Полная версия

The Secret of Happy Children: A guide for parents

Because of this, our children may live in a situation where day-to-day messages are fairly vague and indirect: ‘Now don’t do that, darling, come along’, ‘There’s a good boy’. Both positive and negative messages are casual and not great in their impact.

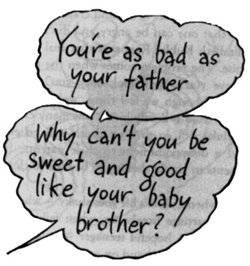

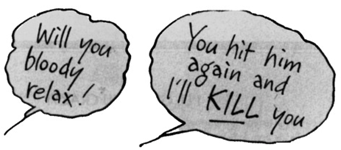

Then, one day, when life has really overloaded Mum or Dad, there comes a powerful outburst, ‘You little brat, I wish you’d shut up’, anchored with wild eyes, sudden, close proximity, never-before-heard volume and a sense of quivering lack of control that is quite unforgettable. The message is inescapable, although untrue: this is what Mum or Dad really thinks of me!

The words that overwrought parents choose at these times can be remarkably strong.

‘I wish you’d never been born.’

‘You’re a stupid, stupid child.’

‘You’re killing me, do you hear?’

‘I’d like to throttle you!’

It’s not bad to get angry at or around children. On the contrary, children need to learn that one can be angry and discharge tension and be heard, in safety. Elizabeth Kubler Ross says that real anger lasts 20 seconds and is mostly noise. The problem comes when the positive messages (‘You are great’, ‘We love you’, ‘We’ll look after you’) are not equally strong or reliable. Often, although we feel these, we do not communicate them.

Almost every child is dearly loved, but many children do not know this fact; many adults will go to their death still believing that they were a nuisance and a disappointment to their parents. It is one of the most moving moments in family therapy to be able to clear away this mis-understanding.

At the times when a child’s life goes shaky – when a new baby is brought home, when a marriage breaks up, when failure occurs at school, when there is no work for a hopeful teenager – it is important to give positive messages, anchored with a hand on a shoulder and a clear look in the eye: whatever happens, you are special and important to us. We know you’re great.

So far we’ve talked about the unconscious programming of children to be unhappy adults. There are lots of direct ways too!

WHAT NOT TO DO

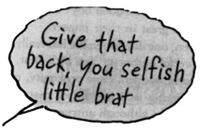

When disciplining, use put-downs instead of simple demands.

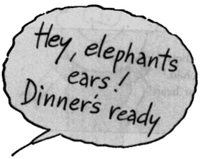

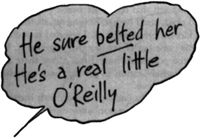

Use put-downs in a friendly way; say, as a pet-name.

Compare!

Set an example!

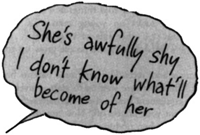

Talk to other people about children’s faults in their hearing.

Take pride in patterns that are bound to cause trouble later.

Use guilt to control children.

These sorts of statements can be left out of your parenting repertoire for good. You and they will feel better for it.

I’LL GIVE YOU CRAZY!

Have you ever listened to yourself talking to your kids, and just moaned? A lot of the things we say to kids are, well, crazy! Scots comedian Billy Connolly bemoaned some of these in a recent concert we heard…(you’ll have to imagine the accent).

‘Mum, can I go to the pictures?’ ‘Pictures! I’ll give you pictures.’

‘Can I have some bread then?’ ‘Bread! I’ll bread you my boy!’

Most of us can remember being told things as a child which simply made no sense at all, phrases like: pull your socks up young man…if you don’t come to your senses soon…you’ll smile on the other side of your face!…I’ll teach you to make a fool of me!…and so on. It’s no wonder some people grow up to be a little confused.

I was in a primary school recently where some parents had brought their toddlers to join a new play group. While we were waiting to start, a lively and curious little boy started to pull out some maths equipment from a shelf. His harassed-looking mum told him ‘If you touch that the teacher will cut your fingers off!’ Now any of us can understand the motivation to say this kind of thing – when nothing else works, try terror! But with this kind of message coming thick and fast, what can a child conclude about life? It can only go two ways: either the world is a crazy and dangerous place, or else, it’s no good listening to Mum, she talks a load of rubbish. Now there’s the start of a well adjusted life. We’ve all done it!

One day (true confession) I told my two-year-old son that the police might be cross with him if he didn’t wear his seatbelt. I was hot and tired, and I hate squirming my six-foot-four frame around inside cars to fasten seatbelt buckles on protesting kids. I resorted to a cheap trick, and I paid the price. As soon as the words came out of my mouth I regretted it. For days after I had questions thick and fast. ‘Do the policemen have guns?’, ‘Are there any policemen down this road?’ It was a major job of rehabilitation to get him back to feeling calm, and comfortable about the men and women in blue.

We shouldn’t have to explain everything to our kids, or endlessly reason with them till we are blue in the face. ‘Because I say so’ is a good enough reason some of the time. But there is nothing ever to be gained by needlessly scaring them. ‘When your father gets home…’ ‘You’ll make me so sick I’ll have to go away…’ ‘We’ll put you into a home…’ are the kinds of messages that harm and haunt even tough children. We are their main source of information early on, and later our credibility is put to the test (since they have or will have other sources to compare us with). Our job is to give them a realistic, even slightly rosy picture of the world – which they can build on as they go, and so become hardy and secure on the inside. When they encounter trickiness or dishonesty later in life, they will at least know that this isn’t completely the way of the world, that some people are trustworthy, and safe to be around – Mum and Dad included.

Why do parents put children down?

At this point, you could be feeling guilty about the way that you speak to your own children. Please don’t get these ideas out of perspective. There is a lot that can be done to overcome old programming whether your children are still little or even if they are now adults.

The first step is to begin understanding yourself, to know why put-downs became part of your parenting in the first place. Almost every parent is guilty of unnecessary put-downs from time to time. There are three main reasons for this.

1. You say what was said to you!

You weren’t taught about parenting in school: you had to start from scratch when your children were born and work it out for yourself. But you did have one clear example to work from – your own parents.

I’m sure you’ve found yourself in a heated moment yelling out and then thinking, ‘Good grief, that’s what my parents used to say to me and I hated it!’ Those old tape recordings are your ‘automatic pilot’, however, and it takes presence of mind and practice to react in ways you really prefer.

Some parents, of course, go to the other extreme. With painful memories of the way in which they were raised, they swear never to scold, hit or deprive their own children. The danger here is that they may overdo it, and their children suffer from a lack of control. It isn’t easy, is it?

2. You just thought it was the right thing to do!

It was once thought that kids were basically bad, and the thing to do was to tell them how bad they were. This would shame them into being better!

Perhaps you were brought up in this way. As a parent you simply hadn’t thought about self-esteem or the need to help children gain confidence. If so, I hope that what you are reading has changed your mind. Now that you realise how put-downs damage children, I’m sure you’ll be keen to stop using them.

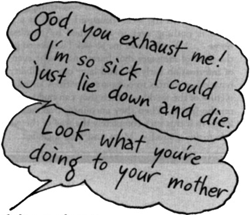

When money is short, or you are overworked, lonely or bored, or because being at home isn’t enough for you, then you are much more likely to be destructive in what you say to kids.

3. You are down on your own reserves

The reasons for this are clear. When we are pressured in any way we build up a body tension which needs discharging. It actually does feel good to lash out at someone, in words or actions.

Children suffer because they are easier to get angry with than your spouse, boss, landlord, or whomever. It’s important to think it through: I feel so tense! Who am I really angry with?

The relief of lashing out is short-lived since the child is likely to behave even more badly as a result but at the time it feels like a release.

If this happens, it is vitally important that you find a safe way to let off steam.

Tension can be dissipated in two ways:

1) by vigorous action, such as hitting a mattress, doing some vigorous work, going for a brisk walk. This is no small matter – many a child’s life has been saved by being shut in its bedroom while a distraught parent walks for miles as a means of calming down;

2) by dissolving the tension through talking with a friend, finding affection from a partner (if you’re fortunate enough to have one) or through some activity such as yoga, sport or massage that releases tension out of your body.

Eventually, as a parent, you must learn to care for yourself as much as for your children. You actually do more for your kids by spending some time each day on your own (your health, your relaxation) than by being totally devoted to serving them.

So, that’s the end of the bad news. The rest of this book is about how to do it the easier way! It is possible to change, and many parents have told me that just hearing about these ideas at a meeting or on the radio has helped them immediately.

Already while you’ve been reading, your ideas have been changing. You’ll find that, without even trying, your behaviour with your children will start to be easier and more positive. I promise!

THE WAY YOU SAY IT – POSITIVE WORDING MAKES COMPETENT KIDS

It’s not only praise or put-downs that determine a child’s level of confidence. There are some other important ways we program our kids – particularly by the way we give instructions and commands – in a negative or positive choice of words.

As adults, we guide our own behaviour and feelings by ‘self-talk’, the chatter that goes on inside our heads. (‘Better not forget to get petrol’, ‘Oh geez I forgot my purse, I must be getting senile’ etc.) Psychologists are amazed at the differences between how healthy, happy people, and unwell or distressed people, talk to themselves mentally. Self-talk is learned directly from your parents or teachers. With your own kids then, it’s a great chance to put in all sorts of positive and useful data, which your child can internalise – a comfortable and encouraging part of themselves for life.

Children learn how to guide and organise themselves internally, from the way we guide and organise them with our words, so it pays to be positive. For example, we can say to a child, ‘For goodness sake don’t get into any fights at school today!’ or we can say ‘I want you to have a good time at school and only play with the kids you like’.

Why should such a small thing make a difference? It’s all in the way the human mind works. If someone offered you a million dollars not to think of a blue monkey for two minutes – you wouldn’t be able to do it (try it now if you don’t believe us!). If a child is told ‘Don’t fall out of the tree’, then they have to think two things: ‘Don’t’ and ‘fall out of the tree’. Because we used those words, they automatically create this picture. What we think, we automatically rehearse. (Imagine biting hard into a lemon, and notice how you react just to the fantasy!) A child who is vividly imagining falling out of a tree is much more likely to do so. Far better to use positive wording: ‘Hold on to the tree carefully’, ‘Keep your mind on what you’re doing’.

There are dozens of chances each day to get this right. Rather than say ‘Don’t run out into the traffic’, it’s easier and better to say ‘Stay on the footpath close to me’ – so that the child imagines what to do, and not what not to do.

Give kids clear instructions as to the right way to do things. Kids don’t always know how to be safe, so make your commands specific: ‘Tracey, hold on firmly to the side of the boat with both your hands’ is much more powerful than ‘Don’t you dare fall out’ or worse still ‘How do you think I’ll feel if you drown?’ The changes are small but the difference is obvious.

Of course, learning to talk like this doesn’t occur by waving a magic wand. You will still need to back yourself up with action. By using positive wording, you will be helping your kids to think and act positively, and to feel capable in a wide tange of situations, because they know what to do, and aren’t scaring themselves about what not to do.

SPECIAL DISCOVERY – NEW VITAMINS CHILDREN NEED

We all know about the vitamins A to K, which we need in our daily diet to thrive and grow. It is rumoured that scientists have recently discovered some more vitamins which are just as essential. Here they are:

VITAMIN M – for music. Naturally occurring in young parents, can be added to family’s diet immediately. Put on great music and dance with the kids in your living room – often. Pick them up if they are too small, and dance around with them. Sing in the car, collect favourite tapes. Have some simple instruments around. If you take your kids to music lessons, make sure they are satisfying, or at least good fun, for your child.

VITAMIN P – for poetry. Teach little chants and rhymes to toddlers. Older kids can recite and perform favourite short poems at family gatherings. Listen to stories and poetry on tape to enjoy the spoken voice.

VITAMIN N – for nature. Make chances for your children to experience total non-human environments. For little kids, a back yard will do – lots of wild insects and crawlies, bird-attracting shrubs and trees. But whenever you can, get into the bush, and go to the beach. Watch sunsets. Camp out. Closely related to Vitamin S for spirituality, sometimes available at churches, temples, mosques and similar.

VITAMIN F – for fun. Available anywhere. Rubs off from children onto adults, and back again. Most common vitamin in the universe. Not naturally present in the workplace, but can be smuggled in.

VITAMIN H – for hope. Hope is naturally occurring. You just have to make sure it isn’t removed by exposure to toxins. Avoid watching the news or viewing the world through newspapers. Don’t indulge in gloom-mongering around kids – especially teenagers. Join something that makes a difference – Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth, WWW – whose publications are incredibly positive. Research has shown that kids with even slightly activist parents are more mentally healthy, have a more positive view of the world and the future, and do more about it.

2 What children really want

It’s cheaper than video games, and healthier than ice-cream!

The question that is uppermost in the minds of millions of parents can be summed up in one word..

Why do kids play up? Why do they always explore where they shouldn’t, do things that are not allowed, fight, tease, disobey, provoke, argue, make a mess, and generally seem to want to persecute Mum and Dad?

Why do some kids actually seem to enjoy getting into trouble?

This chapter tells you what is going on inside ‘naughty’ children, and how ‘bad’ behaviour is actually the result of good (healthy) forces going astray.

After reading this chapter, you’ll be able not only to see sense in children’s misbehaviour but you’ll also be able to act to prevent and convert it, making yourself and your children much happier.

You don’t believe me, do you? Read on!

Children play up for one reason only: they have unmet needs. ‘But what needs,’ you are thinking, ‘do my children have that are unmet? I feed them, clothe them, buy them toys, keep them warm and clean…’

Well, there are some extra needs (luckily very cheap to provide) which go beyond the ‘basics’ mentioned. These mysterious needs are essential, not only to make happy children but to maintain life itself. Perhaps I can explain best by telling a story.

In 1945, the Second World War ended and Europe lay in ruins. Among the many human problems to be tackled was that of caring for the thousands of orphans whose parents had either been killed or permanently separated from them by the war.

The Swiss, who had managed to stay out of the war itself, sent their health workers out to begin tackling some of these problems; one man, a doctor, was given the job of researching how to best care for the orphan babies.

He travelled about Europe and visited many kinds of orphan-care situations, to see what was the most successful type of care. He saw many extremes. In some places, American field hospitals had been set up and the babies were snug in stainless steel cots, in hygienic wards, getting their four-hourly feeds of special milk formula from crisply uniformed nurses.

At the other end of the scale, in remote mountain villages, a truck had simply pulled up, the driver had asked, ‘Can you look after these babies?’ and left half-a-dozen crying infants in the care of the villagers. Here, surrounded by kids, dogs, goats, in the arms of the village women, the babies took their chances on goat’s milk and the communal stewpot.

The Swiss doctor had a simple way of comparing the different forms of care. No need even to weigh the babies, far less measure co-ordination or look for smiling and eye contact. In those days of influenza and dysentery, he used the simplest of all statistics – the death rate.

And what he discovered was rather a surprise…as epidemics raged through Europe and many people were dying, the children in the rough villages were thriving better than their scientifically-cared-for counterparts in the hospitals!

The doctor had discovered something that old wives had known for a long time but no one had really listened. He had discovered that babies need love to live.

The infants in the field hospital had everything but affection and stimulation. The babies in the villages had more hugs, bounces and things to see than they knew what to do with and, given reasonable basic care, were thriving.

Of course, the doctor didn’t use the word ‘love’ (words like that upset scientists) but he spelt it out clearly enough. What was important, he said, was:

• skin-to-skin contact frequently, and from two or three special people;

• movement of a gentle but robust kind, such as carrying around, bouncing on a knee, and so on

• eye contact, smiling, and a colourful, lively environment; sounds such as singing, talking, goo-gooing, and so on.

It was an important discovery, and the first time that it had been stated in writing. Babies need human contact and affection (and not just to be fed, warmed and cleaned). If they are not given this, they may easily die.

So much for babies. But what about older children?

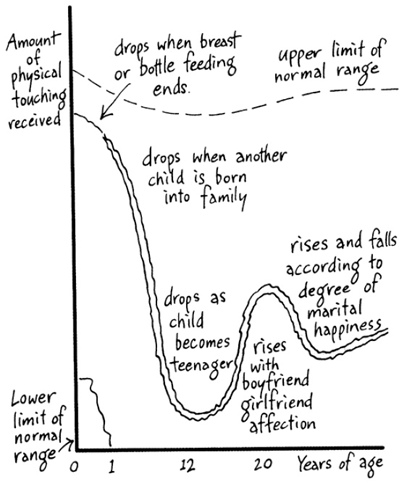

Here is an interesting thing – on page 32 is a graph of my estimate of the amount of touching (that’s right, physical touching) that people receive as their lives unfold.

Remember, this is the average situation. Who knows what is the ideal – perhaps a line straight across. You may be wondering about the dip at about two to three years of age. That’s when child number two (or three or four) usually comes along and affection has to be shared – a rough time for everyone!

Little babies like to be touched and cuddled. So do small children, although they are choosier about who does the cuddling. Teenagers often get awkward about it, but will admit in trust that they like affection as much as anyone. And, of course, by late teens they are pursuing specialised forms of affection with great energy!

I once asked an audience of about 60 adults to close their eyes and raise their hands if they got less affection than they would like to get in daily life. It was unanimous – every hand went up. After a minute the peeping began and the room began to ring with laughter. From this careful scientific study, I conclude that adults need affection, too.

Apart from physical touch, we find other ways to get good feelings from people. The most obvious one is by using words.

We need to be recognised, noticed and, preferably, given sincere praise. We want to be included in conversations, have our ideas listened to and even admired.

A three-year-old says it out straight: ‘Hey, look at me.’

Many rich people take little pleasure in their bank balance unless it can be displayed and someone is there to notice.

I am sometimes reduced to stitches by the realisation that most of the adult world is made up of three-year-olds running about shouting, ‘Look at me, Daddy’, ‘Watch me, you guys’. Not me, of course – I give lectures and write books out of mature adult concern.

So, an interesting picture emerges. We take care of our children’s bodily needs but, if this is all we do, they still miss out. They have psychological needs, too, and these are simple but essential. A child needs stimulation, of a human kind. He must have a diet of talking each day, with some affection and praise added in, in order to be happy. If this is given fully, and not begrudgingly from behind a pile of ironing or a newspaper, then it will not even take very long!

Many people reading this will already have older children, or teenagers. You may be thinking, ‘But already they have learned some bad ways of getting attention. How can I deal with that?’

Here is another story.

‘Of mice and men’

A few years ago, psychologists went about in white coats and worked mostly with rats. (Nowadays they wear sports coats and work mostly with housewives – things are looking up!) The ‘rat psychologists’ were able to learn a lot about behaviour because they could do things with rats that they couldn’t do with children. Read on, and you’ll see what I mean.