Полная версия

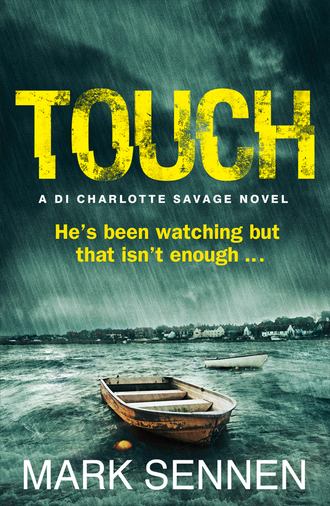

TOUCH: A DI Charlotte Savage Novel

‘He knows I enjoy a nice summer jaunt in the country,’ Savage said, indicating the autumn storm howling overhead. ‘What have you got there?’ She gestured at the mass of mud at Layton’s feet.

‘Tyre prints and footprints. The whole thing is a bit of a mess because we have got the farmer’s as well but we might get something. Lifted a couple of good fingerprints off the gate too.’

‘Can I go down?’ Savage nodded towards the tape running down the field.

‘Sure. One of my guys and a couple of photographers are at the scene already.’

‘Pathologist?’

‘Stuck on the A38 somewhere.’

‘If it’s Nesbit he won’t be happy.’

‘It is Nesbit, and no he didn’t sound too pleased when he called to tell me he was late.’ Layton paused and looked down at Savage’s feet. ‘The field is a complete bog. Got some wellies in the back of the van if you’d like?’

Savage said she would and Layton dug out a pair of yellow boots as well as the obligatory white coverall. Her feet slid around inside the over-sized boots, but as she walked down the side of the field she was grateful for them. The cattle had made much of the pasture a quagmire and the saturated ground oozed underfoot.

The tape ran down to where it was tied to a small aluminium step ladder the CSIs had put up to span the fence. A few metres farther on fence posts and netting lay in a flattened tangle and Savage noticed tyre tracks leading from the pasture into an earthy field where green shoots of wheat or some other crop poked up through the soil. The tyre marks crossed the neat tramlines of tractor tracks and curved left down towards a small patch of woodland at the bottom of the valley.

Savage climbed over the ladder into the next field and followed the tape again. As she neared the trees the clouds seemed to crowd overhead, darkening the sky even more. A stile led into the copse and to its right some more fencing had been removed. She walked through the opening into a little grove with towering old oak trees and slender young ash.

A sudden flash of harsh white light from a camera lit up a white crime scene tent and through the open end Savage could see a pale body lying like a sleeping nymph from a fairy tale. Two people stood next to the body on plastic stepping plates, one taking the pictures, the other with a small video camera. She recognised the photographer as Rod Oliver. His silver hair and craggy, weathered face showed he was getting on in years, but he knew his job. A year or so ago he had gone independent and filled in his spare time doing wedding shoots. Two more disparate sets of clients were hard to imagine. At the far edge of the clearing another figure in white combed the scrub with a long metal probe, teasing the long grass and nettles apart. Savage didn’t go any closer but she could see the corpse belonged to a young woman, late teens or early twenties. White skin, no clothing, hands by her sides, legs apart. She didn’t appear dead, just as if she was resting for a while. Her angelic face stared skyward towards heaven, but although the nakedness hit Savage like an electric shock, there was nothing else of note.

She looked around at the woodland. On a summer’s day with a picnic and a family and laughter and smiles this would be an idyllic place. Today an autumn chill seeped from the ground and the wind whistled through the trees. The scrub and brambles appeared to be creeping into the clearing, trying to cover everything, to wipe out all traces of humanity and reinstate the wilderness.

Oliver noticed her and walked back along the row of stepping plates. As if reading her mind he told her what he knew.

‘At first sight no obvious cause of death, although there is a strange cut mark on the belly. I would hazard a guess drugs are involved. Also, clever young Matt spotted a couple of indentations in the moss between her legs.’

Oliver introduced the pale-faced guy with the video camera as his assistant. Savage didn’t think Matt looked young or clever, but when you went independent you would have to keep a tight rein on costs, she thought.

‘There’s a substance on the pubis and stomach resembling semen,’ Oliver continued. ‘I’d say somebody knelt and ejaculated over her. Although it’s not my job to speculate, of course. Doc Nesbit will be able to confirm the drugs angle.’ He nodded back towards the edge of the copse where a figure in a full white coverall plodded their way.

‘You’ve seen everything, Rod,’ Savage said. ‘You probably know more than half the guys in the business. And it is a business now, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, for me at any rate. Although I must admit I find it hard to put in an invoice after I have been to a scene like this. Doesn’t seem right somehow.’

Savage knew what he meant. She often struggled with what the job involved, but with her the emotion didn’t involve guilt about the money. Her own guilt was about how much she enjoyed the excitement. Not this bit of course, not the death and the misery, but the rest of the process; from not having a clue to having them bang to rights. Sometimes it seemed inexorable and unstoppable as if mapped out by some greater being and all she had to do was follow a path leading to the criminals. Savage didn’t have much time for religion, but there was something comforting about the fact that right beat wrong and justice always prevailed. Well, nearly always.

Savage heard a cough behind her and turned to see Doctor Andrew Nesbit, the pathologist. His half-round glasses identified him as much as his slight stoop, which he claimed he had developed from bending over too many bodies. Nesbit was old-school and beneath the coverall Savage knew he would be wearing a tweed jacket and tie, an outfit in which he could be – and sometimes was – mistaken for a country doctor. He had a polite bedside manner, full of charm and grace, but this was lost on his patients since invariably they were dead.

‘How’s that little MG of yours, Charlotte?’ Nesbit said.

‘She’s tucked up in my garage for the winter, thank you very much. Still costing me though. New sills done in the summer.’

‘The AA badge must be the only thing you haven’t renewed.’

‘Very funny, Doc. But you are right, totting up the bills does make me feel like I have bought five cars’ worth of spare parts.’

‘What about your boat? I saw the picture in the paper back in the spring. You, Pete and the children.’

Savage remembered the Herald had done a feature on Pete before he set off for the South Atlantic, a photo shoot with the whole family on their tiny yacht. The journalist had been tickled pink by the contrast between helming the little coastal cruiser and commanding the oceangoing warship.

‘Took the children out a few times in the summer, but managing the boat on my own is a struggle and I can’t seem to persuade Stefan to join me. If he isn’t cold, wet and leaning over at forty-five degrees he doesn’t think he’s sailing.’

‘Samantha is growing up fast. And turning into the spitting image of you with all that red hair. Very beautiful.’ Nesbit smiled, a twinkle in his eyes.

Savage blushed, even though she knew Nesbit’s words were small talk intended to make everyone feel relaxed in a stressful situation.

‘Ah, well.’ Nesbit shrugged. Then he moved past Savage and walked over the stepping plates and into the tent to examine the body. ‘I overheard you telling Charlotte about drugs,’ he told Oliver as he bent over. ‘No way I can confirm that here of course. And looking at the body now I’m not sure you are right about there being no sign of obvious trauma.’

Nesbit knelt, opened his bag, put on some nitrile gloves and took out a flat wooden spatula. He pressed the rounded end against the girl’s stomach, opening the cut Oliver had pointed out.

‘The incision on the abdomen is deep, the hole goes right in. Hasn’t bled though. Strange.’ He moved his hands up and touched the girl’s breasts and then probed her right arm. ‘The skin doesn’t seem quite right either and there is an odd smell, more a fragrance.’

‘Soap?’ Savage suggested. ‘Could she have been washed?’

‘Possible, the skin is a bit puffy,’ Nesbit paused. ‘But there is something worrying me. Can’t quite figure it out at the moment.’

‘Do you think she was killed somewhere else?’

‘Appears that way. Note the lividity in the buttocks and upper thighs? She was in a sitting position at or soon after death because the blood has pooled there. Quite unusual.’ Nesbit looked around, eyes drinking in every little detail. ‘No sign of a struggle taking place here, but I noticed several sets of footprints in the moss.’

Nesbit pointed towards the path and Savage spotted some indentations in the bright, green carpet, a trail leading to and from the girl’s body. They would have to work out which belonged to the killer, which to the farmer, and which to the PC who had first attended the scene.

‘Finished for the moment?’ Nesbit asked Oliver.

‘Yes, got a camera full, close-ups of all of her from tip to toe.’

‘Good.’ Nesbit took a digital thermometer with a remote probe from his bag and called across to the CSI. ‘Can you help me, please?’

Nesbit instructed the CSI to roll over the body and then he bent and inserted the probe into the girl’s rectum. While Nesbit did this Savage reflected on the fact that dignity and suspicious death were incompatible and that there would be far worse to come on the post-mortem table. Nesbit told the CSI to let the body lie flat again and he placed the thermometer display down on the ground. A few seconds later the unit beeped and Nesbit peered at the screen and muttered something Savage didn’t catch.

‘Doc?’

‘Strange. The core body temperature is way below ambient which is … what? Eight, nine, ten? I’ll measure it in a moment. Overnight I am sure it wasn’t much lower, not with this weather coming in off the Atlantic. It’s evident she has been dead for a day or two and kept somewhere colder.’

‘We had frosty weather last week and into the weekend,’ Savage said.

‘Yes. Perhaps the body was outside in another location and was moved here. That would explain the low temperature.’

‘There’s no way this could be an accident, some kind of …’ Savage wasn’t sure how to finish the question, not even sure why she was trying to grasp for an explanation other than the obvious one.

‘I can’t tell that here can I, Charlotte? Given the sexual angle I wouldn’t have thought this is anything other than murder, would you? Sorry. I know you need some luck at the moment. For this girl though it has all run out.’

Nesbit glanced at his watch and then pulled out a little voice recorder and mumbled something into the microphone. Then he stood up straight and was silent, a sombre expression on his face. Savage knew he wasn’t religious, but it seemed as if he was waiting for someone to say a few words or for something to happen. As if on cue the church bell began to strike the hour.

Gordon Isaacs was the farmer who had discovered the body and even before she had met him alarm bells were ringing in Savage’s mind. Not reporting a minor car crash or a theft to the police might be understandable, but when you had found a naked and dead girl on your land such negligence was unfathomable.

Calter and Enders had arrived from Plymouth and they piled into Savage’s car and drove up to Isaacs’s farm to see what he had to say for himself. The holding stood alone with no near neighbours and the feeling of remoteness from the safe, modern world grew as they lurched along the concrete road leading up from the lane and climbed across open hillside to a huddle of barns and an old farmhouse. Three abandoned tractors and a multitude of rusting farm machinery lay either side of the track. Blue fertiliser sacks replaced windows in several of the barns, baler twine stitched holes in fences and nettle, dock and brambles vied for supremacy everywhere. The place looked more like the local tip than a farm. The only thing pretty was the view. The countryside rolled away to the south in a patchwork of fields, woodlands, hamlets and villages. Somewhere beyond lay the urban sprawl of Torbay, hidden in the murk that clouded anything more than a few miles distant.

‘Look at that, ma’am.’ Enders pointed to a bonfire where a blackened and bloated corpse of a sheep was smouldering on top.

‘Devon-style barbie,’ Calter said. ‘Lovely!’

A house stood to their right as they entered the farmyard, a pretty cottage built of stone with a thatched roof half-covered with moss. To their left a crumbling brick barn was a Health and Safety nightmare with a broken asbestos roof that had been patched with rusty corrugated iron. Ahead a traditional byre was also dilapidated, but surely ripe for conversion.

They parked next to an old Landrover with an out-of-date tax disc and a cracked side window. As they got out Savage caught a whiff of burning sheep mixed with an odour of cow shit and silage and the smell clawed at the back of her throat as they picked their way through the mud to the farmhouse front door. Savage knocked, and as they waited she heard loud classical music from inside the house. And the sound of machine gun fire.

‘Huh?’ Savage cocked her head on one side, trying to make out the cacophony coming from within. It sounded like a TV set on maximum volume.

‘Platoon, ma’am, the film, I recognise the theme,’ Enders said. ‘The DVD was free with the Mail a week or two back. I’d love to watch it again, but I don’t get the chance to see what I want these days. The missus seems to think the kids prefer In the sodding Night Garden.’

‘Sensible woman.’

‘Funny thing to be watching when you’ve just found a dead body on your land,’ Calter said.

The sound from inside stopped and a moment later the front door swung wide to reveal a short and rather portly man with a large reddened nose and a wheeze that came before he spoke.

‘Yes?’

‘Detective Inspector Charlotte Savage. Can we come in, Mr Isaacs? We need to ask you a few questions.’

‘What more? I’ve had you guys trampling over my land, blocking the road so the feed lorry can’t get up here, and now you? I’ve got work to do, not time for questions to answer.’

‘You were watching a movie,’ Enders said.

‘None of your bloody business what I was doing, lad.’ Isaacs paused. ‘Anyway, the wife was doing the watching. She likes a good war film.’

As if to confirm what he said a figure appeared from the gloom inside and stood beside him. Mrs Isaacs had an appearance and stature not dissimilar to Mr Isaacs except her nose was dripping instead of red. She brought out a large stained handkerchief to deal with the drips and the tears running down her face.

‘Willem Dafoe. He just got shot to pieces by the slanties. Always affects me that bit,’ she sniffled. ‘Anyway, come in won’t you? If you wait for Gordon to ask you in you’ll be standing on the doorstep ’til Santa gets here with pigs pulling his sleigh.’ With that she turned and beckoned them in.

Savage made a gesture for Calter to stay outside and nose around while she and Enders followed the couple into the hallway. Newspaper was strewn across the floor and she was aware of her muddy footprints as she walked in. Enders nudged her and pointed down at the papers. The Daily Mail. She smiled and mouthed a silent ‘good work’. To the left was a living room, cold and unused, the furniture adorned with white dust-covers. To the right a smaller room, a snug she guessed you would call it, was more welcoming. Two armchairs and a sofa were arranged around a hearth, the coals glowing red and orange. A corner held a little television screen, on it an explosion with the same colours as the fire was frozen mid blast.

‘You’ll have some tea?’ Mrs Isaacs asked.

‘Thank you. That would be great,’ Savage said.

Mr Isaacs went over and slumped in the armchair nearest the fire, but made no invitation to Savage or Enders to sit. The two of them took the sofa and Savage began to ask about the discovery of the body. Mr Isaacs wasn’t interested. He had explained to the response team what had happened and was buggered if he was going to go through it all over again.

‘The problem is you said you discovered the body last night and yet you didn’t call us until this morning. I’m wondering why you took so long to phone us?’

‘Work to do. Things to sort. Animals and the like. Farm’s got to come first. Always has and always will. I still had loads of jobs to do and I thought if I called you lot I wouldn’t get the chance to finish any of them.’

‘The girl was dead, Mr Isaacs. Do you realise you committed an offence by not reporting the discovery straight away?’

‘She wasn’t going anywhere was she? I could see she was dead because I …’ Isaacs paused and huffed. ‘Well, I touched her. Had to. Didn’t know, did I?’

‘Didn’t know what, Mr Isaacs?’

‘I didn’t know if she was dead. She might have been sleeping.’

‘So when you realised she was dead, why didn’t you call us? It was obvious a crime had been committed.’

‘You’d know that, being police. I wouldn’t. I’m a farmer. Just a farmer. Anyway, I see death all the time. It’s not something alarming when you’ve got animals. Only yesterday I had to collect a ewe from down by the brook. Daft bugger had drowned herself, see? Brought her up here for disposal.’

‘We’ve seen the sheep carcass. It’s not legal is it? Burning them like that?’

Isaacs huffed again and started a rant on the European Union and politicians and how they knew bugger all about anything apart from lining their own pockets. Savage wasn’t unsympathetic when it came to the government meddling in affairs they didn’t understand, but the conversation was leading nowhere so she asked Isaacs if he had seen anyone yesterday, noticed anything suspicious, something out of the ordinary?

‘If I had seen anyone on my land they’d have known about it, so no, I didn’t see anyone.’

As Isaacs spoke Savage heard a tap, tap at the window and she turned to see Calter’s face beaming through. Calter motioned at Savage to come outside. Savage left Enders to continue the questioning and let herself out of the front door.

‘Over here, ma’am.’ Calter stood by the corner of one of the barns next to a bulging, blue fertiliser sack.

Savage went over to join her, squishing through mud and God-knows-what on her journey across the farmyard.

‘Something interesting?’

‘Oh yes!’ Calter held the sack open for Savage.

The sack bulged with various items of farm rubbish and at the top she could see a couple of syringes complete with needles along with an empty dispensing bottle. There were some wood offcuts, a few dirty rags, sheep daggings, bent nails, a length of rubber tubing, an old piece of rusty iron …

‘My eyesight must be going, Jane, I can’t see much of interest.’

Calter grinned and took a pen from her pocket. She poked one of the rags, looped it on the pen, retrieved it from the sack and held it out in front of Savage.

‘Oh no.’

The material had a bit of dirt on, but now it was free from the rest of the bundle Savage could see it was no rag, it was too clean for that. The pure white cotton wafted in the breeze as if drying on a washing line.

‘Girl’s panties, ma’am. Sainsbury’s own brand. The Isaacs don’t appear to have any young children and they are a wee bit small for the Mrs.’

Savage heard a noise and looked round to see the farmhouse door open. Mrs Isaacs’s shrill voice sang out across the mud.

‘Milk and sugar, Inspector?’

Chapter Six

Harry lay on the bed feeling the alcohol slither through his veins and watching the ceiling rotate above him. The plaster ceiling rose with the bulb hanging on the twisted wire went one way and the corners of the room went the other. After a while they each slowed down and almost synchronised before going in opposite directions again. Stagecoach wheels in cowboy films came to mind. He closed his eyes to remove the dizzying effect, but that only served to make him think about what he had done and what he had become.

Harry thought it was the blood that pushed him over the edge. The blood from Carmel had poured over his hands warm and sticky, the metallic taste still there days later when he’d absent-mindedly bitten a nail. He’d washed and washed but in the end figured memories took more than just soap to erase. He also blamed the pills. They had done evil things to him he was sure. When he stopped taking them he had flipped. And that was Mitchell’s fault.

He opened his eyes and watched the ceiling rose spin round again. Thought of roulette. Not Russian, the other type. Where you won stuff. He’d never won anything. That really didn’t seem fair. He remembered the woman he had seen on the TV. The lawyer. She’d talked about fairness. Maybe he should try and get her phone number. He could give her a call. Maybe she could help. Maybe she even wore stockings.

Poor Harry, do you expect me to feel sorry for you?

Jesus, it was Trinny! Harry pulled a pillow over his head and chewed his tongue. He thought he had dumped her and shut her up for good, but somehow she was back. What the hell?

There is no peace, Harry. Not for you and not for me.

No, he understood that. Sunday night hadn’t worked out as it should have and Trinny wasn’t at peace because he hadn’t been able to leave her where he wanted to. There had been too many people. Cars parked around the green, a huge pyre of burning pallets, hot drinks being served from the church and children running everywhere. A stupid bonfire night being held a few days early. In the end he found somewhere nearby. It was quiet and secluded, but at the time he thought it hadn’t been right leaving her in the dark little wood.

Right? The whole thing wasn’t right!

No, but his desire had been uncontrollable. Evil. Not his fault. Which was why he needed to find someone like the girls who had looked after him when he was a kid. The ones who held him close. He had never wanted them. Not like that.

Harry. Let me tell you about the birds and the bees. Something happens when you get older …

Harry ignored Trinny. When you got older you got wiser and when you got wiser you stopped taking the pills. It was then he started to see them. Everywhere. He would catch sight of Trinny at the bus stop. The lovely Carmel serving in Starbucks. Lucy crossing the road and running into college, the naughty girl late for a lecture no doubt. And it wasn’t only those three, it was the others as well: Deborah, Emma and Katya. It was a miracle how they had all appeared. The pills must have hidden them somehow, but they were there all along. Waiting.

Crazy Harry!

Crazy. Sure he was crazy, but he also knew what he was seeing. The trouble was that the girls on the street didn’t look right. Bits of flesh poked out everywhere and they wore make-up. Not good. Not clean. But there was one place he’d worked where the girls knew how to care, how to cuddle, and from the clothes they wore Harry didn’t think they were likely to be dirty either. He began to spot familiar faces there too. He’d go home and look at the old pictures and then he would begin his observations and tests. If the girls were really lucky he might take it one step farther.

Like you did with me?

Yes. He discovered Trinny some months back. She had been the first he had collected and he’d got it a bit wrong. There had been a misunderstanding.

And I was half naked. Was that a misunderstanding?

He wanted a few more pictures, wanted her dressed like he remembered.

Something else as well.

When her clothes slipped off he had seen the curves. He needed to touch them, feel them, stroke them.

Fuck me, more like.

No. That was the last thing he had wanted to do.

But you did.

Yes. Afterwards. When the girl had been quiet. When she had gone through the cleaning process and he knew she hadn’t been right.