Полная версия

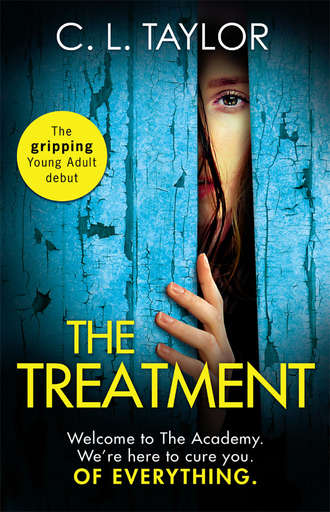

The Treatment: the gripping twist-filled YA thriller from the million copy Sunday Times bestselling author of The Escape

She walks back through the gate into the park without looking back to check if I’m following. Do I go with her? She’s got a strange sense of humour and she’s definitely a bit unhinged but she seems to know something about the RRA and I need to find out what it is. I take off after her, jogging to catch up. By the time I reach her, she’s sitting in the shelter by the large field local schools use as a football pitch. She unzips her jacket, reaches into a pocket and pulls out her phone.

‘Look at this,’ she says.

A video appears on the screen. It’s a guy about our age standing on a skateboard, at the top of a ramp. He is dressed in a long-sleeved T-shirt, a beanie, jeans and trainers. As the camera zooms in on him he flashes the horns symbol with the fingers of his right hand and sticks out his tongue then he pounds the ground with one trainer and he’s off! The skateboard zooms down the ramp across a patch of tarmac and up another ramp. As it reaches the top, he stamps on the back of the skateboard and it flips into the air. For a second he’s separated from it but then he lands firmly, with both feet and zooms back down the ramp.

‘Yeah!’ yells a voice that sounds a lot like Zed’s and then a female hand makes the horns in front of the camera. Clamped between the thumb and fingers is a fat spliff.

‘That’s for me, yeah?’ Skateboard guy approaches the camera, grinning and whips it out of her fingers. He tokes on the joint and blows a stream of smoke up at the sky.

‘How good was I?’ he says as he looks into the camera.

‘Really good,’ Zed says. ‘Really bloody good.’

Skateboard boy leans in towards the camera. His face gets blurrier and blurrier the closer he gets and then the clip stops.

‘That’s when he kissed me,’ Zed says now. Her voice has changed. She sounds softer, more pained.

I don’t get it. What’s that video got to do with the RRA and the Government trying to take down her blog posts. He’s obviously her boyfriend but so what?

‘Come with me.’ She tucks her phone back into her pocket and stands up. ‘I’ve got something else to show you.’

I follow her through the dark park, towards the car park at the far end. The gate is locked so we have to climb over it.

‘Where are we going?’ I ask for the third time since we set off.

‘This is my car.’ Zed taps the bonnet of a red Mini Metro. ‘Passed my test last month. It’s ancient but it runs.’

If she can drive she’s older than me then, by at least a year.

‘Nice,’ I say, then jolt with surprise as I notice the shadowy figure sitting in the passenger seat. Zed sees me jump and rounds the car.

‘Charlie.’ She taps the passenger side window. ‘Come and say hello to my new friend.’

The door opens and I take a step back. I’ve got no idea who’s inside or whether or not I can trust Zed.

Two shiny black shoes appear beneath the open car door as Charlie swings his legs out. He slowly stands up, shuts the door and turns to face Zed. I can tell it’s the same guy I saw in the video, even in the half light, but they couldn’t look more different. He’s wearing neat, beige chinos – the sort Tony wears at the weekend – and a navy V-neck jumper over a white shirt. His hair is closely cropped, short but not Marines short. But it’s not his appearance that makes me shiver. It’s the strange, vacant look in his eyes as his gaze switches from Zed to me.

‘Hello.’ The edges of his lips curl up into a smile. It happens so slowly it’s like watching a robot attempt a grin. As he steps towards me, his right hand extended, I back away.

‘It’s OK,’ Zed says. ‘He’s not going to hurt you. Just shake his hand.’

I stiffly raise my right hand and lock palms with Charlie. He squeezes my hand and pumps my arms up and down once, twice, three times.

‘Did you go to the RRA?’ I ask him when he finally lets go of my hand.

He nods. ‘I did some stupid things and made some stupid decisions. Being at Norton House taught me how foolish I was. I have learnt how to be a better person and how to contribute to society.’

‘Right, I see.’

‘It’s a pleasure to meet you. Any friend of Evie’s is a friend of mine.’

‘Charlie,’ Zed hisses, ‘I told you not to call me that in public. You’re supposed to call me Zed.’

‘But that’s not your real name. Your real name is Evie Elizabeth Bar–’

‘Charlie, get back in the car!’ Zed yanks on his arm and gently shoves him in the direction of the red Mini. When he reaches the passenger door he touches the handle then looks back.

‘Apologies,’ he says, his cold, vacant eyes meeting mine. ‘I didn’t catch your name.’

‘Robin,’ I say. ‘Robin Redbreast.’

I wait for him to laugh or tell me to sod off. Instead he nods, as though Robin Redbreast is a perfectly normal name, and gets into the car.

‘Well?’ Zed says as the passenger door clicks shut. ‘Do you get it? Do you understand why we had to meet? Why you needed to meet Charlie for yourself?’

I glance back at the car. Charlie is watching us from the passenger seat, still smiling in that strange fixed way. I can’t believe he’s the guy from the skatepark. They look alike but it’s as though they’re two completely different people.

‘What’s wrong with him?’ I ask. ‘Is he on drugs?’

Zed laughs dryly. ‘If only. I could stop him from taking them and he’d go back to being the old Charlie again.’

‘So why’s he like this? What happened to him?’

‘They “treated” him.’ She fixes her bright, blue eyes on me. ‘That’s what did this to him. They turned him into this … this …’ She shakes her head. ‘I don’t know what he is. He looks like Charlie, he feels like him and smells like him but his personality’s gone. The Charlie who went to the RRA was a rebel. He was outspoken. He was lively. He kicked back at authority. He –’

‘He sounds a lot like my brother.’

She raises her eyebrows and sighs. ‘That’s what I was worried about. But he won’t be your brother when he gets out. You won’t recognize him. Charlie used to smoke weed, a lot of weed. That’s why he was excluded from three schools. He was caught toking in the school grounds. Now if I ask him if he fancies a smoke he gives me a lecture about the psychotropic effects of marijuana and reels off statistics about heavy users being more prone to schizophrenia, yada yada yada.’

I shrug. ‘Well, that is true.’

‘But it’s not the point. The point is there’s no way Charlie would have given me a lecture like that before he went in. And he definitely wouldn’t have announced that he wants to train to become an accountant. Or agree with his dad that the police should have greater stop and search rights, or suggest that internet usage should be monitored nationwide and —’

‘You think he’s been brainwashed,’ I say, glancing back at the car. ‘Don’t you?’ Charlie is still watching us intently. He’s starting to seriously freak me out.

‘Yeah.’ Zed runs her hands through her hair and stares up at the sky. She inhales sharply through her nose and blinks rapidly but there’s no stopping the tears that well in her eyes. ‘Sorry, sorry.’ She swipes at them with her coat sleeve. ‘I can’t believe I’m crying in front of a complete stranger but you’re the first person I’ve really talked to about this and it’s … it’s just so hard. I’m in love with him. Or at least, I was. I keep waiting to see a glimpse of the old Charlie, for whatever’s happened to him to wear off, but it hasn’t happened. It’s been three months since he left the RRA and …’ Fresh tears replace the ones she wiped. This time she doesn’t try to hide them.

‘Hasn’t anyone else noticed?’ I say. ‘His friends or his parents? If Mason came back like Charlie, Mum would be onto the police straight away.’

‘Would she?’ She laughs dryly. ‘Andy and Julie love the new Charlie. His mum’s always going on about how polite and helpful he is now and how delighted she is that she’s got her little boy back. And Andy can’t stop telling people how well Charlie is doing at school.’

‘But he’s so weird. Sorry.’ I pull a face. ‘I know he’s your boyfriend but he’s … creepy. How can they not see that?’

Zed rubs the back of her neck. ‘I think they see what they want to see – their son doing what he’s told for a change. He doesn’t answer them back; he doesn’t stay out late. He’s perfect, as far as they’re concerned. His dad keeps going on about how proud he is that Charlie’s got his priorities straight at last and how relieved he is that he’s decided on a career instead of claiming he’s going to sign on as soon as he leaves school.’

I groan loudly. Make This Country Great. Contribute to Society. A Safe Land for Hardworking People. All buzzwords of the new Government. I hate that our parents voted them in. It’s our future they’ve screwed up and we don’t even get a say in it.

‘What about Charlie’s friends?’ I ask. ‘Surely they’ve noticed a difference.’

‘Of course. They tried to snap him out of it too but they’ve given up on him now. They think he’s a total killjoy. If he’s bothered by the fact they don’t call or message him any more he doesn’t show it. In fact, he’s really sniffy about the whole skate scene now. He acts like he’s really superior to everyone. If I remind him what he used to be like he says, “I was a waste of space, Evie. I’m just lucky I was given the opportunity to turn my life around.”’

It’s doing my head in, everything that Zed is telling me. I feel like my brain is melting. The RRA woman Mum spoke to on the phone told her that Mason had just been moved to pre-treatment. That means he could be ‘treated’ at any time. For all I know it could be tomorrow. Or he might be there already. I can’t let them do to him what they did to Charlie. I just can’t.

‘Zed,’ I say softly, as I angle her away from Charlie’s strange, staring gaze. ‘I’m going to need your help.’

Chapter Eight

I have to wait until morning break before I can use the school library. I head for the bookshelves first, filling my arms with as many psychology books as I can find that cover brainwashing, mind control, behavioural issues and therapeutic practices. A lot of them look a bit too basic but I haven’t got time to go to the library in town. As soon as Mum and Tony find out what I’m planning they won’t let me out of their sight. When I’ve got all the books I need I log onto one of the school computers. We’ve only got one printer at home and it’s in Tony’s office. I can connect to it from my laptop but I can’t risk him discovering what I’m up to. Last night Zed told me everything she knows about the RRA, including where it is. It’s a large Victorian mansion called Norton House, formerly a psychiatric hospital, on the Northumberland coast. The sea is on one side and acres and acres of countryside are on the other. It’s remote and you can only reach it by car or boat. Zed reckons it would take at least an hour and a half in a taxi to get there from Newcastle upon Tyne train station.

I found out some interesting things about Norton House when I was Googling last night. Very interesting inde–

‘What’s this?’ A hand snatches my computer printout as I reach for it. Lacey. What the hell is she doing in the library? She never comes in here, ever. She must’ve been looking for me. I glance around, looking for her sheep. They can’t ambush me here, not when Mrs Wilson the librarian is sitting at her desk and there’s at least half a dozen kids milling about. But there’s no sign of her little flock. Lacey is totally alone.

‘You’re not the only one who is allowed to use the library, Drew,’ she says as though she’s read my thoughts. ‘I need to finish my English course work and –’ She peers at the printout in her hand. ‘What’s this? I didn’t know you did design and technology.’

I try to snatch it back but she whips it away and holds it high above my head. Mrs Wilson glances over, disturbed by the noise.

‘Sorry!’ Lacey giggles, as she presses a finger to her lips. ‘We’ll try and keep it down. Won’t we, Andrew?’

Mrs Wilson looks away again, reassured by Lacey’s fake smile and her stupid, sing-song voice.

‘Lacey,’ I say quietly. ‘Just give it back to me.’

She shakes her head. ‘Not until you tell me what it is.’

‘Don’t do this. Not now.’

‘Why not?’

I take a deep breath in through my nose and exhale heavily. I need to keep calm. I swivel round in my chair and press Control P on the keyboard. If Lacey won’t give me my map back I’ll print out another one.

‘What are you up to, Andrew?’ Lacey presses her body up against mine as she peers at the screen. The printer beside me makes a chugging noise and I reach out a hand to grab the second printout. But it’s not the paper Lacey’s interested in. Click, click. She grabs the mouse and swaps one tab for the next. The first website I was looking at flashes up on the screen.

‘Oh my God,’ she breathes. ‘It’s that reform academy that Aoife and Freya Rotheram were sent to. The one up north. Didn’t your brother get sent there too?’

‘Lacey, go away.’ I grab the printout with one hand and shove her away from me with the other.

‘Oh my God!’ Her jaw drops as she stares at me. ‘I know what you’re doing. I know what the printout is. It’s a map. It’s some kind of tunnel system under the school. You’re going to try and help your brother break out. Hey, Mrs Wilson, did you know that —’

‘No!’ My chair crashes to the floor as I stand up quickly. She can’t do this.

‘Lacey.’ I keep my voice down as I step towards her. ‘You don’t know what you’re talking about.’

‘Don’t I?’ Her blue eyes glitter as she smiles at me. ‘Why are you freaking out then?’

The room has fallen completely silent. Everyone is watching us. They’re waiting to see how this plays out.

‘Lacey,’ I say. ‘Don’t go there.’

‘You threatening me, Andrew?’ Her top lip tightens into a sneer. I used to think Lacey was beautiful, the prettiest girl in our year with her long, shiny black hair and her bright blue eyes but I’ve never seen anyone as ugly as the girl standing in front of me now.

‘Girls!’ Miss Wilson stands up and places her hands on her desk. ‘Is everything OK?’

‘If you tell her,’ I hiss, ‘I’ll tell Jake Stone to drop you.’

Her eyebrows shoot up in alarm. ‘How do you know about Jake?’

‘I know about everything.’

‘Liar. You’ve been eavesdropping, you little troll. Anyway, Jake wouldn’t listen to you. No one listens to you. Even your own parents think you’re a drama queen. What was it your dad said in mediation? Drew can be a little highly strung.’

‘Tony’s not my dad.’

‘Girls!’ Miss Wilson rams her desk and crosses the library towards us. A couple more strides and she’ll be able to hear every word we’re saying.

Lacey flicks her hair away from her face. ‘My mistake, Drew. Your real dad was a nut job, like you. Maybe you should kill yourself like he did.’

Before I know what I’m doing my clenched fist arcs through the air and smashes against Lacey’s cheekbone. There’s a terrible crunching sound, of bone on bone, then she stumbles backwards. She falls, as though in slow motion, one hand reaching for me, the other curling towards her face. Smash! The back of her head smacks against library carpet. Her body jolts and then lies still. There’s a hand on my shoulder, shoving me out of the way and Mrs Wilson screeches for someone to call the nurse. I stand stock still as she crouches down beside Lacey’s crumpled body and touches her hands to the side of her face.

‘Lacey!’ she calls. ‘Lacey? Can you open your eyes?’

But Lacey doesn’t open her eyes. She lies completely still. As still as the dead.

Chapter Nine

‘We came as soon as we could,’ Mum bursts into the headmaster’s office with Tony close beside her.

‘Drew! Oh my God.’ She skirts across the room and drops to her knees beside me. ‘Drew!’ She gathers me into her arms and repeatedly strokes the back of my head. ‘Oh my God, Drew. What happened?’ She holds me at arm’s length and stares into my face. ‘Please tell me it’s not true. Please tell me you didn’t hit Lacey Mitchell.’

‘Jane.’ Tony touches her arm and nods his head towards Mr Mooney, sitting across the desk from us. ‘Let Layton deal with this.’

‘Yes, yes, of course.’ Mum runs her fingers through her hair as she sits down in the plastic chair between me and Tony. Her forehead is damp with sweat and her eye make-up is smudged. I feel sick, knowing how much this must be upsetting her and I wish there was something I could do to make her feel better but there’s nothing I can say, not with Tony and Mr Mooney sitting so close.

‘Mr and Mrs Coleman.’ Mr Mooney gives them a sharp nod. ‘Thank you so much for getting here so quickly. I know how busy you both are, particularly you, Mr Coleman.’

He gives Tony a deferential smile that makes me cringe. Big suck up. He’s got the National Head of Academies in his office and he’s not going to put a foot wrong. We all know Tony could get him sacked in a heartbeat if he wanted to.

‘No problem, George,’ Tony says, giving him a condescending smile. ‘We are as concerned as you are about Drew’s behaviour.’

‘Indeed.’ Mr Mooney puts his elbows on the desk and fixes me with an intense stare. ‘Fortunately Lacey is going to be OK. She was only unconscious for a couple of seconds and I’ve heard back from Ms Wilson who accompanied her to A & E that her cheekbone isn’t fractured, although she is still in quite a lot of pain.’

Good. I clench my hands so my fingernails dig into my palms. I’m glad she’s in pain. People can say what they like about me but no one gets to talk about my dad like that.

‘Now the thing is,’ Mr Mooney continues, ‘there’s obviously been a few issues between Lacey and Drew over the last couple of months and we’ve done everything we can to try and resolve them.’

‘Obviously not enough,’ Mum says, ‘or my daughter wouldn’t have done what she did.’

I shoot her a grateful look. She meets my gaze but her eyes are steely.

‘That’s not to say I condone her behaviour,’ Mum says, looking back at Mr Mooney. ‘But something needs to be done.’

‘Well, obviously Drew will be excluded for several days as …’

Several days? He can’t mean that. Surely I should be permanently excluded for punching another student in the face! I didn’t plan on hitting Lacey. I was going to shove a load of PE kits down the toilets and flush the chains to cause a flood, then hit the fire alarm button. And if that wasn’t enough to get me permanently excluded I would have done something worse.

‘… obviously there are extenuating circumstances here,’ Mr Mooney drones on. ‘Then, when both girls are back in school we will restart mediation and –’

‘I’m not going to any more mediation sessions,’ I say.

‘Drew!’ Mum clutches my arm. ‘Don’t be ridiculous.’

‘Don’t pander to her, Jane,’ Tony says. ‘It’s what she wants. I’ve never seen such blatant attention-seeking behaviour.’

My stepdad’s knuckles are white from gripping the arms of his chair so tightly. He wants to have a massive go at me but he won’t do it here, in front of Mum and Mr Mooney. If there’s one thing he can’t stand it’s being embarrassed in public. That’s why he packed Mason off to Norton House because his behaviour didn’t reflect well on him.

Mr Mooney takes a sip of water from the glass on his desk, then sets it back down again. He’s waiting for them to stop bickering.

‘I’m not pandering to her, Tony,’ Mum says. ‘I’m trying to make her see sense.’

‘Look.’ Mr Mooney splays his hands wide on the desk. The tip of his little finger nudges the glass of water ever so slightly closer to me. ‘No one’s going to force you to go to mediation, Drew. Once you and Lacey are back at school we will ensure that any teachers you have for the same lessons are aware of the situation. We will also make sure you’re separated at break and lunchtimes. Once you feel ready to start mediation again we can –’

‘I told you.’ I launch myself out of my chair and stand up. ‘I’m NOT GOING TO MEDIATION!’

‘Drew!’ Tony grips my wrist, his face puce. ‘What the hell is wrong with you?’

‘Drew!’ Mum says. ‘Sit down.’

‘Drew Finch.’ Mr Mooney stands up too. He glares at me from across the desk. ‘You need to calm down.’

‘No.’ I yank my wrist out of Tony’s grip and, before anyone can stop me, I grab hold of the glass on the desk and hurl the water straight into my headmaster’s shocked face.

Chapter Ten

The train guard reaches for the tickets in Mum’s hand, scribbles on them and then hands them back. Mum sighs as she tucks them back into her purse then hugs her handbag to her chest as she stares out of the window. She’s barely said a word to me all day and it’s breaking my heart, seeing her so upset, but what can I do? I can’t tell her that I deliberately threw the water in Mr Mooney’s face because I knew it would make Tony go off the deep end. Or explain why I refused to apologize (because I knew it would deepen my stepdad’s embarrassment) and didn’t put up a fight when he announced that ‘maybe a stay at the Residential Reform Academy would teach her how to behave appropriately’. When we got home Mum came into my room and begged me to talk to Tony.

‘You have to explain to him, Drew. You need to let him know how much the bullying and Mason being sent away has upset you. I’m sure he will listen once he’s calmed down. Mr Mooney was only going to exclude you for three days. You can still put this right, Drew. Please, sweetheart. If you won’t do this for me, do it for your dad. He was always so proud of you. It would break his heart to see you like this.’

I started to cry then. Partly because she was talking about my dad in the past tense (he’s not dead, he didn’t abandon his car at Beachy Head and walk off the cliff. He’s alive and he’s missing. Why doesn’t anyone else believe that?). And partly because I knew it was her heart that was breaking.

‘I know,’ she said as she put her arms around me, ‘that this hard girl stuff is all an act. You’re still my baby, Drew. You’re still my sweet, sensitive little girl. Let’s go down and talk to Tony together. He’s not a monster. He just wants what’s best for you, what’s best for all of us.’

I stopped crying when she said that. Is that why he sent my brother away to be brainwashed, because it was the best for all of us? No. It was best for him.

‘Please, darling,’ Mum begged as she tried and failed to take hold my hand. ‘Please.’

After half an hour pleading and cajoling she eventually gave up.

‘You’d better pack your bags then,’ she said as she hovered at my bedroom door. ‘You’re going tomorrow. Tony’s been on the phone to the RRA. They’ve found you a bed.’

I barely slept last night. I stayed up until 1 a.m. reading my psychology books and studying the printout I printed off the Internet. My hands shook as I turned the pages. I had – have – no idea what I’m letting myself in for. What if I’m locked up the second I get there and I’m shackled to a bed and wheeled into some kind of treatment room? What if it’s not some kind of psychological brainwashing at all? What if electroshock treatment is involved, or an operation? Charlie certainly acted like he’d had some part of his brain removed. I tried to push the thought out of my head and think logically. This isn’t A Clockwork Orange or One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. It’s real life. A real school. An academy for God’s sake. There is no way they can get away with performing operations on kids without the parents’ consent. If they are brainwashing kids they have to be doing it legally. But how? After I put down my book and turned out my bedside light, I felt a fresh flicker of fear. Who did I think I was – charging in there expecting to be able to save my brother? I wasn’t a trained psychologist or an SAS soldier. I was a sixteen-year-old girl. And I was all alone.

‘You know you can’t bring that in with you, don’t you?’ Mum says now, gesturing at the book in my hands. ‘No books, no mobile phones, no games consoles, no music players. Just toiletries and the items of clothing on the printout I gave you.’