Полная версия

The Strangest Family: The Private Lives of George III, Queen Charlotte and the Hanoverians

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by William Collins 2014

Copyright © Janice Hadlow 2014

Janice Hadlow asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Cover image: Queen Charlotte, 1779 (oil on canvas) by West, Benjamin (1738–1820)/Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2015/Bridgeman Images

Source ISBN: 9780007165193

Ebook Edition © August 2014 ISBN: 9780008102203

Version: 2015-06-29

Frontispiece

George III, Queen Charlotte and six princesses (watercolour, attributed to William Rought)

Dedication

FOR MARTIN, ALEXANDER AND LOUIS,

AND FOR MY PARENTS, WHO DID NOT LIVE TO READ IT

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Frontispiece

Dedication

Author’s Note

Epigraphs

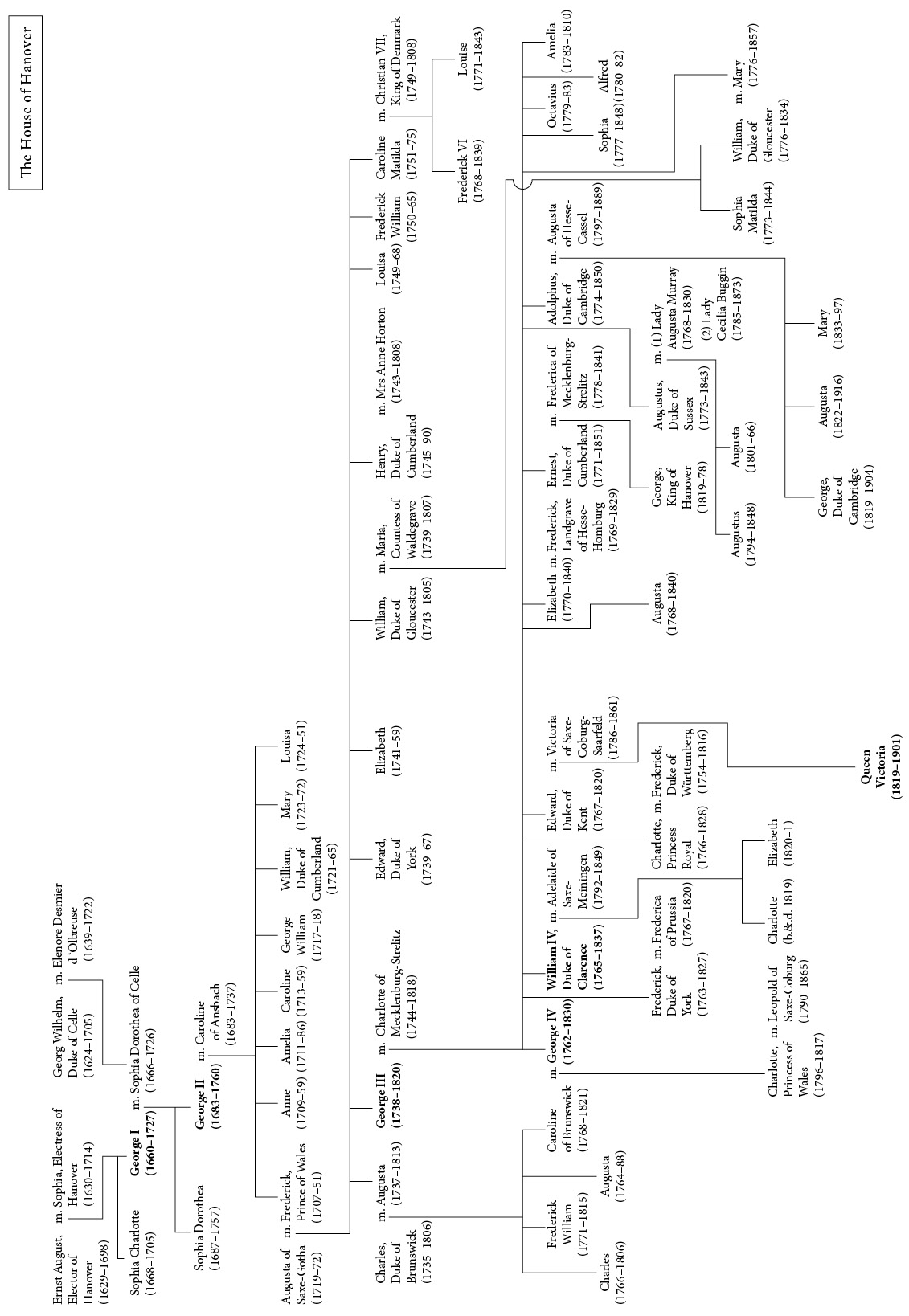

Family Tree

Prologue

1 The Strangest Family

2 A Passionate Partnership

3 Son and Heir

4 The Right Wife

5 A Modern Marriage

6 Fruitful

7 Private Lives

8 A Sentimental Education

9 Numberless Trials

10 Great Expectations

11 An Intellectual Malady

12 Three Weddings

13 The Wrong Lovers

14 Established

Notes

Picture Section

Illustration Credits

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Author

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

WHEN QUEEN CHARLOTTE WAS ASKED by the artist, botanist and diarist Mrs Delany why she had appointed the writer Fanny Burney to the post of assistant dresser in her household, she answered with characteristic clarity: ‘I was led to think of Miss Burney first by her books, then by seeing her, then by hearing how much she was loved by her friends, but chiefly by her friendship for you.’ If questioned about why I wrote this book, I am not sure I could answer with such confident precision. In one sense, it simply crept up on me, emerging from a long love affair with the period and the people who lived in it.

I have always been fascinated by history. I studied it at university, where I was taught by some exceptional and inspiring teachers. As a television producer, I have made many history programmes, covering all aspects of the past – from the ancient world to times within living memory. I have worked with some of the most eminent British historians, witnessing at first-hand their knowledge and passion for a huge variety of subject areas. But it was always the eighteenth century that had first place in my heart. I had immersed myself in the politics of the period at college, but its appeal went far beyond what my reading delivered for me. Like so many others, I was drawn to it partly by the wonderful things made in it: the incomparable architecture that created austerely elegant palaces for the great, and airy, comfortable homes for the ‘middling sort’. I coveted the objects that went into these houses, from the sturdily beautiful furniture to the delicate blue-and-white coffee cups intended to sit proudly on all those much-polished tea tables. I admired the art of the period too, especially the portraiture, whether it was the clear-eyed intensity of Allan Ramsay, the bravura gestures of Joshua Reynolds, or the tender luminosity of Thomas Gainsborough. Those eighteenth-century men and women rich enough to afford it never tired of having themselves painted. If I had been one of them, I would have chosen Thomas Lawrence for my portrait. Who wouldn’t want to see themselves through Lawrence’s humane yet flattering eye, which infused even the most unpromising sitter with a sense of spirit and passion? I would have worn a red velvet dress, as both princesses Caroline and Sophia did when they sat for Lawrence, and hoped for a similarly impressive result: both women gaze directly out from their pictures, proud, commanding and smoulderingly bold. The portraits do not quite capture their true characters, at least as revealed in their letters; but what an image to look upon when your spirits needed a boost.

But much as I responded to the things the period produced, my real desire was to understand the people who lived in it. It was the men and women of what is often called the long eighteenth century – which runs from the accession of George I in 1714 to the death of George IV in 1830 – who really captivated me. Caught between the religious intensity of the seventeenth century and the earnest high-mindedness of the Victorians, this was a society in which I felt very much at home. I enjoyed its bustle and energy, and liked being in the company of its garrulous, argumentative and emotional inhabitants. The contradictions of their world intrigued me. On the one hand, they loved order, politeness, restraint. On the other, they were loud, forthright and often violent. The sedate drawing rooms of the rich looked out onto streets where passions could and did run very high. The poor, in both town and country, had a tough time of it, although they too seem to have shared something of the assertive confidence of the wealthy. For most of the middling sort, however, and especially for the rich, there was good reason to be bullish. This was a period in which there was money to be made, and a new kind of life to be lived. It is the experiences of these people – those who built the houses, big and small, laid out the gardens, commissioned the pictures, bought the furniture – that I have come to know best.

I knew them first by their books, and above all, through the work of Jane Austen. My earliest encounters with the authentic voice of the time came through her novels; the first eighteenth-century people I felt I really knew were the Bennetts of Longbourn, the Elliots of Kellynch Hall, Admiral and Mrs Croft, Mr Elton and his dreadful wife.

From fiction, it was a short jump to the world of real people. I think I began with James Boswell’s London Journal. That was my introduction to the vast and compelling world of eighteenth-century diaries and correspondence in which I have been happily immersed ever since. There are two reasons why I love nothing better than a collection of letters or a lengthy journal. Firstly, I’m gripped by the unfolding human story they capture, the narrative of real life as it is actually lived, the biggest events pressed hard up against the small details of the everyday round, matters of love and marriage, birth and death interspersed with accounts of dinner parties and shopping trips, the ups and downs of relationships, the likes and dislikes, triumphs and failures that are the stuff of all human experience. I always want to know what happened next, how things turned out. Did the marriage for which everyone had planned and schemed take place? Was it a success? Did the baby that seemed so sickly survive? Did the business venture prosper? Was a husband ever found for the awkward youngest sister, or a profession for the lacklustre youngest son?

Secondly, I so enjoy the way the letter- and diary-writers tell their stories. The eighteenth-century voice, in its most formal mode, can be stately and remote; but in more relaxed correspondence, the prevailing tone is quite different. Letters between family and friends have an immediacy and a directness that rarely fail to engage the reader. Educated eighteenth-century writers were extremely candid: there were few subjects that they considered off limits. They were intensely interested in themselves and their own concerns, thinking nothing of filling page after page with detailed analyses of their health, their thoughts, and the nature of their relationships, marital, professional or political. They were tremendous gossips. Some of them were also very funny, caustic, satiric, masters (and mistresses) of an ironic tone that feels very modern in its knowingness and is still able to raise a smile after so many years.

It is very easy, reading their letters, to feel that the people who wrote them are just like us. For me, that is part of the appeal of the period, and it is, to some extent, true. But in other ways, the reality of their lives is almost impossible for contemporary readers to appreciate. In the midst of a world that seems so sophisticated and so recognisable, eighteenth-century people encountered on a daily basis experiences which would horrify a modern sensibility. Outside the well-managed homes of the better-off, extremes of poverty and the brutal and degrading treatment of the powerless and vulnerable were everywhere to be found. Even the richest families lived with the constant spectre of sickness, pain and death and could not protect themselves against the disease that decimated a nursery, the accident that felled a promising young man or the complications that killed a mother in childbirth. There is a drumbeat of darkness in all the correspondence of this period that makes a modern reader pause to give thanks for penicillin and anaesthesia.

Many of the letter-writers who so assiduously chronicled the ebb and flow of family life were women. Then, as is perhaps still the case now, it was women who worked hardest to cement the social relationships that held scattered families and friends together. One of the ways they did this was by writing to everyone in their social circle, passing on news, advice and scandal, describing their feelings and speculating on the motives and emotions of those around them. This sprawling world of the family, especially the lives of women and children, is the territory I have always found most compelling. I am fascinated by the inner life of this intimate place and am endlessly curious about how it worked. I always want to find out who was happy and who was not, how duty was balanced with self-interest, and how power worked across the generations.

It was via these paths that I eventually came to fix upon the grandest family of them all as a suitable subject for a book. I had always been interested in George III, that much-misunderstood man, in whom apparently contradictory characteristics were so often combined: good-natured but obstinate, kind but severe, humane but unforgiving, stolid but with the occasional ability to deliver an unexpectedly sharp and penetrating insight. At first, however, it was the story of his wife and daughters that most attracted me. Queen Charlotte’s reputation was, both in her own time and afterwards, equivocal at best. In her lifetime, she endured a very bad press, excoriated by her critics as a plain, bad-tempered harridan, miserly and avaricious, interested principally in the preservation of rigid court etiquette and the taking of copious amounts of snuff. The real story, as her letters and the diaries and correspondence of those around her reveal, was rather different. Charlotte was never easy to love or, in later life, to live with, but she had a great deal to bear. She was a very clever woman in an age that found clever woman unsettling. Her intellectual appetite was unequalled by any of her successors, but could never be expressed in a way that threatened established expectations about how queens were supposed to behave. She spent nearly twenty years of her life in a state of almost constant pregnancy. In public she embraced this as the destiny of a royal wife; but, as her private correspondence makes clear, she resented the decades spent in child-bearing. Before it was crushed by the horror of the king’s illness, from which she never really recovered, and the pressures of her public role, which she sometimes found almost impossible to endure, her personality was much more attractive, sprightly, humorous and playful.

The lives of her six daughters seemed to contemporaries to contain little of interest except for the occasional whiff of scandal. They lingered unmarried for so long that they were described even by their own niece as ‘a parcel of old maids’. Their narrative is perhaps more familiar now – they were the subject of a group biography by Flora Fraser in 2004 – and it is clear that beneath the apparently bland uneventfulness of their existence, the princesses too were subject to strong emotions which were often expressed in circumstances of great personal drama. Their lives were dominated by their struggles to balance what they saw as their duty to their parents with some degree of self-determination and freedom to make their own choices. Where did the obligations they owed to their mother and father end? When – if ever – might they be allowed to follow their own desire for love and happiness? These contests were largely fought out in the secluded privacy of home – ‘the nunnery’ as one of the princesses bitterly described it – which perhaps made the sisters’ trials less visible than those of their more flamboyant brothers, but they were no less the product of powerful and often disruptive feelings.

These were extraordinary stories in themselves, and ones I longed to tell. But the more I read, the more I was convinced that the experiences of the female royals could really be appreciated only as part of a much wider canvas. The experiences of Charlotte and indeed all her children – the sons as much as the daughters – could not be understood without exploring the personality, expectations and ambitions of the king. It was George III, both as father and monarch, who established the framework and set the emotional temperature for all the relationships within the royal family. And, as I soon discovered, his ideas about how he wanted his family to work, and what he thought could be achieved if his vision were to succeed, went far beyond the happiness he hoped it would bring to his private world.

George was unlike nearly all his Hanoverian predecessors in his desire for a quiet domestic life. As a young man, he yearned for his own version of the family life he thought so many of his subjects enjoyed: an emotionally fulfilling, mutually satisfying partnership between husband and wife, and respectful but affectionate relations with their children. This was an ideal that suited his dutiful, faithful character, and which he genuinely hoped would make him and his relatives happy. But he also hoped that by changing the way the royal family lived, by turning his back on the tradition of adultery, bad faith and rancour that he believed had marked the private lives of his predecessors, he could reform the very idea of kingship itself. The values he and his wife and children embraced in private would become those which defined the monarchy’s public role. Their good behaviour would give the institution meaning and purpose, connecting it with the hopes, aspirations and expectations of the people they ruled. The benefits he hoped he and his family would enjoy as individuals by living a happy, calm and rational family life would be mirrored by a similarly positive impact on the national imagination. In his thinking about his family, for the king, the personal was always inextricably linked to the political.

As I hope this book shows, there were many good things that emerged from George’s genuinely benign intentions. But, as will also be seen, his vision imposed on his family a host of new obligations and pressures. George, Charlotte and their children were the first generation of royals to be faced with the task of attempting to live a truly private life on the public stage, of reconciling the values of domesticity with the requirements of a crown. The book’s title, The Strangest Family, partly reflects the opinions of close observers and indeed of family members themselves that among the royals were to be found some very distinctive, strong-willed and colourful characters; but it also recognises the paradox at the heart of modern monarchy. For most people, the family represents the most intimate and personal of spheres. For royalty, it is also the defining aspect of their public identity. The modern idea of monarchy owes far more to George III and his conception of the royal role than is often realised. His insight did much to ensure the survival of the Crown, linking it to the hearts and minds of the British in ways of which he would surely have approved. But, in other respects, his descendants still find themselves trying to square the circle he created, attempting to enjoy a family life defined by private virtues, yet obliged to do so in the unflinching glare of public scrutiny.

Although the experiences of George, Charlotte and their children are at the heart of this book, I have ranged beyond their stories to include those of their immediate forebears. It is impossible to appreciate what George III was attempting to achieve without understanding the moral world he sought so decisively to reject. In doing so, I was fascinated by the complicated marriage of George II and his wife Caroline (another clever Hanoverian queen), a stormy relationship coloured by passion, jealousy and deceit in fairly equal measure. Their hatred for their eldest son Frederick, operatic in its intensity, still makes shocking reading after so many years. I have also looked forward in time to include in some detail the story of George III’s only legitimate grandchild, Princess Charlotte. Hers is a sensibility very different from that of her predecessors: she was a young woman of romantic inclination, devoted to the works of Lord Byron and given to flirtations with unsuitable officers. The clash of wills between the young Charlotte and her grandmother, the queen, is one in which two very different interpretations of royal, and indeed female, duty collide, with an outcome as unexpected as it is touching.

I did not set out to write a book that ranged so far across the generations and included so many large and powerful personalities. I believe, however, that without that level of scale and ambition, it would be impossible to do justice to the story I wanted to tell. Besides, I have always loved a family saga. That is the narrative that dominates the diaries and correspondence that have been my window onto the reality of eighteenth-century lives. I have tried to use those sources to let the characters in this book speak, as far as possible, for themselves. I like it best when their voices are heard as clearly and as directly as possible. It will be up to the reader to decide if I have succeeded.

Bath, July 2014

Epigraphs

‘But it is a very strange family, at least the children – sons and daughters’

SYLVESTER DOUGLAS, Lord Glenbervie, diarist

‘No family was ever composed of such odd people, I believe, as they all draw different ways, and there have happened such extraordinary things, that in any other family, public or private, are never heard of before’

PRINCESS CHARLOTTE, daughter of George IV

‘Laughing, [she] added that she knew but one family that was more odd, and she would not name that family for the world’

PRINCESS AUGUSTA, mother of George III

Prologue

FORTY-FOUR YEARS AFTER THE EVENT took place that altered his life for ever, George III could still recall with forensic clarity exactly how it happened. On Saturday 25 October 1760, he had set off from his house in Kew to travel to London. He had not gone far when he was stopped by a man he did not recognise, who pulled a note out of his pocket and handed it to him. It was, George remembered, ‘a piece of coarse, white-brown paper, with the name Schroeder written on it, and nothing more’. He knew instantly what this terse and grubby communication signified. It was sent by a German servant of his elderly grandfather, George II; using ‘a private mark agreed between them’, it informed the young man that the old king was dying, and that he should prepare to inherit the crown.1

To avoid raising alarm, George warned his entourage to say nothing about what had passed, and began to gallop back to Kew. Before he reached home, a second messenger approached him, bearing a letter from his aunt Amelia, the old king’s spinster daughter. With blunt punctiliousness, she had addressed it ‘To His Majesty’; George did not need to open it to understand that his grandfather was dead and that he had come into his inheritance. Amelia was probably the first person to call him by the title he would now bear for the rest of his life. With a similarly precise observation of the formalities, he signed his reply to her ‘GR’ – Georgius Rex. When he had set out for London that morning, he was the Prince of Wales, a young man of twenty-two embarking on a day of ordinary business, with no reason to suppose the life of perpetual anticipation and apprehension which he had endured since childhood was about to come to an end. The message contained in that ‘coarse, white-brown paper’ changed all that, turning him into the ruler of one of the most powerful nations in the world. ‘A most extraordinary thing is just happened to me,’ he scribbled breathlessly in a letter he wrote immediately after receiving the news.2 He was right. His long apprenticeship was over. He was king at last, and the mission for which he had been preparing himself for so many years could now begin in earnest.

*

The prospects for the new reign looked exceptionally bright. ‘No British monarch,’ the diarist Horace Walpole later declared, ‘has ascended the throne with so many advantages as George III.’3 The new king was very fortunate in his timing. Had his predecessor died just a few years earlier, Walpole’s bullish optimism would have been inconceivable. Since the mid-1750s, Britain had been embroiled in a territorial struggle between the monarchies of Europe which, by 1756, had metamorphosed into a conflict of international proportions. During the Seven Years War, in North America, the Caribbean and India, the British fought the French in a clash of would-be global superpowers to establish strategic mastery over whole continents. Things started badly for the British, but with the appointment of the buccaneering William Pitt as first (later known as ‘prime’) minister in 1757, the tide was decisively turned. In the course of a year, the French surrendered valuable sugar-producing islands in the West Indies, lost the Battle of Quebec, which challenged their cherished pre-eminence in Canada, and saw their fleet decisively beaten by the Royal Navy at Quiberon Bay. It was hardly surprising that 1759 became known as ‘the year of victories’. As news of fresh triumphs continued to roll in, even the British themselves seemed somewhat taken aback by the scale and speed of their achievement. When the French capitulated at Pondicherry in 1761, which effectively forced them out of India, Walpole was not sure he could absorb any more success. ‘I don’t know how the Romans did, but I cannot support two victories every week.’4