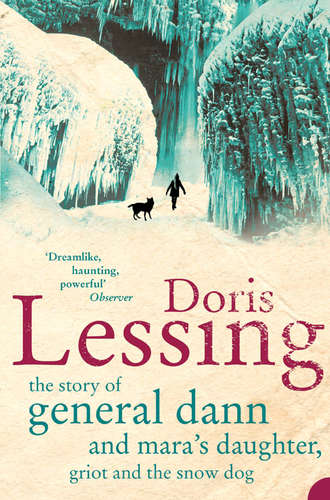

The Story of General Dann and Mara's Daughter, Griot and the Snow Dog

Полная версия

The Story of General Dann and Mara's Daughter, Griot and the Snow Dog

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2018

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу