the donkeys were asleep, his security alarm system for now, though come spring he was going to buy a couple of peacocks to take over the job. No good to have tourists arriving with youngsters for a petting zoo and hayride only to be greeted by barking watchdogs.

It bothered him that Lydia had found the back gate ajar, though Victoria Keller must have been the one who opened it. Lately, Amish kids in their running-around years had sneaked in that way, so maybe he needed to put a padlock on it. It was hard to get used to that kind of thinking, but major crimes had found their way into Eden County. When he was growing up, a lot of folks didn’t even lock their houses.

He had generator-powered blowers and heaters in the barn—which blew out cool air in the summer—and he shoved his cot over so he’d be in the draft of warm air. He put the single lantern on the board floor far away from any loose hay or straw. He saw Lydia’s cape on his cot where he’d spread it to dry—ya, the blowers had done that now, and he’d be sure she got it back tomorrow. He hoped her parents would still let her help him after all this. The cape even smelled of her, though he knew she didn’t use perfume. It was a fresh scent that reminded him of nature, of the outdoors and freedom. Lydia was a natural with the animals, as well as a natural beauty.

Groggy with exhaustion, he lay down and tugged up the two blankets and her cape over him, the cape she’d given up to help warm that poor woman. He hugged it to him, thinking of how he’d hugged Lydia tonight. She meant more to him than just a helper, just the girl—woman—next door that he’d thought of as a kid most of his life...

But it was pretty obvious she was to be betrothed to Gideon Reich. Josh didn’t know the man well, but he had piercing eyes and a big, black beard when most Amish men had hair and beard that were blond, brown or gray. Ray-Lynn at the restaurant had told him that Lydia and Reich were tight, said they sometimes came in together for lunch. Lydia never mentioned the man, but with the Plain People, courting was often private until the big announcement of the betrothal, followed several months or even weeks later by the wedding. Reich’s house was way on the other side of town, so Josh knew he’d lose her help—lose her—when she wed.

Sometime in the dead of night, Joshua Yoder dropped off to sleep and dreamed of an oasis in the desert with a warm wind and camels and black-bearded Bedouins and a veiled woman. No, that was a prayer kapp. She had big, blue-green eyes and then her kapp blew off and her long, honey-hued hair came free. He went out into the sandstorm and picked her up in his arms before anyone else could get to her. When he lay down again, she gave him a big hug and then he kissed her and held her to him and pulled her into his bed.

* * *

It was the dead of night, but, in a robe and warm flannel nightgown, Lydia sat at the kitchen table, sipping cocoa, remembering how Josh had poured her some of his cocoa, even raised it to her lips. How warm his coat had been around her, and then that hug he started but she finished well enough.

“Lydia,” Mamm’s voice cut into her thought. “You’re daydreaming again, and that’s a waste of time. Wishing and wanting doesn’t help.”

Lydia knew better than to defend herself, so she just reached for a piece of bread. Mamm started to make up her grocery list as if nothing unusual had happened tonight. Daad sat at the other end of the table, eating, quiet. Lydia was aching to talk about finding the woman, and a thought hit her foursquare: that note the dead woman had in her hand was still in her mitten.

She stood and hurried into the mudroom where she’d left it. Not much of the message could be read, she recalled, but what had the remaining words said? She’d have to tell the sheriff, give the note back to Connor or the deceased woman’s sister, Bess, when she returned for the funeral—if there was a funeral, given how secretive they had kept Victoria Keller’s presence. Word about a strange recluse living in the mayor’s mansion would have traveled fast as greased lightning in this small, tight community.

Lydia checked the first mitten pinned to their indoor line. Nothing. Had she lost it? But there it was in the other mitt, still damp.

Lydia held the paper up to the kerosene lantern hanging in the window and squinted at the writing, mostly blue streaks.

“What’s that?” Daad asked, popping his head around the corner.

“Just something I forgot,” she said.

“Don’t mind your mamm’s fussing,” he said, keeping his voice low. “Dreams are fine if you are willing to work for them.”

“Danki, Daad,” she told him. She almost showed him the note, but as he went back out she was glad she hadn’t. When she tipped it toward the lantern, she could read a few of the words, written in what looked to be a fancy cursive in a hand that had trembled: To the girl Brand baby... Your mother is—

She couldn’t read that next word for sure. Your mother is alert? Your mother is alike? No, it said, alive. Alive! Your mother is alive. And I... And I, what? Lydia wanted to scream.

From the kitchen, Daad called to her, “Don’t worry about talking to the sheriff tomorrow or on Monday, Liddy. I can be with you when he interviews you, if you want.”

“Danki, Daad, but I’ll be fine. There isn’t much to say.”

Alone in the dim mudroom, Lydia stood stunned. Alive? Your mother is alive? And I...

She’d just told Daad there wasn’t much to say. But after tonight—finding Victoria Keller, Josh’s hug, now this—she wouldn’t be fine, maybe ever again.

She had to be “the Brand baby,” didn’t she? Everybody knew who Sammy’s mother was, and she was the only girl. Dare she share this with the sheriff, the Starks or even her own parents? And could she trust a demented woman that her mother was still alive?

3

Lydia was grateful for a quiet Sabbath morning. It was the off Sunday for Amish church since the congregation met every other week in a home or barn. Daad always said a special prayer after the large breakfast Mamm and Lydia made before they went their own ways for quiet time. But Lydia hadn’t slept last night. Her mind had not quit churning and she couldn’t sit still.

In her bedroom, she stared again and again at the note she’d taken from Victoria Keller’s hand. Had it been meant for her, or at least was it about her? Then why was the woman evidently heading for Josh’s big acreage? Or, since she had what Connor called dementia, had she mixed up who lived where in the storm, stumbled on past the back of the Brand land and the woodlot and gone in Josh’s back gate by mistake? Surely she wouldn’t know Lydia worked for Josh. If the woman was one bit sane, she would not have gone out in that storm, or had it surprised and trapped her, too? And why now? Why had she waited twenty years after the Brand baby had been born—if it referred to Lydia—to deliver the note?

Yet Lydia felt that finding the woman and the note must have been a sign from heaven, a sign that she should not only learn if the note was true but also find out more about her real parents. She’d had questions pent up inside her for years. She didn’t want to hurt her adoptive parents or make them think she didn’t love and respect them, yet she had to get to the bottom of this, maybe without telling anyone. But she knew she’d be better off getting help. She had to start somewhere.

A car door slammed outside. She went to her second-story bedroom window and glanced down. It was Sheriff Freeman, in his uniform and with his cruiser this time. She slid the note she’d dried out between two tissues back into an envelope and put it under her bed next to the snow globe. When she was twelve, her father had given that to her and said not to tell Mamm, that it had belonged to her birth mother and had been left by someone at the store. No, he’d insisted, he knew no more about it.

Lydia smoothed her hair under her prayer kapp and went downstairs as she heard the sheriff knock on the front door. His words floated to her before she got all the way down the staircase.

“Afternoon, Sol, Mrs. Brand. Oh, good, Lydia. I knew there wasn’t Amish church today but wanted to give you some catch-up time after last night, and Ray-Lynn and I were at church. Lydia, Ray-Lynn’s on a committee for our Community Church doing a living manger scene, so we’re hoping to use some of the animals you help tend.”

“Oh, that will be good. Josh will be happy to take the animals to a church that’s nearby. He and his driver, Hank, usually have to go much farther.”

Daad gestured them into the living room and, to Lydia’s chagrin, sat in a big rocking chair near the one the sheriff took. Lydia perched on the sofa facing the sheriff while Mamm hovered at the door to the hall.

“Always admire the furniture from your store,” the sheriff said, taking out a small notebook and flipping it open. “Hope to buy Ray-Lynn a corner cupboard there real soon. Now, since Lydia’s the one I need to talk to—won’t take long—I hope you won’t mind giving me a few minutes alone with her. Turns out the victim, Victoria Keller, suffered a blow to the back of her head. That could be significant—or not—since she wasn’t real steady on her feet. The coroner will rule on that. Meanwhile, I’m trying to put the pieces together.”

Daad said, “I’d like to sit in. Won’t say a word, and Susan can fix us some coffee for after you’re done.”

He shot his wife a look; Lydia sensed Mamm would refuse, but she went out.

“I understand your protective instinct,” Sheriff Freeman said to Daad, “but your daughter’s able to answer on her own as an adult.”

“That she is. I will be in the kitchen with my wife, then,” he said, slapping his hands on his knees. “I know Liddy will help you, though she doesn’t know much besides finding the woman and leaving her cape. And she shouldn’t have been out looking for a camel in that storm. Josh Yoder should take better care of his animals over there.”

Though she had several things to say about that, Lydia kept her mouth shut until her father left the room.

“That’s terrible about the blow to her head,” she said, leaning farther forward, hands clenched on her knees. “But in her condition and that storm, it doesn’t mean someone really hit her, does it? I think she might have had trouble opening the gate, because I had trouble closing it, dragging it through the snow the wind had piled up there. But unless she fell into it, I doubt it could hit her hard. It wouldn’t swing open or shut in that snow.”

“Okay, that’s a start. She may have hit her head on the gate. Now tell me what you saw from the beginning.”

Lydia talked about looking for Melly, how the camel liked to cling to the fences. “Her real name is Melchior,” she told him, feeling more nervous every second. “The other two Bactrian camels we—I mean, Josh—has are Gaspar and Balty, short for Balthasar. You know, the traditional names of the three wise men. The three dromedaries he owns are Angel, Star and Song. He needs at least six to cover the manger scenes and pageant orders, like you mentioned Ray-Lynn’s in charge of.”

“And Bactrian means...?” he asked, pen poised, looking up at her.

“Oh, sorry. Bactrians have two humps, and dromedaries have one. It’s really not true that camels are nasty, though if mistreated they can spit and balk, but Josh’s are not that way. Camels are like dogs in that respect—some good, some bad, all depending on how they’re treated, and Josh is good to his.”

“So you believe a camel, this Melly, even if she was startled or panicked in the storm, wouldn’t slam into or kick someone who should not be on the grounds?”

“Melly? Oh, no. She might be curious, but— No.” Lydia’s heartbeat kicked up. “You don’t think that Melly knocked her down?”

“Don’t know what to think yet. What about if the woman was already down and Melly stumbled over her? Josh says Melly just came loping into the barn by herself and that’s when he realized you might be the one missing.”

Her mind racing, Lydia stared the sheriff down. Surely someone like Connor wouldn’t insist Melly be put down or give Josh trouble over this. It was his aunt who was trespassing, poor soul, not the camel.

“No, Sheriff,” she said. “I don’t think Melly would kick her, and if she stumbled over someone already on the ground, it was an accident.”

“Okay, so is there anything else you can tell me about what you recall, anything at all?”

Lydia thought she could hear someone in the hall. Mamm with the coffee? Daad waiting until they were done? Now, right now, she should tell the sheriff about the note she found, but it was so confusing, only a partial message, and so—personal. Hadn’t the Lord meant for her to find it and use it? Maybe the sheriff could help her learn what it meant, but wouldn’t that make it all public again that she was adopted, upset her parents... She started to sweat, her stomach cramped.

“Lydia? You all right? Is there something else?” the sheriff asked, leaning closer.

“Oh, sure. I— Of course, you know this, but I put my cape over her, tucked it in, so I hope I didn’t disturb anything.”

“Right—the cape. I took a good look at it, no blood. I told Josh he could give it back to you. So, that’s it?”

She nodded, perhaps a bit too hard, as if she were a little kid defending a fib. This man was used to putting clues together, figuring out when someone was lying or guilty. Did he know something was wrong, that she’d held information back, maybe something very important?

“Okay, then,” he said, and rose, flipping his little spiral notebook closed and putting it in his shirt pocket. “The Starks are planning a small, private funeral later this week. Connor said you’d be invited for all you did to try to help his aunt.”

“I’m sorry she was mentally ill and so young—I mean, even at sixty, that’s young to—to lose your mind. And she had no family but the Starks here?”

“Never married, no children. And now she’s not even alive...”

Your mother is alive. And I... The haunting words of the note echoed in Lydia’s head and heart.

Mamm suddenly appeared in the doorway with a tray of mugs and a plate of sliced friendship bread, and Lydia hurried to help her.

* * *

Josh had to admit he was nervous, taking Lydia’s cape back to her house. Over the years, he’d visited there various times, but everything felt different today. And it was a Sunday, when unwed Amish men, termed come-calling friends, visited women they hoped to court and eventually marry. If it had been a church day, he’d have been sure she got the cape back before this.

No doubt, in a family as well off as hers, she’d have more than one cape. He’d actually had to get out his iron and ironing board to smooth it out after he’d evidently bunched it around and under himself last night. That kind of labor was frowned upon on the Sabbath, but he could hardly give the cape back in a wrinkled mess, even though it had been tucked around the dead woman in the snow.

Victoria Keller died alone, yet she’d received that loving act of kindness on her cold deathbed. He shifted uneasily on his buggy seat. Would that be his fate when he died—the kindness of a stranger—if he never wed?