Полная версия

The Wolf Within: The Astonishing Evolution of the Wolf into Man’s Best Friend

In a narrow gallery towards the back of the Chauvet cave complex is a tantalising glimpse of another secret of this revolution. Impressed in the soft sediment that forms the floor of the cave are the clear impressions of a child’s footprints. He or she, let us say he, was about eight years old. What he was doing that far back in the pitch-black cavern we can only imagine. From the measurements of his gait he was walking quite normally, not running nor hesitating on his way to the back of the cave. Human footprints of this age are very rare indeed, but it is not the track of the boy that makes this so unusual and important for our story. Alongside the child’s is another, quite different, set of prints. Perfectly preserved in the limey sediment that covers the cave floor, hidden from view and undisturbed for 30,000 years, are the tracks of a fully-grown wolf.

We cannot be sure that the boy and the wolf were walking side by side when they made the tracks or whether the prints were left thousands of years apart. The passage is very narrow at this point and yet the tracks never cross each other, making it more than likely that they were made at the same time. Was the wolf hunting the boy? Or were they exploring the cave together, companions in a great adventure? The footprints hint at a very close relationship, friendship even, between the boy and the wolf.

Or was the animal that trotted comfortably at the boy’s side no longer a wolf, but already on its way to becoming a dog?

* This is the ‘Cave of Forgotten Dreams’ of the chapter title. I have taken the name from Werner Herzog’s excellent 2010 documentary film about Chauvet cave.

8

Hunting with Wolves

The great changes that swept through Europe in the Upper Palaeolithic were products of the refreshed human mind, capable not only of great innovation but also of seeing the world in a different way. An essential element in this process was our ability to learn from observation, to reproduce novelties whenever we saw them. This ability is still with us today, aided by language and other forms of communication. Nowadays new ideas spread around the world almost instantaneously. Even though in the distant past the diffusion of ideas would have been much slower than this, invention and creativity were a characteristic of the time. Whether it be the best way to make an arrowhead or a spear-thrower, or the method of threading beads to make a necklace, or how to make a primitive flute by drilling holes in the wing bone of a swan, all these ideas spread through observation and duplication.

The observant Palaeolithic hunter would have seen wolves in action, relentlessly pursuing their prey until the hunted beast was exhausted, then surrounding it. Unable to inflict a fatal bite through the spinal cord like a lion, the wolf must lunge to inflict flesh wounds until, at last, the animal collapses through loss of blood. It is not a pretty sight as, more often than not, the animal is disembowelled while still alive. More to the point, the endgame is dangerous for the wolves, who risk injury from the last desperate thrashings of their dying prey.

Our ancestors would have witnessed this drawn-out death struggle and realised how easily they could have killed the cornered beast. A spear thrown from a safe distance at an animal held at bay by a wolf pack would be an easy kill. The remarkable stamina of the wolf pack could run down the swiftest prey. By comparison human hunters were no match in the pursuit, but with spears, bows and arrows they could kill even the largest animal cornered by wolves with little risk of injury to themselves.

No doubt at first the final act would seem to the wolves like yet another theft of a kill. Wolves have always been vulnerable to having their kills taken over by more dominant predators. Their ability to rapidly consume, or ‘wolf down’, the nourishing internal organs like the heart and liver, and then to quickly carve off huge chunks of meat using their razor-sharp carnassial teeth, was an ancient adaptation to minimise loss.

In such a situation, it is only a small step for a human hunter to realise how to pacify the wolves. Sharing the carcass is all that is needed. Cooperative hunting is of obvious benefit to both sides, if only the wolves themselves could appreciate the benefit of the deal. This approach would not work with lions or bears, but wolves hunted very much as we did, cooperatively in small groups with each member having a separate role.

There is precious little evidence to support my proposition of a working alliance between man and wolf. It makes a great deal of sense to join forces with a wolf pack in the pursuit of sustenance, so it is a reasonable and attractive speculation, but I freely admit that it is the product of my imagination. I felt nervous about proposing it until I discovered that the great zoologist Konrad Lorenz had already envisaged a similar scenario. In his charming book Man Meets Dog, Lorenz writes a fictional account of cooperative hunting between humans and a pack of jackals, which he saw as the wild ancestor of modern dogs.1 He was mistaken about the jackal, as we now know, but he could equally have chosen the wolf. In 2015, the archaeologist Pat Shipman proposed that a hunting alliance between man and wolf was a major factor contributing to the extinction of the Neanderthals.2

I much prefer this explanation, of hunting cooperation leading to trust, for the origin of ‘domestication’ to the alternatives. Foremost among these, and the one most geneticists seem to prefer (even though I suspect many of them have never seen a wolf), is that wolves became accustomed to human company by hanging around their camps and picking up scraps of food from rubbish tips. As well as being dreary in the extreme, this explanation falls down simply because ‘domestication’ was already well under way by the time humans congregated in large enough settlements to produce sufficient waste to sustain an animal with the appetite of a wolf. Nor does it explain why, of all animals including coyotes, jackals, badgers and bears capable of surviving on refuse, none ever developed a bond of the strength and depth that comes close to matching that between human and wolf – in its modern incarnation, the dog.

Almost nothing remains of human activity on the open plains, so evidence of cooperative hunting is always going to be hard to find. Only in the dank recesses of subterranean caverns can we find physical evidence of our distant ancestry. At Chauvet it is not bones nor teeth but paintings and those enigmatic footprints that are the lens through which we glimpse the lives of our ancestors. Eight hundred kilometres north of Chauvet another river, the Samson, cuts through another limestone gorge, its walls pierced by caves. Here at Goyet, though, there is no need to search for the ancient breath of hidden galleries. The caves are wide open and unlike Chauvet have been occupied by humans, both Neanderthal and modern, for a very long time. Excavations at Goyet began in 1867, three years after the Neanderthal type specimen was excavated in the eponymous valley close to Düsseldorf in Germany.

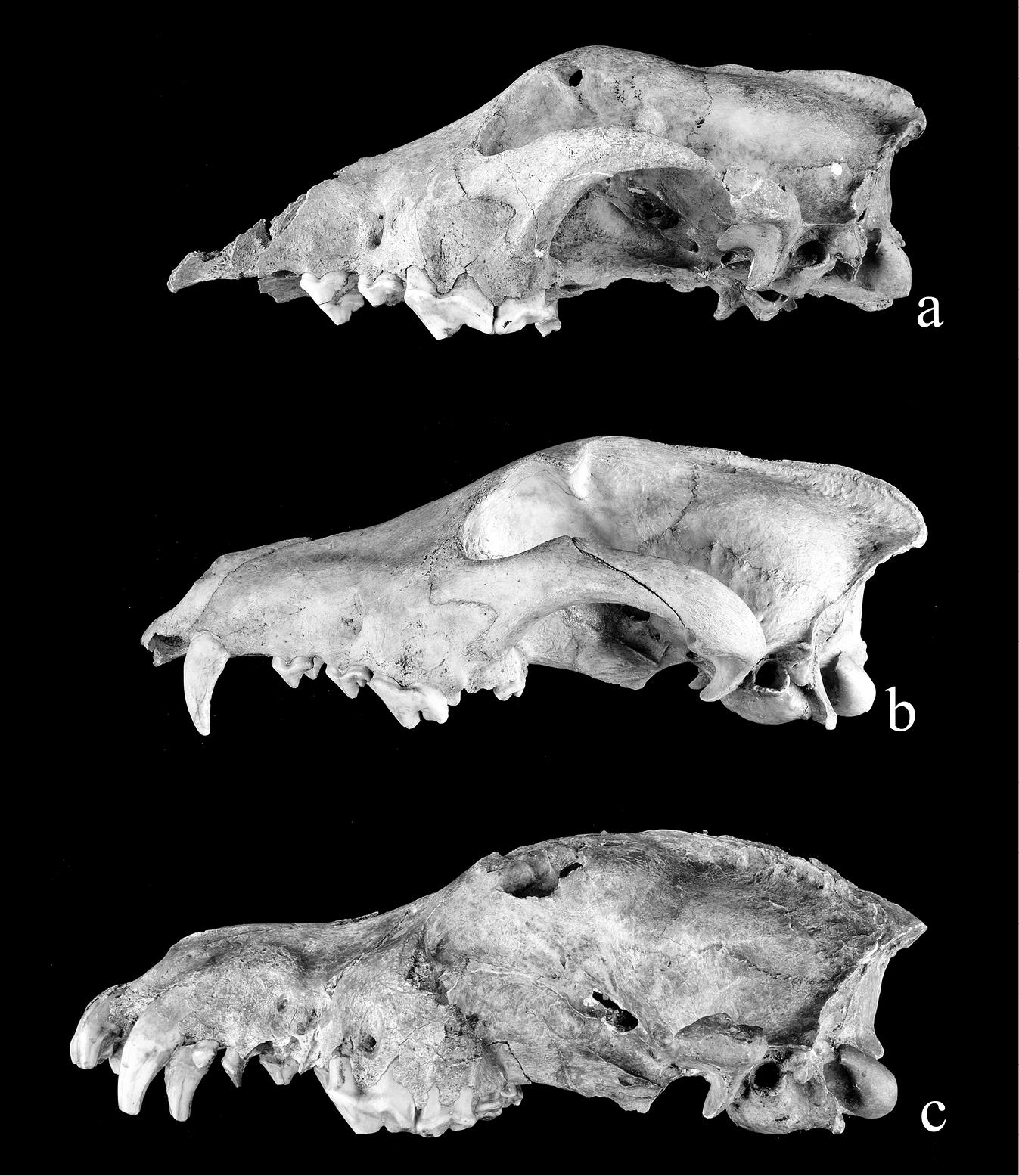

The cave at Goyet contains large numbers of human bones from about 120,000 years BP, including Neanderthals and modern humans along with thousands of artefacts. Our interest is focused on one skull found in a crevice and dated to around 32,000 years BP, in the same age range as the first Chauvet drawings. There is no doubt that it is the skull of a canid, but whether it belonged to a wolf or a dog or something in between is uncertain and, as you might expect, fiercely debated. The snout is certainly shorter than that of a modern wolf, so it shares that characteristic with dogs. Again predictably, and rather like the case of the original Neanderthal skull, which was at first thought to be that of a deformed human, some see it as merely a wolf with a very short nose.

The short snout and wide braincase of a canid skull (a) found in Belgium’s Goyet cave, in comparison with two ancient wolves found in nearby caves (b, c), led scientists to claim that the Goyet skeleton is from a 36,000-year-old dog. This image is reproduced courtesy of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Science and Wilfred Miseur. (The Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Science, Wilfrid Miseur)

If wolves and humans were discovering the mutual advantages of hunting together, perhaps one might expect wolves to feature prominently in the images at Chauvet, Goyet and elsewhere. Yet they are conspicuously absent from these murals. The only wolf-like image from this area is a crude outline from the Dordogne, at Font-de-Gaume, an area rich in limestone caves with a long history of prehistoric human occupation, both Neanderthal and modern. The drawing is among over 200 images of contemporary animals, including the usual suspects like mammoth, bison and woolly rhinoceros, and dates to around 17,000 years BP. Other than this, there are no depictions of wolves at Font-de-Gaume or in any nearby caves. The other notable subject about from these cave paintings is ourselves. There are no images of humans anywhere to be seen. Why not? It is as if the taboo our ancestors felt about creating a human image also extended to the wolf.

I am reminded of Conan Doyle’s short story ‘The Adventure of Silver Blaze’, concerning the theft of a prize racehorse and the murder of its trainer. In solving the crime, Sherlock Holmes explains to Inspector Gregory of Scotland Yard that the dog guarding the stables must have recognised the culprit.

‘Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?’ asks Gregory.

‘To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time,’ replies Holmes.

‘The dog did nothing in the night-time,’ responds Gregory.

‘That was the curious incident,’ replies Holmes.

9

Why Didn’t Shaun Ellis Get Eaten by Wolves?

If there was anything in the notion of an ancient pact between man and wolf that preceded ‘domestication’ then the best way to find out was to meet some wolves.

In my research for this book I had read an account by a man who had managed to forge a great friendship between himself and a pack of wild wolves. Although very far removed from the Upper Palaeolithic when we, I imagined, first began to hunt with wolves, I wondered whether the basic instincts on which that relationship was based would still be there.

Shaun Ellis, the co-author of The Man who Lives with Wolves, describes how, as a young man, he had become instantly entranced by the sight of a captive wolf.1 Shaun’s transforming experience had happened in a wildlife park near Thetford, not far from his childhood home in Norfolk. The brief encounter changed Shaun’s life entirely and led him eventually to devote himself to wolves. He moved to the USA to work as a volunteer at a wolf rehabilitation centre in Idaho and later set out on his own to find and live among a wild wolf pack.

I heard that he had returned from Idaho and, now in his early forties, was living on a farm in Cornwall. I knew I needed to meet Shaun as soon as possible and, if he would allow it, interview him. Fortunately, he agreed, and on a cold and dark Friday in December, my wife Ulla and I set off on the long train journey to Lostwithiel, where Shaun and his partner Kim now live in the company of a small pack of wolves. We settled into the cosy parlour of the farmhouse, at least partially revived with a hot cup of tea.

I began by asking Shaun about his childhood on his grandfather’s farm deep in the Norfolk countryside, leading up to that first encounter with the wolf. An only child, Shaun had been raised mainly by his grandparents, his mother having to work full-time to support the family. His grandfather in particular had been an important influence, fostering Shaun’s growing love of the outdoors. They took frequent walks together with their dogs in the woods and across the fields, hunting rabbits. Always a reluctant pupil, Shaun left school at 15 and had various jobs including a spell in the army.

A free and easy man, his life continued with no definite purpose until the day he took a bus to the local zoo in Thetford. Wandering around, he came upon the wolf enclosure. There, only a few metres away, stood a fully-grown wolf looking straight at him. Here, right in front of him, was the savage killer he had been taught to fear. As he stared back into its golden yellow eyes he felt as though it was touching his very soul. It was as if the creature could read his deepest thoughts and somehow understood him better than any human had ever done. In that instant Shaun’s future path through life was fixed. He has devoted himself ever since to understanding and to helping the rest of us to understand and appreciate what these wonderful creatures are really like. He was, however, sufficiently self-aware to realise that the wolf probably looked at every visitor in the same way.

No matter, over the next years Shaun’s life revolved entirely around wolves. Lacking any professional qualifications and viewed with suspicion by some professional biologists, Shaun has lived with wolves, has brought up a family of wolves, and in the process he felt as though he had almost become a wolf himself. For two years he was alone with a pack of wild wolves in the forests of Idaho. He had travelled to that part of America to work at a wolf education centre where a captive pack was kept in order to educate visitors and to disabuse them of the wolf’s thoroughly undeserved reputation for savagery. After a while Shaun realised that he could never really understand the enigmatic animal only by working with captive wolves, so he packed his rucksack and set off alone into the forest.

Shaun knew there were wolves living there – they migrated every year down from Canada and across Montana into Idaho. But he did not know exactly where they would be. Three months passed before he saw any sign of a wolf. Then, one day, he saw the unmistakable paw print of a large male in the soft mud by the side of a waterhole. In the weeks that followed he heard the chilling chorus of a howling pack drifting through the night.

Eventually he caught a glimpse of his first wolf, a large black male, as it crossed the track some hundred metres ahead. The wolf looked at him briefly before trotting off into the forest. Weeks passed and Shaun saw the black wolf more regularly as if it were sizing him up, whether as a meal or a mere curiosity he could not be certain. A few weeks later, the black wolf reappeared with four others, two males and two females – a real pack. Slowly, day by day, week by week, the wolves became more confident until one day the big male came up to Shaun, sniffed him and suddenly nipped him just below the knee.

Although it was painful, Shaun knew from his experience with captive wolves that this was not a bite in anger. Rather like shaking hands, it was a way for the wolf to introduce himself.

All wolf packs maintain a strict hierarchy. As a rule, only the dominant pair, the alpha male and female, breed, while the other wolves are given supporting roles in the pack. Generally speaking, the other wolves are the siblings and offspring of the alpha pair. Whereas the alpha female is the undisputed leader of the pack, it falls to the beta animals, one rung down in the hierarchy, to maintain discipline and to organise the defence of the pack when it is threatened. It was the beta male, the enforcer, that sized Shaun up and gave him that painful bite, not in anger but as an introduction. The encounters between Shaun and the wolves became more and more frequent over the next weeks. After six weeks he felt that he had been accepted by the pack as an ‘honorary wolf’. He was given the job of what he describes as a diffuser, a calmer of nerves. Like any other family, wolf packs can argue, and they have sharp teeth and claws with which to make a point. Shaun’s role, as he saw it, was to make sure these petty squabbles did not get out of hand.

‘Why,’ I asked him, ‘were you not attacked?’

‘Because I was useful. Also I suspect because the wolves could learn from me, something they needed to do, surrounded as they were by wolf-hating bloodthirsty hunters.’

Shaun’s joy at being accepted by the pack was severely tested one day when, without warning, the beta male suddenly lunged at him and knocked him to the ground. The wolf stood over him, fangs bared, and growling. Here is Shaun’s account of his terrifying experience.

I suddenly felt this was the end. Up to then I had trusted them completely not to harm me, but in that instant I remember thinking OMG they are this creature after all. They are going to kill me. He kept pushing me back with nips and growls into a hollowed-out tree then stood outside snarling. What a fool I’ve been, I thought to myself, they have been biding their time “fattening me up for Christmas” so to speak. But the fatal attack never came. I was there pinned down for an hour and a half then, just as suddenly as the attack had begun the wolf backed off. He called me with a low-pitched whimper and went into a very appeasing body position as if to apologise. It was as if it had suffered some kind of psychosis, turning into a killing machine and then back again.

It took me a while to come out, and that is when he led me down the path to where I was going. There by the stream were the unmistakable marks left behind by a huge bear. Not only did he save my life but the episode reinforced my original belief that I should always trust them.

After that, Shaun spent the remainder of his two years living peacefully with the pack.

Others like Shaun have found themselves strangely attracted to wolves and sought out their wild company. Sometimes they have written about their experiences and their books have become bestsellers. Farley Mowat was one such author.2 Mowat was a government biologist dispatched in the 1960s to the Keewatin Barren Lands of northern Manitoba for eighteen months to report on the falling numbers of caribou and confirm, as was widely thought, that wolves were to blame for this decline.

The shortage of caribou was worrying the powerful hunting lobby that pressured ministers to do something about ‘the Wolf Problem’. The ‘problem’ boiled down to an insistence by hunters, guides and lodge owners that wolves were destroying the big game on which their businesses depended. According to the hunting lobby, it was well known that wolves had an insatiable appetite for killing way beyond the need to feed themselves, although the blatant irony of this conviction was lost on the hunters. Mowat’s mission was to investigate the accusations and report to embattled ministers.

Like Shaun Ellis, it was a long time before Mowat encountered his first wolf. Attracted by what he thought were the pathetic cries of a young dog in distress, he set out to find the source of the whining. In order not to scare what he thought was a wolf cub, he tracked the whelps from behind a gravel ridge. Peering over the crest, he found himself only two metres away from a fully-grown Arctic wolf. For a few seconds each stared into the other’s eyes and Mowat fell under the same hypnotic spell that had entranced Shaun Ellis. The wolf was the first to break free from the spell’s grip. He leaped into the air and, with an effortless trot, vanished into the crepuscular gloom of the Arctic dusk.

In the succeeding weeks, as Mowat got to know the wolves better, he realised that, far from being the active observer, it was he, the human, who was being studied by the wolves. More than once after vainly scanning the horizon in front of him for signs of his ‘quarry’ he would turn around to see two or three wolves resting on the ground a few metres away, just looking at him. Like Shaun Ellis, he was aware of being weighed up by the wolves, but for what purpose he could not be sure.

As spring turned to summer, the tundra was streaked with long lines of caribou sauntering north to their summer territory, and Mowat had a stroke of good luck. From the top of an esker, a gravel ridge deposited by melting ice, he located a den with four young cubs playing outside with no sign of the parents. A curious cub, catching his scent, began to approach when suddenly, and with a piercing howl of alarm and warning, an adult returned. Mowat lost his footing and tumbled down the side of the ridge, ending up in a tangled heap at the bottom. Half expecting the big male, the ‘enforcer’, to clamp his enormous jaws around his throat at any moment, Mowat turned over to look up the slope. He saw not one but three adults standing in line abreast, peering down at him with amused delight. When they had seen enough of this hilarious performance they turned and silently withdrew out of sight.

Later that night, safely back in camp, it dawned on him that all the stories he had been told of wolves as savage and demented killers were completely untrue. Earlier, these animals had the hapless Mowat completely at their mercy and yet they did nothing to threaten him, even though he was close to their own cubs. After this, his view of the mission on which he had been sent changed completely. He lost all fear of the wolves, moved out of the fetid cabin he was occupying and, leaving his guns behind, pitched his tent close to the den.

Over the following months he saw that, while wolves certainly did kill caribou, they only did so at certain times of the year. The rest of the time, for example when the caribou had moved to their own summer feeding grounds in the far north, Mowat was surprised to find that the wolves lived almost entirely on mice, lemmings and ground squirrels supplemented by the occasional pike or lamprey ambushed as they made their way up the narrow channels of the muskeg to spawn.

Many things impressed Mowat about the wolves he lived with that summer. He admired their close and amiable family life, their ingenuity at finding food, and their tolerance of his presence. What impressed him most of all was their ability to communicate with other packs over long distances. One day towards the end of the summer as the first frosts iced the muskeg moss, Ootek, Mowat’s occasional Inuit companion, drew his attention to a barely audible sound on the wind.

‘The caribou are coming,’ he whispered. He had heard the faint cries of a wolf from an adjoining territory announcing the returning migration of the caribou from the north. Ootek gathered up his hunting gear and set off to intercept the herd, returning a few days later loaded down with fresh meat. Ootek related another story from his childhood on the tundra. Following Inuit tradition, when he was five years old his father, a powerful shaman, took the boy to a nearby wolf den and left him there. For twenty-four hours the young Ootek was fed by the wolves and played with the cubs, supervised all the while by one of the adults. Was this a modern example of the same sentiment behind the origin of the twin tracks of adult wolf and human child laid down on the floor of Chauvet cave some 30,000 years earlier?

I could have chosen any number of reports of humans and wolves living in close harmony in the wild. While none of these extends to witnessing the mutual cooperation on a hunt as I have imagined from the European Palaeolithic, the familiarity that the Inuit have with the wolves with whom they share the Barren Lands of Manitoba is a far better guide to understanding how we first grew close to the wolf than any amount of malicious falsehoods about their homicidal savagery.

Eventually Mowat’s sojourn with the wolves came to an end and he returned home. He had found no evidence that the wolves were solely responsible for the fall in caribou numbers. It never made any sense to imagine that they were. After all, wolves had hunted caribou for tens of thousands of years before humans arrived in North America. Far from providing the excuse that his employers and the powerful hunting lobby were searching for to justify the final extermination of the wolf from the whole of North America, his report rather proved the complete opposite. It was filed under ‘For Active Consideration’ and never seen again.